One year after the onset of the coronavirus recession, the U.S. labor market is still a long way from its February 2020 employment levels, but saw important job gains last month. According to the latest Employment Situation Summary by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. economy in February added 379,000 nonfarm payroll jobs—the greatest month-over-month gain since October of last year.

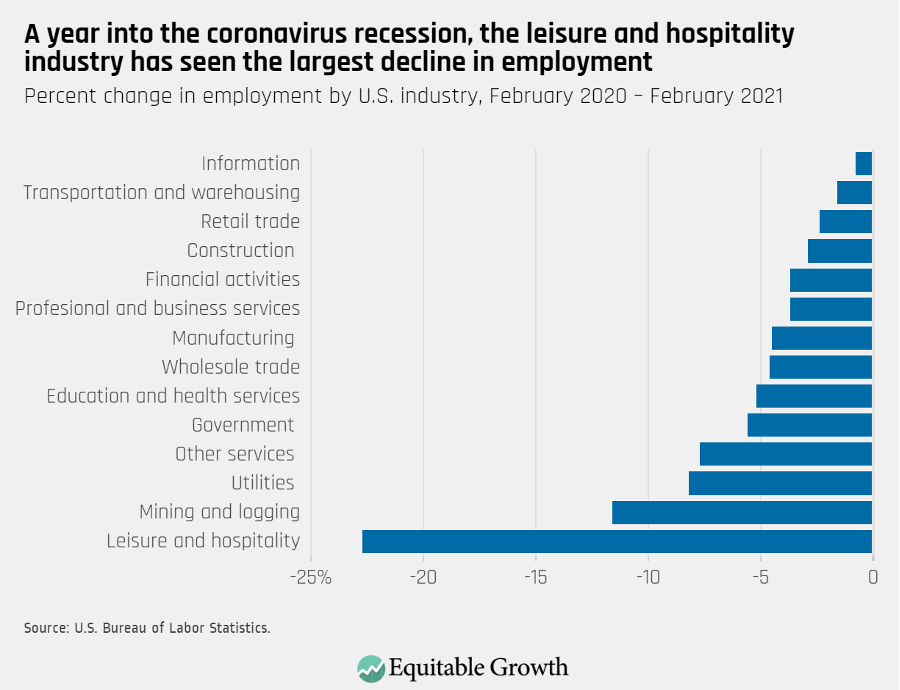

Today's release also shows that between mid-January and mid-February the overall unemployment rate fell from 6.3 to 6.2 percent, with 50,000 workers re-entering the U.S. labor force. Across sectors, last month's job gains were concentrated in leisure and hospitality, which added 355,000 jobs. Yet data on employment changes over the entire year show that the downturn remains especially hard for this sector and for service-providing industries in general. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

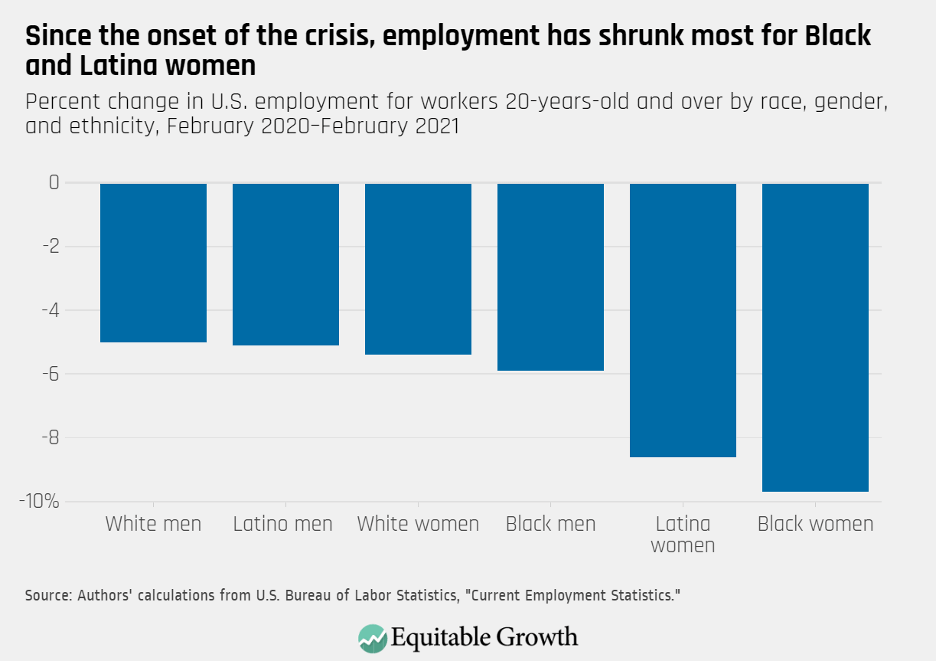

The economic pain brought on by the downturn continues to fall heaviest on some groups. The jobless rate stands at 9.9 percent for Black workers, at 8.5percent for Latinx workers, at 5.1 percent for Asian American workers, and at 5.6 percent for White workers. Disaggregating the data further shows that over the past 12 months, net job losses have been greatest for Black and Hispanic women and men—groups for whom employment declined by 9.7 percent and 8.6 percent, respectively. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Hispanic men's experience during the coronavirus recession

For Hispanic men, overall job losses are less severe than for women workers or Black men. Yet their experience during this recession also highlights important challenges they face in the labor market. For instance, Hispanic men are overrepresented in jobs that cannot be done from home. Despite accounting for about 8 percent of the U.S. workforce, these workers represent about a quarter of the construction workers and about 1 in 5 workers in the mining sector. In part as a result of their industry and occupational distribution, Hispanic men are facing risks associated with in-person work and have been more likely to experience joblessness than their White, non-Hispanic peers—a trend that risks entrenching longstanding inequities between the two groups of workers.

Consequently, as of the last quarter of 2020, Hispanic men were earning the lowest median weekly earnings of any other group of men, and just a bit higher than the weekly earnings than for Hispanic women.

Even though earnings disparities between Hispanic men and their White non-Hispanic peers are often attributed to differences in education, these pay disadvantages persist even among workers with the same level of education. A recent study shows that whereas 6 percent of White men with an advanced degree hold low-wage jobs, 13 percent of Hispanic men do. An analysis by the Economic Policy Institute shows that Hispanic men make about 15 percent less than White men who live in the same geographic region and have the same level of education and work experience. That gap, moreover, remains relatively unchanged since the early 1970s.

Researchers also find evidence that Hispanic men—and especially those who also are immigrants—are more likely to take low-wage and low-quality jobs, since they often lack the private networks and access to social insurance programs that would allow them to engage in longer job-search periods. Consistent with this evidence is that Latinx workers who are part of a labor union experience a particularly large pay boost. On average, workers covered by a union contract are paid 11 percent more than their nonunionized peers. Among Latinx workers, however, the wage premium associated with being represented by a union contract is more than 20 percent.

Yet research by Jake Rosenfeld of the University of Washington-St. Louis and Meredith Kleykamp at the University of Maryland, College Park also finds that Latinx immigrants are less likely to be part of a union than U.S.-born Latinx workers, suggesting that stronger networks and U.S. citizenship might protect workers against hostile responses to unionization efforts.

Conclusion

As the U.S. economy went into a pandemic-driven tailspin one year ago, almost 21 million workers lost their jobs between mid-March and mid-April alone. In February 2021, the U.S. labor market is short 9.5 million jobs relative to February 2020. These losses remain starkest for Black and Latina women, and other vulnerable groups of marginalized workers, highlighting the importance of policy in setting the groundwork for an equitable economic recovery.

Above all, policymakers should prioritize the enforcement of existing labor law. Even though this should be a priority for policymakers during booms as well as contractions, research shows that wage theft rises and falls with the business cycle—as recessions hit and the jobless rate rises, so does the share of workers who suffer a minimum wage violation.

Another way to tackle these U.S. labor market inequities is to lift the federal minimum wage, now frozen at $7.25 an hour for more than a decade. More than 40 percent of U.S. workers make less than $15 dollars per hour. In the food services industry, where Latinx workers make up more than a quarter of all workers, a whopping 78 percent of workers earn less than $15 dollars an hour. A large share of U.S. workers and an even larger share of women workers and workers of color would receive a much-needed pay boost should the federal minimum wage increase, helping drive a faster and more equitable economic recovery.