Every year, there is an issue that tends to dominate among the mainstream presentations. In previous years that has been the economics of rising inequality and last year it was the economics of climate change. Not surprisingly, this year it was the economic impact of COVID-19 and what policies to deal with the pandemic slump.

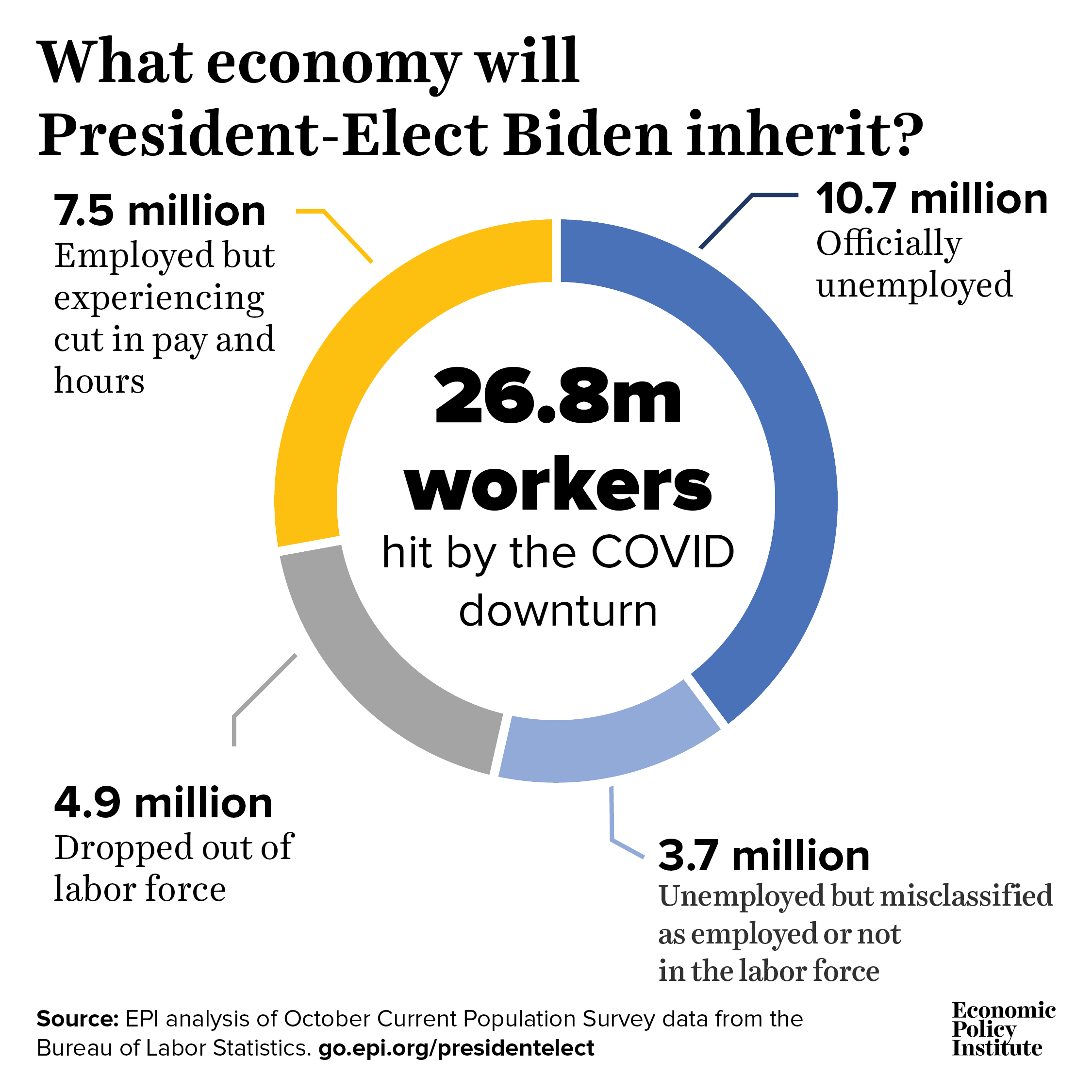

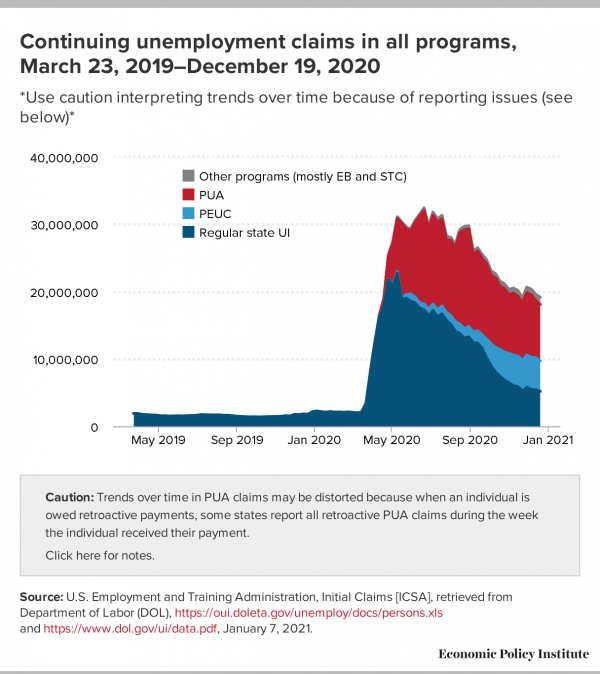

There were two large panel presentations on the economic impact. The first was on what was happening to the US economy and where it was going. Former central bank governor of India, Raghuram Rajan, now back at his neoclassical base at the University of Chicago, raised the risk of rising corporate debt turning into 'corporate distress'. He reckoned that the current monetary and fiscal support offered to small and large corporations "will have to end eventually" and "at that point, the true extent of the distress will emerge". Rajan reckoned it was time for 'targeted support' to reduce debt accumulation and so avoid future bad debts on the banking system – a banker's policy as recently advocated by the so-called Group of Thirty bankers.

Carmen Reinhart, recently appointed as chief economist of the World Bank andjoint author with Kenneth Rogoff of the huge (and controversial) book on the history of public debt, also echoed Rajan's worry about rising debt, not only among corporates in the US but particularly in the so-called emerging economies. In the Great Recession, the US dollar appreciated sharply against other currencies as it was seen as a 'safe haven' for cash and assets. But in this COVID-19 pandemic slump, the dollar has depreciated significantly because it seems investors fear that US fiscal spending is too large while dollar interest rates have plunged. But what happens to the ability of emerging economies to service their dollar debt, if the dollar should start to rise again?

Lawrence Summers, the guru of secular stagnation, reckoned that the pandemic slump has only increased the length of stagnation in advanced economies. Interest rates had dropped into negative territory and fiscal stimulus had been raised to new heights. But that would not end stagnation unless "there are structural policies adopted". He did not spell out what these were, but instead argued against untargeted fiscal spending like the proposed $2000 per person check to all Americans, which he saw as just adding to the incomes of those who had actually increased their incomes during the COVID. Summers has been attacked for his rejection of the $2000 payment from the left. But what it shows is that the mainstream is increasingly worried that fiscal and monetary stimulus is creating uncontrolled debt levels (despite low interest costs) that will have to be reined it at some point – and also that Federal Reserve largesse has mostly ended up in boosting the stock market and the better-off.

Liberal left economist and 'Nobel' laureate, Joseph Stiglitz called for a resetting of the US economy when the pandemic ends. He wanted to reverse the tax cuts to the corporations and better off implemented by Trump; increase environmental regulations; break the power of the tech monopolies and make productive public investments. What is the likelihood of any of this under the Biden administration over the next four years?

In contrast, right-wing orthodox John Taylor of Stanford University wanted the Fed to stop its emergency COVID bond purchases and other credit facilities as soon as possible, and for the new Biden administration to be cautious on more public spending. You see, for Taylor, the market system was innovative and works. During COVID, internet businesses and purchases had rocketed and this was the way forward, replacing the old ways with the new. But that needs not more regulation, but less regulation of businesses like Uber or Amazon.

Perhaps the most interesting paper in this session was that by Janice Eberly of NorthWestern University who showed that during the COVID slump, companies had saved huge amounts of capital spending on offices, travel and other physical equipment as staff worked from home (at their own expense). This provided an opportunity for business to boost the productivity of the workforce without extra capital spending and less labour – a way out for capitalism after the pandemic?

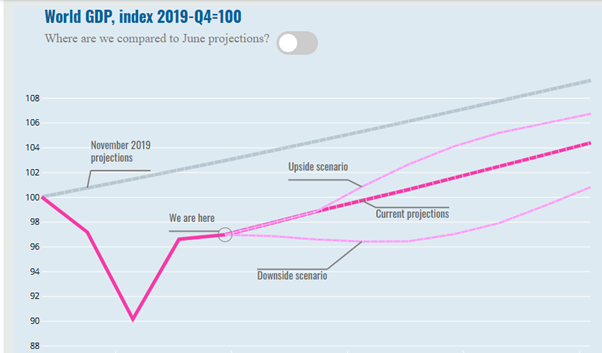

The second big session was on the world economy. By any measure, the panellists agreed that the COVID-19 slump was the worst in the history of capitalism. But even worse, it could take some time for economies to return to their pre-pandemic levels, if ever at all. On current projections, the OECD reckons that won't happen until 2022 and even then, world GDP will behind the pre-pandemic trajectory.

The impact on world trade has been even more damaging. According to the World Trade Organisation, world trade growth will never return to its previous trajectory.

And as it was argued in the US economic session, global debt levels are at record levels.

Dale Jorgenson of Harvard University is an expert on global productivity growthand its constituents. In his presentation, he reckoned that the differentials of growth in output and output per worker between the G7 economies and the 'emerging economies' of China and India would be resumed. "Growth in the advanced economies will recover from the financial and economic crisis of the past decade, but a longer-term trend toward slower economic growth will be re-established." Interestingly, he argued that the consensus view that China's economic growth will slow because its working-age population is falling may not be right, if China can raise the quality of its labour force through education and extend the working age. That could deliver an annual growth rate closer to 6% than the 4-5% forecast by many.

The other half of the Rogoff-Reinhart history of debt team, Kenneth Rogoff again presented his current view that the level of global debt is near a tipping point. Yes, interest rates are very low making debt servicing sustainable. But economic growth is also low and if interest costs (r) start to exceed growth (g), then a debt crisis could ensue. So the problem of fiscal sustainability has not gone away, as many argue. Of course, Rogoff only talks about public sector debt (graph), when the problem of record high corporate debt is much more worrying for the sustainability of future economic growth in capitalist economies.

Joseph Stiglitz's answer to a post-pandemic global debt crisis was to cancel the debts of the poorest countries. This should be done by "creating an international framework facilitating this in an orderly way". What chance of this being agreed and implemented by the IMF and World Bank, let alone all the private creditors like the banks and hedge funds?

My overall impression from these panels is that the mainstream is fairly pessimistic about a sufficient economic recovery from the pandemic, both in the US and globally. But the great and good are torn between the obvious requirement to maintain monetary and fiscal stimulus to avoid a meltdown in the world economy and financial assets; and the impending need to end that stimulus to avoid unsustainable debt levels and a new financial crisis. It's a dilemma for capitalist economics.

That dilemma also led to some papers by mainstream economists looking for ways to forecast future financial crashes. One paper reminded us that during the depth of Great Recession, the Queen of England visited the London School of Economics. As she was shown graphs emphasising the scale of imbalances in the financial system, she asked a simple question: "Why didn't anybody notice?" It took several months before she got an official reply from the economists. They blamed the lack of foresight of the crisis on the "psychology of denial". There was a "failure to foresee the timing, extent and severity of the crisis and to head it off." The causes of the Great Recession Now in this paper, the authors attempt to deal with this lack of foresight with machine learning. Using these modern techniques, they reckon that they can now predict systemic financial crises 12 quarters ahead. AnsweringTheQueen_MachineLearningAn_preview They go further in suggesting that the empirical work can offer 'precious hints' on why there are regular and recurring financial crises in modern economies – although I could not see what they were.

In another paper, the authors looked at five large financial crises over the last 200 years of capitalism to see what policies were most effective in recovering from crises.TwoHundredYearsOfRareDisasters_Fin_powerpoint They found that crises had "persistent effects both on financial markets and on economic activity". Surprise! However, they also found that since the end of the dollar-gold standard "downturns in economic activity following a crisis in the financial center continue to be quite protracted, the effects on financial markets are far less persistent." In other words, monetary injections by central banks under floating fiat currencies can preserve the value of financial assets but not help productive assets. Just as we have seen during the COVID slump.

The other worry about the impact of COVID for the mainstream was the possible collapse of trade and 'global value chains'. One paper found clearly that international trade wars and reducing the optimum distribution of international suppliers for political reasons was damaging. CuttingGlobalValueChainsToSafeguard_preview (1) It would reduce US GDP by 1.6% "but barely change U.S. exposure to a foreign shock".

The impact of COVID-19 was not the only issue that concentrated the minds of the mainstream. The economics of climate change was not ignored. Yet another paper showed that mainstream economics market solutions to global warming were failing. Carbon pricing was not working. Perhaps it is time to phase out mainstream economics itself. One paper raised the possibility that artificial intelligence could replace economists soon and do all the calculations that humans do now. WillArtificialIntelligenceReplaceCom_powerpoint

The next post will review the presentations by the radical wing of economics at ASSA 2021.