Good morning it's Wednesday!

And what a fine day to discuss an unfashionable leftist view of mine. The discussion "racial wealth gap" is a somewhat perverse way to think about the real issue: A relatively small minority of the American population controls a huge share of the wealth, and that small minority is disproportionately white.

You could, in principle, try to ameliorate the resulting racial wealth gap by making the wealthy elite more racially diverse — a strategy that would do nothing to help the vast majority of non-white people. Alternatively, you could try to narrow the gap between rich and non-rich people, which would help the majority of people of all races. The latter approach is better on both substance and politics. So much better that to an extent it raises the question of what's the point of talking about a "racial wealth gap" as opposed to simply a gap between the wealthy and the non-wealthy?

The wealth gap is about the wealthy

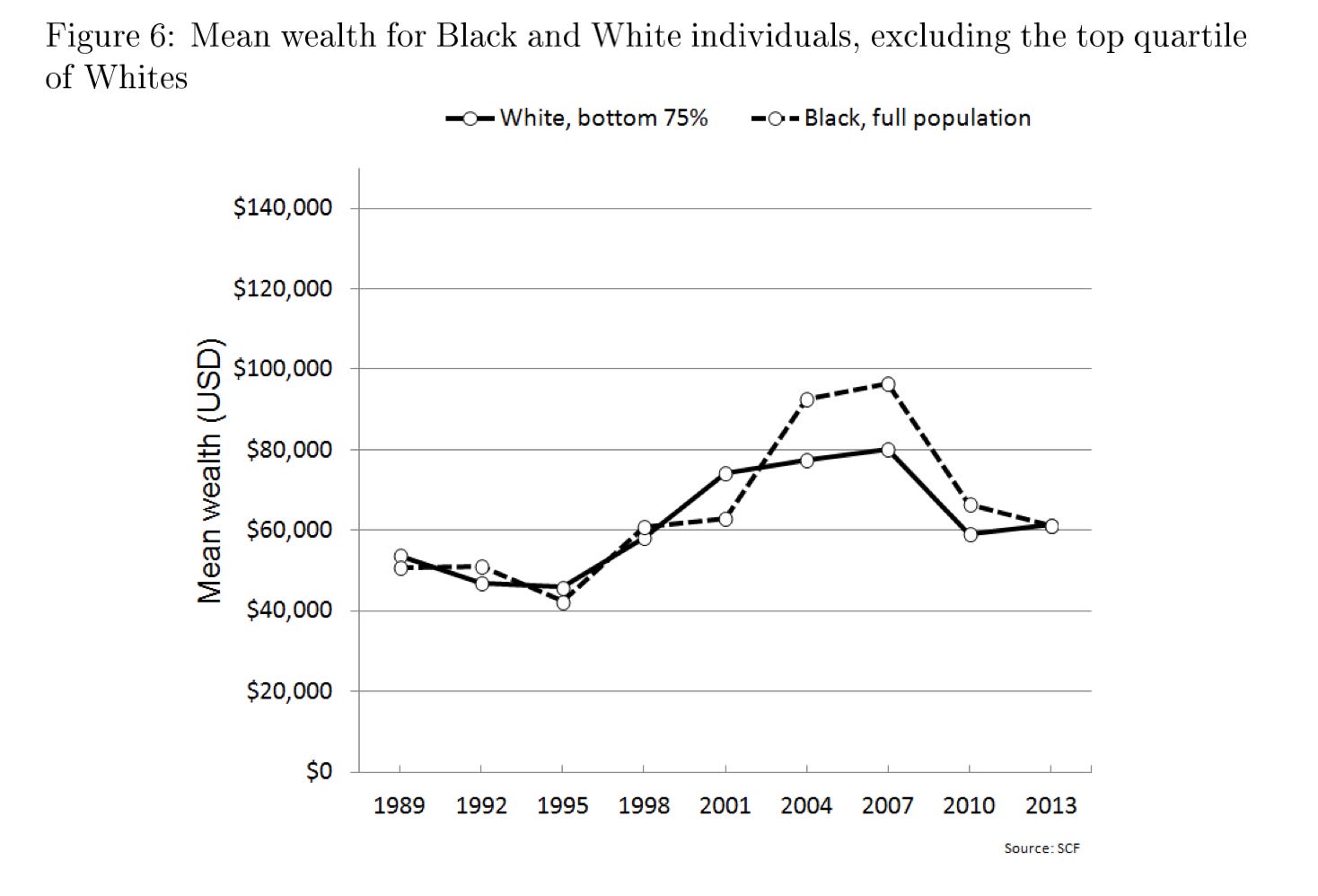

For his master's thesis, Kevin Carney took a detailed look at the evolution of the black/white wealth gap in the United States and among other things came away with this finding — if you lop off the richest quarter of white people, then suddenly Black and white wealth dynamics over time look very similar.

The infamous destruction of African-American wealth during the subprime mortgage crash, for example, also happened for the majority of white households. The reason the racial wealth gap grew during this period is that rich white people own a lot of shares of stock while everyone else's wealth is in their homes (if it exists at all).

Another way of looking at this is that while most white people are not members of the economic elite, the economic elite is a very white group of people.

With some help from Matt Bruenig of the People's Policy Project, I looked at the racial composition of the wealthy elite according to the Fed's Survey of Consumer Finances:

If you look at the top 10 percent of Americans by wealth, only 2.2 percent of those Americans are Black.

The top 5 percent of Americans by wealth are only 2 percent Black.

The top 1 percent, is only 0.5 percent Black.

Bruenig cautions that when you look at tiny subgroups like the top one percent, you get into sample size issues since the Fed only surveys about 5000 families (he also did an article looking at the numbers from the older SCF that's worth your time). But it's plain as day if you look at the numbers that as you go from top ten to top five to four, three, two, one you get a less and less Black group of people while the white percentage goes up and up.

Now some level that "white people are richer than Black people" and "the rich are a very white group of people" are two different ways of saying the same thing.

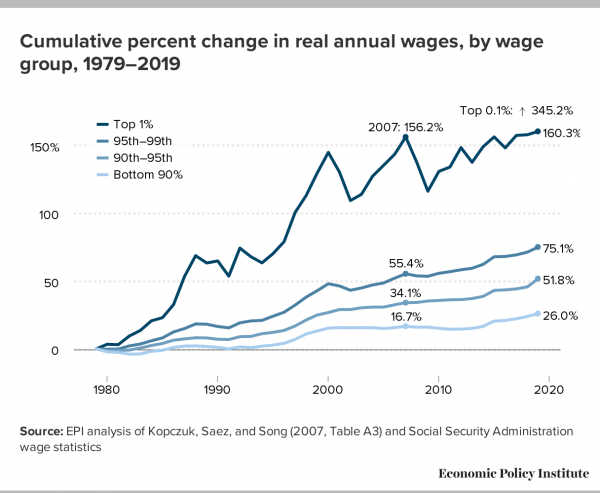

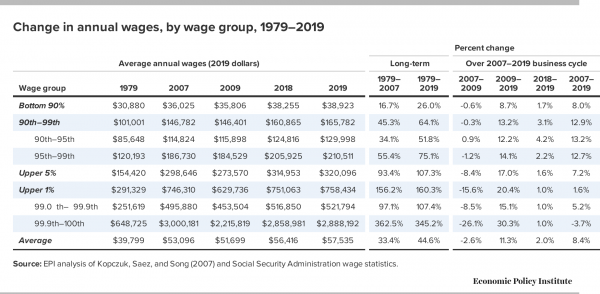

But I do think the framings lead to someone different ideas. Talking about income rather than wealth, Valerie Wilson and William Rogers found that the black/white economic gap grew between 1979 and 2016 primarily because wage inequality overall grew (see also this discussion in The Grio). You could address that either by trying to create a more egalitarian wage structure or by trying to create a more diverse set of people earning very high salaries even while doing nothing to improve the average person's pay. Similarly, you could approach the wealth gap issue primarily as a lack of diversity among America's billionaire class.

Billionaires own a lot of white wealth

Rich white guys. It's a thing.

According to the Forbes 400 list (an imperfect metric but good enough for a ballpark estimate†), there are seven African-American billionaires who have a combined wealth of $13 billion. These people are all very rich, obviously. But there's a (white) guy named David Tepper who's not particularly famous and who Forbes says is worth $13 billion all on his own. And he's only 41st on the list!

And billionaires collectively own a lot of wealth. Forbes says their top 400 are worth $3.2 trillion, of which less than one percent is owned by Black people. In a statistical sense, this drives a considerable racial wealth gap.

Now on the other hand, it's not as if the typical white person is a billionaire. Mark Zuckerberg's vast fortune is not materially benefiting Jared Golden's constituents in northern Maine or Joe Manchin's constituents in West Virginia via some magical property of shared whiteness.

Now a right-wing opponent of redistribution might want to do some racecraft to convince tens of millions of working class white people that they participate in the wealthy of white billionaires. But it's often been people on the left perpetuating this idea! Simply redistributing resources from billionaires to the majority of the population would help most white people, and help most Black people, and would also narrow the racial wealth gap.

Diversity or equality?

Going back to Carney's research, he's talking about the top 25 percent of the white wealth distribution, which is a much bigger group than just billionaires. But you do see among the mass affluent some of this same impulse to say we need more diversity, rather than more equality. Take for example the town of Hingham in the suburbs of Boston which is getting its own YIMBY group.

Except according to the Boston Globe "the Hingham YIMBY group is not focused on promoting low-income housing, but is instead aimed at increasing the town's racial diversity."

Now one point YIMBYs normally make about towns like Hingham is that by excluding new housebuilding and zoning out low-income families, they tend to render themselves very white. Hingham YIMBY's solution to this is to market the town more heavily to prosperous African-American suburbanites in Greater Boston and encourage them to consider moving to Hingham. And mathematically, they are correct. Hingham is not a large place, so a pure marketing campaign to convince more rich Black people to move there could make it a diverse place.

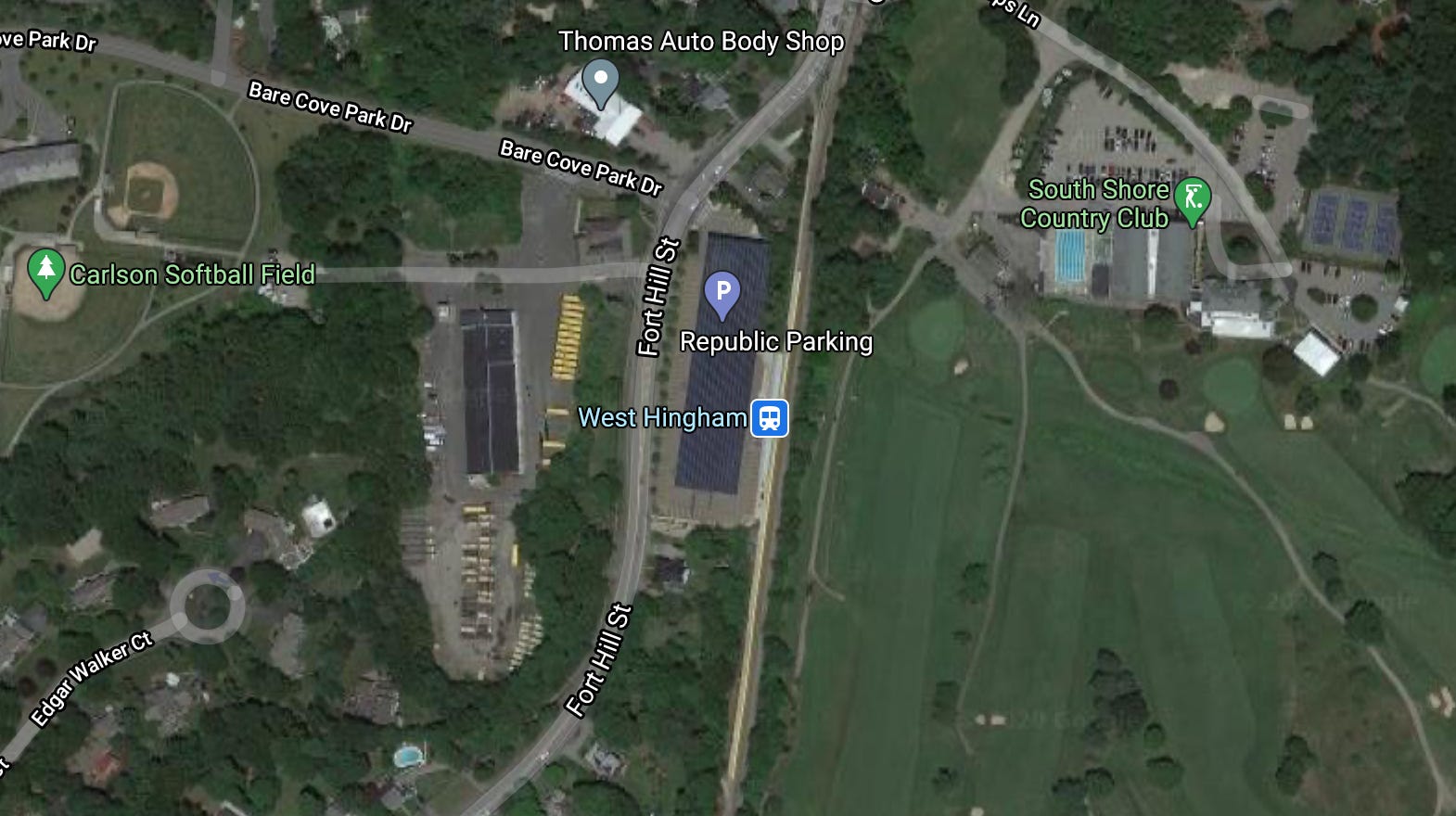

But look at this land-use in Hingham! The town is home to two MBTA commuter rail stations. One of them abuts a golf course and some underdeveloped land:

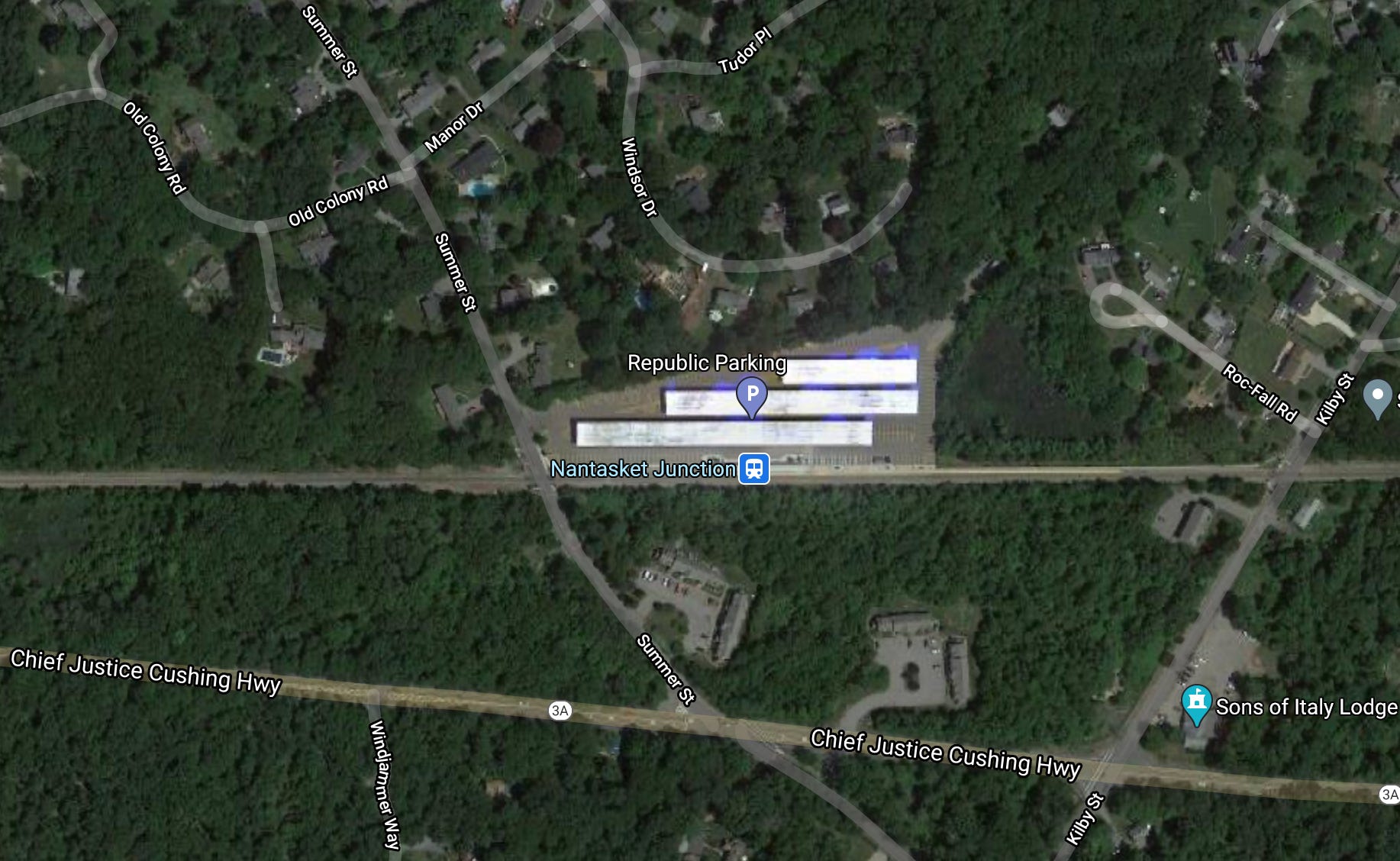

The other just abuts a bunch of underdeveloped land:

If you allowed the construction of apartment buildings near those stations, you'd almost certainly improve the diversity of the town. But more to the point, you'd create the opportunity for a bunch of people to live in transit-oriented housing with convenient commuter rail access to the Boston labor market. And if Massachusetts as a whole opted to legalize housing near transit, they could do an enormous amount to grow the state's economy, raise living standards, and promote sustainable commuting patterns.

Convincing a few affluent Black families to move to Hingham, by contrast, isn't really going to achieve much of anything.

And that's the big picture here. Exclusion is bad for racial equity. But that doesn't mean the solution is to fiddle with the racial equity dial by importing some really rich black people. The solution is for the Bay State to embrace housing growth and adopt international best practices in commuter rail operation. That would create broad prosperity that lifts up the majority of the people in the state and, yes, by doing so, it would also improve racial equity.

By the same token, you could take a Hingham approach to the billionaire problem and say that we need to make the billionaire class more diverse. But while conjuring up four dozen additional Black billionaires would have a impact on our understanding of Black wealth, it would not actually accomplish anything to make life better for the overwhelming majority of Black people. What would do that is the exact same thing as what would make life better for most white people — broad steps to create a less lopsided distribution of economic resources.

Tractable solutions are not "reductionism"

Now please do not read me as saying that there is no racism in America or that class politics is the only thing. We have lots of evidence of racial discrimination in the labor market, in the housing market, in policing and elsewhere.

But the way to tackle those problems would be to tackle them.

For example, there's solid reason to believe that the relatively straightforward step of conducting more DOJ "pattern or practice" investigations of police discrimination would lead to both less discrimination and fewer murders. And there's probably a lot the Civil Rights Division could be doing with audits to crack down on housing and labor market discrimination.

But if you're concerned about the economic disparity between white people and Black people, what you really ought to be concerned with is the disparity between rich people and non-rich people. You obviously don't want to narrow the gap in an economically destructive way. But if you can find growth-friendly ways to redistribute resources, you mechanically improve the racial gap. And even better, you have a tractable political problem — most voters are white, but most voters are not rich. And white people are overrepresented in the Senate, but rich people are underrepresented. So if you try to build a politics around racial redistribution, you're just going to lose. But if you try to build a politics around economic redistribution you just might win.

None of this is remotely revolutionary; it's just long-held conventional wisdom about politics. But the internal dynamics of progressive spaces have shifted in a weird way. Everyone is sensitive to often valid complaints that they've slighted racial justice in the past. But instead of dropping their work to refocus on problems that really are distinctively racial, what's mostly happened is either an effort to give redistributionist ideas new (but less popular) racial framing or else Hingham-esque efforts to achieve a superficial veneer of equity. But the majority of people in all ethnic groups are similarly situated in economic terms, and far and away the best way to make progress on material conditions is to emphasize that rather than reify the whiteness of the billionaire class.

† Thomas Piketty has told me that in his view the Forbes 400 (and similar lists from Bloomberg and other media sources) undercount the wealth of old money heirs who own diverse assets rather than large, easy to spot, stakes in single companies. If he's right about that, the true super-rich class is even whiter than what Forbes says.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image. Thanks to OpenTable for providing this restaurant data:

Thanks to OpenTable for providing this restaurant data: This data shows domestic box office for each week (red) and the maximum and minimum for the previous four years. Data is from BoxOfficeMojo through December 3rd.

This data shows domestic box office for each week (red) and the maximum and minimum for the previous four years. Data is from BoxOfficeMojo through December 3rd. This graph shows the seasonal pattern for the hotel occupancy rate using the four week average.

This graph shows the seasonal pattern for the hotel occupancy rate using the four week average.