|

| |||

|

| |||

The issue of college admissions is once again in the news. President Donald Trump's Justice Department has alleged that Yale University's use of race as a criterion for undergraduate admissions violates civil rights law. The accusation is sure to provoke lots of bitter ideological and partisan argument, and it will eventually have to be resolved by the courts.

But it also offers us an occasion to think carefully about the purpose of college admissions — what ought to determine who gets into top schools, and what actually does determine it. There's much that's unfair about the process, and the pandemic will only make that unfairness more acute.

Many people seem to assume it's fair for colleges to choose students based on abilities. But does society really gain from showering educational resources on those who are already good at school? And to the extent college is about networking, it seems counterproductive to have all the most capable people hang out and form friendships and marriages with all the other most capable people. Finally, there's no guarantee educational resources translate into workplace productivity; it's possible elite colleges funnel the nation's best and brightest toward occupations such as finance and consulting, where they add less value.

The argument for meritocracy in college admissions is that higher-ability people -- be they smarter, more driven, or whatever -- are better able to utilize the resources higher-ranked schools provide. Smart people may be more capable of handling the classes at Yale than the classes at Eastern Connecticut State University. In this view, a mismatch between the level of education and the level of student ability would simply lead to frustration, dropouts, and wasted resources.

So the question of who deserves to get into highly ranked colleges is a difficult one, and is unlikely to be resolved any time soon. But universities don't act for the good of society; they have their own selfish motivations. And one big motivation is money.

Universities get their funding from three main sources: government, tuition, and donations. Government funding has fallen since the turn of the century, with federal spending increasing slightly but state spending never fully recovering after the Great Recession. In general, universities get only a modest fraction of their total financial needs from the government; elite private schools such as Yale naturally get even less, as they're private.

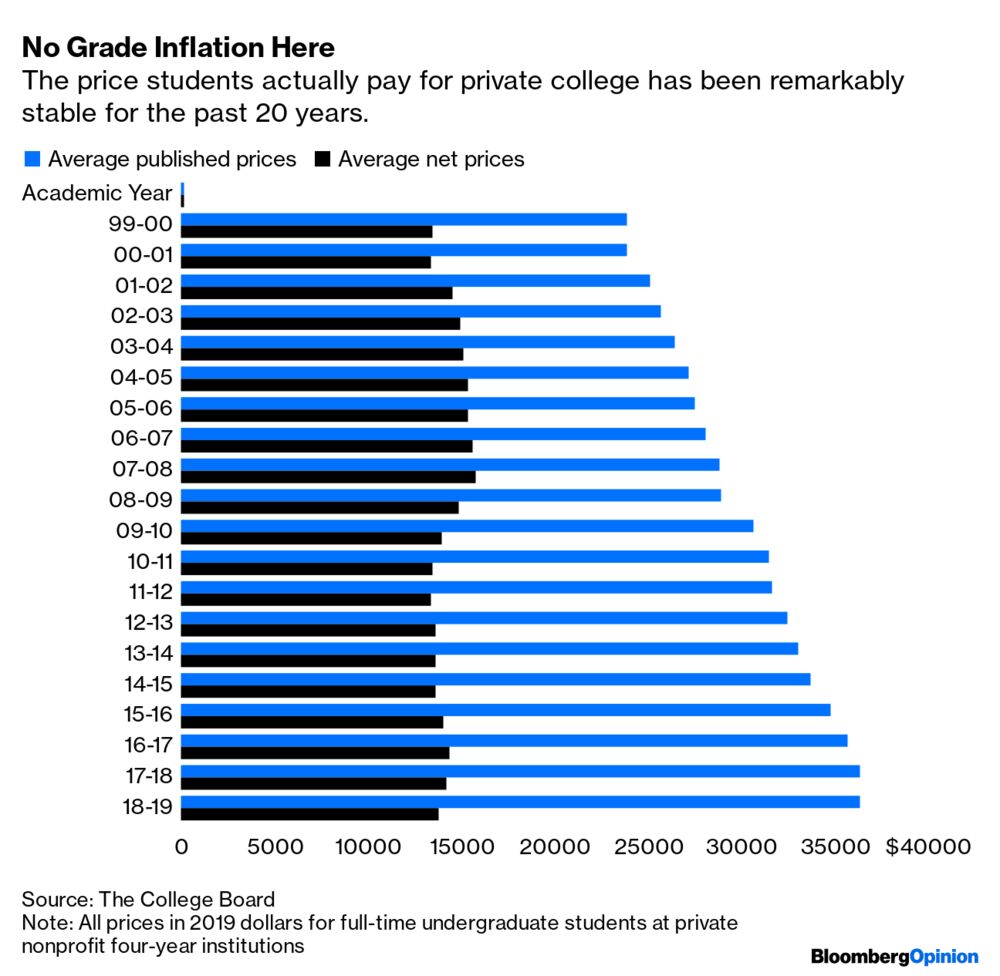

That leaves tuition and donations. College tuition has increased over the years, but not nearly as much as people think. For example, at private nonprofit institutions, which includes elite schools, net tuition — the price students actually pay — is about the same as it was at the turn of the century:

Instead of raising prices overall, these universities have raised the price they charge wealthy students, while using need-based financial aid to hold down the price paid by students of modest means.

But this gives universities an obvious incentive to admit more students from rich families. Under the need-based financial-aid system, a rich student is a profit center while a poor student represents a financial loss.

Donations have also become an important source of colleges' revenue, and more so for elite schools such as Yale. Alumni and philanthropic foundations (which are often controlled by alumni) are the two biggest sources of donations. As wealthier alumni are more likely to give bigger gifts, colleges have a financial incentive to admit the people they think will have the best chance of getting rich in the future.

So who's more likely to get rich — a smart kid from a modest background, or a rich kid of modest ability? Increasingly, the latter. A recent study by Georgetown's Center on Education and the Workforce found that kids from wealthy backgrounds with low test scores were far more likely to be well-off by early adulthood than kids from low-income families with high test scores. Intergenerational economic mobility has been falling in the U.S. for quite some time. All this means that for a university, picking tomorrow's rich alumni increasingly means picking today's rich parents.

Thus, while affirmative action opponents want universities to take high-ability students, and affirmative action supporters want universities to take underprivileged students, universities' actual financial incentive is to take neither of these, and instead to take students from wealthy families.

The easiest way to do this, of course, is legacy admissions; according to some sources, about one third of Harvard's incoming freshman class in 2019 were legacies. Certain sports that are mostly played by the wealthy, such as fencing and golf, are another way elite schools pick out rich kids.

Whatever your position on meritocracy vs. diversity, this seems like a clearly unfair outcome. The fair thing to do would be to ban legacy admissions and scale back admissions based on elite sports. But colleges have every economic incentive to keep betting on oligarchy.

Of course, colleges care about more than dollars — they care about their reputation and their moral mission to improve society. But with the pandemic squeezing every source of university funding, these institutions will have less leeway to pursue their higher calling.

Coronavirus will push colleges even more toward admitting the scions of wealthy families, at the expense of both the high-ability and the under-privileged. Barring a dramatic increase in federal government funding, it seems very likely college admissions will only become less fair in the years to come.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Noah Smith at nsmith150@bloomberg.net

We are really in an unprecedented period where the economy is trying to recover from the shutdowns of April and May, while being faced with partial shutdowns due to the resurgence of the pandemic in large parts of the country. We are struggling to make sense of data, which often has a substantial lag. We are still getting data from July even as we are in the last weeks of August. Furthermore, when we have large monthly changes, the picture at the end of July could have been very different than the beginning of the month.

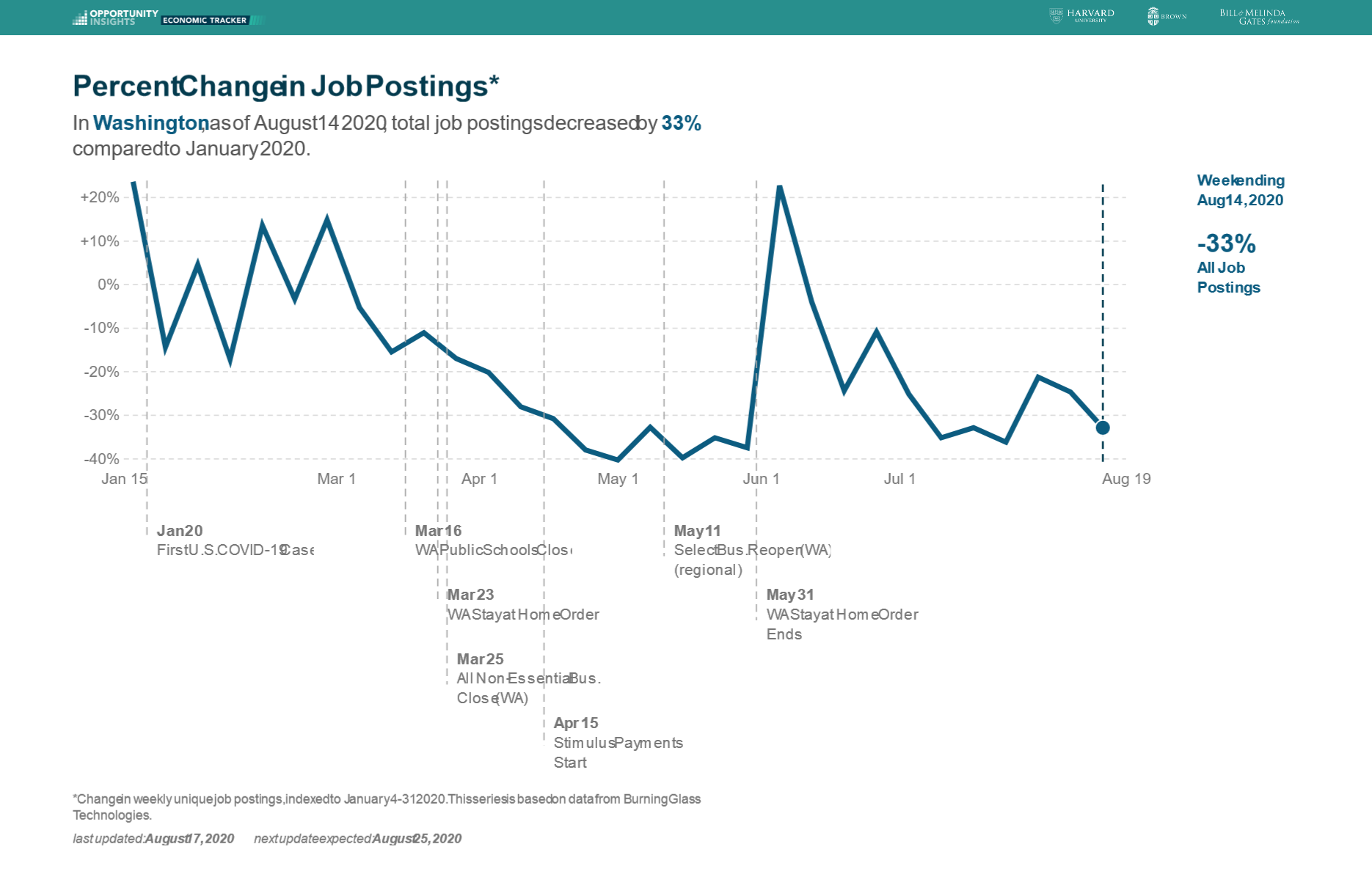

The Opportunity Insights program at Harvard University is trying to help navigate the storm with its Economic Tracker. This provides much more current data on a variety of measures by relying on various industry sources. The latest picture is not good.

Starting with the one I find most troubling, their source on job posting shows a huge falloff in August. Nationally, we are almost back to the lows reached in May.

There is the qualification that these are posting at small businesses, so perhaps the story would look different if we included and mid-sized and large businesses, but still this picture is not encouraging. Their data on small businesses that are open and revenue are also not good.

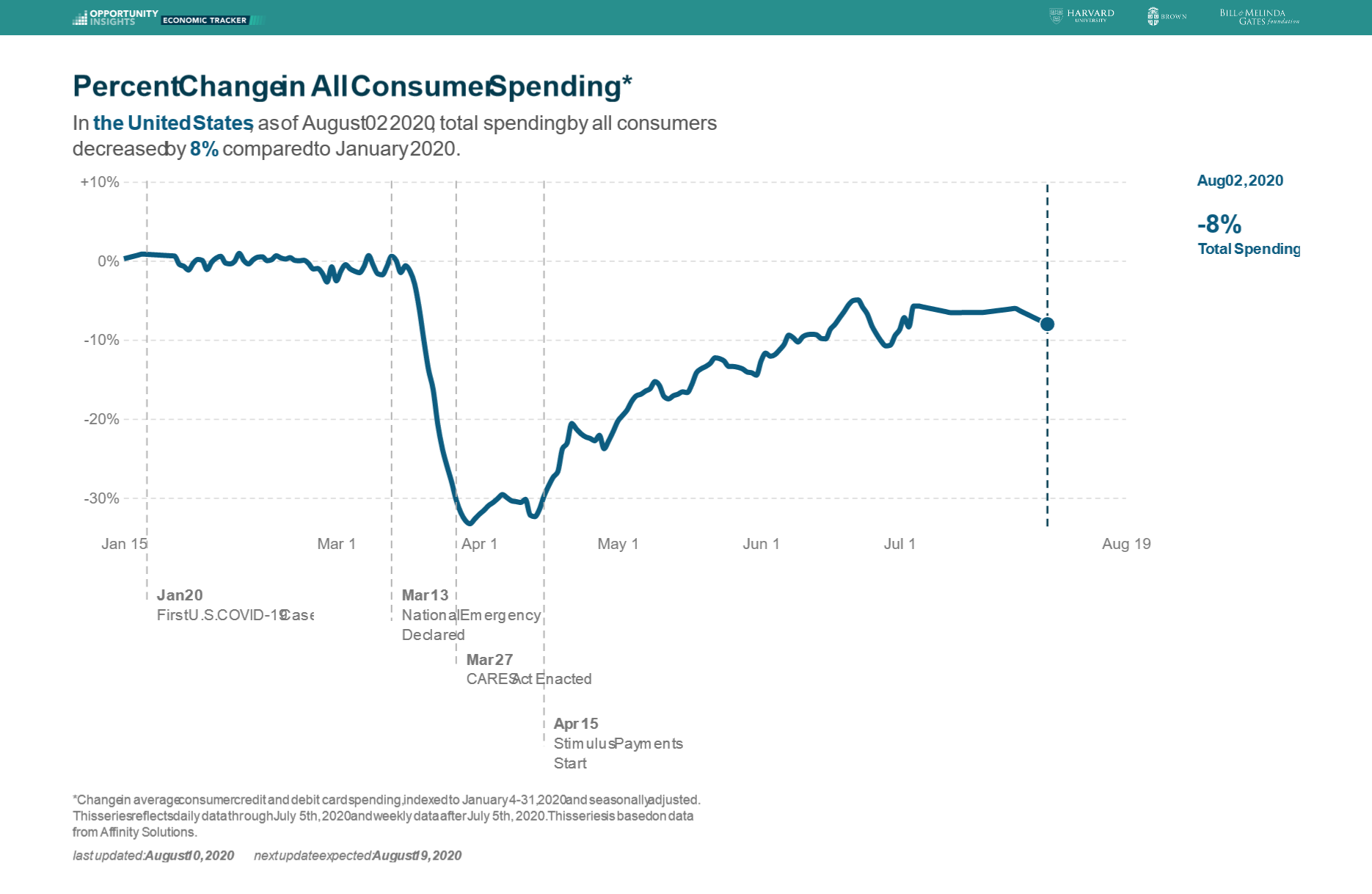

The other very disturbing item is their data on consumer spending, which is derived from credit and debit card spending.

The data show a healthy bounce back in June, but then spending levels off in July. Then, spending begins to trail off at the end of the month and start of August. Note that this is just as unemployment insurance supplements are ending.

These are new data sources that I and most other economists are not familiar with. That means that there can be quirks that explain the plunge in job postings and falloff in spending that we do know about. But on its face, these data suggest a recovery that is stalling, with many businesses closing and millions of workers not being able to go back to their jobs.

That should make the case for a new rescue package more urgent and also again remind us of the importance to the economy of bringing the pandemic under control.

Longstanding problems with the Unemployment Insurance system in the United States are immediately evident amid the coronavirus recession and echo the problems experienced during the Great Recession more than a decade ago. These include:

The current disarray in the Unemployment Insurance system is neither a surprise nor an accident. It is the result of decades of conscious choices made by policymakers at the state and federal levels: Over the past decade, many states limited Unemployment Insurance benefits, made accessing the program more difficult, and allocated insufficient funds for program administration. This results in chaos and uncertainty just when Unemployment Insurance is critical to prevent deterioration in the wider economy and save families from precarious financial situations.

As in the Great Recession, states' trust funds are now being depleted, which sets the stage for the erosion of benefit levels while the crisis remains ongoing. And, as was the case in the Great Recession, in the first months of the coronavirus crisis, policymakers have yet to remedy the issues at the heart of these administrative failures.

But it's not too late. Unemployment Insurance is a joint state-federal system. These programs are run at the state level but follow federal guidelines under the Social Security Act. Reforms to this system are important at both levels. The key resources below provide the details for enacting these reforms.

"Unemployment Insurance reform: A primer," by Til von Wachter

This primer summarizes how the Unemployment Insurance system functions in the United States and four ways it falls short. First, the current UI system suffers from financial instability that risks compromising its major role as a stabilizer in recessions. Second, the coverage of unemployment benefits has eroded over time, with a declining fraction of workers receiving lower benefits amounts. Third, the UI system does little to avert the large, long-lasting earnings losses among re-employed workers. And fourth, there are persistent questions about the effectiveness of Unemployment Insurance and related programs to quickly re-employ job losers. This primer lays out easy-to-implement small changes to address these problems, as well as fundamental changes to modernize the program.

"Unemployment Insurance and macroeconomic stabilization," by John Coglianese and Gabriel Chodorow-Reich

The authors lay out a plan for improving the Unemployment Insurance program's function as an anti-recessionary automatic stabilizer. They propose measures that increase take-up of regular unemployment benefits, full federal financing for extended benefits alongside improvements in the formula and design of extended benefits triggers, and an increase in the unemployment benefit amount when extended benefits are triggered.

"Fool me once: Investing in Unemployment Insurance systems to avoid the mistakes of the Great Recession during COVID-19," by Alix Gould-Werth

Gould-Werth presents a description of the problems in the Unemployment Insurance system exposed during the Great Recession and then repeated during the coronavirus crisis. She shows that policymakers have an opportunity to intervene and improve the functioning of the Unemployment Insurance system by increasing and indexing the federal taxable wage base, redesigning extensions to respond to economic changes quickly, and standardizing a minimum benefit level and duration that are sufficiently generous.

"Factsheet: Unemployment Insurance and why the effect of work disincentives is greatly overstated amid the coronavirus recession," by Equitable Growth

One of the biggest political obstacles to fixing the UI system is the fear that increasing access and generosity of benefits will discourage people from working. This Equitable Growth factsheet breaks down the research on work disincentives, showing that the amount of attention given to work disincentives (quite large) is disproportionate to the magnitude of the disincentives themselves, which are substantively small. At the same time, relatively little attention is paid to the benefits of Unemployment Insurance.

Evolution was the driving force of these changes. Suitability and adaptation was a key to competitive success. Life evolved so it could adapt to changing conditions. But every now and again, fate intervened, in the form of five mass extinctions.

The most recent: About 66 million years ago, a 7.5-mile-wide asteroid traveling about 50,000 mph slammed into the earth in the ocean near Chicxulub, Mexico. The collision resulted in an explosion estimated at over 100 trillion tons of TNT. That's about a billion times more energy than the Hiroshima atomic bomb. The impact gouged the Earth's crust several miles deep and more than 115 miles long.1

It was not a good day to be a dinosaur.

Everything within 1,000 miles was killed by a giant fireball. That was followed by a 1,000-foot high tsunami, extinguishing the fires, and drowning anything that survived. Just in case a few creatures were still standing, a 600-mile an hour wind blast tore through the region. And that was just day one. Nuclear winter followed, chilling the planet by a global average of 14 to 18 degrees.2

Eventually, the critters that could adapt to these circumstances did. Thus, the dinosaurs demise was soon followed by the rise of the mammals. And by soon, I mean 10s of millions of years.

What does any of this have to do with markets, economics and investing?

You might be surprised.

I am entranced by the concept of how externalities intervene in functioning systems. In markets, usual variables affect the normal secular cycles. The ebb and flow of the economy, inflation, consumer spending, employment, fiscal and monetary policy, sentiment, interest rates, etc. all impact the longer cycle of price and value.

What happens when an externality hits the markets like that asteroid from space? What happens when a non-economic event crashes into stocks and bonds, and derails their prior path? Consider some of history's externalities that have impacted markets:

• 1914 Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, sparking WW1;

• 1941 Attack on Pearl Harbor, bringing the US into WW2

• 1963 Assassination President JFK

• 2001 September 11 Terror Attacks on USA

• 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, leading to a full system failure at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear plant;

• 2020 Covid-19 Pandemic, leading to a global lockdown.

There are surely many more you can think of, but these six are the first ones that come to mind.

In each of these cases in the past, when externalities hit, markets would wobble. Often, they would create a spike in fear that led to a sell off, fast and hard. But then, the markets would normalize, and simply resume their prior trend.

That seems to be what is taking place currently: Covid 19 led to the fastest bear market in history, and the fastest snapback to prior highs. The move down was so deep that economically, none of the data could fit on the usual charts. I mentioned in April that we should not be too quick to assume the bull market was over, and so far, events seem to be confirming that view. Eventually, we will have a vaccine and a treatment for COVID.

Which leads to an interesting question:

When all this is over, will the FAANMG advantages stick? Or, will mean reversion occur, as the prior economic structures reassert themselves? Will the economic dinosaurs soon find themselves replaced by smarter, more adaptable mammals?

I don't pretend to know, but I do find these questions fascinating.

More on this next week.