https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-08-19/college-admissions-are-about-to-get-even-more-unfair

The issue of college admissions is once again in the news. President Donald Trump's Justice Department has alleged that Yale University's use of race as a criterion for undergraduate admissions violates civil rights law. The accusation is sure to provoke lots of bitter ideological and partisan argument, and it will eventually have to be resolved by the courts.

But it also offers us an occasion to think carefully about the purpose of college admissions — what ought to determine who gets into top schools, and what actually does determine it. There's much that's unfair about the process, and the pandemic will only make that unfairness more acute.

Many people seem to assume it's fair for colleges to choose students based on abilities. But does society really gain from showering educational resources on those who are already good at school? And to the extent college is about networking, it seems counterproductive to have all the most capable people hang out and form friendships and marriages with all the other most capable people. Finally, there's no guarantee educational resources translate into workplace productivity; it's possible elite colleges funnel the nation's best and brightest toward occupations such as finance and consulting, where they add less value.

The argument for meritocracy in college admissions is that higher-ability people -- be they smarter, more driven, or whatever -- are better able to utilize the resources higher-ranked schools provide. Smart people may be more capable of handling the classes at Yale than the classes at Eastern Connecticut State University. In this view, a mismatch between the level of education and the level of student ability would simply lead to frustration, dropouts, and wasted resources.

So the question of who deserves to get into highly ranked colleges is a difficult one, and is unlikely to be resolved any time soon. But universities don't act for the good of society; they have their own selfish motivations. And one big motivation is money.

Universities get their funding from three main sources: government, tuition, and donations. Government funding has fallen since the turn of the century, with federal spending increasing slightly but state spending never fully recovering after the Great Recession. In general, universities get only a modest fraction of their total financial needs from the government; elite private schools such as Yale naturally get even less, as they're private.

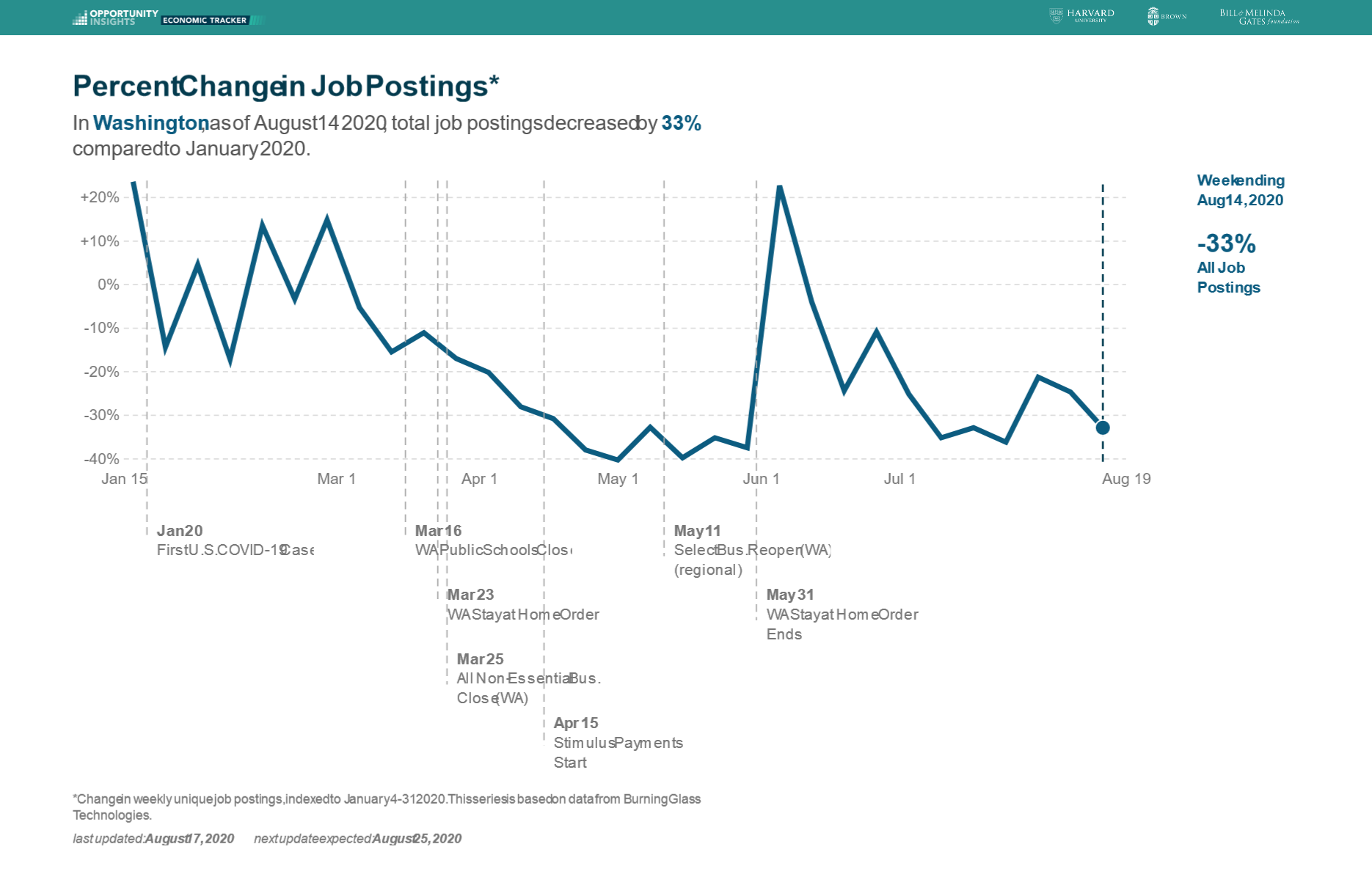

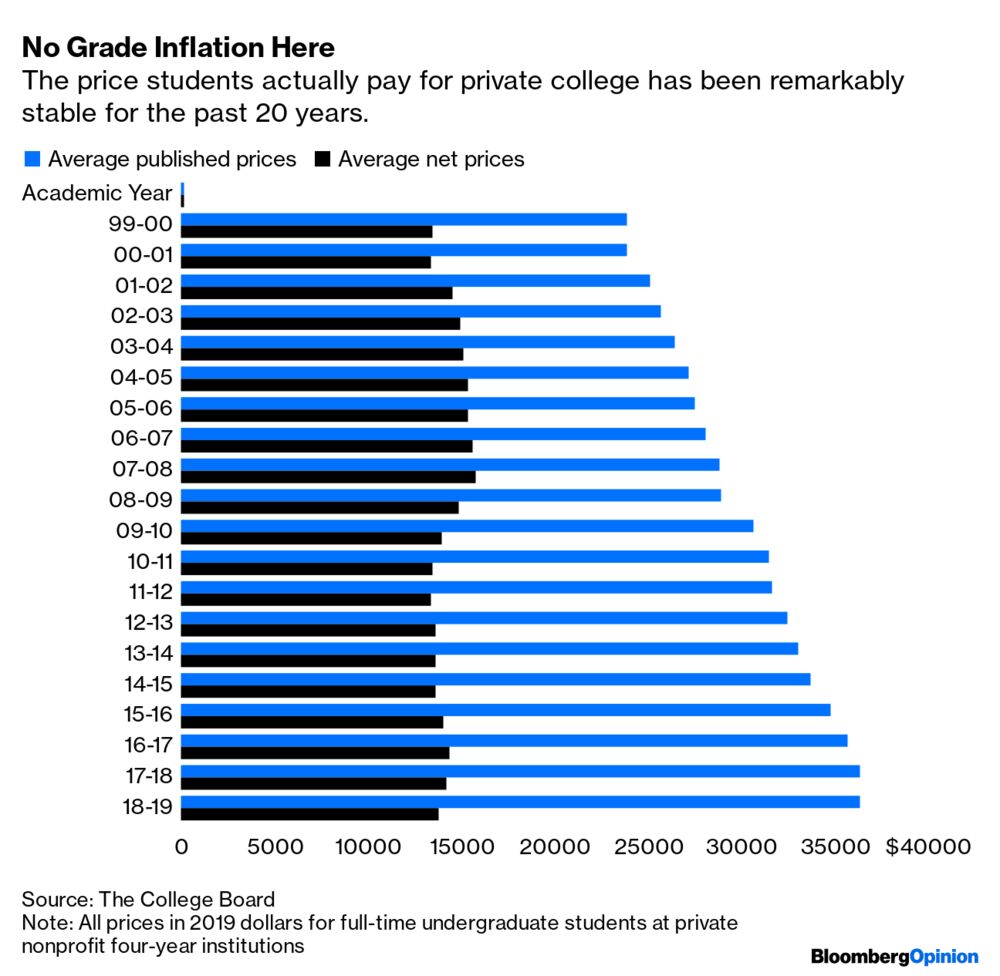

That leaves tuition and donations. College tuition has increased over the years, but not nearly as much as people think. For example, at private nonprofit institutions, which includes elite schools, net tuition — the price students actually pay — is about the same as it was at the turn of the century:

Instead of raising prices overall, these universities have raised the price they charge wealthy students, while using need-based financial aid to hold down the price paid by students of modest means.

But this gives universities an obvious incentive to admit more students from rich families. Under the need-based financial-aid system, a rich student is a profit center while a poor student represents a financial loss.

Donations have also become an important source of colleges' revenue, and more so for elite schools such as Yale. Alumni and philanthropic foundations (which are often controlled by alumni) are the two biggest sources of donations. As wealthier alumni are more likely to give bigger gifts, colleges have a financial incentive to admit the people they think will have the best chance of getting rich in the future.

So who's more likely to get rich — a smart kid from a modest background, or a rich kid of modest ability? Increasingly, the latter. A recent study by Georgetown's Center on Education and the Workforce found that kids from wealthy backgrounds with low test scores were far more likely to be well-off by early adulthood than kids from low-income families with high test scores. Intergenerational economic mobility has been falling in the U.S. for quite some time. All this means that for a university, picking tomorrow's rich alumni increasingly means picking today's rich parents.

Thus, while affirmative action opponents want universities to take high-ability students, and affirmative action supporters want universities to take underprivileged students, universities' actual financial incentive is to take neither of these, and instead to take students from wealthy families.

The easiest way to do this, of course, is legacy admissions; according to some sources, about one third of Harvard's incoming freshman class in 2019 were legacies. Certain sports that are mostly played by the wealthy, such as fencing and golf, are another way elite schools pick out rich kids.

Whatever your position on meritocracy vs. diversity, this seems like a clearly unfair outcome. The fair thing to do would be to ban legacy admissions and scale back admissions based on elite sports. But colleges have every economic incentive to keep betting on oligarchy.

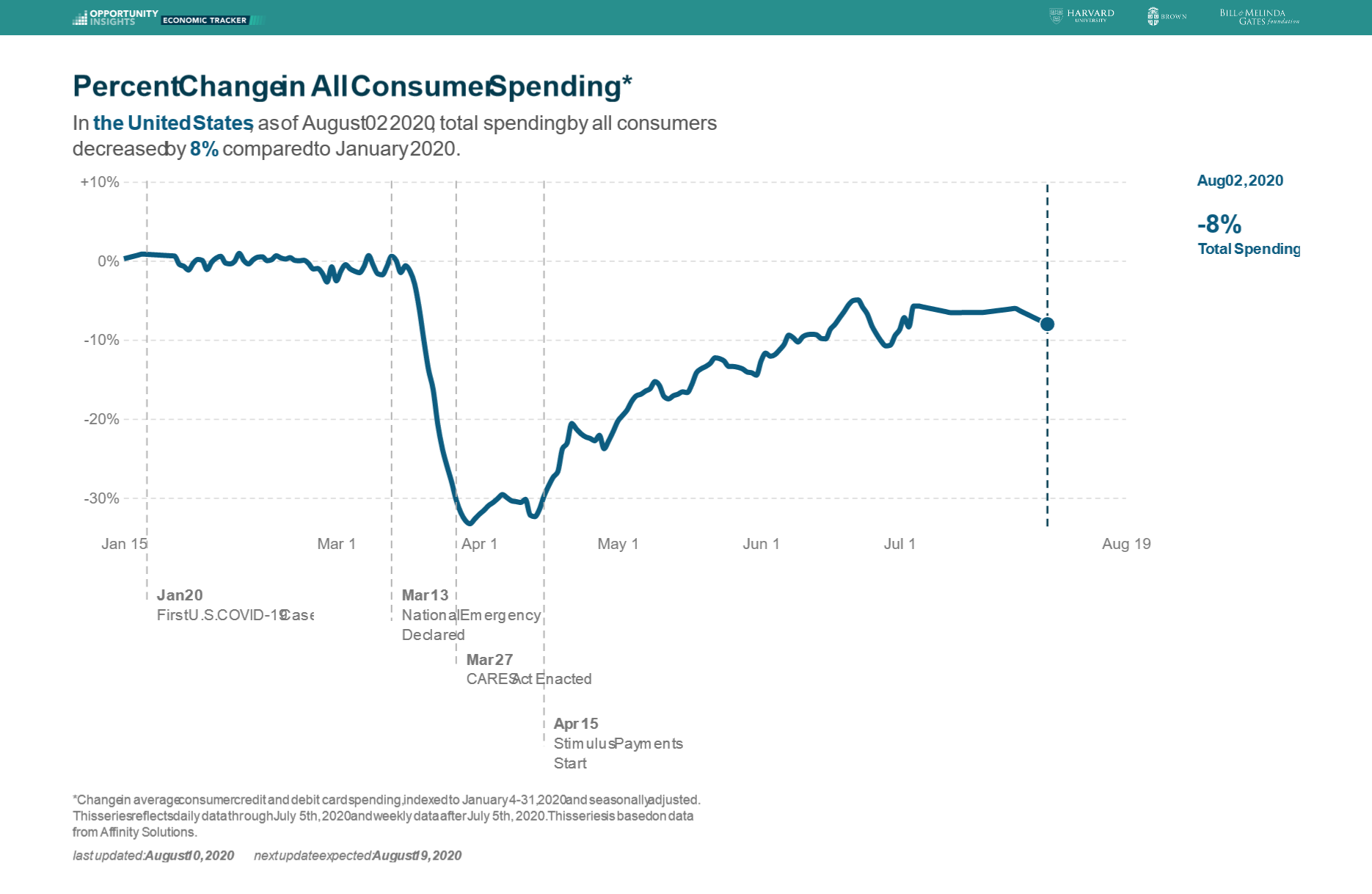

Of course, colleges care about more than dollars — they care about their reputation and their moral mission to improve society. But with the pandemic squeezing every source of university funding, these institutions will have less leeway to pursue their higher calling.

Coronavirus will push colleges even more toward admitting the scions of wealthy families, at the expense of both the high-ability and the under-privileged. Barring a dramatic increase in federal government funding, it seems very likely college admissions will only become less fair in the years to come.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

-- via my feedly newsfeed