https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/07/13/unemployment-payment-delays/?utm_source=feedly&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=wp_business

The automated phone system for the state's unemployment system takes her to a queue for a callback that has yet to come. Visits to state offices have been fruitless. While Herdez was finally able to get an appointment with someone at the unemployment agency to look at her case, it's not until August, she said.

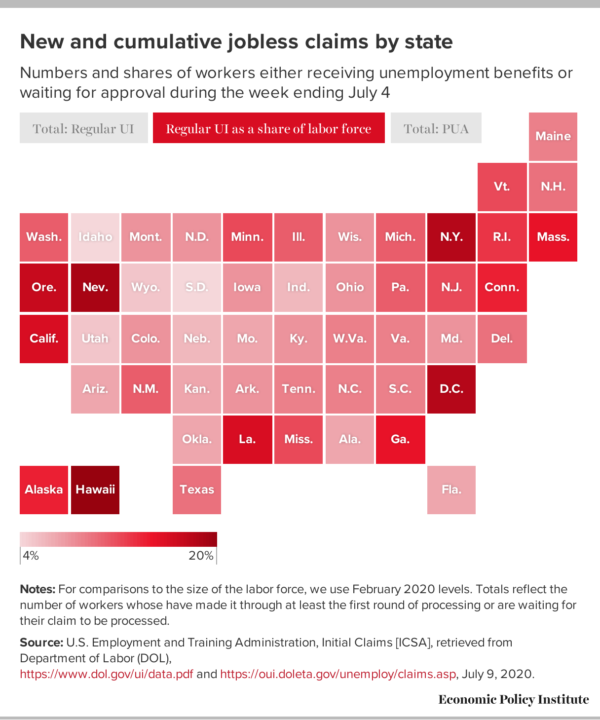

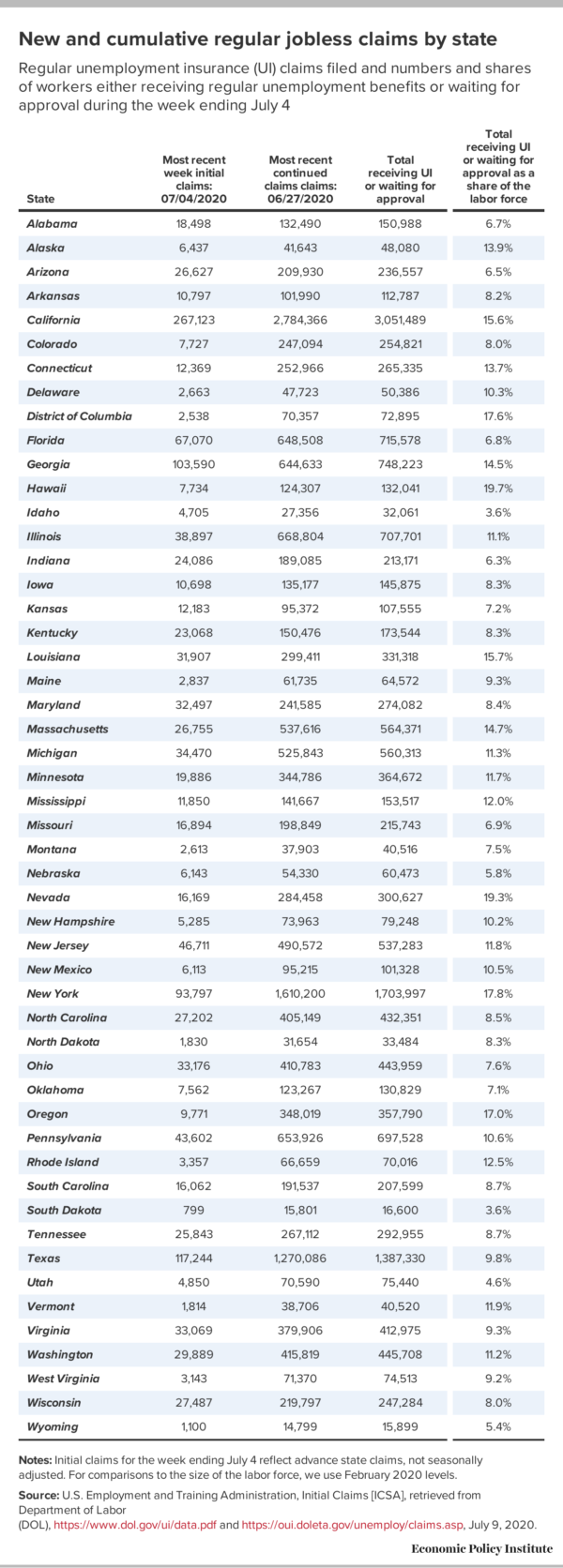

The pandemic's toll on workers who have been furloughed or laid off like Herdez is measured in numbers that splash across headlines: 1.4 million new weekly unemployment claims and 18 million people are already receiving continuous unemployment insurance. Tens of thousands of workers at Levi's, Wells Fargo and United Airlines learned this past week they could be furloughed or laid off in coming months, sending those workers to seek jobless benefits as well.

Four months into the worst recession since the Great Depression, tens of thousands of workers like Herdez across the country have filed for jobless claims but have yet to receive payments. Many are now in dire financial straits.

"We've been only able to make half payments on everything," Herdez said in an interview. "We bought a large amount of groceries and have been taking things out of the freezer, but as the weeks go by, it's hard to figure out whether to pay bills or whether we have enough food to last the week."

The issue has spilled back into public view in recent weeks, as thousands of frustrated workers awaiting payments have camped out, sometimes overnight, in front of unemployment offices in states like Oklahoma, Alabama and Kentucky.

The ongoing delays are the result of a confluence of crises, experts say.

A flood of new jobless applications — about 50 million — has overwhelmed state unemployment offices over the past four months. The agencies themselves are hampered by years of neglect. They rely on reduced staffs and badly outdated technology after years of budget cuts, often at the behest of business groups and Republican legislatures. Issues with fraud and user confusion over the new rules and filing process have further bogged down the process.

But cases like Herdez show what happens when workers simply run out of money and the social safety net malfunctions with defaulted payments and trips to food banks. In more desperate situations, workers become homeless.

"We've kind of abdicated our responsibility to the unemployed," George Wentworth, a senior counsel at the National Employment Law Project and an expert on unemployment insurance. "There need to be more standards and those standards need to be rigorously enforced by the federal government."

The Department of Labor does not track the percentage of unemployment benefits that have been processed, an agency spokeswoman said in an email. The agency did not offer a comment on the issue of delays in processing benefits.

But previously unreleased data compiled by Andrew Stettner, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, illustrates the scope. By the end of May, about 18.8 million out of 33 million claims — 57 percent — had been paid nationwide. That number has steadily improved from 47 percent of paid claims at the end of April and 14 percent at the end of March.

In Wisconsin, where about 13 percent of claims remained unprocessed as of July 7, residents told local reporters that they had waited 10 weeks or longer for their claims to be processed, leaving some on the brink of bankruptcy and eviction. The Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development said through a spokesman that the average time from application to payment is 21 days. In Pennsylvania, another 15 percent of claims were still in review as of mid-June.

Oklahoma has approved 235,000 out of about 590,000 claims, with about 2,000 still under review as of June 21, but the state also has denied a whopping 350,000 claims, said Shelley Zumwalt, the interim director of the Oklahoma Employment Security Commission. Zumwalt said a small portion of the denied claims — about 47,000 — are people who have applied for the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), a program for gig and self-employed workers who must get rejected from regular unemployment insurance before qualifying for the expanded benefit for gig workers.

Nevada has also had issues processing these gig worker jobless claims, fulfilling only 74 percent of the 106,667 eligible PUA claims by June 19.

Samuel Jarman, 25, filed for unemployment in Oklahoma in early April, after his start date at a new job to work on software for a payroll services company was pushed back indefinitely. Jarman said the issues he's had collecting unemployment insurance were part of the reason he moved back to his parents' house.

It took nearly eight weeks to get his first payment, a lump sum of all the benefits he was owed at that point. But last month, his claim was flagged for fraud, and his payments stopped, he said. He doesn't know why his claim was flagged for fraud. But at one point, one of the people who helped him with his claim over the phone asked him for his full social security number — something he thought was suspicious, as workers are not supposed to do that, state officials say.

Jarman has had problems getting through to the unemployment office in recent weeks, ending up trapped in an automated phone system unable to reach anyone with answers. He said he's frustrated by elected officials, like Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt (R), who he feels have not been transparent and fail to take threats raised by the pandemic seriously.

"They keep saying 'unprecedented.' We're four months into this — how unprecedented is it still?" he said. "If you're up front about it, it's a lot better than just lying to our faces saying it's all going smoothly."

Other unemployed workers described similarly time-consuming attempts to navigate unemployment systems.

Kelly Johnson, 48, a restaurant manager and single mother of five in Dunedin, Fla., waited almost two months to receive her first payment after she was furloughed in March. She spent much of April calling the state's Department of Economic Opportunity, about 400 times, she estimates. She wasn't able to get through.

When her payment did finally arrive, it was backdated just two weeks. She said she's given up on recovering any of her owed benefits, or filing another claim to recoup income from personal training work that also evaporated during the pandemic.

So she makes do every week with the $71 she gets from the state as well as the $600 in federal supplemental benefits.

"It's just messed up," she said. "It's an overloaded system."

One problem is that some states have made it tougher to access benefits. Florida was one of many Republican-led states that restricted unemployment benefits in the aftermath of the Great Recession. After sustained lobbying from corporations hoping to reduce unemployment taxes, the state, under then Gov. Rick Scott, limited unemployment to 12 weeks and capped weekly benefits at $275, according to the Orlando Sentinel.

By contrast, unemployed workers in Florida, and across the nation, are temporarily eligible for $600 in supplemental federal benefits every week, but that's slated to expire at the end of the month unless Congress extends them.

A report written in 2017 by Wentworth, the unemployment expert, found those types of changes, which both limit the amount of benefits paid out and add restrictions, disqualifications or higher burdens for workers applying, had drastically reduced the number of unemployed workers collecting benefits in states around the country.

"States that have been the most restrictive in moving people off unemployment insurance — those states have had the hardest time processing claims now," Stettner said in an interview.

The pandemic has brought a multitude of new challenges, according to state unemployment offices. Zumwalt, the newly appointed director of Oklahoma's unemployment agency, said the state's system relies on a mainframe computer from 1978, which has hampered the speed with which it can process large batches of claims.

"Remember the Oregon Trail? That's what my mainframe looks like," she said. "We have many full-time people whose job is just making sure that thing doesn't die."

Zumwalt said staffing at the agency had dropped to 450 from 700 since 2017, although officials are making a push to hire workers.

She also rented out space in a convention center outside of Oklahoma City for the unemployed to get help with outstanding claims, which has improved their ability to process them — from about 170 claims a day to around 500 to 600 now. Claimants are given masks and have their temperature taken before entering, she said.

Still, there is a never-ending list of knots to untangle.

Nearly 200 Vietnamese speakers showed up, unexpectedly, needing help and language assistance one day. A pregnant woman's water broke while she was waiting in line. Others have overheated while waiting on hot summer days. Many of the complaints are complicated to untangle, like those from people like Jarman, the software troubleshooter, who have had claims flagged as fraudulent, in some instances because they've been impersonated, Zumwalt said.

"Every person that walks in my door is angry, and they have a right to be angry," she said.

The state has forwarded 90,000 claims to be investigated for fraud.

Other states systems are similarly bogged down by outdated or poorly designed technology, concerns about fraud and staffing issues. In Nevada, the interim director for the state unemployment system resigned in June after facing threats from angry workers. In Washington state, 100 National Guard members have been called in to help sort through issues around fraudulent cases.

The delays in getting jobless benefits to the unemployed have led to some informal organizing — social media groups with thousands of members have cropped up on Facebook and other sites in states like Wisconsin, Nevada, Florida and Oklahoma.

Are you unemployed due to the pandemic? The Post has a new Facebook group to help you navigate.

-- via my feedly newsfeed