https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/06/an-early-view-of-the-economic-impact-of-the-pandemic-in-5-charts/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

No one should expect the pandemic to alter – much less reverse – tendencies that were evident before the crisis. Neoliberalism will continue its slow death, populist autocrats will become even more authoritarian, and the left will continue to struggle to devise a program that appeals to a majority of voters.

| The latest IMF analysis on the global economic impact of COVID-19 // |

|

| ||||

Payrolls fell by 701,000 in March, their first monthly decline in almost 10 years, and the jobless rate ticked up to 4.4 percent (from 3.5) as the coronavirus and efforts to contain it pounded the U.S. labor market last month. Because of the timing in the surveys in this report, it only picks up the front end of tsunami of layoffs that occurred in the second half of March, when initial claims for Unemployment Insurance rose by almost 10 million, an increase most economists would have considered inconceivable before this crisis. But the report clearly identifies the tip of the wave.

The surveys were fielded in the middle of March, and thus better reflect conditions in the first half of the month, when containment measures were just taking hold. Commerce, travel, and broad consumer activity was slowing but hadn't shut down as they would in March's second half. Even so, the report is far more negative than recent vintages, and shows how remarkably quickly conditions have reversed in the job market.

For example, the 0.9 point increase in the jobless rate was the largest one-month increase since 1975; the 1.7 point increase in the underemployment rate, to 8.7 percent, is the largest increase on record since this measure was introduced in 1994. The Bureau reports that the "bulk of the increase in unemployment occurred among people on temporary layoff, which increased 1.0 million in March to 1.8 million." Measures of labor market participation also fell sharply, a clear reflection of the reversal in labor demand. This shift is especially disheartening as prior to the virus, the tight job market was pulling typically left-behind workers into the job market. Such gains are quickly unraveling, a point I return to below.

As readers know, we typically feature our jobs smoother which averages monthly payroll changes over 3, 6, and 12 month windows in order to pull out the underlying signal. We print the smoother below, but it too is less informative this month, since a backwards looking average by definition downplays the sharp shift in trend that occurred in the past two weeks (to emphasize this point, we include a bar for the 701K loss in March alone).

A better, simpler approach this month is to plot monthly payroll levels, which show the sharp trend reversal in March.

Source: BLS

Hourly pay stayed on track last month, up 3.1 percent and beating inflation that's been running just north of 2 percent, though price growth will likely slow (boosting real wage growth) due to very low energy prices. However, wage trends can be deceptive at times like this because of "composition effects." For example, as more low-wage workers face layoffs relative to high-wage workers, this can show up as accelerating wage growth. I'll try to parse out this potential bias in forthcoming reports.

Different sectors have different degrees of exposure to the jobs impact of the virus, of course. One way to think of this difference is that if you can draw a paycheck by clicking into Zoom meetings, you're in a less exposed sector. So, restaurant, hotel workers, flight attendants and anyone in a face-to-face services (and their suppliers) has a much higher chance of a layoff relative to many in professional services like legal, accounting, or research. The food vendor who works at a professional sports venue is directly exposed; the team's lawyer is not.

For example, employment in restaurants and bars fell by over 400,000 in March, a one-month loss of over 3 percent, by far the sector's worse month on record. Conversely, employment in professional and technical services was up slightly in March, by about 6,000. True, that's a weak month for the sector, and most sectors (outside of those that are directly responsive to containment efforts) are being hit by the sharp downturn. But magnitudes of losses will differ by exposure.

It is far from incidental, of course, that there's an inequality divide implicit in that distinction. A useful analysis from the St. Louis Federal Reserve split workers by occupations into high and lower risk of unemployment. About half of the workforce fell into each category (to be clear, that doesn't mean unemployment will hit 50 percent; not every exposed worker will get laid off). The analysis found that "the highest risk of unemployment also tend to be lower-paid occupations. The average annual earnings of the low-risk occupations is $64,600, about 75% higher than earnings in the high-risk occupations, at $36,600. This indicates the economic burden from this health crisis will most directly affect those workers who are likely in the most vulnerable financial situation."

Source: Charles Gascon, St. Louis Fed.

We've never shut the U.S. economy down as we have done in response to the virus. This was a wholly necessary response to its threat, but it came at point when the labor market was persistently closing in on full employment, providing meaningful employment and wage gains for workers who are often left behind under more slack conditions. Much as full employment provides out-sized benefits for the most vulnerable workers, the reversal we're now witnessing metes out the most pain on those same groups of workers. Many of these laid off workers lack paid leave and their savings rate is zero or negative. That is, they are the least insulated among us against this sort of sudden shock.

That is why our relief efforts must scale to the unprecedented size of the problem. Recent stimulus measures, with their emphasis on checks to household and expanded Unemployment Insurance, are a good start but we a) must ensure these measures are quickly implemented, and b) we will need further trips back to this well.

The risk at times like these–risks we've seen borne out in both the health and economic responses–is doing too little. As Dr. Fauci said the other day (paraphrasing): If you think I'm overreacting, I'm probably getting it right.

Policymakers have asked—in some cases, demanded—that people stay home and businesses shutter as a public health crisis has unfolded across the United States, inducing an economic downturn. Despite positive developments in legislation passed last week, those policymakers have not put in place all the steps needed to protect workers and businesses from a full-scale recession that may cast a shadow for years to come. Given the likely scope and scale of this crisis and the current public policy response—which, from both a public health and economic perspective, has been insufficient—it is looking increasingly likely that the United States may be on the cusp of a severe economic recession.

What does the evidence from the Great Recession of 2007–2009 say about what an extended recession could mean for working people over the long term, especially young workers?

There is extensive research on the effects that economic downturns have on workers' employment and earnings, not just during a recession but also lingering for years and decades afterward. In a new working paper, University of California, Berkeley economist Jesse Rothstein finds that workers who happen to be entering the labor market when there's a recession have both permanently lower employment rates and lower earnings long after the recession has ended. These effects for recent entrants are even worse than for other members of the U.S. labor force who have been in it longer, as Rothstein explains in a column about the paper:

Workers from these cohorts saw their annual employment rates drop by 2 percentage points to 4 percentage points per year, relative to older workers in the same labor market. Those who were established in the workforce by the beginning of the recession—those who graduated college in 2005 and earlier—essentially returned to prerecession levels of employment by 2014. But those who entered after 2005 have not; their employment rates remain depressed even as the overall market has recovered.

Unfortunately, these effects are not temporary. Rothstein estimates that the permanent effects, or scarring, of the Great Recession on young workers will result in those individuals earning 2 percent less through the early years of their careers and will reduce their employment throughout the course of their career by about one week. While these amounts might sound small for one individual, aggregated across an entire generation, they represent a large loss of earnings and employment.

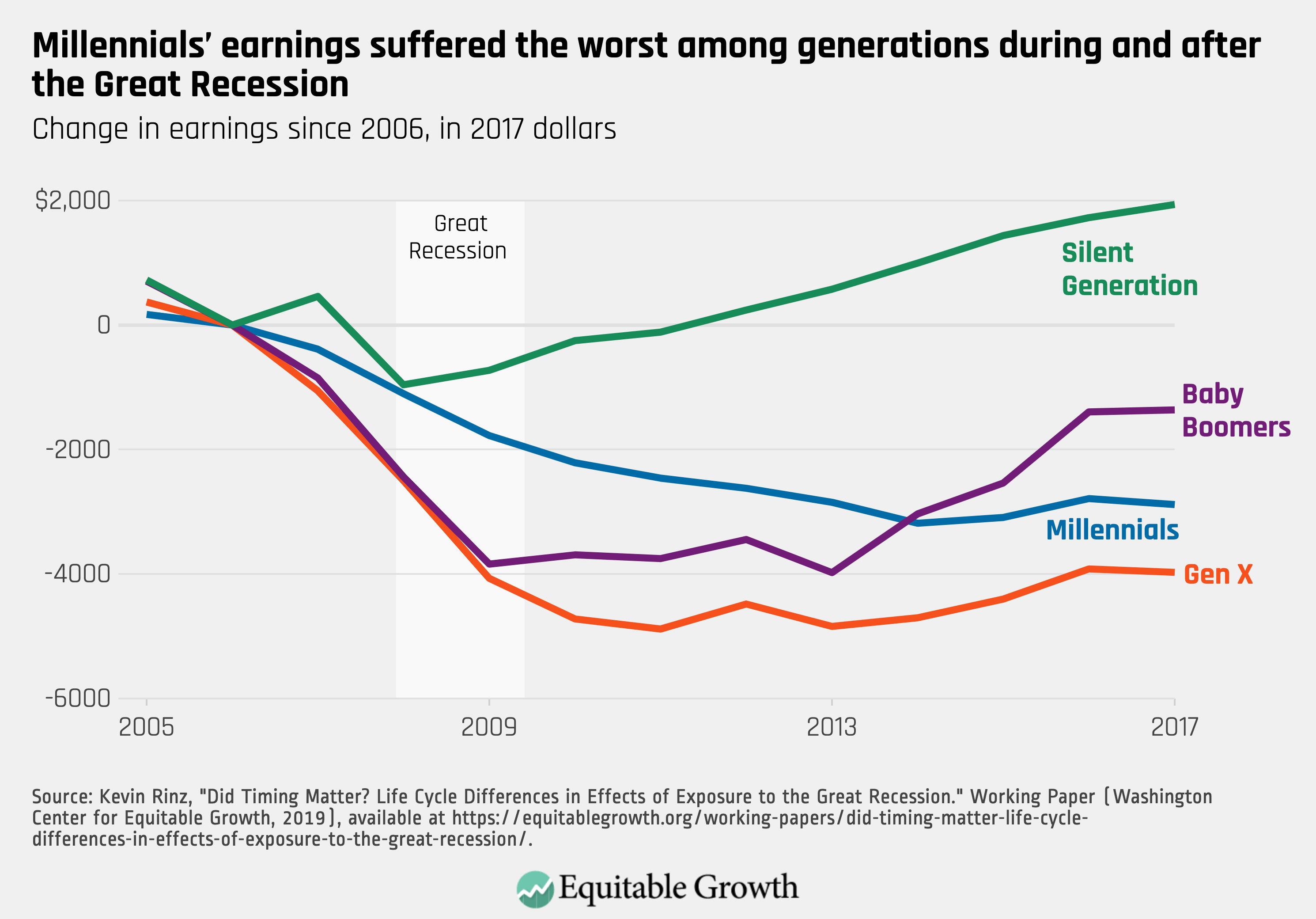

Another new working paper that explores the negative effects the Great Recession had on young workers in particular is by U.S. Census Bureau economist Kevin Rinz. He finds that from 2007 to 2017, millennials whose local labor markets had higher unemployment lost 13 percent in cumulative earnings, compared to 9 percent for Generation X and 7 percent for the baby-boom generation. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

These worse earnings outcomes relative to older workers persisted even as these millennials were more likely to be employed again by 2017. Rinz then discusses a few different reasons why younger workers' earnings would still be depressed even as their employment improves.

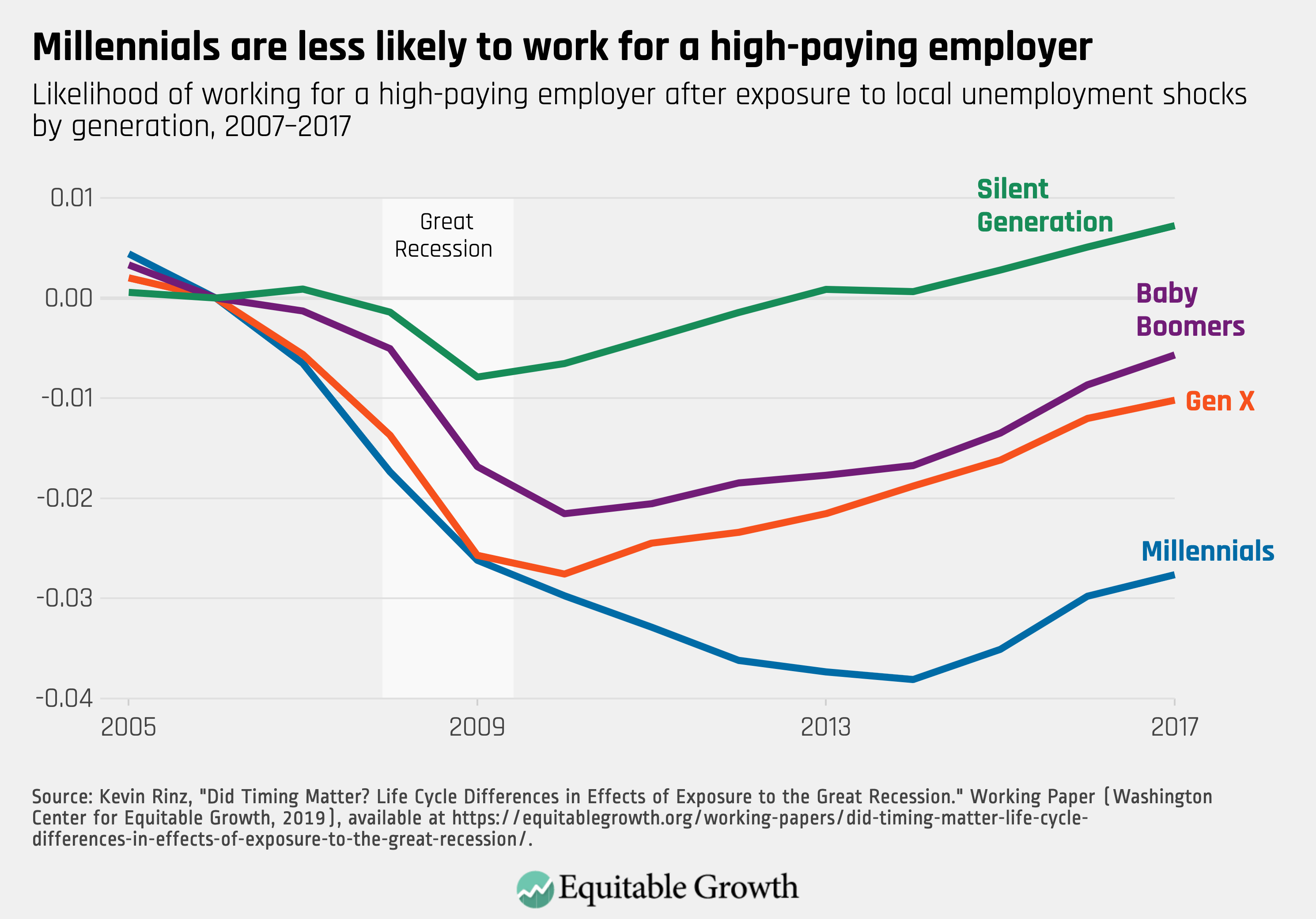

One of those ways is that younger workers, especially millennials, were still less likely to be working for high-paying employers even as their employment recovered. Meanwhile, older workers saw their chances of working for high-paying employers improve roughly proportionately to their likelihood of being employed. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

You can read more about Rinz's paper in this column by Equitable Growth Director of Labor Market Policy Kate Bahn.

One of the reasons it's so concerning to see that recessions have such negative consequences for young workers is because where you start out in the earnings distribution has important implications for your long-term earnings trajectory—even if you don't have the bad luck to be entering the labor market during a recession. Research funded by Equitable Growth by Syracuse University economist Emily Wiemers and University of Massachusetts Boston economist Michael Carr found that people are less likely to move up the earnings distribution over the course of their career than they used to. They find that the likelihood of a worker who starts their career in the middle of the earnings distribution moving to the top decile of the earnings distribution has declined approximately 20 percent over the past 40 years.

This means people are more "stuck in place" in the earnings distribution throughout the course of their careers, with less chance of earning more as they grow older and more experienced. This also means that where one starts on the earnings ladder is more indicative of where you will finish in the earnings ladder than used to be true. This is true even for college-educated workers, who may have higher earnings overall but have actually seen their lifetime earnings mobility decline the most.

The combination of these cyclical factors caused by recessions and structural factors driven by long-term changes in earnings mobility have profound implications for the long-term economic opportunity that young workers face. As my co-author Elisabeth Jacobs and I explain in our report, "Are today's inequalities limiting tomorrow's opportunities?," these changes together represent one way in which even highly skilled and highly "human capitalized" workers face lower prospects of economic mobility relative to prior generations.

This means that while much of our political and policy rhetoric continues to emphasize the role of individual skills, education, and hard work to explain economic outcomes, the reality is that far too often, economic outcomes reflect factors beyond an individual's control, from racial and gender discrimination to the dumb luck of happening to be a young adult entering the labor market during a recession.

Research from the Great Recession indicates that the 2007–2009 downturn had deep and long-lasting negative economic impacts on people. The current downturn caused by our coronavirus-driven economic shutdown has already had dire impacts on workers, seen last week in the unprecedented jump in Unemployment Insurance claim filings. But as we have seen from the research above, recessions' negative economic effects also linger for years afterward in depressed earnings and employment, and this current downturn may linger even longer due to underlying fragilities in the U.S. economy caused by historically high economic inequality and a porous social safety net.

That's why it's crucial that policymakers take swift and decisive action to ensure not only that income keeps flowing in the short term but also that permanent, inequality-fighting policy changes are enacted to improve the country's safety net and enhance automatic fiscal stabilizers in the long term. The legislation enacted last week is a good down payment on that goal, but further interventions may be needed as our economy continues to suffer from the consequences of the coronavirus.

Lisa Cook

To cushion the blow of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Congress last week passed and President Donald Trump signed the $2.2 trillion emergency stimulus package, including provisions to send checks of up to $1,200 to each tax-paying citizen and hundreds of billions of dollars more to small businesses to cushion the blow for their laid-off employees. The flow of this emergency relief from the federal government should prioritize low-wage earners, who are at significant health, economic, and financial risk due to the coronavirus and the looming recession. Mobile payments, using electronic transfers and mobile applications, could get money into their hands quickly.

A record number of people are losing jobs. In Michigan, Monday through Thursday last week, 80,000 people, many of whom are low-wage workers, filed Unemployment Insurance claims—a number which exceeds the 60,000 filings at the peak of unemployment following the Great Recession of 2007–2009. Across the United States, nearly 3.3 million people filed for Unemployment Insurance this past week, with expectations of millions more doing so in April.

Low-wage workers, who account for 44 percent of all U.S. workers (roughly 53 million people), are their families' primary wage earners. These breadwinners are disproportionately women and minorities who live paycheck to paycheck and are therefore most at risk. With no income, these workers are unable to pay bills—rent, mobile phone, health insurance, car and student loans, and mortgages. Consumer spending drives more than two-thirds of Gross Domestic Product. Every bill they cannot pay (to a landlord, a mortgage lender, or a car company) and every business they cannot patronize (their mechanic, favorite restaurant, or neighborhood clothing store) starts a chain reaction that will only deepen this coronavirus recession.

Too little of this federal emergency relief money may well get into these consumers' hands too late. Most people and small businesses have bills due at the end of the month. They need cash immediately. Direct payments will eventually reach most small businesses and families, but getting these funds to them could take several weeks or perhaps much longer. The most vulnerable who do not file taxes and do not receive benefits, such as Social Security, will be the hardest to reach.

Mobile money could be the answer. The federal government should learn from the decades-long experience with mobile money in developing countries and more recently in the United States. Mobile phone networks sent all Americans with a cell phone an emergency text alert this past October. They could get them money today, especially the most vulnerable.

Mobile payments use electronic transfers and mobile applications. In the United States, mobile payments connect to banks and other financial institutions. Ninety-six percent of American adults have cell phones, and 81 percent have a smartphone that could receive and make mobile payments. Thirty percent of smartphone users made mobile payments in 2019, and this amount was projected to grow before the COVID-19 pandemic. Mobile payments are faster than traditional payments and offer a good way to send money to the 16 percent of Americans who are underbanked.

Smartphone penetration is high among workers most likely to be missed by traditional payment mechanisms—people who have changed addresses and low-wage earners. Ninety-eight percent of adults ages 18 to 29 have smartphones, compared to 81 percent of adults overall. Nearly three-quarters of those earning less than $30,000 have smartphones. The share of African Americans (80 percent) and Hispanics (79 percent) who own smartphones is comparable to the total, but there are larger shares of blacks (23 percent) and Hispanics (25 percents) who use smartphones rather than broadband at home compared to whites (12 percent), according to the Pew Research Center.

Mobile payments preserve the value of the per-person amount distributed by the government by limiting high fees associated with using bank alternatives. With mobile payments, the recipient can choose a platform, such as Zelle and Paypal/Venmo, to connect to a bank. Most services have caps on daily transfers ($2,000 for Zelle and $10,000 for PayPal) and other security features to prevent fraud.

For all Americans, and especially the underbanked, the federal government's forthcoming stimulus payments should be made available by allowing people to decide which credit union, community bank, or commercial bank to use with a guarantee of no or minimal fees for the recipient. Financial institutions should be reimbursed a small flat rate for these transactions. The U.S. Treasury Department should then use community banks, credit unions, and commercial banks affiliated with mobile payment platforms to facilitate not only the distribution of this emergency relief cash but onward mobile payments to landlords, mortgage servicers, and other creditors. Zelle, for example, is affiliated with 766 such financial institutions across the country.

This possibly very sharp but short economic downturn or an even longer recession is happening at an unparalleled pace. Mobile payments can get cash out fast, particularly to the most vulnerable.

—Lisa D. Cook is a professor of economics at Michigan State University. She was a senior economist at the White House Council of Economic Advisers and led the Harvard University team advising Rwanda on its first post-genocide IMF program.

CAMBRIDGE – Crises come in two variants: those for which we could not have prepared, because no one had anticipated them, and those for which we should have been prepared, because they were in fact expected. COVID-19 is in the latter category, no matter what US President Donald Trump says to avoid responsibility for the unfolding catastrophe. Even though the coronavirus itself is new and the timing of the current outbreak could not have been predicted, it was well recognized by experts that a pandemic of this type was likely.

Add to Bookmarks

PreviousNext

SARS, MERS, H1N1, Ebola, and other outbreaks had provided ample warning. Fifteen years ago, the World Health Organization revised and upgraded the global framework for responding to outbreaks, trying to fix perceived shortcomings in the global response experienced during the SARS outbreak in 2003.

In 2016, the World Bank launched a Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility to provide assistance to low-income countries in the face of cross-border health crises. Most glaringly, just a few months before COVID-19 emerged in Wuhan, China, a US government report cautioned the Trump administration about the likelihood of a flu pandemic on the scale of the influenza epidemic a hundred years ago, which killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide.

Just like climate change, COVID-19 was a crisis waiting to happen. The response in the United States has been particularly disastrous. Trump downplayed the severity of the crisis for weeks. By the time infections and hospitalizations began to soar, the country found itself severely short of test kits, masks, ventilators, and other medical supplies.

The US did not request test kits made available by the WHO, and failed to produce reliable tests early on. Trump declined to use his authority to requisition medical supplies from private producers, forcing hospitals and state authorities to scramble and compete against one another to secure supplies.

Delays in testing and lockdowns have been costly in Europe as well, with Italy, Spain, France, and the United Kingdom paying a high price. Some countries in East Asia have responded a lot better. South Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong appear to have controlled the spread of the disease through a combination of testing, tracing, and strict quarantine policies.

Interesting contrasts have emerged within countries as well. In northern Italy, Veneto has done much better than nearby Lombardy, largely owing to more comprehensive testing and earlier imposition of travel restrictions. In the US, the neighboring states of Kentucky and Tennessee reported their first cases of COVID-19 within a day of each other. By the end of March, Kentucky had only a quarter of the number of cases as Tennessee, because the state acted much more quickly to declare a state of emergency and close down public accommodations.

For the most part, though, the crisis has played out in ways that could have been anticipated from the prevailing nature of governance in different countries. Trump's incompetent, bumbling, self-aggrandizing approach to managing the crisis could not have been a surprise, as lethal as it has been. Likewise, Brazil's equally vain and mercurial president, Jair Bolsonaro, has, true to form, continued to downplay the risks.

On the other hand, it should come as no surprise that governments have responded faster and more effectively where they still command significant public trust, such as in South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan.

China's response was typically Chinese: suppression of information about the prevalence of the virus, a high degree of social control, and a massive mobilization of resources once the threat became clear. Turkmenistan has banned the word "coronavirus," as well as the use of masks in public. Hungary's Viktor Orbán has capitalized on the crisis by tightening his grip on power, by disbanding parliament after giving himself emergency powers without time limit.

The crisis seems to have thrown the dominant characteristics of each country's politics into sharper relief. Countries have in effect become exaggerated versions of themselves. This suggests that the crisis may turn out to be less of a watershed in global politics and economics than many have argued. Rather than putting the world on a significantly different trajectory, it is likely to intensify and entrench already-existing trends.

Momentous events such as the current crisis engender their own "confirmation bias": we are likely to see in the COVID-19 debacle an affirmation of our own worldview. And we may perceive incipient signs of a future economic and political order we have long wished for.

So, those who want more government and public goods will have plenty of reason to think the crisis justifies their belief. And those who are skeptical of government and decry its incompetence will also find their prior views confirmed. Those who want more global governance will make the case that a stronger international public-regime health could have reduced the costs of the pandemic. And those who seek stronger nation-states will point to the many ways in which the WHO seem to have mismanaged its response (for example, by taking China's official claims at face value, opposing travel bans, and arguing against masks).

In short, COVID-19 may well not alter – much less reverse – tendencies evident before the crisis. Neoliberalism will continue its slow death. Populist autocrats will become even more authoritarian. Hyper-globalization will remain on the defensive as nation-states reclaim policy space. China and the US will continue on their collision course. And the battle within nation-states among oligarchs, authoritarian populists, and liberal internationalists will intensify, while the left struggles to devise a program that appeals to a majority of voters.