https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-24/countries-are-starting-to-hoard-food-threatening-global-trade

We're tracking the latest on the coronavirus outbreak and the global response. Sign up here for our daily newsletter on what you need to know.

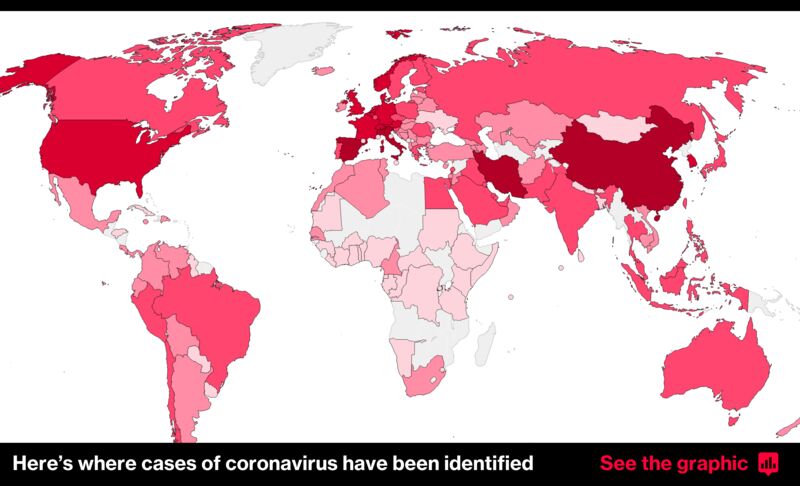

It's not just grocery shoppers who are hoarding pantry staples. Some governments are moving to secure domestic food supplies during the conoravirus pandemic.

Kazakhstan, one of the world's biggest shippers of wheat flour, banned exports of that product along with others, including carrots, sugar and potatoes. Vietnam temporarily suspended new rice export contracts. Serbia has stopped the flow of its sunflower oil and other goods, while Russia is leaving the door open to shipment bans and said it's assessing the situation weekly.

To be perfectly clear, there have been just a handful of moves and no sure signs that much more is on the horizon. Still, what's been happening has raised a question: Is this the start of a wave of food nationalism that will further disrupt supply chains and trade flows?

Shoppers wait on the street for the general opening of the store, during a time set aside for elderly and vulnerable members of the community to shop, at an Iceland Foods store in London on March 18.

Photographer: Simon Dawson/Bloomberg

"We're starting to see this happening already -- and all we can see is that the lockdown is going to get worse," said Tim Benton, research director in emerging risks at think tank Chatham House in London.

Though food supplies are ample, logistical hurdles are making it harder to get products where they need to be as the coronavirus unleashes unprecedented measures, panic buying and the threat of labor crunches.

Consumers across the globe are still loading their pantries -- and the economic fallout from the virus is just starting. The specter of more trade restrictions is stirring memories of how protectionism can often end up causing more harm than good. That adage rings especially true now as the moves would be driven by anxiety and not made in response to crop failures or other supply problems.

As it is, many governments have employed extreme measures, setting curfews and limits on crowds or even on people venturing out for anything but to acquire essentials. That could spill over to food policy, said Ann Berg, an independent consultant and veteran agricultural trader who started her career at Louis Dreyfus Co. in 1974.

"You could see wartime rationing, price controls and domestic stockpiling," she said.

Some nations are adding to their strategic reserves. China, the biggest rice grower and consumer, pledged to buy more than ever before from its domestic harvest, even though the government already holds massive stockpiles of rice and wheat, enough for one year of consumption.

Key wheat importers including Algeria and Turkey have also issued new tenders, and Morocco said a suspension on wheat-import duties would last through mid-June.

Food Dependence

Trade as a share of domestic food supply

Source: UN's Food & Agriculture Organization Global Perspectives Studies

As governments take nationalistic approaches, they risk disrupting an international system that has become increasingly interconnected in recent decades.

Kazakhstan had already stopped exports of other food staples, like buckwheat and onions, before the move this week to cut off wheat-flour shipments. That latest action was a much bigger step, with the potential to affect companies around the world that rely on the supplies to make bread.

For some commodities, a handful of countries, or even fewer, make up the bulk of exportable supplies. Disruptions to those shipments would have major global ramifications. Take, for example, Russia, which has emerged as the world's top wheat exporter and a key supplier to North Africa. Vietnam is the third-largest rice exporter, sending many of its cargoes to the Philippines.

"If governments are not working collectively and cooperatively to ensure there is a global supply, if they're just putting their nations first, you can end up in a situation where things get worse," said Benton of Chatham House.

He warned that frenzied shopping coupled with protectionist policies could eventually lead to higher food prices -- a cycle that could end up perpetuating itself.

"If you're panic buying on the market for next year's harvest, then prices will go up, and as prices go up, policy makers will panic more," he said.

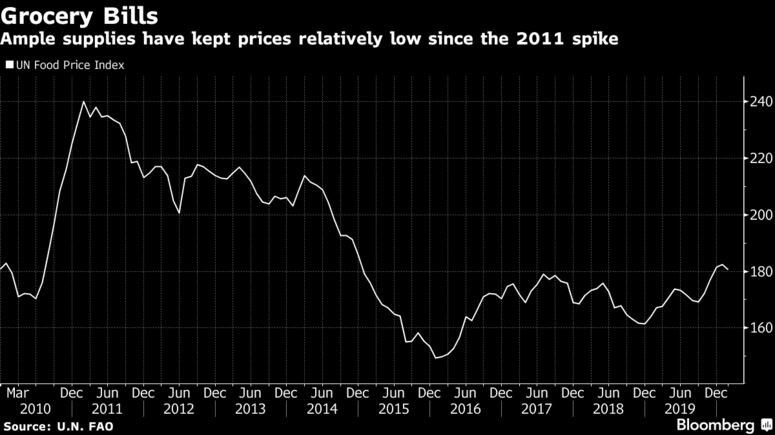

And higher grocery bills can have major ramifications. Bread costs have a long history of kick-starting unrest and political instability. During the food price spikes of 2011 and 2008, there were food riots in more than 30 nations across Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

"Without the food supply, societies just totally break," Benton said.

Unlike previous periods of rampant food inflation, global inventories of staple crops like corn, wheat, soybeans and rice are plentiful, said Dan Kowalski, vice president of research at CoBank, a $145 billion lender to the agriculture industry, adding he doesn't expect "dramatic" gains for prices now.

While the spikes of the last decade were initially caused by climate problems for crops, policies exacerbated the consequences. In 2010, Russia experienced a record heat wave that damaged the wheat crop. The government responded by banning exports to make sure domestic consumers had enough.

The United Nations' measure of global food prices reached a record high by February 2011.

"Given the problem that we are facing now, it's not the moment to put these types of policies into place," said Maximo Torero, chief economist at the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization. "On the contrary, it's the moment to cooperate and coordinate."

Of course, the few bans in place may not last, and signs of a return to normal could prevent countries from taking drastic measures. Once consumers start to see more products on shelves, they may stop hoarding, in turn allowing governments to back off. X5 Retail, Russia's biggest grocer, said demand for staple foods is starting to stabilize. In the U.S., major stores like Walmart Inc. have cut store hours to allow workers to restock.

In the meantime, some food prices have already started going up because of the spike in buying.

Wheat futures in Chicago, the global benchmark, have climbed more than 6% in March as consumers buy up flour. U.S. wholesale beef has shot up to the highest since 2015, and egg prices are higher.

At the same time, the U.S. dollar is surging against a host of emerging-market currencies. That reduces purchasing power for countries that ship in commodities, which are usually priced in greenbacks.

In the end, whenever there's a disruption for whatever reason, Berg said, "it's the least-developed countries with weak currencies that get hurt the most."

— With assistance by Yuliya Fedorinova, and Anatoly Medetsky

-- via my feedly newsfeed