U.S. Stocks Tumble With Stimulus Details Uncertain: Markets Wrap

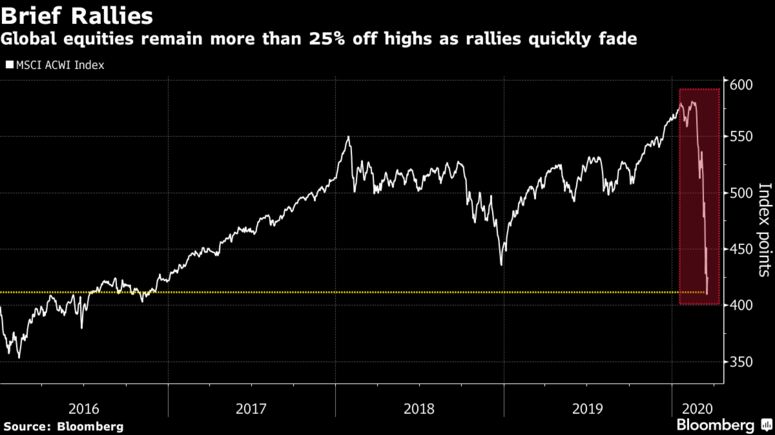

Financial markets spasmed, sending U.S. stocks down to levels in December 2018 and Bloomberg's dollar index to a record, as the economic fallout from the pandemic outpaced the massive response from governments and central banks.

The S&P 500 fell more than 7%, triggering a 15-minute pause, with stocks adding to losses when trading resumed. The next halt would occur at a 13% decline. The Dow Jones Industrial Average wiped out all the gains logged since Donald Trump's inauguration, dropping as much as 10%, with investors craving more government spending to offset the impact from the virus.

Bonds tumbled around the world a day after Treasuries notched biggest yield jump since 1982, while municipal bonds extended the deepest rout since 1987 as markets braced for the potential flood of spending. Oil dropped to an 18-year low. The dollar strengthened a seventh straight day, while the pound hit its lowest level against the greenback since 1985.

Trump offered few details at a press briefing on the details his Treasury secretary is discussing with Congress. The Federal Reserve dusted off crisis-era programs to stabilize financial markets.

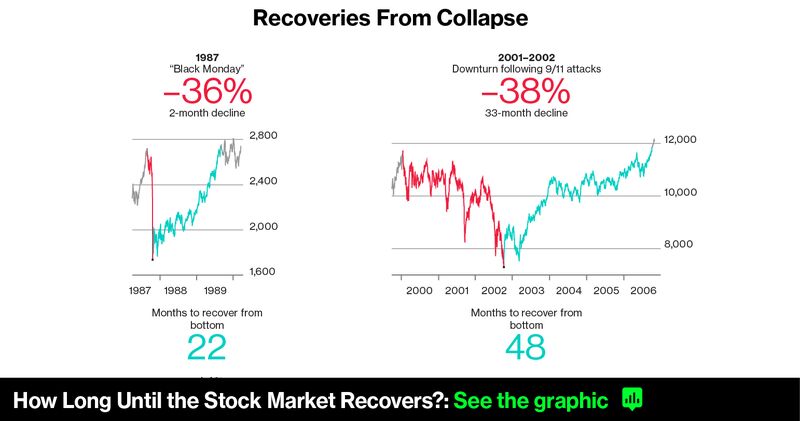

Governments have pledged or are considering massive fiscal support to offset the economic shock from the pandemic, with the Trump administration moving toward a big package, but the virus continues to spread at a pace that is forcing massive shutdowns across the globe.

"The missing fundamental ingredient for a sustainable recovery in risk appetite is some evidence that the growth of global Covid-19 infection rates is peaking," said Paul O'Connor, head of multi-asset at Janus Henderson Investors. "Clearly, we are not there yet."

The planned U.S. stimulus could amount to $1.2 trillion, aiming to stave off the worst impact of a crisis that already looks set to plunge many of the world's economies into recession. Meantime, the Federal Reserve reintroduced additional crisis-era tools to stabilize financial markets. Those responses came after stresses appeared in the short-term funding markets.

"I don't think we're out of the woods yet in terms of liquidity," Mark Konyn, chief investment officer at AIA Group in Hong Kong, told Bloomberg TV. "It's a question of when the fiscal measures will have the most efficacy."

In Germany, Angela Merkel said the government will not rule out joint European Union debt issuance to help contain the impact.

| READ MORE |

|---|

| Travel Curbs Extend With Cases Exceeding 193,000: Virus Update |

| Trump Told Mnuchin to Go Big, and a $1 Trillion Stimulus Emerged |

| Global Bonds Plunge on Fear of Debt Deluge From Pandemic Defense |

Elsewhere, Bloomberg's industrial-metals index dropped for a third day, with copper, nickel and aluminum among the biggest losers. Gold resumed losses as traders sold the metal to cover margin calls in other markets.

These are the main moves in markets:

Stocks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bonds |

|

|

|

|

Commodities |

|

|