https://www.epi.org/blog/coronavirus-shock-will-likely-claim-3-million-jobs-by-summer/

At this point, a coronavirus recession is inevitable. But the policy response can determine how deep it is, how long it lasts, and how rapidly the economy bounces back from it.

If this response includes enough fiscal stimulus that is well-targeted and sustained so long as the economy remains weak, job loss will be substantially reduced relative to any scenario where policymakers drag their feet. Even with moderate fiscal stimulus, we're likely to see 3 million jobs lost by summertime. Keeping this number down and allowing any job loss to be quickly recouped after the crisis ends should spur policymakers to act.

Put simply, the federal government needs to finance a much larger part of household consumption in coming months, transfer significant fiscal aid to state governments, and ramp up direct government purchases (particularly on items helpful in fighting the epidemic).

Forecasting the number of jobs lost

Currently, the closely watched Goldman Sachs economic outlook is forecasting 0% growth for the first quarter of this year and −5% contraction (expressed as an annualized rate) for the second quarter. Given the cratering of demand already evident in data from restaurant reservations and airlines and accommodations, this may already be an overly optimistic forecast, but we'll stick with it for now. This forecast implies that the economy will shrink by roughly 1.25% from January to June (2.5% at annualized rates for half a year). Given that productivity growth (or output growth divided by hours of work) has been rising at roughly 1.25% in recent years, output growth of 0.75% is needed just to keep job growth from falling below zero in these months. (The intuition is that if output growth was zero for an entire year, and the amount of output produced in a given hour rose by 1.25%, then 1.25% fewer hours of work would be needed in the economy.)

If output growth actually contracts by 1.25% between January and June, this implies a loss in employment of roughly 2% (1.25% reduction from output contraction and 0.75% reduction from productivity growth), or more than 3 million jobs lost. If the actual number of jobs lost by the end of the summer is anywhere near this large, it will represent a pace of job loss comparable to the very worst months of the Great Recession. The unique nature of a coronavirus-driven recession means that the numbers of job losses could diverge substantially from these established, mechanical models of economic forecasts. But this is not cause for complacency—some forecasts for growth in coming quarters are even a bit worse than the Goldman Sachs projection.

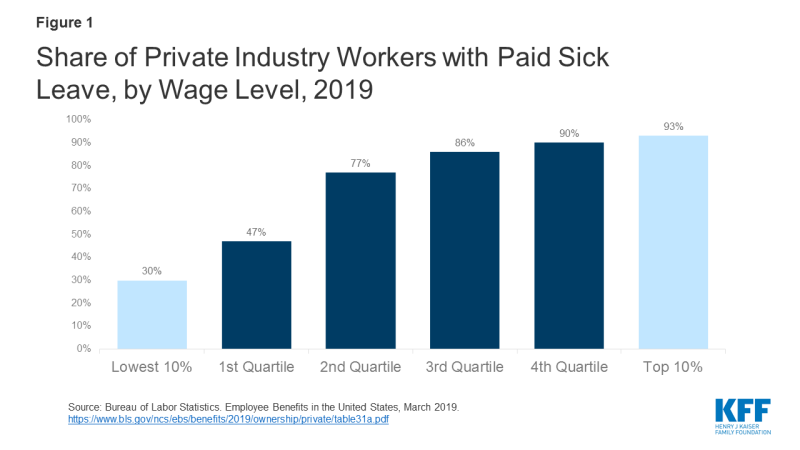

One argument against this kind of mechanical calculation is that output losses are often substantially greater than job losses in recessions. In typical recessions, the first wave of job losses tends to include substantial losses in manufacturing jobs. However, a coronavirus recession is much more laser-targeted at low-wage, low-productivity, and low-hours jobs in service industries. This should increase job loss relative to output loss. Given that workers in these sectors are likely to have very little savings to tide them over the economy's downturn, the ripple effect from the first round of job losses are likely to be far greater.

A big and fast fiscal stimulus is needed to stem job losses and boost recovery

Policy will play a key role in determining the ultimate number of Americans who lose their jobs due to this outbreak. Goldman forecasts a return to growth in the 3rd quarter, but this forecast is largely driven by their assumption that a fiscal stimulus of 1-2% of total gross domestic product (GDP) appears—between $200 and $400 billion. Without at least as much fiscal stimulus as this, output and job losses will be worse. Further, if businesses expect fiscal stimulus to be quick and effective, they may be more willing to "hoard labor" during the downturn—cutting work hours back or even putting workers on temporary rather than permanent layoffs. This labor hoarding would help cushion the shock during the recession and could boost the speed of recovery.

After hopefully passing a second round of coronavirus response early this week, Congress must get right back to work passing a macroeconomic stimulus package, one large enough and well-targeted enough to fill in the substantial hole in demand that will be left by the coronavirus economic shock.

Household consumption in coming months will crater as people engage in "social distancing," but the depth of the decline will depend in part on the fiscal response. Housing, utilities, food, health care, and other consumption possibilities unaffected by social distancing constitute well over a half of all consumption spending. And some of the decline in consumption spending necessitated by social distancing will be substituted by other types of consumption spending: People will spend less in restaurants and more on groceries in coming weeks, for example.

When households' incomes fall due to job loss during recessions, their spending on items commonly considered necessities—like food and housing—often falls in turn. So even during the period when economic activity in many sectors is being intentionally suppressed to halt the spread of the virus, there is the opportunity to provide households some income support to keep other types of consumption spending from falling.

Further, having the federal government finance consumption during the downturn will allow households to emerge from the recession with much healthier balance sheets than otherwise, and this can help ensure a more rapid bounce back of economic activity. After maximizing how much income support can be delivered through existing social insurance and safety net programs (including expansions to unemployment insurance, food stamps, and Medicaid, for example), another good idea would be sending out checks of $1,000 for every American adult and $500 for every child. The first checks could arrive roughly a month after a bill was passed and signed by the president. The checks should then continue monthly until economic conditions allow for them to start winding down.

Besides preserving households' balance sheets during the downturn, the economic response should preserve state governments' fiscal capacity as well. State governments will bear a large share of the burden for providing the public health response, and their spending is often quite pro-cyclical due to balanced budget rules—meaning that state spending often collapses just as the economy needs it to be strong. The federal government should take on all state Medicaid spending for the next year to give these governments the capacity to spend as freely as public health demands, and to keep these governments from turning into the anti-stimulus machines they have tended to in past recessions.

Additionally, there should be lots of scope for ramping up direct government spending in coming months. The federal government should significantly increase their purchase of medical equipment for use in the current (and potential future) pandemics. Federally financed field hospitals and testing clinics could greatly aid the medical response and also support aggregate demand.

After the crisis

We should reiterate again that all of this stimulus should come with conditions-based triggers. We have no real idea how quickly the economy might recover from the coronavirus shock, even with an optimal policy response. We shouldn't guess. Instead, we should make sure the economy gets the support it needs so long as spending remains weak.

Finally, once the current crisis has passed, we will need a thorough diagnosis of just why the U.S. economy and society was so fragile to this shock. The already-persuasive case that public investment and social insurance in the United States should be much stronger has been made even more convincing by how unprepared our economy and public health apparatus was for this shock.

-- via my feedly newsfeed