http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2020/02/untangling-indias-distinctive-economic.html

But whatever the plausible reasons why China's economy has gotten more attention than India, it seems clear to me that India's economic developments have gotten far too little attention. A symposium in the Winter 2020 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives offers some insights:

- "Dynamism with Incommensurate Development: The Distinctive Indian Model," by Rohit Lamba and Arvind Subramanian

- "Why Does the Indian State Both Fail and Succeed?" by Devesh Kapur

- "The Great Indian Demonetization," by Amartya Lahiri

Lamba and Subramanian point out that over the 38 years from 1980 (when India started making some pro-business reforms), India is one of only nine countries in world to have averaged an annual growth rate of 4.5%, with no decadal average falling below 2.9% annual growth. (The nine, listed in order of annual growth rates during this time with highest first, are Botswana, Singapore, Korea, Taiwan, Malta, Hong Kong, Thailand, India, and Malaysia.) Of course, one can tweak these cutoffs in various ways, but no matter how you slice it, India's growth rate over the last four decades has been remarkable. Moreover, India's population is likely to exceed China's in the near future.

But India's path to rapid growth has been notably different than many other countries. India is ethnically fractionalized, especially when the caste system is taken into account.In addition, India path to development has been "precocious," as Lamba and Subramanian put it, in two ways.

One involves the "modernization hypothesis" that economic development and democracy evolve together over time. In India, universal suffrage arrived all at once when India became independent in 1948. For a sense of how dramatic this difference is, the graph below shows per capita GDP on the horizontal axis and degree of democracy on the vertical axis. The lines show the path of countries over time. Clearly, India defies the modernization hypothesis by having full democracy before development. China defies the modernization hypothesis in the other direction, by having develoment without democracy.

The other precocious factor for India is that economic development in most countries involves a movement from agriculture to manufacturing to services. However, India has largely skipped the stage of low-wage manufacturing, and moved directly toward a services-based economy. One underlying factor is India's "license raj"--the interlocking combinations of rules about starting a business, labor laws, and land use that have made it hard for manufacturing firms to become established. A related factor is that in global markets, India's attempts at low-wage manufacturing over the decades were outcompeted by Korea, Thailand, China--and now by the rise of robots.

The good side of this "precocious servicification" is that that high-income economies are primarily services and services are a rising part of international trade. The bad side is that this services economy works much better for the relatively well-educated in urban areas, and offers less opportunity for others--thus leading to greater inequality.

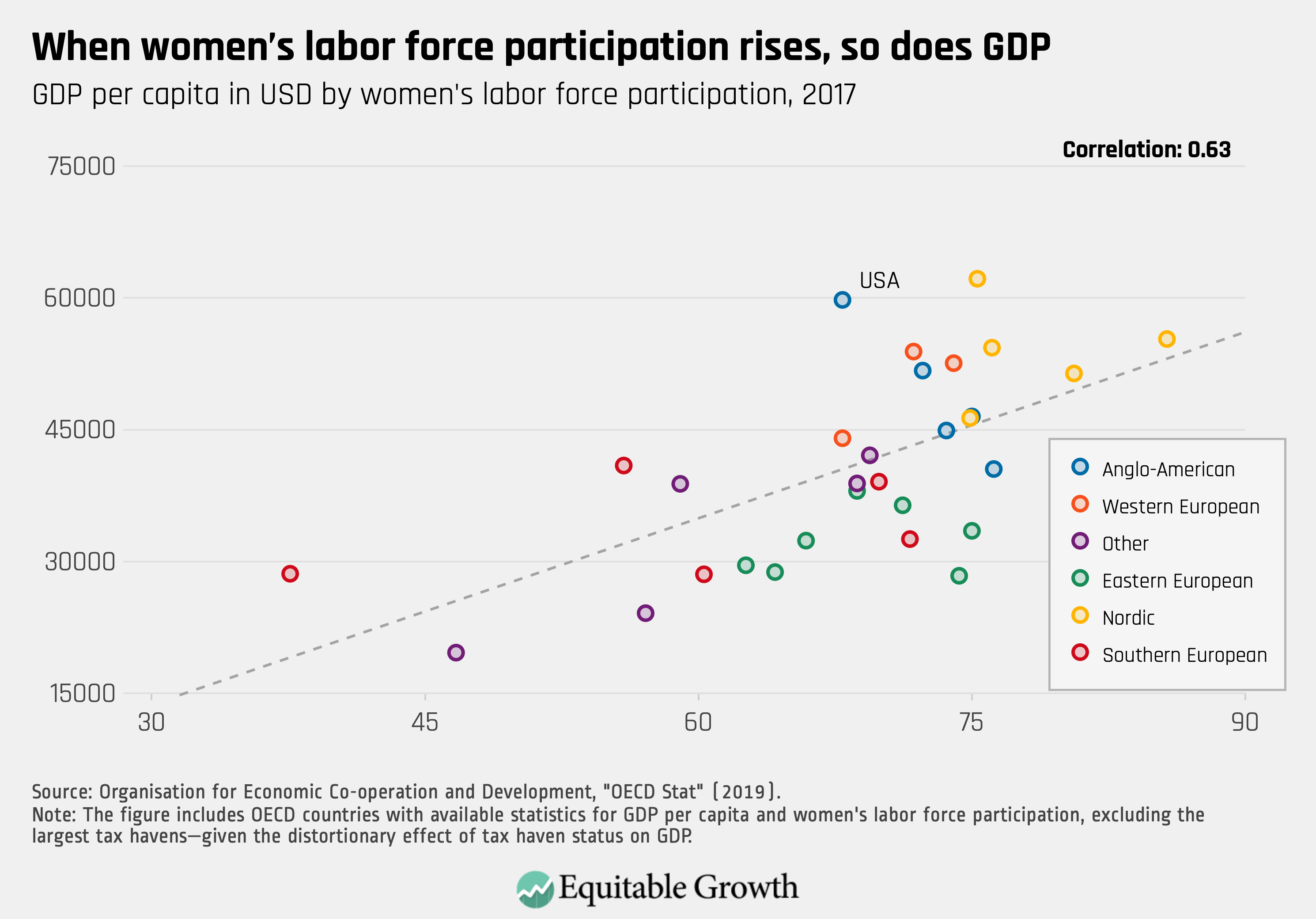

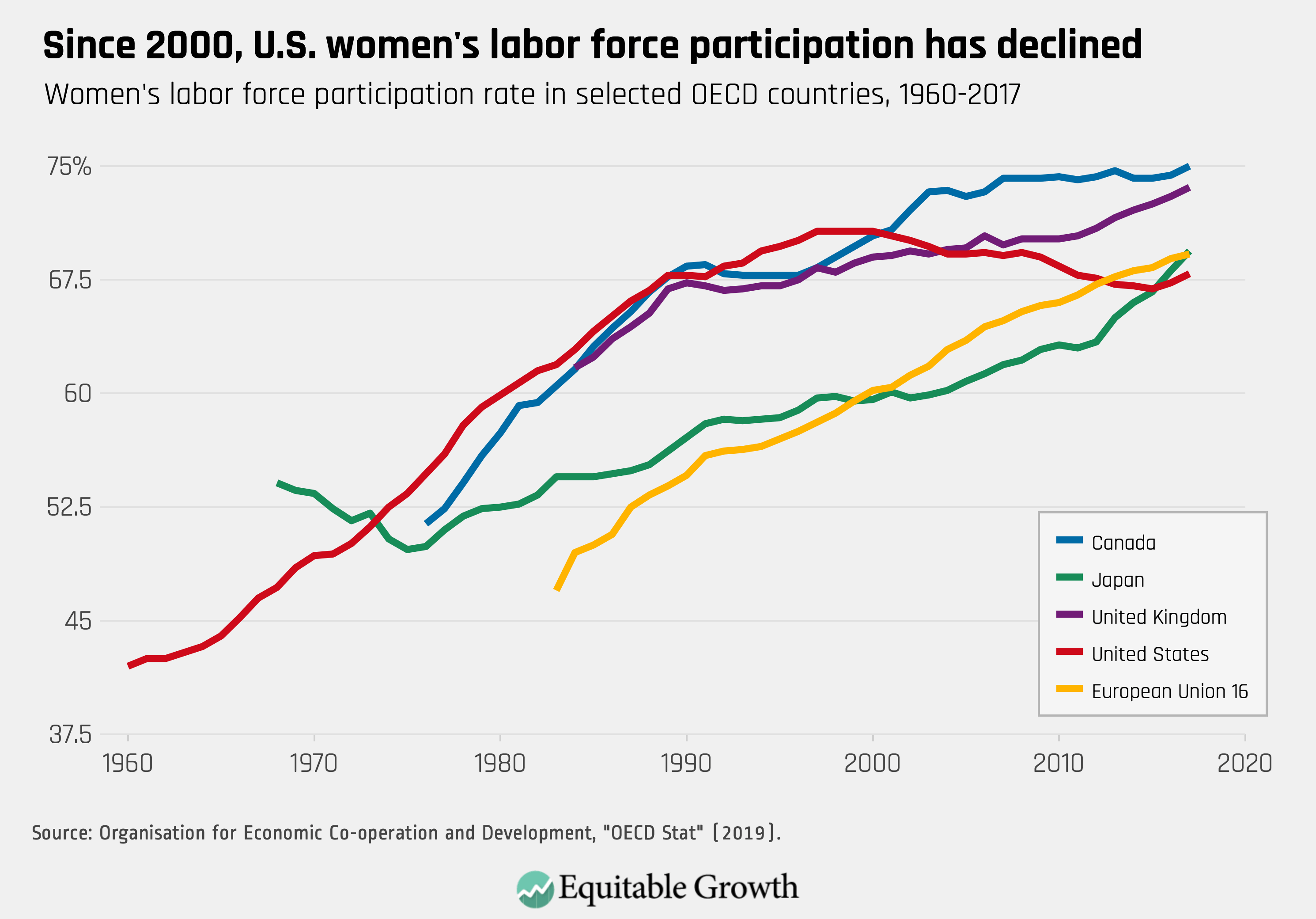

India faces a range of other issues as well. Environmental problems in India are severe: when it comes to air pollution for example, "22 of the top 30 most polluted cities in the world are in India." The role of women in India's economy and society is in some ways moving backward: "Female labor force participation in India has been declining from about 35 percent in 1990 to about 28 percent in 2015. For perspective, the female labor force participation rate in Indonesia in 2015 was almost 50 percent; in China, it was above 60 percent. In addition, the gap between India's labor force participation rate and the rate of countries with similar per capita GDP is widening, not narrowing. ... India's sex ratio at birth increased from 1,060 boys born for every 1,000 girls in 1970 to 1,106 in 2014, widening its gap from the biological norm of 1,050."

The capabilities of India's government are shaped by these underlying background factors. Devesh Kapur writes in JEP:

India's state performs poorly in basic public services such as providing primary education, public health, water, sanitation, and environmental quality. While it is politically effective in managing one of the world's largest armed forces, it is less effective in managing public service bureaucracies. The research literature on India has many discussions of programs that fail to deliver meaningful outcomes, or that are victims of weak implementation and rent-seeking behavior of politicians and bureaucrats, or that are vitiated by discrimination against certain social groups ...

But on the other side, the Indian state has a strong record in successfully managing complex tasks and on a massive scale. It has repeatedly conducted elections for hundreds of millions of voters—nearly 900 million in the 2019 general elections—without national disputes. In this decade, it has scaled up large programs such as Aadhaar, the world's largest biometric ID program (which crossed one billion people enrolled within seven years of its launch). Most recently, it has implemented the integrated Goods and Services Tax (GST), one of the most ambitious tax reforms anywhere in recent times. India ranks low on its ability to enforce contracts, but its homicide rate has dropped markedly from 5.1 in 1990 to 3.2 (per 100,000) in 2016 ...

[T[he Indian state has delivered better in certain situations and settings: specifically, on macroeconomic rather than microeconomic outcomes; where delivery is episodic with inbuilt exit, rather than where delivery and accountability are quotidian and more reliant on state capacity at local levels; and on those goods and services where societal norms and values concerning hierarchy and status matter less, rather than in settings where these norms and values—such as caste and patriarchy—are resilient.

Kapur traces these issues back to the ethnic fractionalization, social cleavages and caste system in India, combined with India's early adoption of democracy. Moroever, India is a country with a low tax/GDP ratio and a relatively small number of taxpayers. He also points out that most government positions in India require a difficult civil-service examination, and by international standards India's government does not appear overstaffed. A pattern has evolved that India's government is relatively effective on big picture projects like electrification, but much less effective on local issues that are related to social expectations about caste and gender: for example, reforms related to education, or the welfare of children and women. In countries as different as the United States and China, about 60% of all government employees are at the local level; in India, it's less than 20%.

India continues to have issues with caste differences, as explored in the article by Kaivan Munshi. he writes:

Caste continues to play an important role in the Indian economy. Networks organized at the level of the caste or jatiprovide insurance, jobs, and credit for their members in an economy where market institutions are inefficient. Affirmative action for large groups of historically disadvantaged castes in higher education and India's representative democracy has, if anything, made caste more salient in society and in the public discourse. Newly available evidence with nationally representative data indicates that there has been convergence in education, income, occupations, and consumption across caste groups over time. ... The available evidence indicates that caste discrimination, at least in urban labor markets, is statistical, that is, based on differences in socioeconomic characteristics between upper and lower castes. ... Given the strong intergenerational persistence in human capital, the key variable driving convergence, it will be many generations before income and consumption are equalized across caste groups.

The caste-based economic networks that currently serve many functions will also disappear once markets begin to function efficiently. These networks continue to be active in the globalizing Indian economy because information and commitment problems are exacerbated during a period of economic change. In the long run, however, the markets will settle into place and the caste networks will lose their purpose. This has certainly been the experience in many developed countries. In the United States, for example, ethnic networks based on a European country (region) of origin supported their members through the nineteenth century into the middle of the twentieth century. Ultimately, however, these networks no longer served a useful role and today, outside of a few pockets, European ethnic identity in the United States is largely symbolic. We might expect caste to similarly lose its salience as India develops into a modern market economy, and there is some evidence that this process may have already begun.Amartya Lahiri takes up yet another issue: "On November 8, 2016, India demonetized 86 percent of its currency in circulation." Specifically, India declared that people needed to turn in their large-denomination bills at banks, and that the existing bills would be worthless moving forward. They would then be replaced with new currency. The policy had several goals, like making it impossible for organized crime to hide its accumulated gains in the form of cash, and bringing people into the banking system and the digital economy. But Lahiri argues that these larger goals were not much affected by the change. Instead, the main effect of the demonetization was causing short-term hardship and higher unemployment in the areas where the demonetization led to temporary cash shortages. I had not known that India had carried out similar demonetizations of large-denomination currency in 1946 and 1978--with, Lahiri argues, much the same minimal-to-negative effects.

India's record of sustained and strong economic growth appears to be in some danger from the "twin balance sheet challenge." As Lamba and Subramanian put it:

The sustainability of growth—which in late 2019 has cratered to a near standstill— will be determined by structural factors salient amongst which is the "twin balance sheet challenge" initiated by the toxic legacy of the credit boom of the 2000s. Recently, the rot of stressed loans has spread from the public sector banks to the nonbank financial sector, and on the real side, from infrastructure companies to most notably the real estate sector with the latter threatening middle class savings. This contagion owes both to overall weak economic growth and slow progress in cleaning up bank and corporate balance sheets. A failure to resolve this challenge could mean a reprisal of the Japanese experience of nearly two decades of lost growth, but at a much lower level of per capita income. India's development experience could end up being a transition from socialism without entry to capitalism without exit because weak regulatory capacity and lack of social buy-in will have impeded the necessary creative destruction.Thus, India's economy finds itself at a pivotal moment, facing both the short-run challenges of the twin balance sheet problem, the longer run economic problems of appropriate reforms to create an environment in which India's businesses can function and grow, the challenges of building transportation, energy, and communications infrastructure., and the social policy challenges of improving education and health care. Challenges never come singly.

For some previous posts on India's economy, see:

- "The Jobs Problem in India" (October 8, 2019)

- "India Economic Survey: Challenges Accepted" (July 26, 2019)

- "India: What's Needed for Sustained Growth?" (March 22, 2017)

- "The Economic Vision for Precocious, Cleavaged India" (February 16, 2017)

- "India's Economic Growth: Puzzles, Issues, Sustainability" (January 3, 2012

-- via my feedly newsfeed