By Nancy J. Altman, a writing fellow for Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute, has a 40-year background in the areas of Social Security and private pensions. She is president of Social Security Works and chair of the Strengthen Social Security coalition. Her latest book is The Truth About Social Security. She is also the author of The Battle for Social Security and co-author of Social Security Works! Produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Donald Trump's recent budget proposal included billions of dollars in Social Security cuts. The proposed cuts were a huge betrayal of his campaign promise to protect our Social Security system. Fortunately for Social Security's current and future beneficiaries, he has little chance of getting these cuts past the House of Representatives, which is controlled by Democrats.

So Trump and his budget director/chief of staff Mick Mulvaney, who has long been hostile to Social Security, are trying another tactic to cut our earned benefits. They are pursuing a long game to reach their goal. In a divide-and-conquer move, the focus is not Social Security. At least, not yet.

Last week, the Trump administration revealed that it is planning to employ the so-called chained Consumer Price Index (CPI) in a way that does not need congressional approval. "Chained CPI" might sound technical and boring, but anyone who has closely followed the Social Security debate knows better. It has long been proposed as a deceptive, hard-to-understand way to cut our earned Social Security benefits.

Trump plans to switch to the chained CPI to index the federal definition of poverty. If he succeeds, the impact will be that over time, fewer people will meet the government's definition of poverty — even though in reality, they will not be any less poor. The definition is crucial to qualify for a variety of federal benefits, including Medicaid, as well as food and housing assistance. The announcement was written blandly about considering a variety of different measures, but anyone who knows the issue well can easily read the writing on the wall.

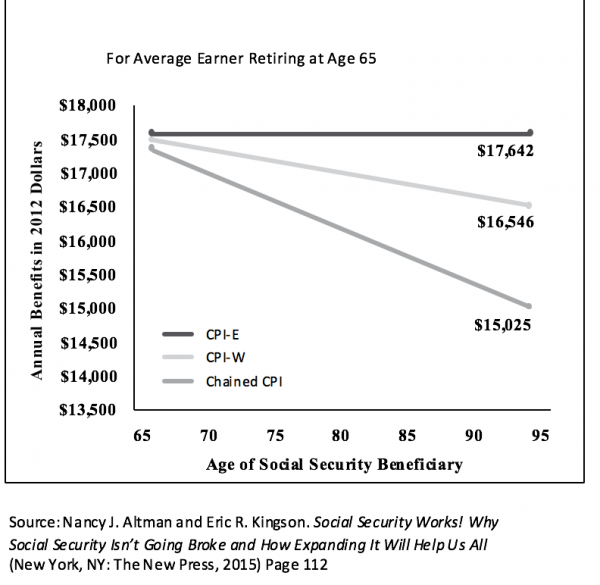

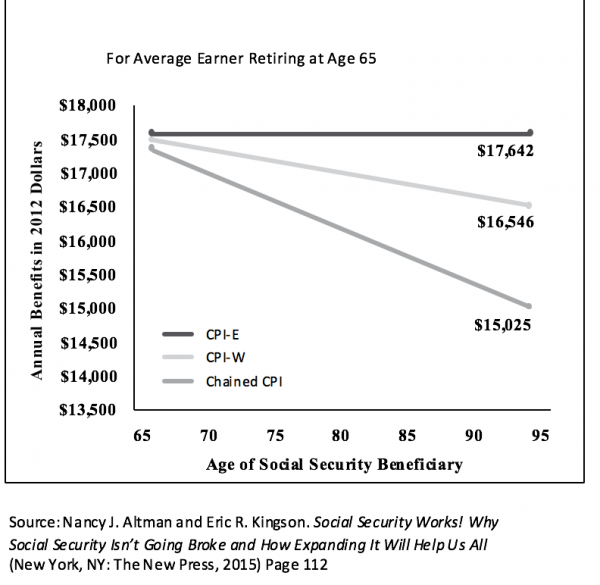

So, what does this have to do with Social Security? Like the poverty level, Social Security's modest benefits are automatically adjusted to keep pace with inflation. If not adjusted, those benefits will erode, slowly but inexorably losing their purchasing power over time. These annual adjustments are already too low, but they are better than no adjustment at all. The chained CPI would make these adjustments even less adequate. The top line of the following chart shows what a more accurate adjustment would look like. The line below it shows what the current adjustment does to benefits, and the bottom line shows what the stingier chained CPI would do:

Proponents of the chained CPI say that it is better at measuring "substitution," but don't be fooled. The current inadequate measure already takes into account substitution of similar items. This is the idea that if the price of beef goes up, you can substitute chicken. In contrast, the chained CPI involves what are called substitutions across categories. If your planned vacation abroad goes up, you can stay home and buy a flat screen television and concert tickets instead.

Of course, neither form of substitution is much help to seniors and people with disabilities whose health care costs are skyrocketing. There's no substitution for hospital stays and doctor visits. Those who propose the chained CPI are apparently fine with letting seniors who can't afford even chicken substitute cat food.

The idea of substitution within or across categories makes no sense for people with no discretionary income. If all of your money goes for medicine, food and rent, how does substitution make sense? If you are so poor that your children go to bed hungry, how do you substitute?

Back in 2012, President Barack Obama proposed a so-called Grand Bargain to cut Social Security using the chained CPI, in return for Republicans agreeing to increase taxes on the wealthy. The goal of this Grand Bargain was ostensibly to reduce the deficit, despite the fact that Social Security does not add a single penny to the deficit.

Grassroots activists around the country fought back, and Obama ultimately realized his error. He removed the chained CPI from his budget proposals and endorsed expanding, rather than cutting, Social Security's modest benefits. Social Security expansion is now the official positiono f the Democratic Party.

Yet Republicans have still continued to push Social Security cuts, including the chained CPI. Back in December 2017, they passed a massive tax cut for corporations and the super-wealthy. Afterwards, they used the predictable deficits their tax cuts caused as an excuse to call for cutting Social Security. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and other Republicans made well-publicized statements about the so-called "need" to cut Social Security. What was much more secret was a provision in the tax bill which replaced the measure used to index the tax brackets with the chained CPI.

Now, Trump wants to apply the chained CPI to the calculation of poverty rates. This will directly hurt many seniors and people with disabilities by making it more difficult to qualify for Medicaid and other programs many of them rely on, including food and housing assistance. It is also a long-term threat to Social Security itself.

The strategy is clear: Trump and his Republican supporters in Congress plan to apply chained CPI everywhere else, and then say that it is only common sense and indeed fair that we apply it to Social Security as well. We should be consistent, right?

Trump thinks that he can get away with executing this long-game attack on Social Security quietly, while the media and public are focused on his tweets, name calling, and scandals. But we must not be distracted. If we do not stop this attack in its tracks, our earned benefits will be next.

If you want to forestall another fight over cutting Social Security through the chained CPI, call your members of Congress, write to your local paper, and tell your friends: No chained CPI! No chained CPI for our earned benefits! No chained CPI for the most vulnerable among us!

This quiet effort to embed the chained CPI is a fight Trump does not want to have, certainly in an election year. But it is one we will bring to him. Grassroots activism defeated the chained CPI before. This time it will be harder because Trump can substitute the chained CPI without legislation. That means we have to simply fight harder. If we stick together, we surely will win. And we must. All of our economic security depends on it.