Harpers Ferry, WV

Friday, May 3, 2019

NBER:U.S. Consumers Have Borne the Brunt of the Current Trade War

Harpers Ferry, WV

Millions of workers are paid less than the ‘average’ minimum wage [feedly]

https://www.epi.org/blog/millions-of-workers-are-paid-less-than-the-average-minimum-wage/

Last week, the New York Times published an article in "The Upshot" by Ernie Tedeschi, which argues that after accounting for state and local minimum wages, the United States currently has its highest average effective minimum wage ever at $11.80 per hour. The article correctly underscores how after 10 years of inaction at the federal level, so much of the policy work being done to boost wages for low-wage workers is happening at the state and local level. Yet, it is important to recognize that even with state and local governments taking action in many places, there are still millions of workers being paid significantly lower wages than the "average" minimum wage as calculated in the Upshot piece. In fact, raising the federal minimum wage to $11.80 would directly lift wages for 18.6 million workers, or 12.8 percent of the wage-earning workforce. Moreover, calculating the average effective minimum wage is very sensitive to how one defines the workforce affected by the policy. One would arrive at a much lower average minimum wage if considering the broader low-wage workforce for whom minimum wage policy is relevant.

The Upshot piece explores how the share of workers being paid exactly the federal minimum wage is relatively small. There are two reasons why this is the case. First, the article observes that 89 percent of minimum-wage workers are paid more than the federal $7.25, because 29 states and some 40+ cities and counties have set their own minimum wages above the federal floor. Higher state and local minimum wages—all of which can be found in EPI's Minimum Wage Tracker—are the result of federal inaction and also due to the tremendous success of the Fight for 15 movement in raising awareness about low wages and pushing for minimum wage increases across the country.

Second, the share of workers being paid the federal minimum wage potentially overlooks millions of workers in states with low minimum wages who are earning only somewhat above the required federal minimum. For example, in Texas, a state stuck at the federal minimum wage, 2.7 percent of workers reported earning less than $7.50 per hour last year. But four times as many workers in Texas, or 11.0 percent, earned less than $10.00 per hour. This contrasts sharply with California, where there are higher state and local minimum wages: there, only 3.8 percent of the workforce reported earning less than $10.00 per hour last year. (These calculations use Current Population Survey data.)

This raises some important questions about how the average minimum wage should be calculated. The Upshot article's methodology states that $11.80 is the average minimum wage "weighted by the usual labor hours of minimum wage workers at nonfarm wage and salary jobs paid hourly." However, because minimum wages influence wage levels for more than just those workers right at the statutory minimum, we can instead calculate the minimum wage faced by the entire labor market (not just those earning exactly the minimum wage). The employment-hours-weighted average minimum wage of the entire U.S. workforce is $9.33, substantially below the $11.80 calculated in the Upshot piece.

The reason these numbers are so different is that higher state and local minimum wages will have an outsized influence when limiting the calculation to those workers being paid exactly the minimum wage. Whenever the minimum wage is raised, it compresses the lower end of the wage distribution, creating a spike in the number of workers earning the new minimum wage. This means that, all else being equal, there is always going to be a larger share of workers who are minimum wage workers in areas that have adopted higher minimum wages. As a result, when calculating the average minimum wage weighted by employment at the minimum wage, San Francisco's $15 minimum wage would likely be weighted more heavily than Texas' $7.25 even if Texas has more workers paid a wage only slightly above its legal minimum.

A better way to measure the extent of low wages, despite state and local minimum wage hikes, is by considering how many workers would be affected if the federal minimum wage were raised to the average value identified in the Upshot piece. Using EPI's minimum wage simulation model, we estimate that if the federal minimum wage were raised to $11.80, it would directly lift wages for 18.6 million workers (12.8 percent of the wage-earning workforce.) In other words, simply raising the minimum to the Upshot-calculated average of $11.80 would significantly raise the pay of millions of workers held back by low minimum wages in states and localities throughout the country. Moreover, raising the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2024 would lift pay for nearly 40 million workers, including millions across the country who haven't benefited from a higher state and local minimum wage. Low statutory minimum wages and low wages actually paid to workers are much more prevalent than the Upshot-calculated average suggests and the best way to address this is by raising the federal minimum wage.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

The PRO Act: Giving workers more bargaining power on the job [feedly]

Yet, I do not believe all the reforms are enough to get the job done that needs doing. They are based, essentially on a RETURN to the Wagner Act of 1936 which declared the policy of the US government was to ENCOURAGE collective bargaining. The Wagner Act and its subsequent corrupt and anti-labor cousin, The Taft Hartley Act were both based on labors right to strike and by doing so exercise market power in a (usually) local labor market. The law reflected both American culture and reality of industrial relations of the time, which were assumed to be fundamentally adversarial. At no time the the law contemplate the gig economy, nor the rise of services and technical occupations, nor the rise of monopoly power globally to the point where local labor market power was nearly meaningless for big corps.

https://www.epi.org/blog/the-pro-act-giving-workers-more-bargaining-power-on-the-job/

Our economy is out of balance. Corporations and CEOs hold too much power and wealth, and working people know it. Workers are mobilizing, organizing, protesting, and striking at a level not seen in decades, and they are winning pay raises and other real change by using their collective voices.

But, the fact is, it is still too difficult for working people to form a union at their workplace when they want to. The law gives employers too much power and puts too many roadblocks in the way of workers trying to organize with their co-workers. That's why the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act—introduced today by Senator Murray and Representative Scott—is such an important piece of legislation.

The PRO Act addresses several major problems with the current law and tries to give working people a fair shot when they try to join together with their coworkers to form a union and bargain for better wages, benefits, and conditions at their workplaces. Here's how:

- Stronger and swifter remedies when employers interfere with workers' rights. Under current law, there are no penalties on employers or compensatory damages for workers when employers illegally fire or retaliate against workers who are trying to form a union. As a result, employers routinely fire pro-union workers, because they know it will undermine the organizing campaign and they will face no real consequences. The PRO Act addresses this issue, instituting civil penalties for violations of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). Specifically, the legislation establishes compensatory damages for workers and penalties against employers (including penalties on officers and directors) when employers break the law and illegally fire or retaliate against workers. Importantly, these back pay and damages remedies apply to workers regardless of their immigration status. The PRO Act also requires the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to go to court and get an injunction to immediately reinstate workers if the NLRB believes the employer has illegally retaliated against workers for union activity. With this reform, workers won't be out of a job and a paycheck while their case works its way through the system. Finally, the PRO Act adds a right for workers to go to court to seek relief, bringing labor law in line with other workplace laws that already contain this right. And, the legislation prohibits employers from forcing workers to waive their right to class or collective litigation.

- More freedom to organize without employer interference. The PRO Act streamlines the NLRB election process so workers can petition to form a union and get a timely vote without their employer interfering and delaying the vote. The act makes clear it is workers' decision to file for a union election and that employers have no standing in the NLRB's election process. It prohibits companies from forcing workers to attend mandatory anti-union meetings as a condition of continued employment. If the employer breaks the law or interferes with a fair election, the PRO Act empowers the NLRB to require the employer to bargain with the union if it had the support of a majority of workers prior to the election. And the PRO Act reinstates an Obama administration rule, which was repealed by the Trump administration, to require employers to disclose the names and payments they make to outside third-party union-busters that they hire to campaign against the union.

- Winning first contract agreements when workers organize and protecting fair share agreements. The law requires employers to bargain in good faith with the union chosen by their employees to reach a collective bargaining agreement—a contract—addressing wages, benefits, protections from sexual harassment, and other issues. But employers often drag out the bargaining process to avoid reaching an agreement. More than half of all workers who vote to form a union don't have a collective bargaining agreement a year later. This creates a discouraging situation for workers and allows employers to foster a sense of futility in the process. The PRO Act establishes a process for reaching a first agreement when workers organize, utilizing mediation and then, if necessary, binding arbitration, to enable the parties to reach a first agreement. And the PRO Act overrides so-called "right-to-work" laws by establishing that employers and unions in all 50 states may agree upon a "fair share" clause requiring all workers who are covered by—and benefit from—the collective bargaining agreement to contribute a fair share fee towards the cost of bargaining and administering the agreement.

- Protecting strikes and other protest activity. When workers need economic leverage in bargaining, the law gives them the right to withhold their labor from their employer—to strike—as a means of putting economic pressure on the employer. But court decisions have dramatically undermined this right by allowing employers to "permanently replace" strikers—in other words, replace strikers with other workers so the strikers no longer have jobs. The law also prohibits boycotts of so-called "secondary" companies as a means of putting economic pressure on the workers' employer, even if these companies hold real sway over the employer and could help settle the dispute. The PRO Act helps level the playing field for workers by repealing the prohibition on secondary boycotts and prohibiting employers from permanently replacing strikers.

- Organizing and bargaining rights for more workers. Too often, employers misclassify workers as independent contractors, who do not have the right to organize under the NLRA. Similarly, employers will misclassify workers as supervisors to deprive them of their NLRA rights. The PRO Act tightens the definitions of independent contractor and supervisor to crack down on misclassification and extend NLRA protections to more workers. And, the PRO Act makes clear that workers can have more than one employer, and that both employers need to engage in collective bargaining over the terms and conditions of employment that they control or influence. This provision is particularly important given the prevalence of contracting out and temporary work arrangements—workers need the ability to sit at the bargaining table with all the entities that control or influence their work lives.

The PRO Act does not fix all the problems with our labor law, but it would address some fundamental problems and help make it more possible for workers to act on their federally-protected right to join together with their coworkers to bargain with their employer for improvements at their workplace. Research shows that workers want unions. There is a huge gap between the share of workers with union representation (11.9 percent) and the share of workers that would like to have a union and a voice on the job (48 percent). The PRO Act would take a major step forward in closing that gap.

For more information on the importance of unions and collective bargaining to working people and our economy, see the materials developed in connection with Building Worker Power: A Project of the AFL-CIO and the Economic Policy Institute.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Tuesday, April 30, 2019

Krugman: The Zombie Style in American Politics [feedly]

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/29/opinion/republican-party-ideas.html

Russia didn't help Donald Trump's presidential campaign. O.K., it did help him, but the campaign itself wasn't involved. O.K., the campaign had a lot of Russian contacts and knowingly received information from the Russians, but that was perfectly fine.

It's all very strange. Or, more accurately, it can seem very strange if you still think of the G.O.P. as a normal political party, one that adopts policy positions and then defends those positions in more or less good faith.

But if you have been following Republican arguments over the years, you know that the party's response to evidence of Russian intervention in 2016 is standard operating procedure. On issue after issue, what you see are multiple levels of denial combined with a refusal ever to give up an argument no matter how completely it has been discredited.

ADVERTISEMENT

I first encountered this style of argument a long time ago, over the issue of rising inequality. By the early 1990s it was already obvious that growth in the United States economy was becoming ever more skewed, with huge gains for a small minority at the top but lagging incomes for the middle class and the poor. This was an awkward observation for a party that, then as now, wanted to slash taxes for the rich and dismantle the social safety net. How would conservatives respond?

The answer was multilayered denial. Inequality wasn't rising. O.K., it was rising, but that wasn't a problem. O.K., rising inequality was unfortunate, but there was nothing that could be done about it without crippling economic growth.

You might think that the right would have to choose one of those positions, or at least that once you'd managed to refute one layer of the argument, say by showing that inequality was indeed rising, you could put that argument behind you and move on to the next one. But no: Old arguments, like the wights in "Game of Thrones," would just keep rising up after you thought you had killed them.

And this is still going on. Even as you read about the superrich buying $240 million apartments and demanding ever-bigger mega-yachts, there's a whole industry of people denying that inequality has gone up.

You see the same thing on climate change. Global warming is a myth — a hoax concocted by a vast conspiracy of scientists around the world. O.K., the climate is changing, but it's a natural phenomenon that has nothing to do with human activity. O.K., man-made climate change is real, but we can't do anything about it without destroying the economy.

E

ADVERTISEMENT

As in the case of inequality, refuted climate arguments never go away. Instead, they become intellectual zombies that should be dead but just keep shambling along. If you think Republican arguments on climate have gotten more sophisticated, wait for the next snowstorm; I guarantee you'll hear the same crude denialist arguments — the same willful confounding of climate with daily weather fluctuations — we've been hearing for decades.

What the right's positioning on inequality, climate and now Russian election interference have in common is that in each case the people pretending to be making a serious argument are actually apparatchiks operating in bad faith.

What I mean by that is that in each case those making denialist arguments, while they may invoke evidence, don't actually care what the evidence says; at a fundamental level, they aren't interested in the truth. Their goal, instead, is to serve a predetermined agenda.

Thus, inequality denial is about using whatever argument comes to hand to defend policies that benefit the rich at the expense of working Americans. Climate denial is about using whatever argument comes to hand to defend fossil fuel interests. Russia denial is about using whatever argument comes to hand to defend Donald Trump.

All of this is or should be obvious. After all, it's a pattern that goes back decades. But my sense is that the news media continue to have a hard time coping with the essential fraudulence of most big policy debates. That is, reporting about these debates typically frames them as disputes about the facts and what they mean, when the reality is that one side isn't interested in the facts.

I understand the pressures that often lead to false equivalence. Calling out dishonesty and bad faith can seem like partisan bias when, to put it bluntly, one side of the political spectrum lies all the time, while the other side doesn't.

But pretending that good faith exists when it doesn't is unfair to readers. The public deserves to know that the big debates in modern U.S. politics aren't a conventional clash of rival ideas. They're a war in which one side's forces consist mainly of intellectual zombies.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Dean Baker: What We Have Learned From the Trump Tax Cut [feedly]

http://cepr.net/publications/op-eds-columns/what-we-have-learned-from-the-trump-tax-cut

What We Have Learned From the Trump Tax Cut

Dean Baker

Truthout, April 29, 2019

We're now well into the second year of the Trump tax cut, and we're still waiting for the investment boom. By its own criterion, the Trump tax cut has failed badly, but there are a few lessons worth learning before trashing it as a complete failure. First, and most importantly, the tax cut did provide a boost in demand, leading to faster economic and wage growth and a lower unemployment rate.

The bulk of the tax cut took the form of a reduction in the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. As has been widely reported, this led to a surge in share buybacks, as companies could find nothing better to do with the extra cash than pay it out to shareholders.

Those shareholders spent much of the money they got, driving up consumption by 2.9 percent in the year from the third quarter of 2017 (the last quarter before the tax cut was approved) to the third quarter of 2018. That's up from growth of just 2.4 percent the prior year. Growth also got a boost from higher federal spending, mostly military, which grew by 5 percent in 2018 after growing just 1.3 percent in 2017.

This boost to growth led to more rapid job creation, pushing the unemployment rate down to its current 3.8 percent level. (It had been as low as 3.7 percent for two months last fall.) This is a really big deal. Most economists had not previously thought the unemployment rate could get this low without causing spiraling inflation.

While we may start to see issues with inflation in the future, there is essentially zero evidence of any uptick in the inflation rate to date. This means that we were able to get the unemployment rate down, employing perhaps another million workers. These workers were disproportionately from the most disadvantaged segments of the labor market — people of color, workers with less education and people with criminal records.

The tighter labor market also led to a modest uptick in the rate of wage growth. This has averaged 3.3 percent over the first three months of 2019, up from 2.5 percent in the last three months of 2017.

All of this has come with no noticeable uptick in interest rates. Many warned that the larger budget deficits that resulted from the tax cut would lead to higher interest rates, which would crowd out investment. As it stands, the interest rate on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds is just 2.53 percent. This compares to interest rates of more than 5 percent back in the late 1990s, when the federal government was running budget surpluses.

Once again, economists show themselves to be incredibly bad at recognizing the economy's potential. Back in the late 1990s, virtually all economists agreed that the unemployment rate could not get much below 6 percent without triggering spiraling inflation. They were shown to be wrong in a big way as the unemployment rate averaged 4 percent in 2000, with no noticeable uptick in inflation.

Most economists put the floor for the unemployment rate at or above 5 percent, just a few years back. By pressing the economy to produce at higher levels of output, the tax cut showed the floor is clearly under 4 percent, and perhaps quite a bit lower.

This doesn't change the fact that a tax cut targeted to the rich and corporations was a terrible way to boost demand. We should have done it by investing in infrastructure, education, child care and other productive uses. If we were going to do tax cuts, they should be targeted to the low- and moderate-income people who need it most.

We also learned — if anyone still needed this lesson — that tax cuts to the rich and corporations are not a good way to boost investment. There is little difference in the pace of investment growth pre- and post-tax cut. Orders for non-defense capital goods, the largest category of investment, are up just 11.2 percent from their level of two years ago. This translates into annual growth of just 5 percent, compared to a promised boom in the neighborhood of 30 percent.

The promises that lower corporate tax rates would be associated with the end of loopholes also failed to pan out. After the tax cut passed, the Congressional Budget Office projected the government would collect $243 billion in corporate income taxes in 2018. The government actually collected$205 billion in 2018, a shortfall of almost 20 percent. Apparently, even with the lower rates, the loopholes are still there.

In short, we can say that those of us who thought the Trump tax cut was a pointless giveaway to the rich were right. But those who complained that it was some budget buster that was going to cause high-interest rates and seriously damage the economy were wrong. There was (and may still be) further room to increase demand. It is a good thing that we are testing the economy's limits, even if we are doing it in the worst possible way.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Monday, April 29, 2019

Sen. Warren’s debt cancellation plan: Should progressive policy aim for narrow targets or structural change? [feedly]

http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/sen-sen-warrens-debt-cancellation-plan-should-progressive-policy-aim-for-narrow-targets-or-structural-change/

Introduction

Sen. Warren's college debt cancellation plan, which I explain here, has gotten a mixed reception. While many progressives and, predictably, student debt holders give it high praise, it has taken flak from two broad groups: those who just don't like cancelling debt and those who view it as insufficiently progressive. The latter group objects to the extent to which it helps higher income debtholders who, in their view, don't need the help relative to those with lower incomes.

Their critique provides a microcosm of a major policy debate for Democrats between progressive targeting on one side versus a broader approach aimed at reducing structural inequalities that have grown to historical proportions. It's an important debate, as it plays out in Medicare for All versus Medicare for More, subsidized jobs for targeted groups versus guaranteed jobs for all, universal income support versus targeted wage subsidies, and so on.

This essay starts by examining the rationale for college debt relief and then uses Warren's higher education plan to try to garner some insights into the narrower-versus-broader policy debate. Warning: I do not conclude that one approach dominates the other. In the spirit of full disclosure, I'll admit that as an older, technocratic, incrementalist who gives significant weight to opportunity costs, I'm congenitally more familiar and comfortable with narrow targeting. But as someone who has, for decades, watched increasingly concentrated wealth and power distort economic and particularly racial outcomes, I'm increasingly open to questioning my priors.

I'll say little about those who can't stomach debt cancellation. While I understand where they're coming from, I wouldn't let such resentment block useful public policy. Should the government not subsidize health coverage for those without it because the rest of us have long paid our premiums? Was the introduction of Social Security and Medicare unfair to those who had to retire without them? That's not saying student debt relief is useful public policy or that Warren's plan is the way to go. It's saying that the fact that the introduction of any public benefit may be viewed as unfair to those who won't receive it tells you little about the extent to which that benefit will improve social welfare.

Is college debt reduction good public policy?

Whether debt relief is good public policy and if so, how best to do it, is a more interesting question. The rationale for helping student borrowers is strong. First, K-12 education has long been viewed as a public good, meaning absent government support, the population would under-invest in it with negative economic, social, and political consequences. But, as I said in my earlier piece, 12 is no longer the right number for the high end of that range. Workplace skill demands have steadily increased, driving up the need for a more educated workforce (note that this is a different argument than the ubiquitous, and suspect, claims of skill shortages by many employers).

Second, college tuition (and the ancillary costs, like boarding and textbooks) has increased a lot faster than typical household income incomes (the BLS price index for college tuition and fees rose 63 percent, 2006-16, while nominal median income rose 22 percent). Yes, grants improve affordability, but at public four-year colleges, annual costs increased by $6,300 since 2000, while annual aid increased by less than half that amount. Meanwhile, states have significantly disinvested in higher education (the average state spent 16 percent less—inflation adjusted—per student on public colleges and universities in 2017 than in 2008).

At the same time, the return to college has also gone up and the evidence shows that for many students who complete their degrees, even with loans, college pays off. Still, these two facts—higher ed as a public good and the affordability challenges it poses for many families of limited means, especially for racial minorities—provides a rationale for helping at least some group of student borrowers. A third rationale is that the extent to which the historically large stock of student debt is a negative for the macroeconomy.

Here's how (my old Obama-era pal) James Kvaal, now the president of The Institute for College Access & Success, recently put it (italics added):

For college to be affordable, students must be able to both make ends meet while enrolled and successfully repay their loans after leaving school. Unfortunately, for many students, one or both of those goals are not possible today. Financial barriers still keep many students from earning college degrees and—while the returns to college are high for those who succeed— there is a crisis for the many students who struggle to repay their loans. A million students a year default.

For these reasons, various debt relief programs already exist, though they are, as Kvaal's comments suggest, insufficient. Few experts in this area of education policy view the status quo as adequate, and thus, we need to do more.

Critics of Warren's plan argue it is not progressive enough

And yet, many criticized Warren's plan for providing more debt relief than is necessary to too many debtors who don't need the help. That is, they judged the plan to be too generous and not progressive enough because too much debt cancellation goes to upper income borrowers.

The claim is reflected in numbers released both by Warren and outside analysts. An Urban Institute analysis finds that 32 percent of the cancelled debt would go to the bottom 40 percent while 45 would go to the top 40 percent (a Brooking analysis yields similar results). Warren's materials show that at least 80 percent of all borrower households up to the 80th percentile get full debt cancellation, though this share falls to about half of those in the top fifth.

Given that distribution, columnist David Leonhardt, who has long advocated for helping the neediest in their pursuit of higher ed, worries that the plan will help "a 24-year-old in Silicon Valley making $90,000" thereby confusing "the mild discomforts of the professional class with the true struggles of the middle class and poor."

To be clear, even by these numbers, because its top benefit ($50,000 applied to debt cancellation) begins to phase down at $100,000 of household income, the plan maintains some degree of progressivity (to which Leonhardt gives a nod) and racial equity. The Urban analysis finds that 56 percent of the debt relief goes to families in the bottom 60 percent, with incomes below $65,000. Warren's materials show total cancellation for about 90 percent of those with an associate degree or less compared to 25 percent of those with a professional degree or doctorate. Since student borrowing rises with income, and the plan cancels 40 percent of the outstanding debt of 75 percent of borrowers, the 60 percent it doesn't cancel is mostly held by higher-income families (above the plan's $250,000 cutoff) with high amounts of debt. Urban's analysis finds the plan disproportionately helps African-American borrowers (black households are 16 percent of all households, but they receive 25 percent of all cancelled debt).

Still, the plan's design could be tweaked so that more of its benefits would reach low versus higher-income borrowers. Because higher income families borrow more for college, lowering both the $50,000 forgiveness threshold—say, to $20,000—and more so, starting the phaseout lower—maybe at $60,000 instead of $100,000—would boost progressivity and lower the cost.

The challenge is that when you're cancelling student debt, because high-end households are more likely to borrow for college and to borrow larger amounts, it's hard to achieve high progressivity. That's one reason why many critics of the plan prefer income-based repayment options (where borrowers pay 10 percent of their disposable income to service their debt, which is forgiven after 20-25 years of such payments) and/or, as Leonhardt argues, "an enormous investment in colleges that enroll large numbers of middle-class and lower-income students."

Is the goal of college debt reduction to help low-income borrowers or to pushback on structural inequality?

Is targeting debt reduction to poorer households clearly the better policy choice in this space? The critics argument—a resonant one—is: in a world of limited resources, why aid "mild discomfort" when you can help those with "true struggles?"

But Warren is coming at the issue from a different perspective. Her purpose is not to parse these two groups. It is the more ambitious (and thus, more expensive and interventionist) goal of resetting the imbalances driven by the vast increase in wealth inequality. Her motivation comes from her oft-stated belief that concentrated wealth equals concentrated power, political influence, and the stripping of opportunities from broad swaths of Americans, most notably racial minorities, and not just the poor.

It is thus not incidental that her higher ed plan (which, as I discuss below, includes a lot more than debt relief), is financed by a tax on extreme wealththat hits the top 0.1 percent of wealth holders. The goal is to claw back some of this narrowly concentrated wealth to provide more opportunities for all the families who face some of costs of these extreme imbalances. No question, it will help some computer engineers and lawyers. But in so doing, the hope is that by reducing that engineer's debt burden, she will have the freedom to start her own business. A lawyer who benefits from her plan will have the economic space to shun the corporation in favor of public service law.

Viewed through that lens, the Warren plan is not designed to target debt relief to the least well-off. It is instead designed to return some measure of economic security and freedom of choice to 42 million people from across the income distribution who, by dint of their current debt burdens, face economic constraints that she believes public policy should address.

There's more to the plan, most importantly making two and four your public colleges tuition free. That's a whole other discussion, though it raises all of these same issues. Re progressive targeting, I've seen too few references to the fact that her plan also calls for $100 billion in higher funding for Pell Grants—the program Kvall called "the most important federal commitment to college opportunity." Given free tuition, these grants would pay non-tuition costs, which for many students outpace their tuition costs.

But none of that negates the opportunity costs invoked by this and other plans with such broad scope. A dollar spent on a $100,000 household is one that isn't spent on a $20,000 household, and it's undeniable that the latter needs more help than the former, especially when we consider those students whose upward mobility is most elastic to a quality, higher education are the ones least able to afford it.

But it is also undeniable that, in the face of levels of inequality that we haven't seen in this country since the 1920s (which, for the record, did not end well), it will take more than narrowly targeted corrections to reset the balance of power and opportunity in America. I don't know if this or any other big idea is part of the solution. Also, I've ignored politics, which I've argued elsewheremay be more conductive to targeted incrementalism than sweeping reforms. But those of us who seek economic and racial justice must entertain the possibility that relative to the sorts of ideas we've long promoted, it may take a policy agenda that's bigger, more disruptive, and more ambitious, to start to repair the damage.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

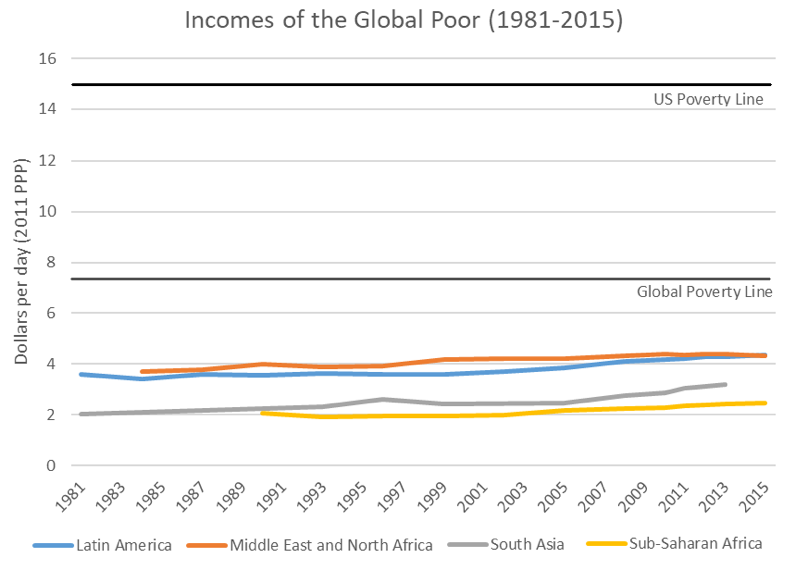

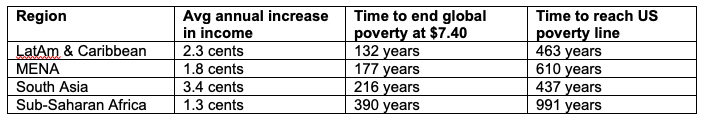

At this Rate, It Will Rake 200 Years to End Global Poverty [feedly]

https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/29/04/2019/rate-it-will-rake-200-years-end-global-poverty

During the debate about global poverty that erupted earlier this year, one fact kept getting repeated: maybe poor people's incomes haven't increased enough to lift them out of actual poverty (grudgingly admitted), but at least they've been rising. For those who seek to defend neoliberal globalization, this fact has become a precious touchstone.

While it is true that the average incomes of poor people have increased since 1981, there are two crucial caveats to this that we need to pay attention to.

1) First, the increase has not been steady. Indeed, there have been long periods over the past few decades where the average incomes of the global poor (those living on less than $7.40 per day, the minimum necessary for decent nutrition and normal life expectancy) didn't rise at all, and quite often actually fell. Here are a few examples:

In Latin America and the Caribbean, the average income of the poor fell after 1981 and didn't recover its previous level until two decades later.

In the Middle East and North Africa, the average income of the poor fell after 1990 and didn't recover its previous level until a decade later.

In South Asia, the average income of the poor fell after 1996 and didn't recover until 2008.

And in Sub-Saharan Africa the average income of the poor declined after 1981 and didn't recover until more than two decades later, in 2005.

Crucially, these periods of decline and stagnation happened almost entirely during the 1980s and 1990s, as neoliberal structural adjustment programs were imposed across the global South. In other words, the imposition of Washington Consensus capitalism during this period not only caused the number and percentage of poor people to rise (as I have described elsewhere), it also caused the incomes of the poor to decline and stagnate.

2) Second, the increase that has happened has been at an astonishingly slow pace. Since 1981 poor people's daily incomes have increased by only about 2 cents per year, on average.

At this rate it will take around 200 years to end global poverty at $7.40 per day, and 500 years to end poverty at the US poverty line of $15 per day.

The graph above is based on World Bank poverty data. I've calculated the total poverty gap per region per year (i.e., the amount of additional income it would take to bring everyone above the poverty line of $7.40 per day), divided this by the number of poor people in each year to get the average distance that poor people live below the poverty line, and then subtracted this from $7.40 to show average income.

Keep in mind that this figure counts not only income but also consumption. So if a person is living on $2 per day, that includes not only the cash they might earn from wages, but also the value of food they grow themselves, and anything they might scavenge or receive as gifts for household consumption. And all of this is valued in terms of purchasing power in the United States. So $2 is what that amount of money would buy in the US in 2011; barely anything, basically. Not even enough to cover basic food needs.

What is more, these results overstate the incomes of the poor because the World Bank's methodology doesn't account for the fact that poor people spend a disproportionate amount of their income on food.

Here's what the World Bank data reveals:

And remember: these are the people who render the majority of the resources and labour that keep the global economy going. What they get in return for that is literally pennies.

Those like Gates and Pinker who so adamantly defend the status quo of the global economy – this is what they are defending. That the incomes of the poor should grow by 2 cents per year, ensuring that poverty will be with us for hundreds of years to come.

This is a striking position to take, when you consider that poverty could be ended right now, forever, simply by shifting $6 trillion of existing global income to the poorest 60% of humanity. This would be enough to lift every human on the planet above the $7.40 line.

For perspective, the richest 1% capture more than $18 trillion each year in income, according to the World Inequality Database. In other words, we could tax the 1% a mere third of their income to put an end global poverty, and still leave them with an average income of $175,000 per year.

This is just a thought experiment, of course; to me a better approach is to change the rules of the global economy so that the world's majority can claim a fairer share of the yields they produce in the first place, as I argue in The Divide. But the point is clear: global poverty today isn't natural or inevitable, it is an artifact of the very same policies that have been designed to siphon the lion's share of global income into the pockets of the rich.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

West Virginia GDP -- a Streamlit Version

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.

-

John Case has sent you a link to a blog: Blog: Eastern Panhandle Independent Community (EPIC) Radio Post: Are You Crazy? Reall...

-

---- Mylan's EpiPen profit was 60% higher than what the CEO told Congress // L.A. Times - Business Lawmakers were skeptical last...

-

via Bloomberg -- excerpted from "Balance of Power" email from David Westin. Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the late...