https://urpe.wordpress.com/2019/03/20/is-mmt-america-first-economics/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

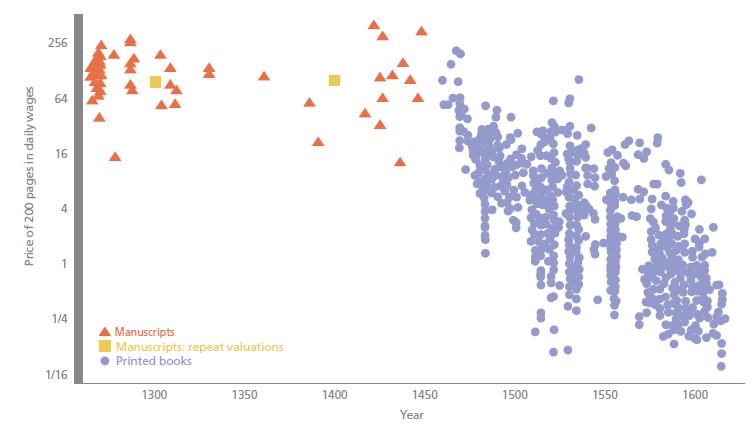

"Printing was not only a new technology: it also introduced new forms of competition into European society. Most directly, printing was one of the first industries in which production was organised by for-profit capitalist firms. These firms incurred large fixed costs and competed in highly concentrated local markets. Equally fundamentally – and reflecting this industrial organisation – printing transformed competition in the 'market for ideas'. Famously, printing was at the heart of the Protestant Reformation, which breached the religious monopoly of the Catholic Church. But printing's influence on competition among ideas and producers of ideas also propelled Europe towards the scientific revolution.While Gutenberg's press is widely believed to be one of the most important technologies in history, there is very little evidence on how printing influenced the price of books, labour markets and the production of knowledge – and no research has considered how the economics of printing influenced the use of the technology."

Previous economic research has studied the extensive margin of technology diffusion, comparing the development of cities that did and did not have printing in the late 1400s ... Printing provided a new channel for the diffusion of knowledge about business practices. The first mathematics texts printed in Europe were 'commercial arithmetics', which provided instruction for merchants. With printing, a business education literature emerged that lowered the costs of knowledge for merchants. The key innovations involved applied mathematics, accounting techniques and cashless payments systems.It is impossible to avoid wondering if economic historians in 50 or 100 years will be looking back on the spread of internet technology, and how it affected patterns of technology diffusion, human capital, and social beliefs--and how differing levels of competition in the market may affect these outcomes.

The evidence on printing suggests that, indeed, these ideas were associated with significant differences in local economic dynamism and reflected the industrial structure of printing itself. Where competition in the specialist business education press increased, these books became suddenly more widely available and in the historical record, we observe more people making notable achievements in broadly bourgeois careers.

The Green New Deal is desperately needed, and arguing about a price tag is like Henry Ford wondering if the country will be able to afford his brand new automobile. With the introduction of a House Resolution by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-New York) and Sen. Edward Markey (D-Massachusetts), a debate has surged across the country on the affordability of the Green New Deal. The sheer distraction of the affordability discussion is enough to ensure that very few people will pay attention to what is really at stake. For when the bigger fish eat up this little fish we will need to remember how we got here and what matters most. As the bright young critics have quickly observed, the Green New Deal could hardly be too green. Time is wearing thin and we need to make haste.

But there can be no greening that abstracts from political economy realities and while the tug of war taking place in the media at the moment is all about the so-called economy-of-it-all, there is next to no analysis on the political constraints of sustainably embarking on another New Deal when the first one withered away long ago. After World War II, the ambition of a nationwide spending program was quickly replicated on an international scale as the country rightly observed that in a vacuum the United States would be hard pressed to expand its economy and that what it needed to make large projects like the Tennessee Valley Authority which introduced unprecedented stimulus, sustainable in the long run was the integration of the United States capital stock's capacity to produce output with a global trend of expanding markets. Unless the United States comes to terms with the global characteristics of its (not to mention everyone else's) economy, we will all the rest of us more than likely pay the brunt of another American adventure. How does America exact these payments? By imposing continued low growth trajectories, low wage growth, contractionary balance of payments adjustments, and what Keynes called "forced exports", which is basically what we call today narrow and specialized development: all opposed to diversification.

If the truth be told, the heavy handed unilateral approach of the United States renders the rest of the global economy akin to something that can be thrown off the back of a train to pay for America's projects. By America's choice, the world has pursued a most exclusionary development path with low growth trajectories being imposed on much of the world's population, even Europe's, to ensure the political dominance of one country, which itself is willing to sacrifice the high growth it could enjoy itself along with the rest of the world through inclusive multilateralism. The decision for this can be traced back to 1951, two years after what has sometimes been referred to as 'the Kaldor Report' was discussed at ECOSOC. This would be the last serious consideration for institutionalizing Full Employment at the international level, which is to say that it was the last serious effort to institutionalize multilateral trading in support of an expansive global economy.

It is this author's opinion that this would have required the mediatory institutions sought by John Maynard Keynes. As he confided to his compatriots, "the difficulties are thoroughly shirked" (Keynes, 1980: 325), "The two Institutions have become different from what we were expecting." (Ibid: 232) These statements commence a long line of lament by those working in the official institutions of international development. Contrary to the less than exhaustive investigations by the most powerful parties involved in the post-War framing, certain extensive and earnest treatments of the rationale for full employment have been attempted. The tensions that constituted the political sequence which framed the post-War economic institutions were all but resolved. They can fruitfully be resubmitted to thought.

The ability of the USA to pay for the Green New Deal is inherently connected to its relation to the global economy, at the broadest level. It can flounder on uninviting seas and when needed release its fury spanking the waves after Xerxes, or it can take stock of what Keynes called the "high ways of the real world", and awake to the rough realities it has imposed around the globe. To the extent that America's low growth trajectory displaces demand in the global economy— or to the extent that its low wage growth policy is the only way it manages to insert itself into the global economy, its longstanding policy of aggressive bilateralism will continue. The world's economies are intimately interlinked and what is needed is not an American scheme but a global one — which picks up the multilateralism that once wanted to be born.

Shaun Ferguson has worked in development economics at various United Nations agencies including UNCTAD, ESCWA and UNSCO since 2002. He has a doctoral degree in Economics at the New School for Social Research.

The extent to which the navies and trading fleets of the great European sea-borne empires of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries shaped the industrial development of western Europe has always been one of the most fiercely-debated and unsettled topics in economic history. That European expansion in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries were catastrophes for the regions of west Africa that were the sources of the slave trade; for the Amerindians of the Caribbean; for the Aztecs, Incas, the mound-builders of the Mississippi valley; and for the princes of Bengal and others who found themselves competing with the British East India Company in the succession wars over the spoils of India's Moghul Empire—that is not in dispute.

But how much did pre-industrial trade and plunder affect European development? That is not so clear.

It is clear is that even at the end of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century trade not in luxuries but in staples had begun to profoundly shape history. For the first time transoceanic trade mattered not just for a ruling elite but for an economy as a whole. The export of cotton from the American South and had mattered. Without the appetite of British and New England factories for cotton and the power to ship ginned cotton to them cheaply, the slaves of the American South in 1860 would have been what they were for George Washington in the 1790s: a quarter of your wealth that you were willing to free, at least upon your death, because it was the right thing to do. By contrast, for Jefferson Davis it wasn't his land but rather his slaves that were three-quarters of his wealth—and so the U.S. Civil War of 1861-5 came.

Early-nineteenth century cotton showed what late-eighteenth century sugar had prefigured. The export of sugar from the Caribbean islands and Latin America (and also tobacco, tea, coffee, chocolate, and so forth) meant that European agriculture did not have to grow nearly as much flax or raise as much wool or produce as many calories. It provided an extra edge to the British economy: as if there was perhaps one additional ghost worker who did not have to be fed or paid alongside every ten.

That, from the perspective of 1870, was what the expanded intercontinental division of labor and the higher productivity that resulted from it had done up to that point.

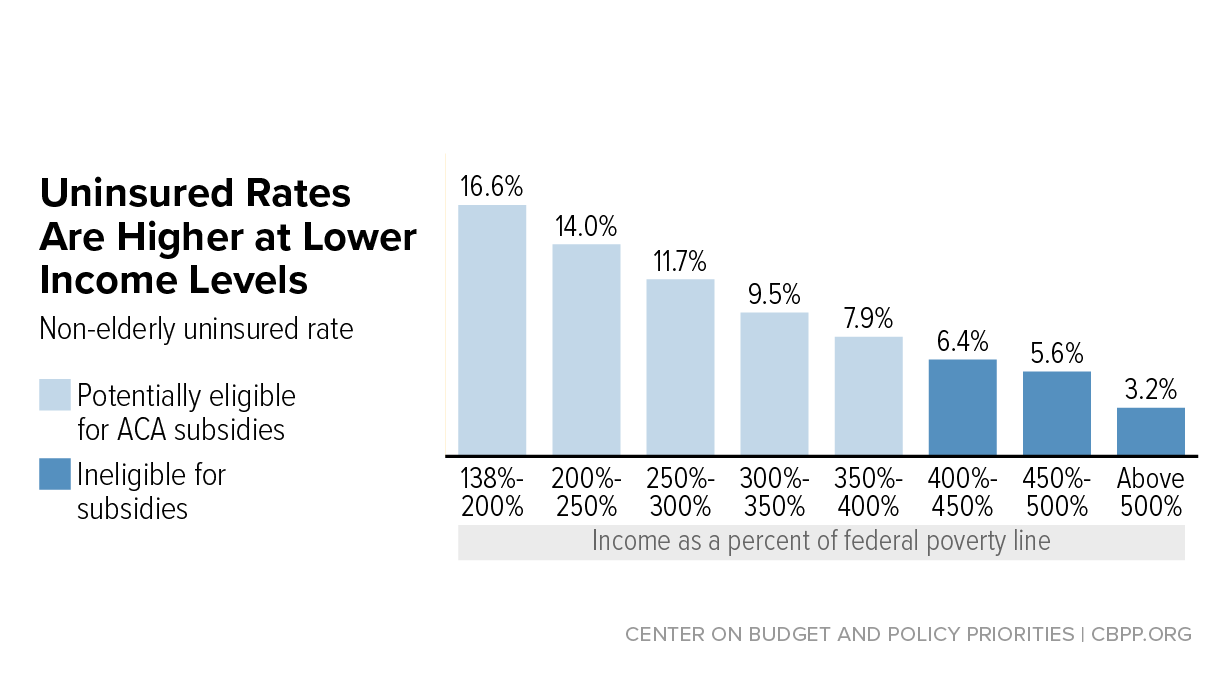

Nine years after President Obama signed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on March 23, 2010, the uninsured rate remains at a historic low and more than 20 million people have gained coverage — but about 30 million non-elderly people are still uninsured. Several new CBPP analyses examine the uninsured and identify policies to continue expanding coverage and making coverage and health care more affordable.

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.