Tuesday, December 4, 2018

Progress Radio:The Ideal Became Real: A RIOT of TRUTH on the Progress Diner Radio Show -- Drunks Delight #2

Blog: Progress Radio

Post: The Ideal Became Real: A RIOT of TRUTH on the Progress Diner Radio Show -- Drunks Delight #2

Link: http://progress.enlightenradio.org/2018/12/the-ideal-became-real-riot-of-truth-on.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Olivier Blanchard : The French "Yellow Vest" Movement and the (Current) Failure of Representative Democracy : "Go back ... [feedly]

https://www.bradford-delong.com/2018/12/olivier-blanchard-_the-french-yellow-vest-movement-and-the-current-failure-of-representative-democracyhttpspii.html

Olivier Blanchard (PIIE)

December 3, 2018 1:00 PM

Photo Credit: REUTERS/Stephane Mahe/File Photo

Images of gilets jaunes in France—so named for the yellow vests they wear—have flooded news broadcasts in recent weeks. To trace the deep roots of their protests, one has to go back to the end of communism and the failure of central planning as an alternative to the market economy.

Up until then, central planning represented for some the hope that there was a more humane alternative to capitalism, one in which there was less inequality and less insecurity. Politics could be organized from left to right, along mostly economic lines, with central planning at one end and the market economy at the other. The communist party stood at one extreme, then the socialist party, then (rather timidly in France) the more market-oriented center right parties at the other end. Political life was fairly well organized, and parties and unions played their role as conduits for their constituency's preferences.

However, with the end of communism, it became clear that there was no alternative, only a muddle between market intervention and free markets. So long as growth was strong, and all boats were indeed lifted, the problem was manageable. Then growth slowed down, and inequality and insecurity became more salient, with no simple solution in sight.

The center-right and center-left parties tried their best to manage, but their efforts were not good enough. Sarkozy tried reforms but failed. Hollande, his successor, had a more realistic agenda but did not achieve much. Unemployment remained high and taxes increased. People increasingly felt that the traditional parties did not improve their lot, nor did they represent them.

Then came Macron, who correctly pointed out that the left/right distinction did not make much sense anymore, and he won by occupying the large middle. In doing so, he tore the traditional center left and right parties to pieces, leaving only the extreme right and the extreme left as alternatives.

In the process, he may have made the political system worse. As the economy has not improved much yet, people, unhappy with the lack of results, do not have the traditional parties to turn to. Some have joined the extreme left or the extreme right. More have become skeptical of any representation, be it parties or unions, and have taken to the streets. Thus the gilets jaunes was born, a spontaneous and unorganized response, a form of direct democracy.

But unorganized direct democracy does not work. In a country of 65 million people, ancient Athens' agora-style democracy cannot work. We have seen this in the last three weeks. There is no coherent voice or message emerging from the movement: The state cannot provide more public services and simultaneously lower taxes. In the streets, the movement cannot avoid being hijacked, to its dismay, by anarchists or vandals. It is going nowhere.

The challenge to the government and the political class is immense. If I am right, the sources of the problem are old and deep. The government must convince people that it is hearing them, while making clear that it cannot deliver the impossible. And the opposition must avoid playing with fire: Unorganized anger can lead to chaos.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Excavating Layers of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 [feedly]

http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2018/12/excavating-layers-of-tax-cuts-and-jobs.html

Michael J. Graetz writes the "Foreword—The 2017 Tax Cuts: How Polarized Politics Produced Precarious Policy." He touches on a number of the themes mentioned in the two papers by Joel Slemrod and Alan Auerbach in the"Symposium on the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act" that appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives: yes, the US corporate taxation needed both lower rates and more sensible treatment of multinational companies, but in many ways the new tax bill created a muddle--and a muddle that will lead to substantially higher budget deficits. Here's a flavor of Graetz (footnotes omitted throughout):

"The Democrats' complaints about the law's reduction in the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% ring hollow. Democrats themselves had long realized that the U.S.'s exceptionally high corporate tax rate in today's global economy—with highly mobile capital and intellectual property income—invited both U.S. and foreign multinational companies to locate their deductions, especially for interest and royalties, in the United States, and to locate their income in low- or zero-tax countries. This is obviously not a recipe for economic success. Both before and after the legislation, Democrats urged a corporate tax rate of 25% to 28%; meanwhile, Donald Trump asked for a 15% rate.So, even if Democrats had been involved in the legislative process, the 21% rate that we ended up with would be in the realm of a reasonable compromise. ... [A] significantly lower corporate rate has been long overdue, and raising it would be a mistake. If Democrats are unhappy with the distributional consequence that a corporate tax cut will benefit high-income shareholders, the appropriate remedy––given the mobility of business capital, businesses' ability to shift mobile intellectual property and financial income to low-tax jurisdictions, and the challenges of intercompany transfer pricing––is to increase taxes at the shareholder level, not to increase corporate tax rates. ...

Congress's greatest challenge in crafting this tax legislation was figuring out what to do about the international tax rules. ... Congress confronted daunting challenges when deciding what rules would replace our failed foreign-tax-credit-with-deferral regime. There were essentially two options: (1) strengthen the source-base taxation of U.S. business activities and allow foreign business earnings of U.S. multinationals to go untaxed; or (2) tax the worldwide business income of U.S. multinationals on a current basis when earned with a credit for all or part of the foreign income taxes imposed on that income. Faced with the choice between these two very different regimes for taxing the foreign income of the U.S. multinationals, Congress chose both. ...

No doubt analysts can find provisions to praise and others to lament in this expansive legislation, but we should not overlook its most important shortcoming: its effect on federal deficits and debt. ...

Under the 2017 tax law, the federal debt held by the public is estimated to rise to more than 96% of GDP by 2028, and this does not count the omnibus spending bill signed in 2018 by President Trump. ... If the current policy levels of taxes and spending are maintained, total deficits over the next decade will approach $16 trillion, with deficits greater than 5% of GDP beginning in 2020. By 2028, current fiscal policy will produce deficits of more than 7% of GDP annually. This is unsustainable. ... The budget legislation of the 1990s, along with the economic growth unleashed by the information technology revolution of the late 1990s, completely eliminated the projected deficits by the year 2000 and produced a federal surplus for the first time since 1969. Indeed, the budget surpluses projected by the Congressional Budget Office at the beginning of this century were so large that, in March 2001, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan told Congress that the federal government would soon pay off all of the national debt and would have to begin investing its surplus revenues in corporate stocks, a prospect he abhorred. The good news is that this problem has been solved.

I was also struck by the essay by Linda Sugin, "The Social Meaning of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act." Sugin describes the social values that seem to underlie the provisions of the TCJA. She writes:

This Essay discusses five American priorities and values revealed by the TCJA:

1. The traditional family is best;

2. Individuals have greater entitlement to their capital than to their labor;

3. People are autonomous individuals;

4. Charity is for the rich; and

5. Physical things are important.

The TCJA's distributional effects dovetail with these values. ... First, traditional families with a single working spouse and a stay-at-home spouse are disproportionately prosperous, so subsidizing that family model reduces progressivity. Second, access to capital increases with affluence, so a greater entitlement to investment income favors taxpayers who enjoy that affluence. Third, valuing individual autonomy is consistent with robust individual property rights, and less consistent with high levels of taxation for shared community purposes. Fourth, favoring the charitable giving of the rich allows them tax reductions not available to others, and sends the message that philanthropy substitutes for tax paid. Fifth, prioritizing physical assets favors individuals are able to invest in such assets and underrates the important value that workers contribute to prosperity. Critics of the legislation concerned about the law's reallocation of tax burdens down the income scale and its projected budgetary deficits must focus more on these embedded priorities.

Of the other three papers, two papers dig into details of the changes in the international corporate tax regime, while the other argues that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will push firms away from the use of debt financing--and thus toward alternative types of financing--with implications that are not yet clear.

Rebecca M. Kysar discusses "Critiquing (and Repairing) the New International Tax Regime."

"In this Essay, I address three serious problems created—or left unaddressed—by the new U.S. international tax regime. First, the new international rules aimed at intangible income incentivize offshoring and do not sufficiently deter profit shifting. Second, the new patent box regime is unlikely to increase innovation, can be easily gamed, and will create difficulties for the United States at the World Trade Organization. Third, the new inbound regime has too generous of thresholds and can be readily circumvented. There are ways, however, to improve upon many of these shortcomings through modest and achievable legislative changes, eventually paving the way for more ambitious reform. These recommendations, which I explore in detail below, include moving to a per-country minimum tax, eliminating the patent box, and strengthening the new inbound regime. Even if Congress were to enact these possible legislative fixes, however, it would be a grave mistake for the United States to become complacent in the international tax area. In addition to the issues mentioned above, the challenges of the modern global economy will continue to demand dramatic revisions to the tax system."Susan C. Morse raises implications about International Cooperation and the 2017 Tax Act.

"Some have criticized the 2017 Tax Act for lowering the corporate tax rate. This Essay argues instead that Congress deserves credit for bringing the U.S. rate in line with other OECD countries, potentially saving the corporate tax by establishing a minimum global rate. ... There is a silver lining for the corporate income tax in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. This is because the Act's international provisions contain not only competitive but also cooperative elements. The Act adopts a lower, dual-rate structure that pursues a competitiveness strategy and taxes regular corporate income at 21% and foreign-derived intangible income at 13.125%. But the Act also supports the continued existence of the corporate income tax globally, thus favoring cooperation among members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Its cooperative provisions feature the minimum tax on global intangible low-taxed income, or GILTI, earned by non-U.S. subsidiaries. Another cooperative provision is the base erosion and anti-abuse tax, or BEAT. The impact of the Act on global corporate income tax policy will depend on how the U.S. implements the law and on how other nations respond to it."Robert E. Holo, Jasmine N. Hay and William J. Smolinski discuss issues of corporate leverage in "Not So Fast: 163(j), 245A, and Leverage in the Post-TCJA World."

"The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will require large multinational corporations to reevaluate the use of debt in their acquisition and corporate structures. Changes to the Tax Code brought about by the Act have reduced incentives to use debt in these contexts. These changes may require practitioners to identify new approaches to financing acquisitions and will necessitate reevaluation of current capital structures used by large multinational entities. ...

"In other words, is it a good idea to dampen the worldwide preference for debt in capital structures? Is there a problematic preference for debt that needs fixing in the first place? It is likely too early to make that call given the potential number of unintended consequences that my result under the new law. ... By changing the rules of the game, the IRS has effectively changed the inputs to that modeling exercise. It remains a complicated question whether, holistically, business entities carry excess debt relative to equity; but it is certainly the case that a new set of rules which, on their face, appear to favor equity over debt, may very well cause those modeling exercises to produce an output that suggests a shift in debt-equity preferences is in order."

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Sanders-Khanna Bill Would Stop Monopoly Drug Pricing in the US [feedly]

http://cepr.net/publications/op-eds-columns/sanders-khanna-bill-would-stop-monopoly-drug-pricing-in-the-us

Dean Baker

Truthout, December 3, 2018

Debates on economic policy are often far removed from reality. Nowhere is this truer than in the case of prescription drug prices.

In the United States, we pay high drug prices because the government gives pharmaceutical companies patent monopolies, where it threatens to arrest anyone that sells a drug in competition with the patent holder. As a result, drugs often sell for prices that are several thousand percent above their free market price.

Incredibly, in debates on drug prices, these monopoly prices are routinely described as being the result of the free market, turning reality completely on its head. The people who want to lower drug prices are then said to be trying to interfere with the free market, which we are all supposed to think is a bad thing to do.

This is one of the reasons why a new bill to lower drug prices by Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Ro Khanna is so brilliant. The bill is actually lowering drug prices by using the power of the market, making it clear that the proponents of high drug prices are the ones who want the government to interfere with the market to keep drug company profits high.

The bill would effectively end the patent monopoly for any drug where the price in the United States is above the median of the prices charged in the next seven largest wealthy countries. This is likely to mean a reduction in the price of most brand drugs by around 50 percent.

The reason is that, while other countries also grant patent monopolies and related protections to drugs, they don't allow the manufacturers to exploit these monopolies to the same extent as in the United States. They have some sort of price negotiation with drug companies, which is intended to place a limit on the price that can be charged when people's health or life is at stake.

In effect, the Sanders-Khanna bill imports the price negotiation process put in place by these other countries. Drug companies will have a strong incentive to set their price below the median of the seven benchmark countries. If they charge a higher price, they effectively lose their patent monopoly. They could still make some money off of licensing fees charged to generic producers, but this would be a small fraction of what they would make from having a patent monopoly.

Another nice feature of the Sanders-Khanna bill is that it would lower drug prices for everyone, not just Medicare patients. There have been a number of bills introduced in recent years that have been designed to reduce the cost of drugs for people in Medicare. While lower drug prices for people enrolled in Medicare would be good, we should be looking to reduce our drug prices across the board. There is no reason people in the United States should be paying so much more than everyone else.

The industry's response will be to whine that if they charged lower drug prices they won't be able to finance the development of new drugs. There is a grain of truth to this, but only a grain. The industry will collect roughly $440 billion (2.2 percent of GDP) in revenue this year from sales in the United States alone. It spends around $70 billion on research. This is less than one-sixth of the money it pulls in.

Certainly, if we did bring spending down to the levels in other wealthy counties it would lead to somewhat less research, but the question is the size of the falloff in research. After all, by giving another $1.5 trillion to corporations over the next decade, the Trump tax cut will almost certainly lead to some additional investment, but the question is how much. The evidence to date with the tax cut is that we are seeing very little payoff in the form of higher investment. Similarly, the additional revenue from unchecked patent monopolies is likely to translate into little by way of additional research into developing new drugs.

Ultimately we should be looking to more modern and efficient mechanisms than patent monopolies for financing drug research. The government already spends almost $40 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health. If we paid for the research up front, then all new drugs could be sold at their free market price from day one, saving us close to $400 billion a year. In that world, prescriptions would be $20 or $30 a piece, not hundreds or thousands of dollars.

But for now, the Sanders-Khanna bill is a huge step forward in making drugs affordable. And, it does it by using the market forces, a prospect that is very scary to the pharmaceutical industry.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Vast Majority of Those Losing Coverage From Medicaid Waivers Will Be Uninsured [feedly]

https://www.cbpp.org/blog/vast-majority-of-those-losing-coverage-from-medicaid-waivers-will-be-uninsured

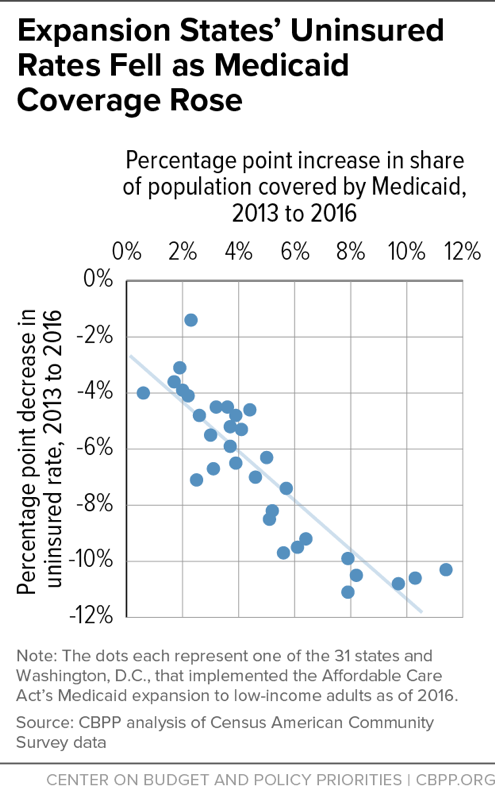

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Administrator Seema Verma says the large Medicaid coverage losses under Arkansas' waiver may not be translating into higher uninsured rates.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Monday, December 3, 2018

Asia Times: The China trade reality show [feedly]

http://www.atimes.com/article/the-china-trade-reality-show/

or at least a month, there has been no doubt that Presidents Donald Trump and Xi Jinping would agree to agree at the Buenos Aires summit. The threats, remonstrations and hints of high officials were for the most part scripted. Buenos Aires was less negotiation than reality show.

When the dust settles, America and China will have a deal that allows Trump to claim victory and allows China to become the world's dominant

Two things changed to bring America and China back to negotiations.

First, Trump learned that he was in the position of the Lord High Executioner in Gilbert and Sullivan's "Mikado," that is, "he can't cut off another's head until he's cut his own off." Trade war with China contributed to the correction in the S&P 500, which lost 10% peak-to-trough through last Wednesday. It also produced so much uncertainty about the future of supply chains that capital investment plunged around the world, as I reported November 30.

If Trump made good on his threat to impose tariffs on all Chinese imports, including most of American purchases of consumer electronics, the impact on household budgets would have been severe. Trump wants a second term, and trade war risked a recession just before the 2020 elections.

Second, China concluded that Trump wants to look like a winner, and decided to give him what he wanted. Senior advisers to the Chinese government explained this to me last October. The new Chinese consensus holds that the world's largest country can afford to be patient, concentrate on raising productivity and per capita income, and forego bragging rights about its growing economic power. As I wrote from Beijing:

"The United States during the 19th century did not attempt to impose its will on other countries, [one advisor] noted. Only after the Second World War did the United States act like a major power. China, he concluded, will have to take a more modest role in world affairs 'until 2035, when it will be a much more powerful country.'"

There is a coterie of advisers in and around the Trump Administration that appeared to believe that trade war would damage China's economy so severely as to destabilize the rule of Xi Jinping. For years, the American consensus held that China's opening to the world economy inevitably would lead to a democratic transformation of this ancient empire. When that failed to happen, the same advisers argued that the Chinese system must collapse of its own weight because (as they believe) the American way of doing things is the only right one.

Among the president's senior staff only National Security Adviser John Bolton takes this sort of talk seriously. Before taking office, Bolton advocated stronger support for Taiwan against the mainland. The resounding victory in Taiwan's local elections last month of the Kuomintang, a party that eschews calls for independence and supports closer ties with the mainland, took this idea off the agenda.

It is unclear to what extent the revolt of America's allies influenced Washington's thinking. Beijing showed its seriousness about opening its financial industry to foreign firms last week by offering a license to the German insurance giant Allianz. There will be something of a gold rush of global firms into the Chinese market, and American companies do not want to be at the end of the queue.

What the US and China actually will negotiate during the next 90 days will include the following:

1) More US exports to China, especially LNG. China might invest in LNG facilities on the US West Coast to increase capacity.

2) An intellectual property agreement dictated by the United States. China will crack down on technology theft, at least where official institutions are concerned, and leave Apple and Qualcomm to sue each other over patent infringement.

3) Further opening of the Chinese market to US trade and investment.

4) The abandonment of the "Made in China 2025" slogan, although the same investments will proceed with less fanfare.

None of this will do America much good in the long run. Trump asked for the wrong things and Xi agreed to concede them.

According to industry experts, China is spending upwards of US$50 billion for semiconductor fabrication each year, compared to less than US$5 billion in the US. Some experts believe that the fabrication of semiconductors will come to an end in the US within five years.

Asian companies will dominate key new technologies, including 5G mobile broadband, which is critical for the so-called Internet of things. American media reported today that Apple will wait until some unspecified future date to offer handsets that use the 5G technology. China's telecommunications giant Huawei, which now sells more handsets than Apple, is trying to position itself as the leader in the field. So is South Korea's Samsung.

America, in short, is losing ground not only in semiconductor and other high-tech electronic production, but also in design.

When America really was great back in the 1980s, federal R&D (overwhelmingly defense and NASA) amounted to 1.2% of GDP, versus just 0.7% today. Most of the R&D budget has been diverted to things like climate change, or status-quo weapons systems like the F-35. As matters stand, nothing will prevent China from becoming the dominant world economy by 2035 except, of course, missteps by China itself.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

ABC Sitcom The Conners: The Struggle is Real [feedly]

https://workingclassstudies.wordpress.com/2018/12/03/abc-sitcom-the-conners-the-struggle-is-real/

Life expectancy for Americans has fallen to an average of 78.6 years. This is a drop from the most recent estimates—indicating a downward trend that is virtually unheard of in Western countries. A report just released from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls this "a disturbing result not seen in the US…since 1915 through 1918, which included World War I and a flu pandemic." The report blames the downward trend on increases in opioid abuse, suicide, and diabetes.

So perhaps it is fitting that when ABC debuted The Conners, a spinoff from last year's canceled Roseanne, the writers decided to kill off Roseanne Conner by having her succumb to an opioid addiction—an addiction so secret that even her husband, Dan (John Goodman) was shocked when his daughters started unearthing random bottles of pain pills around the house after Roseanne's death.

The real life Roseanne Barr is still very much alive, as she reminded her fans when The Connors debuted in mid-October, tweeting, "I'm not dead, b*&%#es." But it was a tweet last May that killed Barr's tenure at ABC. She tweeted about President Obama's close advisor, Valerie Jarrett: "Muslim brotherhood & planet of the apes had a baby=vj." At first Barr blamed the tweet on the sleep aid, Ambien, and then she claimed that didn't know Jarrett was African American. Finally, she apologized: "to Valerie Jarrett and to all Americans. I am truly sorry for making a bad joke about her politics and her looks. I should have known better. Forgive me—my joke was in bad taste." But the damage was done. ABC promptly canceled Roseanne, calling Barr's tweet "abhorrent, repugnant, and inconsistent with our values."

Sara Gilbert, who plays Roseanne's daughter Darlene, and Goodman scrambled to find a way to keep the show alive. Indeed, the Roseanne reboot was Gilbert's idea in the first place. They were also concerned about the ability of the hundreds of people employed by the sitcom, in front of and behind the camera, to keep their jobs.

Ironically, perhaps, some have argued that The Conners is just as good—and maybe even better—than Roseanne. The show was always an ensemble piece, and every actor associated with the reboot has remained. Even better, D.J.'s (Michal Fishman) African American wife, who last spring was off camera fighting in Afghanistan, is now back from the war (Maya Lynne Robinson), and there are delightful cameos by Johnny Galecki as Darlene's ex-husband, Matthew Broderick as Jackie's pompous Halloween date, and Jay R. Ferguson (Peggy's bearded coworker from Mad Men!) as Darlene's new boss at a tabloid newspaper.

Michael Schneider writing for Indiewire suggests that without the distraction of Roseanne Barr's politics the show can go back to doing what it did so well in the 1990s: chronicling the woes of the working class. The Conners struggle with many problems familiar to working-class families: the grief from losing someone to opioid addiction, the additional loss of Roseanne's income, alcoholism, being fired, being underemployed, being forced to work in crappy service industry jobs because nothing else is available, blue collar jobs that suck, dicey sexual situations in the workplace, and a threadbare house that is falling apart and which has to hold several generations because of finances. The Conners also face less class-specific problems of tween sexuality, teenage sex, divorce, religion, politics, and a multi-racial family.

One of the most interesting consequences of the Roseanne reboot, its subsequent cancellation, and its rebirth as The Conners is that television critics are talking about class on television. These discussions fall into two oddly contradictory threads. Some argue that television has never properly addressed class, arguing, as Pepi Lesteinya did in Class Dismissed: How TV Frames the Working Class, that television has either long ignored, mocked, or derided the working class in its portrayals. The other thread, which seems to belie the first, is that in the good old days television represented the working class with love, but that now those days are gone.

The truth is more complicated than either of these claims.

First, working-class people have always been featured on network television in greater numbers than we have been able to see as scholars, in part because there are simply too many hours to count, watch, and apprehend. From my own research, I can assert that 1950s television was weird, heterogeneous, ethnically and racially diverse, full of working-class characters and themes, and ideologically diverse as well. While this is not a view in the scholarly mainstream, I have allies for this argument in the scholars who contributed to The Other Fifties: Interrogating Mid Century Icons, and, especially, Horace Newcomb's chapter, "Meaningful Difference in 50s Television."

Despite the seeming scarcity of working-class themed television comedies, many such shows have been at the center of a canon of the most watched and re-watched series in television history. The 1950s offered The Honeymooners and The Life of Riley, game shows like Queen for a Day, and variety shows featuring diverse casts such as The Milton Berle Show and The Red Skelton Show. The 1960s and 70s brought dozens of television series about public sector workers (nurses, teachers, cops, and fire fighters) and classics like All in the Family, Sanford and Son, Maude, and Laverne and Shirley. Don't forget the longest running TV series in history, The Simpsons or more recent series such as Two Broke Girlsand Superstore. Across these eras, working-class characters, working-class writers, and actors from working-class backgrounds have always been a core staple of the small screen. A quick visual for this comes from Vulture's timeline of working class sitcoms on network television.

Despite all this attention to the working class, one thing is for sure: television is bad at class struggle. On rare occasions, such as with the 1990s drama WWII era Homefront (1991-1993), unions are portrayed with dignity and realism, but for the most part television either ignores or distorts class conflict. On the other hand, the most consistent theme of most working-class sitcoms, including The Conners, is that it is a struggle to be working class.

In an op-ed last week David Brooks mused about the decline in life expectancy for Americans, concluding that since the economy is currently going gangbusters, that the only thing that can explain the uptick in opioid deaths and suicides among working-class Americans is some strange brew of economics, philosophical rot, and moral decay. But Brooks is wrong. Whatever the GDP might indicate, the American economy has been in decline for working people for a long time—even more so since the financial collapse of 2008. There is no single state in the US in which a minimum wage job can afford a worker a two-bedroom apartment. Inequality is more pronounced than in any time in US history. African American poverty in the South is considered by the UN to be some of the worst anywhere in the world. And as Forbes magazine reported in August, the real economy isn't booming.

For now The Conners remain on the air, with their lives and their dignity intact, if only just barely. I hope that ABC and its viewers will keep the show on the air long enough for us to keep talking about class and culture—and about class struggle. The struggle is real.

Kathy M. Newman

-- via my feedly newsfeed

West Virginia GDP -- a Streamlit Version

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.

-

John Case has sent you a link to a blog: Blog: Eastern Panhandle Independent Community (EPIC) Radio Post: Are You Crazy? Reall...

-

---- Mylan's EpiPen profit was 60% higher than what the CEO told Congress // L.A. Times - Business Lawmakers were skeptical last...

-

via Bloomberg -- excerpted from "Balance of Power" email from David Westin. Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the late...