Why Democracy Fails to Reduce Inequality: Blame the Brahmin Left

A new paper by Thomas Piketty finds that major parties on both sides of the political spectrum have been captured by elites and warns of a future political system that pits "globalists" against "nativists."

Economists and political scientists often point to rising inequality as one of the main drivers of the current wave of populist politics engulfing Europe and the US. Income and wealth inequality have been at the forefront of the political debate across Western democracies for a long time, fueling voter dissatisfaction and leading to the widespread perception that the system is "rigged." And yet Western democracies are no closer to addressing this crisis than they were two years ago, with a recent report by Britain's House of Commons finding that the world's richest one percent is on track to hold as much as two-thirds of global wealth by 2030.

In theory, at least, this kind of growth in inequality is expected to bring about public demand for redistributive policies, such as higher taxes on the rich. So far, though, this has not been the case at all. Instead, we're seeing far-right populist parties gaining momentum at the expense of moderates and center-left parties, spurred by outraged white working- and middle-class voters rebelling against the perceived interests of "globalist" elites.

Why has democracy failed to slow down rising inequality? And why is the current populist wave characterized by so much nativism and xenophobia when—as David McKnight recently noted in The Guardian—a progressive version of populism also exists?

In Project Syndicate and in a recent interview with ProMarket, Harvard economist Dani Rodrik provided one possible explanation: the left, he argued, has been largely complicit in the policies that led to rising inequality—namely globalization and financial deregulation—and has therefore been "missing in action" for the past 20 years.

In his 2016 book "Listen, Liberal," social critic Thomas Frank mounted a similar critique: the Democratic Party, which traditionally represented the working and lower middle classes, has gradually abandoned its traditional base and class commitments over the last 40 years, he argued, in favor of a technocratic elite of well-educated and affluent professionals. This entailed a set of policies that served to deepen American inequality, rationalized under the now-fetishized idea of "meritocracy," under which many leading Democrats came to believe that (to quote Larry Summers) if inequality has gone up, it is because "people are being treated closer to the way that they're supposed to be treated." By failing to tackle the growth of inequality, argued Frank, the Democratic Party has ceded its historic role as "party of the people," thus leaving far-right populists to fill the vacuum it left.

In a new paper, French economist Thomas Piketty, who became a worldwide sensation with his seminal 2013 book on inequality "Capital in the Twenty-First Century," attempts to answer both questions: why democracy failed to address the rise of inequality, and why the response so far has been a turn to nativism.

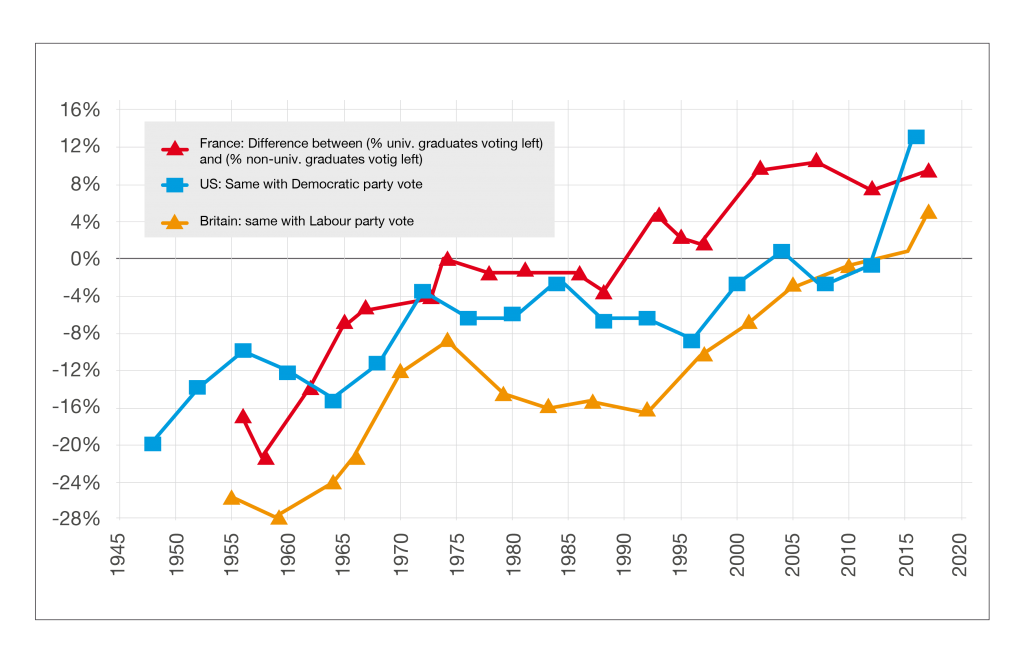

To do so, Piketty tracks electoral trends across three countries—the US, Britain, and France—from 1948 to 2017. Despite their vastly different electoral systems and political histories, he finds, a similar trend can be found in all three countries: left and center-left parties no longer represent the working- and lower-middle-class voters they were traditionally associated with.

Instead, both the left- and right-wing parties have come to represent two distinct elites whose interests diverge from the rest of the electorate: the intellectual elite ("Brahmin Left") and the business elite ("Merchant Right"). Piketty calls this a "multiple-elite party system": the highly educated elite votes one way, and the high-income, high-wealth elite votes another.

With the major parties on both sides of the political spectrum becoming captured by elites, it's no wonder so many voters feel unrepresented. A 2016 poll by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) found that more than six in ten Americans don't feel that their views are being represented by either of the major political parties. A separate poll by Quinnipiac University found that 76 percent of Americans agree with the statement "Public officials don't care much what people like me think."

In this respect, the rise of anti-establishment populism can be seen not as an anomaly, but as harbinger of what could very well become "the central political cleavage of our time."

The More Educated Voters Are, the More They Vote for the "Left"

In order to track the evolution of party systems and political cleavages, Piketty uses post-election surveys held in each of the three countries. While this approach has many benefits, he notes, it also has some drawbacks, namely a limited sample size and the fact that such surveys were not conducted before the 1940s. The difference in the three countries' electoral systems also present some challenges: in Britain, Piketty examines legislative elections; in the United States he only looks at presidential elections; and in France he examines both presidential and legislative elections. In France, he simplifies the country's multiple-party system into broad "left" and "right" categories, and in Britain he excludes third-party votes and focuses on Labour versus Conservatives.

When examined in these terms, he finds, voters in all three countries have historically been split almost evenly between right and left.

Despite the immense differences in the three countries' political histories and socioeconomic structures, Piketty finds some striking similarities in the evolution of their party systems. In all three countries, in the 1950s and 1960s, the political system used to be divided along class lines: a vote for left-wing parties in France and Britain, and for the Democratic Party in the United States, was typically associated with low-income, low-education voters. The more educated, wealthier voters tended to vote for the right.

Starting with the 1970s, however, the three countries underwent a similar process of political realignment: the traditionally left parties, which used to be associated with poorer, less educated voters, have gradually become associated with the highly educated "intellectual" elite—as opposed to the high-wealth, high-income elite that still largely votes for the right.

The more educated voters are, he finds, the more they vote for "left" parties: in 2016, for instance, 70 percent of American voters with master's degrees (which account for 11 percent of the electorate) voted for Hillary Clinton, along with 76 percent of voters with PhDs (2 percent of the electorate). Among voters with bachelor's degrees (19 percent of the electorate), 51 percent voted for Clinton. Among those with only a high-school education (which account for 59 percent of voters), however, only 44 percent voted for the Democratic candidate.

Even in Britain, the most "class-based" system of the three, where it was once very rare for educated voters to vote for Labour, the evolution ended up looking very similar: university graduates have massively shifted to Labour over the last few decades, particularly those with advanced degrees.

While globalization and immigration have played a big role in the creation of this "multiple-elite" party system, notes Piketty, the process that led to its creation began before these issues became so politically charged, and possibly would have taken place without them. The crucial factor was the growing number of voters with higher education levels, which, he writes, "creates new forms of inequality cleavages and political conflict that did not exist at the time of primary and secondary education."

Some have criticized Piketty's study for not giving enough weight to immigration and racism, particularly when it comes to the realignment of Democrats and Republicans in the United States around racial issues. Piketty does acknowledge that the strong support of Muslims in France for left-wing parties and of African-Americans and Latinos for Democrats in the United States cannot be explained solely by variables such as income, education, and wealth, but has to take into account the substantial hostility minorities encounter from the right side of the political spectrum. He also acknowledges that racial sentiments did play a part in driving certain white low-income, low-education voters away from Democratic Party. Nevertheless, he argues, the trend holds: America has become a multiple-elite party system, even when entirely excluding the Southern states.

Overall, the polarized debate over immigration has a curious effect on multiple-elite party systems: it ruptures them even more. In France, Piketty finds, the share of voters that oppose immigration has actually declined, from 70 to 75 percent in the 1980s to about 50 percent today. The intensity of the right/left cleavage, however, has increased as the issue became much more divisive over time.

While evenly split on immigration, French voters are also roughly evenly split on economics, with 52 percent of French voters supporting redistributive measures to reduce inequality. However, these halves are almost entirely uncorrelated, resulting in a "two-dimensional, four-quarter political cleavage" between four groups: the "internationalists egalitarians" (which Piketty describes as "pro-immigrants, pro-poor"), the "internationalists inegalitarians" (pro-immigrants, pro-rich), the "nativists-egalitarians" (anti-immigrants, pro-poor), and the "nativists-inegalitarians" (anti-immigrants, pro-rich).

Globalists vs. Nativists

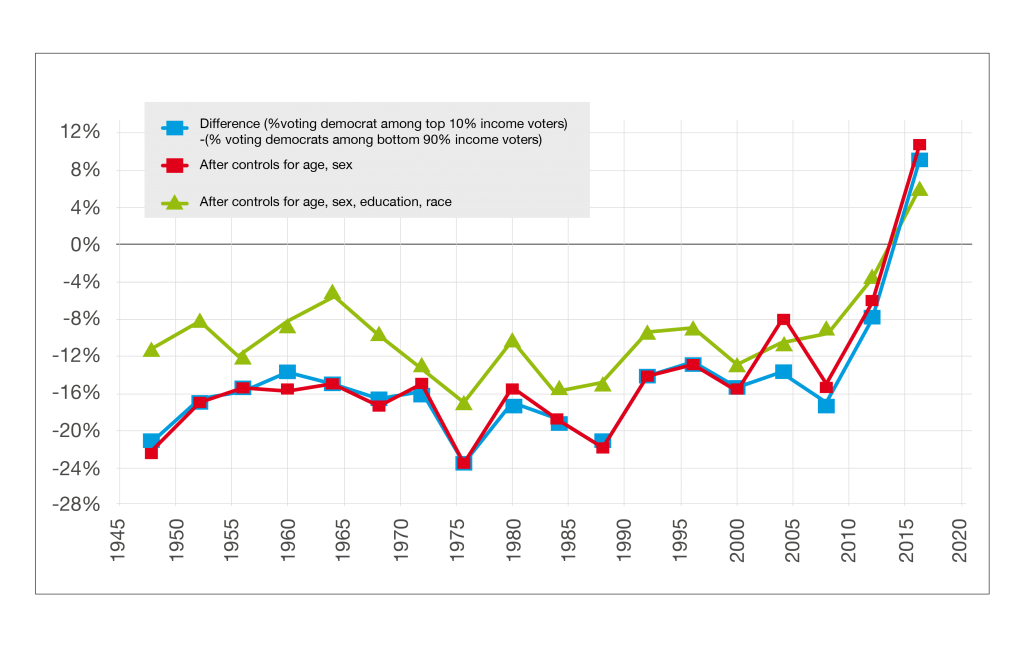

The 2016 US presidential election, notes Piketty, represented yet another potential political realignment: for the first time, the top 10 percent of voters (based on income) voted Democrat. A similar phenomenon was seen in France's 2017 presidential elections (Emmanuel Macron's voters were "highly affluent," Piketty notes), suggesting that high-income, high-wealth voters were also moving in the direction of the "left."

This, writes Piketty, could be an anomaly, owing to the unusual nature of the 2016/17 election cycles in France and the United States. But they could also herald something much more significant: a complete realignment of the party system, which would move further away from traditional notions of "left" and "right," instead pitting "globalists" (high-income, high-education) against "nativists" (low-income, low-education).

Yet this transformation is far from certain. The "multiple-elite" structure could also stabilize—the 2017 British election, notes Piketty, points in that direction. While in France and America there are signs that high-income voters are shifting to the "left," in Britain there is no sign of this happening anytime soon. In fact, he writes, the last two British elections (in 2015 and 2017) have "reinforced" the multiple-elite nature of the British party system: high-education voters have increased their support for Labour, while high-income voters increased their support for Conservatives.

None of the above two options seems likely to lead to a reduction in inequality, renew voters' trust that democracy can address their problems, or overcome nativist sentiments. However, Piketty proposes a third possible trajectory, one in which left-wing parties (or nativist parties, though this is less than likely) return to their long-abandoned class-based politics and adopt a powerful progressive agenda focused on reducing inequality through redistribution. Without such an agenda, he argues, politicians would find it difficult to unite low-income, low-education voters and build a wide enough coalition able to counter inequality.

But first, left parties would necessarily have to put an end to Brahminism and convince voters they represent more than the sum of their elite.

For further discussion about Piketty, listen to Kate Waldock and Luigi Zingales discuss "Capitalism in the 21st Century" in an episode of the Capitalisn't podcast:

Harpers Ferry, WV