Our current political moment

Our current political moment

Before I begin today's note, a comment on recent political events. We have just seen the Senate pass a bill that will systematically undermine previous efforts towards progressive taxation, widen income gaps, deepen challenges to social mobility, and start a process of inexorably chipping away at the Affordable Care Act, exposing millions to again being uninsured or having substandard insurance. At the same time, Congress continues to fail to reauthorize spending for the Children's Health Insurance Program, which provides low-cost health insurance coverage for families who do not qualify for Medicaid. These are all, sadly, systematic efforts to place the interests of a few—in particular, those who already have substantial advantage in this country—over the interests of the many. Early in the Trump administration, I wrote about its potential impact on the health of the public. It is deeply troubling that the worries that were then just hints on the horizon are slowly coming to fruition. To my mind, the challenges of the present are, once again, a reminder of the profound impact that politics can have on population health, and why our work must be concerned with ensuring that the values that animate public health are front and center in the national conversation. While there is little to lift the spirit in the face of some of the administration's recent actions, I continue to hope that these years will prove formative for a generation of students who are coming of age during a time of trial for the health of populations, and who will use the troubled present as inspiration for work that improves the conditions that create health in the coming decades.

To continue our engagement with this topic, on Tuesday, May 8, 2018, we will, together with the Lancet Commission on Public Policy and Health in the Trump Era, host a daylong symposium, called "The Trump Administration and the Health of the Public." The symposium will aim to catalyze data-informed discussion about how the changes we are seeing to national policy may influence public health now and in the future. Additional details will be posted online. For today—a note that explores the forces that underlie our country's political shifts, written with the goal of implementing healthier polices on the national stage, once our present moment has passed.

On game theory

Those of us who study the health of populations know that populations do not always act in their collective best interest. Americans, for example, have long been ambivalent about policies that could improve the country's health, such as federal welfare benefits and universal health care. Additionally, as Professor Jacob Bor's research shows, many of the country's unhealthiest citizens voted for Donald Trump, who has since done much to undermine the polices and programs that safeguard health in the US. What makes people act against their core interests? Journalist Thomas Frank famously tackled this question in his book, What's the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Won the Heart of America. The book looks at how Kansans went from being historically progressive to strongly conservative, electing candidates who, once in office, implemented economic policies that disadvantaged the very working-class voters who put them in power. With this in mind, today's note seeks to answer a perennial, perplexing question: Why do populations oppose measures that could improve their health?

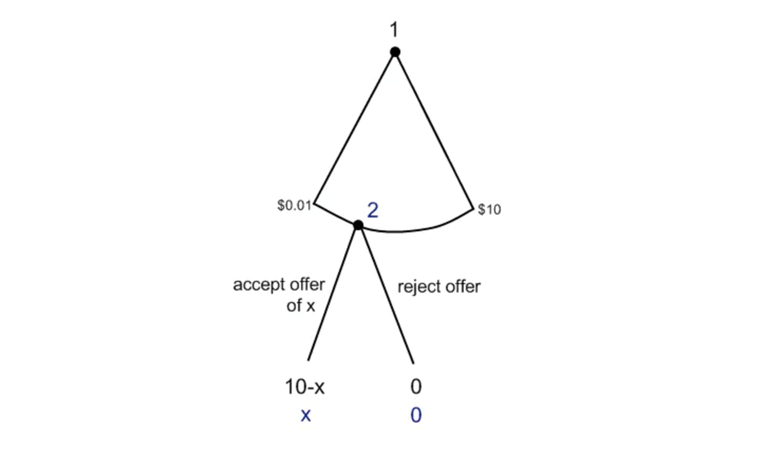

To answer this, I will draw an example from a perhaps unexpected place: the world of game theory. It is here that we encounter the ultimatum game. The ultimatum game is an economic experiment in which two players participate. Player One is given a sum of money and the choice of how to apportion it between herself and Player Two. She may give Player Two all of the money, or none. The second player then chooses whether to accept or reject the first player's offer. If he rejects it, both players get nothing. The game depends on individual self-interest regulating itself, so that each player will benefit, however unequally. Figure 1 provides a useful visualization of the game's dynamics, when the total sum is $10.

Theoretically, assuming rational actions on the part of both participants, the second player would always accept whatever Player One offers, since something is always better than nothing. Yet this is not invariably the case. On average, second players tend to accept offers above 40 percent of the total sum, with about half of all second players declining offers below 30 percent. The motivation of players who decline the lower offer is not difficult to guess. If they believe that Player One is taking advantage, or benefitting unfairly from the rules of the system, it opens the door to a sense of competition, turning what should be a mutually beneficial exchange into a zero-sum game. As a consequence, the second player would rather no one benefit, than someone do so apparently at his expense.

Lessons for our work in population health

Our politics often shows how this motivation can be used to rally support for policies that do not always serve the people who vote for them, but that nevertheless speak to the anger and anxiety of these populations—to their frustration with the status quo or suspicion of certain socioeconomic groups. This can mean the creation of scapegoats, who come to embody "the unfair first player"—the individuals or groups who seem to undeservedly benefit from the advantages of a given policy. During the 2016 election, for example, then-candidate Donald Trump leveraged fear of "the job-taking immigrant" into working-class support for a movement that has, so far, done little to benefit the working class. More recently, opponents of the Affordable Care Act have argued, in effect, that healthy people should not have to subsidize the care of sick people, that those "who have done things the right way" should be rewarded, and that those who have "not" should fend for themselves.

How can we avoid this "ultimatum game trap?" Game theory suggests a possible solution. Suppose each player in the game is weighing her or his options. Player One knows that she must offer Player Two something, or else Player Two has no incentive to accept. Player Two knows he can only gain by accepting whatever he is offered, as long as it is more than nothing. Each understands how adhering to this strategy benefits the other player, not to mention their own self-interest. They therefore decide not to deviate from the course of action that will lead to the best outcome for them both: Player One offers a sum, and Player Two accepts it. This solution is called the Nash Equilibrium, named after the economist John Nash. To function, it requires each player to see which course of action is most beneficial for himself and his fellow player, and then to not deviate from what is understood to be the best strategy for success. A "real-world" parallel would be obeying a law that no one has the incentive to break, even if that law were to go unenforced—obeying traffic lights, for example, when a car is driving in your direction. Or, indeed, investing in health as a public good in a country where deleterious social, economic, and environmental influences put populations at risk of injury and disease every day. Through this framework, positive outcomes occur when self-interest meets an awareness of how the needs of others need not conflict with, indeed may even complement, one's own. For populations to make choices that are more in line with their interests, they must first see how what is good for others can be good for them, and vice-versa—that the world does not have to be divided into "winners" and "losers," where someone can only thrive at another's expense.

I have written previously about the challenge of implementing measures that could improve the health of all, when some individuals or groups perceive these measures to be burdensome. I suggested that vaccines are an example of how something that was once viewed with skepticism can eventually achieve acceptance when its proven benefits become widely known. It is encouraging that this is so—that spreading awareness of a public health good can be enough to change minds and persuade populations to accept initiatives for the betterment of all. However, as we have seen, this is not always possible. Sometimes, a measure's benefits can be clear, yet it will still be opposed on the grounds that it might help the wrong people for the wrong reasons. Often, this opposition has its roots in the resentment of particular socioeconomic groups. To overcome this resentment, and apply the Nash equilibrium to population health, we must not only promote health as a collective value, we must continue to emphasize that this value is not attainable as long as our society tolerates stigma and hate. These forces have great power to mobilize and mislead, distracting populations from core health interests. For this reason, any effort to nudge the public towards a deeper understanding of the true causes of health must approach advocating for the marginalized not as an incidental goal, but as a central organizing principle. This fits with the mission of public health, and with our school's stated aim "to improve the health of local, national, and international populations, particularly the disadvantaged, underserved, and vulnerable." Our pursuit of these goals points us towards a truly broad-based movement in favor of the institutions and policies that promote health. Ultimately, it is through cooperation, rather than competition, that we can best apply the lessons of game theory to the work of public health, empowering populations to know, and do, what is in their best interests.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm Regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo for his contributions to this Dean's Note.

Previous Dean's Notes are archived at: http://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Our current political moment

Our current political moment