Wednesday, December 14, 2016

Donald Trump Is Not a Legitimate President Elect and He Never Will Be

I know--I was a U N election observer in Sierra Leone in 1996.

Trump us disqualified because of intimidation and police activity. In fact, the FBI played a threatening role with the HRC campaign and with voters. Comey went way out of bounds voicing his own opinions when announced the emails investigation.

Foreign interference. 17 U S intelligence agencies have confirmed that Russia hacked U S political organizations to sway and influence the election. Now, even top Republicans have announced Congress will investigate.

Widespread vote theft and voter suppression. 87 voting machines were inoperable in Detroit on Election Day. 87,000 votes were destroyed. 300,000 voters were removed from the rolls in Wisconsin. Donald Trump and the Republican Party mounted an unprecedented fascist or totalitarian-like effort to snatch victory away from democracy. It is on such a comprehensive foundation that we must build our RESISTANCE. It is critical that our resistance to Trump's losing election is based on the broadest foundation to attract the largest constituency to our righteous fight.

Sent from my iPhone

Paul Ryan: Trickle Downer of the Week [feedly]

http://prospect.org/article/paul-ryan-trickle-downer-week

As Congress prepares to end its lame-duck session, Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan races to grease the tracks for his trickle-down tax plan.

His partner in this latest GOP shell game is Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who told reporters at a Capitol Hill press conference Monday that after Republicans finish gutting Obamacare (their first target), they intend to use a second, filibuster-proof, budget reconciliation process to ram through comprehensive tax reform.

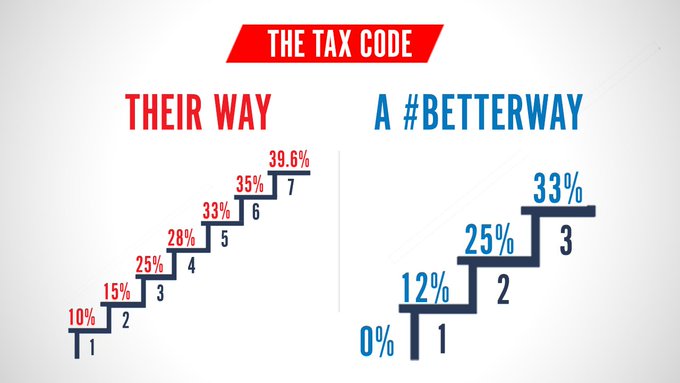

The speaker would have you believe that his reform plan merely simplifies the tax code by shaving the number of tax brackets from the current seven—"their [the Democrats'] way"—down to just three—a #BetterWay—the average taxpayer will save big bucks.

He recently tweeted:

The U.S. tax code is too complicated. ← Retweet if you agree. #BetterWay

But Ryan, who's conned Washington into thinking he's a veritable policy wonk, uses the rhetorical cover of a "leaner, meaner" tax code to hawk neo-Reaganomics. Fewer tax brackets do not make for a fairer or less complicated system: Flattening the tax code by reducing the number of brackets is a regressive tax strategy. Many on the left argue that adding more brackets would acutally produce a better system of taxation.

Ryan's plan is pure trickle-down economics: It would dramatically reduce the top marginal-income and corporate tax rates and eliminate the estate tax entirely.

For the average taxpayer, Paul Ryan's tax framework is no better than Donald Trump's. If anything is unique about Ryan's tax plan, it is that he managed to make it even more regressive than past GOP plans. According to an analysis by the Tax Policy Center, the top 1percent of taxpayers will have received the overwhelming share, about 99.6 percent, of Ryan's tax cuts—which would be fully phased in by 2025.

On average, the wealthiest Americans would see an 11 percent increase in their after-tax incomes. Meanwhile, the middle fifth of households would receive just $60.

Ryan's "Better Way" plan would reduce federal revenues by $3.1 trillion over the first decade and increase the national debt by as much as $3 trillion. A Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis found that the tax cuts would produce a massive increase in the federal deficit that would not be offset by budget cuts or economic growth.

When 60 Minutes asked Ryan whether the rich would benefit most from his tax plan, he said: "Here's the point of our tax plan. Grow jobs. Get this economy growing. Raise wages. Simplify the tax system, so it's easy to comply with." However, tax cuts aimed at the rich do not "grow jobs." Nor do they increase incomes for the working and middle classes.

Do not be distracted by Trump's antics. Instead, watch out for the speaker's "simplification" ruse. It's a Trojan horse for trickle-down economics 2.0 dreamed up by Paul Ryan, our Trickle Downer of the Week.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

How Fast Could GOP Congress Get Obamacare Repeal To Trump's Desk? [feedly]

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/12/14/505439759/how-fast-could-gop-congress-get-obamacare-repeal-to-trump-s-desk

GOP leaders hope to deliver a bill by Inauguration Day that repeals the Affordable Care Act. But budget veterans say even the quickest attempt would take a week or two longer, and maybe months.

(Image credit: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Everyday Encounters: Antagonism in the Sharing Economy [feedly]

https://workingclassstudies.wordpress.com/2016/12/12/everyday-encounters-antagonism-in-the-sharing-economy/

Much has been written about the growth of the sharing economy where information technology, such as mobile apps and automated software facilitate interactions between businesses, individual workers, and customers. Proponents argue that the system provides greater access to goods and services at lower prices while reducing costs for employers and independent contractors. They also claim that, in the gig sector of the sharing economy, workers gain flexibility because they determine their own hours, tools, and working conditions while raising potential earnings.

Regardless of whether we buy these claims about benefits to workers, there are numerous signs that the sharing economy creates antagonism between workers and customers. The apps and automated systems that underlie these new work structures require both workers and customers to rely on technology, yet the systems are often faulty and poorly designed. While these systems promise transparency and trust, they also create tensions. For example, such systems unfailingly include algorithmic performance assessment of service industry workers. As technology writer and software engineer Tom Slee has argued, "Rather than bringing a new openness and personal trust to our interactions, [such shifts are] bringing a new form of surveillance where service workers must live in fear of being snitched on, and while the company CEOs talk benevolently of their communities of users, the reality has a harder edge of centralised control." The increasing antagonism resulting from the perpetuation of inequality among "stakeholders" has received insufficient attention.

Service industry workers have long operated as the front-line interface with customers, having to respond to complaints about company practices that they don't control. Now service workers have even less control due to structural and technological platforms. When platforms fail, inconveniencing and frustrating customers, workers have little power to resolve disputes. At the same time given the dependence on technology and lacking access to customer information, they cannot build relationships with customers over time. Indeed, it is almost impossible to contact the same customer service representative twice, so consumers then become obliged to give the same information over and over again. The interactions between customers and workers often predictably devolve, generating frustration, impotence, and anger on both sides and voiceless workers subjected to performance review by customers following interactions. Dependence on technology estranges service workers from customers, undermining the possibility of finding satisfaction on the job because of increased misunderstandings and conflicts.

Just as proponents ignore the way automation undermines the quality of work, they also misrepresent what the sharing economy offers to consumers. Although they claim that automation generates a high degree of efficiency and autonomy to customers, they overlook time-consuming administrative inefficiency and poor customer service. For example, in the gig sector, where a few companies dominate particular markets, companies have little reason to worry about consumer rights. No doubt this contributes to the increasing conflicts and complaints associated with technology and social media in air travel, banking and other financial institutions, cable television and communications companies, insurance and health firms, and universities.

To make matter worse, customers in the sharing economy must go to great lengths to seek basic information and answers to queries. Even when customers succeed in reaching customer service representatives, they are often treated with robotic indifference or a stilted hyper-courtesy that barely conceals institutional disdain. Customer service representatives often speak in a language of faux-camaraderie that couches authoritarian directives as suggestions as in the ubiquitous "Why don't you go ahead and. . ." Corporations exacerbate the problem by pairing this passive-aggressive treatment with service fees and other administrative charges, so that customers are not only treated poorly, they pay for that privilege. This problem affects less educated and less well-off customers, especially, who may have less access to or experience with technology and the Internet and are less able to afford fees or phone charges.

Some companies will not make themselves available at all, having developed bureaucratic systems that cultivate inaccessibility. For example, Amazon has refused to engage with customers directly by phone. Other companies have trained call center employees to repeat marketing mantras and to speak like machines giving pre-scripted answers that may or may not match a customer query. These bureaucratic obstructions, including automated customer service and phone banks and the outsourcing of customer service "chat" and email services, only deepen the antagonism of customers toward corporations and their intermediaries.

The antagonism generated by these practices affects working- and middle-class people far more than it does the elite, who often enjoy preferential treatment through concierge services in hospitals or all business-class airports. Such VIP/concierge services help elites navigate organizations, technology, and services, while most customers must work harder to gain access to restaurants, hotels, sports and other entertainment events, and a range of other services and sites. As Cathy O'Neil in Weapons of Math Destruction has noted, "The privileged, we'll see time and again, are processed more by people, the masses by machines."

Non-elites unable to "opt-out" of the antagonistic service economy may find consolation in the techno-future conjured up by Amazon Go, which showcases the pleasures of never having to interact with other humans at all. In glossy ads for what Amazon deems the "world's most advanced shopping technology," checkout is eliminated – as are retail clerks — as shoppers employ an app that simply charges them for the items they select. Privileged relationships with commodities dominate the scene in an ad in which hardly anyone speaks to or even looks at anyone else.

In the past few months, commentators have explained support for Donald Trump in the US or "Brexit" in the UK as expressions of populist rage. One source of that rage may well be everyday encounters of the kinds sketched here. If working-class people feel like they don't matter in contemporary capitalism, that may reflect the challenges of working in the sharing economy, with its low wages, limited autonomy, and inherent conflicts, but also the challenges of an antagonistic service culture that mounts daily micro-assaults on people's dignity and rights.

Diane Negra, University College Dublin

John Russo, Kalamanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor, Georgetown University

Diane Negra is Professor of Film Studies and Screen Culture and Head of Film Studies at University College Dublin.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Stumbling and Mumbling (Chris Dillow)The productivity silence [feedly]

http://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2016/12/the-productivity-silence.html

Simon recently tweeted that it is important to ask why we are not talking about the crisis of stagnant productivity all the time. He's surely right: this is our most important economic problem. So why isn't it a top political priority? The fault, I suspect lies with voters, politicians and the media.

In voters' case, it's because stagnant productivity isn't very salient. "Some Latvians moved in down the road and now my son can't get a decent job" is an obvious story to tell – even if it's wrong. But the UK's productivity slowdown, and our low productivity relative to other developed countries, is a story about countless things that UK businesses do less well than their French or American counterparts and about impersonal forces such as low investment and innovation, slower world trade growth, a fear of credit constraints, a slowdown in entry and exit and so on. Such things are important, but not vivid.

Reinforcing this is a self-serving bias. People would rather blame their low pay upon immigrants than on the fact that they are incompetent unskilled buffoons.

Herein, though, lies a defect of modern democracy. Because the notion of consumer sovereignty has taken over politics, politicians think that what they're "hearing on the doorstep" matters. In some ways it does. But it can also be a lousy guide to what really matters economically. Few politicians are brave enough to tell voters: "you shouldn't worry about that; this is a bigger problem."

And, of course, the media reinforces this. The BBC takes its agenda from politicians and the press. If these are talking about what are trivial matters economically speaking such as immigration or government borrowing, the BBC will reflect this and so ignore productivity. This is reinforced by three other factors:

- The BBC prefers controversy. A row between idiots – one of whom is usually called Nigel – is better TV or radio than an expert discussion of productivity.

- Official productivity data comes out only quarterly (though it can be inferred from monthly data), whereas figures on inflation and government borrowing are monthly. This means the news will more often report the latter than the former.

- Productivity is a dry abstract story. The media are much better at human interest stories than in analysing social structures and impersonal forces.

But perhaps there's something else. Many people do think: "I'd be better paid if this place weren't so badly managed". This sentiment, however, never gets onto the political agenda and the connection from this notion to worker democracy never gets made. Bosses are regarded as the only experts whose competence is unchallengeable. Maybe therefore the relative silence about productivity is yet another example of how managerialism – or neoliberalism if you insist – has triumphed so totally.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Bernstein: In advance of the Fed’s announcement on rates tomorrow… [feedly]

http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/in-advance-of-the-feds-announcement-on-rates-tomorrow/

The Fed started its December meeting today, one in which they are highly likely to decide it's time for another rate hike. Prediction markets are posting a 95 percent probability that the Fed lifts their benchmark interest rate tomorrow from a target range of 0.25-0.50 basis points (hundredths of a percent) to 0.50-0.75. I'm confident that prediction is correct.

So, whassup with that?

Why now?

Why is the Fed likely to raise in this versus prior meetings? What's changed? A lot, actually.

While the Fed is thankfully somewhat insulated from politics, they have to stay on top of interactions between politics, fiscal policy, markets, and growth. The so-called Trump rally—the DJIA is up almost 9 percent since Nov 8—is built on the notion that a business-friendly president whose cabinet is "stocked" with bankers and billionaires will oversee more upward redistribution of growth, along with financial market deregulation.

[The fact that such policies have, in the past, exacerbated inequality and inflated bubbles is clearly not…um…the focus of markets right now. Sometimes I think the fatal flaw of humans reduces to our unwillingness to give a crap about the future (inequality, recession, melting icecaps) when we can have something today. But I digress…]

Operationally, the Trump rally reflects his plan for a big, regressive tax cut (also infrastructure investment, though see below). Inflation and interest rates have firmed significantly since his election, based on the expectation that he'll inject a serious slug of stimulus into an economy which is already nudging towards full employment.

Also, as the jobless rate has fallen, wage growth has accelerated, from around 2 to 2.5 percent, on average. The price of a barrel of oil is also up 15 percent (almost $8) over the past month.

All of this has bumped up inflationary expectations, if not core (sans oil, food) inflation itself. The figure below shows two series of market-derived inflation expectations, both of which turn up pretty sharply towards the end (before the election, but the daily measures show a spike afterwards). There's the "5-year, 5-year forward inflation expectation rate," which captures expected inflation over a five-year period that begins five years from now. It's just above 2 percent (the Fed's target rate), meaning investors expect inflation to average a little over 2 percent between December of 2021 and December of 2026. The 10-year TIPS breakeven rate reflects similar expectations. (This rate is the difference between the yield on bonds that include an inflation risk premium and those on inflation protected bonds; once you "net out" the latter, what's left over is inflation expectations.)

The thing is, no one knows what president-elect Trump and the Congress will actually pull off. My guess is that these expectations are directionally correct but overblown. There will be a big tax cut, but perhaps not as big as the markets are pricing in. A serious infrastructure dive may also be a bigger question mark than many investors seem to think (Trump's original idea is limited and not well constructed [sic]).

But it doesn't matter what I think. What matters is what the Fed makes of these expectations. More precisely, it's the extent to which such movements signal to a majority on the FOMC (the group that votes on the rate hike) that anchoring inflationary expectations requires a hike. Based on that standard, I can certainly see where they'd react to the recent upturns with tomorrow's predicted increase

But is a rate hike warranted?

What hasn't changed much is the actual, underlying rate of core, PCE inflation, the Fed's preferred benchmark. As you see in the next figure, excepting a few months in early 2012, it's undershot the Fed's 2 percent target for eight years! Moreover, it's generally agreed that the target is an average, not a ceiling, so having been below it for so long, there's room to run above it for a while.

In fact, it's essential that we do so. Even grizzled full employment warriors like myself agree we're getting close to that long-awaited condition, though underemployment rates and prime-age employment rates are still too high/low, points on which Chair Yellen has been consistently clear. Moreover, the low jobless rate is finally delivering some long-missing bargaining clout to middle- and lower-wage workers, and the last thing those workers need is to fight against the headwinds of higher interest rates.

But isn't their wage growth bleeding into price growth? Not at all. My colleague Ben Spielberg made the following scatterplots. The first one shows yr/yr inflation (PCE core again) against nominal wage growth for blue collar workers in factories and non-managers in services, about 80 percent of the workforce over the full length of the series, which starts back in the mid-1960s.

While wage and price growth correlate over the life of the full series, over the current expansion (gray dots) the correlation goes the wrong way. But, you say, this has been a uniquely weak expansion with wage growth for these workers coming late in the game. OK, I say back, let's look at the strong 1990s recovery (salmon dots; i.e., Ben tells me they're "salmon"; I'm color blind and even if I weren't, I wouldn't use salmon dots), where full employment eventually drove solid real wage gains across the pay scale. Same thing—the correlation again goes the wrong way.

I should mention, non-incidentally, that we got to full employment in the 1990s because Alan Greenspan ignored those telling him that the unemployment rate was falling too far below what was erroneously believed to be the "natural rate" of 6 percent.

OK, perhaps I've convinced you on the wage-growth-not-driving-inflation part of the story (there's academic evidence for this too). But just because you don't see wage pass-through to prices doesn't mean that full-resource utilization, as proxied by low unemployment, won't drive up inflation. Then why hasn't the inflation line accelerated in the PCE figure above? Yes, the scatterplot below shows low inflation at high unemployment, but it also shows low inflation at low unemployment.

Look, the Fed's almost sure to raise tomorrow, and frankly, at this point, I think the volatility induced by surprising markets would be an own-goal kick that the Fed should probably avoid. But I don't trust these recent blip-ups in markets and expectations based on the notion that Trump and his merry band of billionaires are going to be great for investors. And even if they are, a) the Fed may push back the other way by raising rates more quickly, and b) unless unemployment stays very low, none of these goodies are trickling down to workers.

I don't mean to slight the incoming econ team; they deserve a chance and they're certainly inheriting a different economy than the one faced by the team I was on 8 years ago.

But my priors suggest that the Fed may be the only rational, fact-based economists at the controls for a while…maybe a good, long while. They need to block out the noise, remain in data-driven mode, and allow the recovery to continue reaching those who've only recently begun to benefit from it.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Bernstein: Important new work on inequality and immobility [feedly]

http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/important-new-work-on-inequality-and-immobility/

I wrote about some of the findings from this new paper for a WaPo post this AM, but there's a ton more to be said about it, as the authors have created a very rich data set on US income.

My point this AM was that these data–and more about the data in a moment–strongly support the case that, while I'm all for faster growth, that alone will not reverse the post-1980 trend in inequality.

The second figure in my piece provides a very simple, rough decomposition of the impact of slower growth and inequality on the average income of the bottom half of adults, showing that about two-thirds of the stagnation is attributable to the growth of inequality.

One complaint about that finding, as I note in the piece, is that the income slowdown could be demographically driven, as the increased shared of retirees over this period is putting downward pressure on income growth.

The figure below, from Piketty et al's paper, challenges that suspicion by breaking out the income trends of various age groups. In fact, the only group whose income is up over the period is the >65 folks. Of course, their incomes are below average over most of the period, so there could still be a composition effect here, but there's no questioning, at least based on these data, that working-age adults faced seriously stagnating incomes over this period.

Regarding the data, the compilation of this information, which distributes aggregate, national income to individual adults, is a Promethean task for which I give the authors tremendous credit. There's no way to complete this exercise without many, many assumptions, and as is always the case in economics, every assumption can be questioned.

They have to make assumptions about the incidence of taxation–whose income gets dinged–about government spending–who benefits from spending on infrastructure or defense–about how income is shared in families, and many other gnarly questions.

So far, I've seen little to which I'd object, and to their credit, far more than almost anyone in our business, they provide a) the underlying data, so you can see for yourself how some assumptions play out, and b) various tabulations based on alternative assumptions.

My one question thus far is how they treat budget deficits (my bold):

"Government revenue usually does not add up to total government expenditure. To match national income, we impute the primary government deficit to individuals. We allocate 50% of the deficit proportionally to taxes paid, and 50% proportionally to benefits received. This effectively assumes that any government deficit will translate into increased taxes and reduced government spending 50/50. The imputation of the deficit does not affect the distribution of income much, as taxes and government spending are both progressive, so that increasing taxes and reducing government spending by the same amount has little net distributional effect. However, imputing the deficit affects real growth, especially when the deficit is large. In 2009-2011, the government deficit was around 10% of national income, about 7 points higher than usual. The growth of post-tax incomes would have been much stronger in the aftermath of the Great Recession had we not allocated the deficit back to individuals."

I don't have a better way to do it, but this seems off to me. It seems to assume that deficits get fully paid off–through higher taxes and lower spending–in the year they occur. I understand the assumption in the accounting sense of hitting their national income target, but it's a) unrealistic, and b) much more importantly, can have a significant and unrealistic negative impact on incomes in periods of large deficits (and vice versa for surpluses).

My intuition would be to leave it out and punt on hitting national income. To do so wouldn't make a ton of difference outside of periods when the deficit grows a lot, periods when their current method, I'd argue, returns a result that doesn't really show up in adult incomes.

That said, they'd give up a lot conceptually and in terms of simple presentation if they gave up on hitting national income, so there's a trade off. I will noodle on this further as should the authors, whose noodles are far stronger than mine.

Much more to come on this–I'm saying nothing here on the new Chetty et al work as I haven't yet spent as much time with that relative to this Piketty et al paper. I will say this about Chetty et al. Many of us hypothesized that as inequality increased sharply, it would create barriers to upward mobility. The number of kids stuck in neighborhoods without inadequate investments, barriers to quality educational access, and so on, would grow. This, we thought, might slow the rate of mobility as those children aged.

Earlier work by Chetty et al suggested that the rate of relative mobility had not, in fact, slowed over time. This new work suggests that at least by the metric cited in my WaPo piece, it slows considerably. That's a very important and interesting finding which I'll be looking into more carefully in coming days.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

West Virginia GDP -- a Streamlit Version

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.

-

John Case has sent you a link to a blog: Blog: Eastern Panhandle Independent Community (EPIC) Radio Post: Are You Crazy? Reall...

-

---- Mylan's EpiPen profit was 60% higher than what the CEO told Congress // L.A. Times - Business Lawmakers were skeptical last...

-

via Bloomberg -- excerpted from "Balance of Power" email from David Westin. Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the late...