A satisfactory answer to the question "What is Socialism?" is harder to find than might seem the case at first glance. One reason for this is that the movement has always toggled between the burden of Utopia and the urgency of the fight for justice. This has been true since its earliest days, when Karl Marx and Frederick Engels wrenched the "socialist" label from the ancient network of counterculture communities and coops they called "Utopian" and then pinned the adjective "scientific" to their own project.

Other than the phrases "to raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class, to win the battle of democracy" that we find in the Communist Manifesto, we have very little from Marx and his early followers about how the socialist dream would be realized. The new society didn't seem to look that much different to Marx than it had to the traditional Utopians, with the distinction between them consisting of squabbles about the means to achieve the goal. For Marx and Engels, socialism would come when "all production has been concentrated in the hands of a vast association of the whole nation." It would be, they wrote, "an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all."

Let's remember that in college Marx was educated in German Idealist philosophy. He seemed to think the proletariat as "the ruling class" would usher in an order governed by reason in Hegel's sense, and by Kant's categorical imperative. This would all take place in a polity that resembles Friedrich Schiller's "Aesthetic State," where "man encounters man" only "as an object of free play." It's a society in which, to again quote Schiller, "to grant freedom by means of freedom is the fundamental law" (italics in the original). Marx's idea of renovating the division of labor, expressed in The German Ideology [1] as "to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic" is not that radically different from Utopia as it has been imagined since Plato's day. When Marx saw what he took to be a real life manifestation of his ideas, in the Paris Commune of the spring of 1871, his account reminded me of descriptions of New England town meetings or of some militant union or movement meetings where the community itself made consequential decisions regarding the allocation of power and resources.

Socialists generally subscribe to the idea that the good society is one in which everybody is actively and decisively involved in allocating power and resources in the cause of advancing the common good. They want a society where the equivalent recognition of difference allows social distinctions between persons to be valued rather than subject to discrimination and the imposition of pariah status. It's a place where each person is motivated by selflessness in a community where people cultivate a state of creative leisure we can associate with the term "living aesthetically," and where each and all are materially rewarded in a way that advances equality.

All of this would also take place in a culture that prizes personal material modesty over decadent wastefulness. W. E. B. Du Bois, in a 1930 Howard University commencement speech, summed up this latter point. "We cannot all be wealthy," he said. "We should not all be wealthy." In an ideal society, he added, "no person should have an income which he does not personally need; nor wield a power solely for his own whim." Just as Du Bois was speaking, the ideology of wealth had generated a worldwide depression and the collapse of capitalist civilization, and war fever was preparing the greatest outbreak of barbarism the world had ever seen. Against this, Du Bois proposed "a simple healthy life on limited income" as "the only responsible ideal of civilized folk."

Socialism's hopeful and problematic past

For a long time one's attitude toward the Bolshevik version of the good society was a thick red marker that placed you in one or another corner of the socialist movement. Feelings among the Communist-led project's sympathizers ranged, but few believed the societies created by the Bolshevik Revolution-inspired movement were perfect. Many saw the police state aspects of these societies as a temporary thing. Meanwhile, governments inspired by Marx and Lenin had gained widespread respect for even attempting what every banker and industrialist knew in his heart was contrary to human nature.

Many of those socialists would today say, about the legacy of Bolshevism in power, that whatever good the Communist-led governments accomplished (a point that itself still generates heated debate), they ended up botching the thing pretty badly. There are lots of reasons for this, and it's an easy enough game to speculate on what went wrong. One explanation I like is that Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin all thought the criminal ethos and the acts that necessarily follow from it could be controlled and put to utilitarian use by the revolutionary party and state.

In a 1920 polemic against Karl Kautsky, Lenin defended this proposition. Kautsky was the leading Marxist theoretician of his age. He co-wrote the 1891 Erfurt Program of the German Social Democratic Party, which provoked a comment from Engels that I will refer to in a moment. Lenin focused on the idea of the "dictatorship of the proletariat." This was an invention of Marx and Engels, but it had increasingly come to be seen - since at least the Erfurt Program - as inappropriate to the task of "winning the battle of democracy." Lenin, however, used this notion to defend the repressive aspects of the Soviet state. He took what had been a waning concept in socialist circles, reshaped it, and turned it into his own.

"The revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat," he wrote [2] in The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky (1920), is "power won and maintained by the violence of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie." Lenin's focus on violence alarmed many of the old-line socialists who felt he included them in his definition of "the bourgeoisie." But it was the words that follow that really set the stage for subsequent history. The "revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat," Lenin claimed, was not just violence, but "power unrestricted by any laws" (emphasis added). That opened the gates to the road to perdition.

It also had two other consequences. It helped cement the split between old-line socialists and the newer Communist movement. There also emerged a kind of split personality among members of the latter group, who, while defending democracy at home, often found themselves with the difficult job of also defending - in the name of "proletarian internationalism" - a Bolshevik-led government when it committed some lawless act. I've often wondered if anybody told the Bolsheviks how the revolutionaries at Philadelphia in 1783, who decided to compromise with the criminal slave power tyranny in their own midst, almost wrecked the fragile Republic they'd created, leaving a legacy that threatens its stability to this day. The Bolsheviks' compromise with the ethos of criminality was a foundational corruption that gravely wounded the socialist dream.

In addition, Communists in power didn't believe in autonomy for civil society institutions. They also didn't believe in the separation of powers. After a violent confrontation between the workers and the Workers' State in Germany in 1953, Bertolt Brecht commented, in his poem "The Solution," on the workers having acted contrary to the revolutionaries' expectations. "Would it not be easier," he asked, "for the government/To dissolve the people/And elect another?" Even now, a quarter of a century after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the role of workers' uprisings in ending the Bolshevik version of the socialist dream is little remarked on by those of us who were part of the movement that Lenin's followers started.

During the Cold War, something else seems to have happened to "labor-management relations," just as the old, smoky industrial society was transitioning into a sleeker, more automated model. Management styles seemed to have had little to do with the essence of the labor-capital relationship itself, hence the workers' strikes against socialism. We still used the terms "capitalist" and "socialist" to describe groups of countries, and "Communist and Workers' Parties" to describe the ruling parties in the latter group, but the "two systems," as they were called, grew to look remarkably alike, and the similarities between them did not go unnoticed. Some intellectuals talked about "convergence" of the two systems, and Herbert Marcuse, the most astute observer of this phenomenon, used the term "advanced industrial civilization" to describe the whole reality. The most peculiar thing was that "advanced industrial civilization" had produced alienated workers and elite managers everywhere while at the same time becoming remarkably collectivized, with the public authority ("the state") regularly intervening in economic matters as umpire, owner, or super-manager. It made no difference what flag pins the managers in the front office wore in their lapels.

This all called into question the nature of "real, existing" socialism. Was it a "separate" system from capitalism, or just a type of industrial society whose modes of meritocratic social mobility and forms of popular political and economic participation and decision-making looked strange from the point of view of those who favored liberal representative democracy? In the end, these questions were rendered moot by the collapse of the Communist-led governments in Europe, and by the reinstitution of modified forms of private property in the means of production and exchange, accompanied by the muting of revolutionary ideology and rhetoric by China and other Bolshevik-inspired countries. These changes threw socialists of all schools into a state of confusion, but it did not remove the fundamental questions or the basic problems that dogged the movement.

Rethinking "class consciousness"

Socialists today still see ourselves as "change agents" (to borrow a term from academia), who work hard to improve society in the here-and-now, hoping this will help the "vast association" of wage earners figure out how to wield power. However, it's still maddeningly difficult for us to describe the new society and how to get there. For one thing, today's capitalism is not our great grandparents' capitalism. To illustrate the point, take The Jungle, the 1906 novel by Upton Sinclair. This is probably the most important socialist and working class novel ever published in this country. The Jungle depicted what was, in 1906, the normal world, and correcting it was often seen as edging around the border between the impossible and the possible. Yet here's the difference. Today we see those same conditions as a violation of norms. Then there are the aspirations of Jurgis Rudkis, the novel's protagonist. Does he just want "socialism," or does he want a better life? And if he wants the latter, does that mean he wants to remain a "worker"? At the heart of these questions lies the conundrum of socialist identity.

Some one hundred years ago, Lenin tried to sever the questions, "what is socialism," and "what does the worker want," from each other. Focusing on the latter question, he argued, was "economism," For him, the only revolutionary form of class consciousness was "socialist" consciousness. Lenin refused to put the "economism" question first. But what if he had? If we try to reunite these two questions and put the "economism" question first, the answer might surprise us. That's because if the wage earners want to raise themselves to the position of the ruling class, only to spend their days raising cattle, hunting, fishing, and criticizing, maybe it means that the working class wants to become something other than a "working class." Maybe the working class wants to liquidate itself as a class, to liquidate classes as such, and to turn the whole of society into a kind of middle class Utopia.

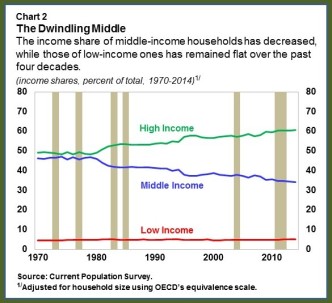

Marx, Lenin, and their followers might have agreed with the first two points, while scoffing at the third one. The "middle class," for them, was a phantom or an anachronism, subject to chronic insecurity, instability, and ever-deepening impoverishment. Marx and Engels called it "a relic of the sixteenth century." Yet despite cyclical changes in fortune, there is evidence to support the idea that the "middle class society," in terms of individual self-image, personal taste, and material conditions of life, increasingly describes a widespread popular idea of the hoped-for good society.

Such a goal seems at the core of the trade union movement's program. The writings of Marx and Engels even have some inklings of this idea. As they pointed out, among the bourgeoisie's revolutionary qualities is its tendency to replace human labor with machine labor while reducing the amount of human labor time necessary to the production and reproduction processes. We see this today in worldwide advances in technology and communications, in fluctuating and even shrinking labor force participation rates, and in the global trend toward part time, contingent labor.

Some analysts argue that soon the vast majority of people will be unnecessary to the labor process, as machines will do most jobs, or as the idea of work itself will be increasingly defined by its relationship to machines. What this does to our thinking about the difference between "trade union consciousness" and "socialist consciousness" in this context is interesting. Lenin argued that "socialist" consciousness couldn't come from within the trade union movement itself, but had to be brought to the movement from "outside," from a kind of revolutionary intelligentsia. Many socialists disagreed with him at the time, and their critique continues to resonate. Today's trade unions are among the major sources of advanced social consciousness, sometimes relatively, and sometimes absolutely. That's primarily due to nearly two centuries of socialist agitation and education within them; and because the changes in society's organic composition mean that the wage-earning classes include large contingents of highly educated persons whose sophisticated formal learning makes their labor power necessary to today's economy.

What does society do, then, in a world where "work" as we have known it has "disappeared"? (I'm borrowing that phrase from William Julius Wilson [3].) Well, the "disappearance" of work won't stop individual humans from contributing to the general welfare. Today we still think of the relationship between work and reward in antiquated ways, but our thinking has to catch up with our material conditions. That means we have to rethink what "work" is, and demand that we get paid for it; but to do that, we need to think more deeply about questions related to political power.

How we might talk about socialism now

If the "middle class Utopia" I'm discussing here already exists in embryo beneath the surface of contemporary economic and political life, it can only be fully realized in a society that takes so-called "liberal" democracy as its basis, and grows from there. In this regard, I'm reminded of what Engels told the German Social Democrats in 1891 [4]: "If one thing is certain it is that our party and the working class can only come to power under the form of a democratic republic." To see the wage-earning class winning "the battle of democracy" means taking the forms of political participation available in the democratic republic seriously.

This is a special problem for socialists in the United States, who, for much of the movement's existence, have delegated winning power through "electoral" politics - the most legitimate form of politics in our society - to others. Yet as Engels so astutely pointed out, vying for power is the road to power, not perennial protest alone. What is contradictory about this situation is that the main trends within the socialist movement - those rooted in the historic Second and Third Internationals - long ago abandoned reliance on the military-insurrectionary model of social change in favor of a civil insurrectionary and democratic one. This path has long been on their books.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the legendary labor organizer who served as chair of the Communist Party USA in the early 1960s, testified to this fact [5] at her 1952 Smith Act trial. She defended the CPUSA as a "legitimate political party" by narrating its electoral history, including her own 1942 campaign for Congress, where she received 50,000 votes. Yet only in 2016 has a self-proclaimed socialist emerged as a main contender for the most important office of power in the land.

Why this has been the case is not all that clear. The electoral history of the socialist movement in this country has been marred by illegal suppression from officeholders belonging to liberal, pro-capitalist parties, and this engendered and reinforced a deep distrust in the possibilities available at the ballot box. But this alone doesn't explain things. Communists, for example, long considered themselves a different kind of political party, an "activist" party. Socialists of all stripes have often been energetic workers in progressive electoral coalitions.

Yet despite some significant successes, socialist attitudes toward running in elections in their own name ranged from ambivalence to downplaying the importance of elections a path to power, preferring, instead, to see them as educational tools. "We are a party of a new type in that we are not before the people just to capture their votes," Gurley Flynn also told the court. "We are politically active the year round." Besides, socialism often attracted those who were marginal to the status of "citizen" in our country - and for a long time, to be a worker meant you were, effectively, not a citizen. The socialists responded to this problem by building unions and mass voluntary associations, winning elections within these institutions and wielding power and influence through them. This included registering workers to vote and mobilizing them through labor's earliest political action committees. One result of all this was that many of these organizations and institutions became the primary targets of government repression during the McCarthy era.

Yet socialists still believe that deepening the democratic governance over the political sphere, and achieving it over the economic sphere, may be all that stands between civilization and barbarism. Notice, here, that I have been using the word "governance" instead of the word "state." I am mindful that winning the battle of democracy will mostly be fought within the boundaries of single countries. I am also mindful that it can't be won one country at a time. How do we manage democratic governance over global entities in a way that is democratic, effective, beneficial, and peaceful? This is a question for which today's struggles and activists worldwide are urgently seeking an answer, and from the looks of things, this will become one of the fundamental social questions of the current century.

One could say, then, that globalization itself is forcing socialists to return to first principles, as no important social struggle today can be limited to national or even regional borders. Yet gaining social control over the economic life of society - achieving socialism, in a word - requires not only that we know that the democratic republic is the staging ground for such change. It also requires that we recognize that the evidence of the future we want is visible and "invading" our present, to borrow a term from C. L. R. James, in forms that exist in the current conditions of our social life.

Geoffrey Jacques is a poet and critic who has published essays on the visual arts, literature, music, and social issues. His most recent books are Just For a Thrill (Wayne State University Press, 2005), a collection of poetry, and A Change in the Weather: Modernist Imagination, African American Imaginary (University of Massachusetts Press, 2009). He served as a Daily World correspondent in Detroit and New York from 1978-1984. He is currently a culture moderator at Portside. He lives in Southern California.

By

By