This weekend, the G20 leaders' summit takes place – not physically of course, but by video link. Proudly hosted by Saudi Arabia, that bastion of democracy and civil rights, the G20 leaders are focusing on the impact on the world economy from the COVID-19 pandemic.

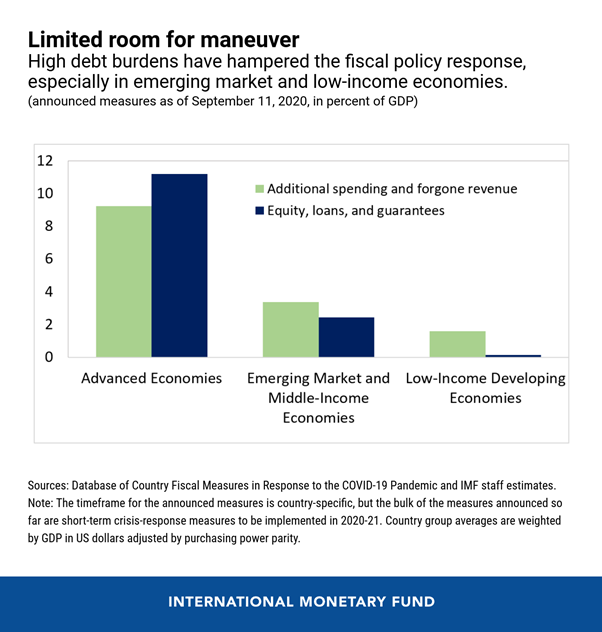

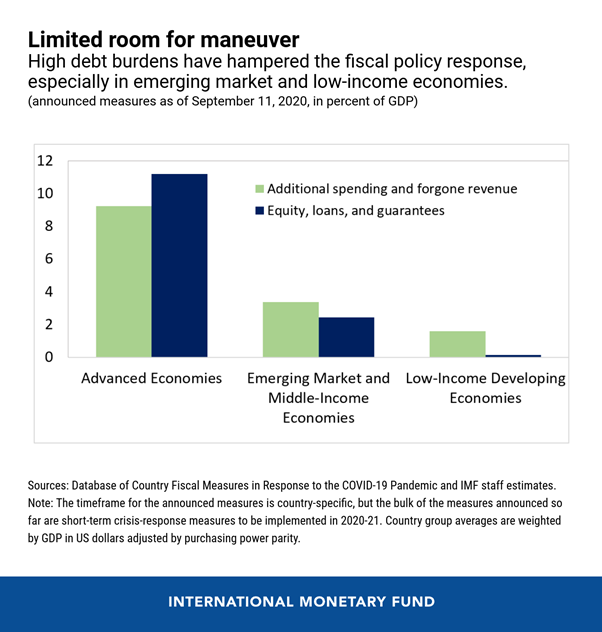

In particular, the leaders are alarmed by the huge increase in government spending engendered by the slump forced on the major capitalist governments to ameliorate the impact on businesses, large and small, and on the wider working population. The IMF estimates that the combined fiscal and monetary stimulus delivered by advanced economies has been equal to 20 per cent of their gross domestic product. Middle income countries in the developing world have been able to do less but they still put together a combined response equal to 6 or 7 per cent of GDP, according to the IMF. For the poorest countries, however, the reaction has been much more modest. Together they injected spending equal to just 2 per cent of their much smaller national output in reaction to the pandemic. That has left their economies much more vulnerable to a prolonged slump, potentially pushing millions of people into poverty.

The situation is getting more urgent as the pain from the pandemic crisis starts to be felt. Zambia this week became the sixth developing country to default or restructure debts in 2020 and more are expected as the economic cost of the virus mounts — even amid the good news about potential vaccines.

The Financial Times commented that: "some observers think that even large developing countries such as Brazil and South Africa, which are both in the G20 group of large nations, could face severe challenges in obtaining finance in the coming 12 to 24 months."

Up to now, very little has been done by the G20 governments to avoid or ameliorate this coming debt disaster. In April, Kristalina Georgieva, the IMF managing director, said the external financing needs of emerging market and developing countries would be in "the trillions of dollars". The IMF itself has lent $100bn in emergency loans. The World Bank has set aside $160bn to lend over 15 months. But even the World Bank reckons that "low and middle-income countries will need between $175bn and $700bn a year".

The only co-ordinated innovation has been a debt service suspension initiative (DSSI) unveiled in April by the G20. The DSSI allowed 73 of the world's poorest countries to postpone repayments. But pausing payments is no solution – the debt remains and even if G20 governments show some further relaxation, private creditors (banks, pension funds, hedge funds and bond 'vigilantes') continue to demand their pound of flesh.

In advanced economies and some emerging market economies, central bank purchases of government debt have helped keep interest rates at historic lows and supported government borrowing. In these economies, the fiscal response to the crisis has been massive. In many highly indebted emerging market and low-income economies, however, governments have had limited space to increase borrowing, which has hampered their ability to scale up support to those most affected by the crisis. These governments face tough choices. For example, in 2020, government debt-to-revenue will reach over 480% across the 35 Sub-Saharan Africa countries eligible for the DSSI.

Even before the pandemic broke, global debt had reached record levels. According to the IIF, in 'mature' markets, debt surpassed 432% of GDP in Q3 2020, up over 50 percentage points year-over-year. Global debt in total will have reached $277trn by year end, or 365% of world GDP.

Much of the increase in debt among the so-called developing economies has been in China where state banks have expanded loans, while 'shadow banking' loans have increased and local governments have carried out increased property and infrastructure projects using land sales to fund them or borrowing.

Many 'Western' pundits reckon that, as a result, China is heading for a major debt default crisis that will seriously damage the Beijing government and the economy. But such predictions have been made for the last two decades since the minor 'asset readjustment' after 1998. Despite the increase in debt levels in China, such a crisis is unlikely.

First, China, unlike other large and small emerging economies with high debts, has a massive foreign exchange reserve of $3trn. Second, less than 10% of its debt is owed to foreigners, unlike countries like Turkey, South Africa and much of Latin America. Third, the Chinese economy is growing. It has recovered from the pandemic slump much quicker than the other G20 economies, which remain in a slump.

Moreover, if any banks or finance companies go bust (and some have), the state banking system and the state itself stands behind ready to pick up the bill or allow 'restructuring'. And the Chinese state has the power to restructure the financial sector – as the recent blockage on the planned launch of Jack Ma's 'finbank' shows. On any serious sign that the Chinese financial and property sector is getting too 'big to fail' , the government can and will act. There will be no financial meltdown. That's not the picture in the rest of the G20.

And most important, globally the rise in debt was not just in public sector debt but also in the private sector, especially corporate debt. Companies around the world had built up their debt levels while interest rates were low or even zero. The large tech companies did so in order to hoard cash, buy back shares to boost their price or to carry through mergers, but the smaller companies, where profitability had been low for a decade or more, did so just to keep their heads above water. This latter group have become more and more zombified (ie where profits were not enough even to cover the interest charge on the debt). That is a recipe for eventual defaults, if and when, interest rates should rise.

What is to be done? One offered solution is more credit. At the G20, the IMF officials and others will push not just for an extension of the DSSI, but also for a doubling of the credit firepower of the IMF through Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). This is a form of international money, like gold in that sense, but instead a fiat currency valued by basket of major currencies like the dollar, the euro and the yen and only issued by the IMF.

The IMF has issued them in past crises and proponents say it should do so now. But the proposal was vetoed by the US last April. "SDRs mean giving unconditional liquidity to developing countries," says Stephanie Blankenburg, head of debt and development finance at Unctad. "If advanced economies can't agree on that, then the whole multilateral system is pretty much bankrupt."

How true that is. But is yet more debt (sorry, 'credit') piled on top of the existing mountain any solution, even in the short term? Why do not the G2 leaders instead agree to wipe out the debts of the poor countries and why do they not insist that the private creditors do the same?

Of course, the answer is obvious. It would mean huge losses globally for bond holders and banks, possibly germinating a financial crisis in the advanced economies. At a time when governments are experiencing massive budget deficits and public debt levels well over 100% of GDP, they would then face a mega bailout of banks and financial institutions as the burden of emerging debt came home to bite.

Recently, the former chief economist of the Bank for International Settlements, William White, was interviewed on what to do. White is a longstanding member of Austrian school of economics, which blames crises in capitalism, not on any inherent contradictions within the capitalist mode of production, but on 'excessive' and 'uncontrolled' expansion of credit. This happens because institutions outside the 'perfect' running of the capitalist money markets interfere with interest and money creation, in particular, central banks.

White puts the cause of the impending debt crisis at the door of the central banks. "They have pursued the wrong policies over the past three decades, which have caused ever-higher debt and ever greater instability in the financial system." He goes on: "my point is: central banks create the instabilities, then they have to save the system during the crisis, and by that they create even more instabilities. They keep shooting themselves in the foot."

There is some truth in this analysis, as even the Federal Reserve admitted in its latest report on financial stability in the US. There has been $7 trillion increase in G7 central bank assets in just eight months in contrast to the $3 trillion increase in the year following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. The Fed admitted that the world economy was in trouble before the pandemic and needed more credit injections: "following a long global recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, the outlook for growth and corporate earnings had weakened by early 2020 and become more uncertain." But while credit injections engendered a "decline in finance costs reduced debt burdens", it encouraged further debt accumulation which, coupled with declining asset quality and lower credit underwriting standards "meant that firms became increasingly exposed to the risk of a material economic downturn or an unexpected rise in interest rates. Investors had therefore become more susceptible to sudden shifts in market sentiment and a tightening of financial conditions in response to shocks."

Indeed, central bank injections have kicked the problem can down the road but solved nothing: "The measures taken by central banks were aimed at restoring market functioning, and not at addressing the underlying vulnerabilities that caused markets to amplify the stress. The financial system remains vulnerable to another liquidity strain, as the underlying structures and mechanisms that gave rise to the turmoil are still in place." So credit has been piled on credit and the only solution is more credit.

White argues for other solutions. He says: "There is no return back to any form of normalcy without dealing with the debt overhang. This is the elephant in the room. If we agree that the policy of the past thirty years has created an ever-growing mountain of debt and ever-rising instabilities in the system, then we need to deal with that."

He offers "four ways to get rid of an overhang of bad debt. One: households, corporations and governments try to save more to repay their debt. But we know that this gets you into the Keynesian Paradox of Thrift, where the economy collapses. So this way leads to disaster." So don't go for 'austerity'.

The second way: "you can try to grow your way out of a debt overhang, through stronger real economic growth. But we know that a debt overhang impedes real economic growth. Of course, we should try to increase potential growth through structural reforms, but this is unlikely to be the silver bullet that saves us." White says this second way cannot work if productive investment is too low because the debt burden is too high.

What White leaves out here is the low level of profitability on existing capital that deters capitalists investing productively with their extra credit. By 'structural reforms', White means sacking workers and replacing them with technology and destroying what's left of labour rights and conditions. That might work, he says but he does not think this will be implemented by governments sufficiently.

White goes on: "This leaves the two remaining ways: higher nominal growth—i.e., higher inflation—or try to get rid of the bad debt by restructuring and writing it off." Higher inflation may well be one option, one that Keynesian/MMT policies would lead to, but in effect it means the debt is paid off in real terms by reducing the living standards of most people. and hitting the real value of the loans made by the banks. The debtors gain at the expense of the creditors and labour.

White, being a good Austrian, opts for writing off the debts. "That's the one I would strongly advise. Approach the problem, try to identify the bad debts, and restructure them in as orderly a fashion that you can. But we know how extremely difficult it is to get creditors and debtors together to sort this out cooperatively. Our current procedures are completely inadequate." Indeed, apart from the IMF-G20 and the rest not having any 'structures' to do this, these leading institutions do not want to provoke a financial crash and a deeper slump by 'liquidating' the debt, as was proposed by US treasury officials during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Instead, the G20 will agree to extend the DSSI payment postponement plan, but not write off any debts. It will probably not even agree to expand the SDR fund. Instead, it will just hope to muddle through at the expense of the poor countries and their people; and labour globally.

-- via my feedly newsfeed