The fantasy world continues. In the US and Europe, stock market index levels are hitting new all-time highs. Bond prices are also near all-time highs. Investment in both stocks and bonds are delivering massive profits for the financial institutions and companies. Conversely, in the 'real' economy, particularly in the productive sectors of industry and transport, the story is dismal. The world's auto industry is in serious decline. Layoffs of workers are on the agenda in most auto companies. The manufacturing sectors in most major economies are contracting.And as measured by the so-called purchasing managers indexes (PMIs), which are indexes of surveys of company managers about the state and prospects for their companies, even the large service sectors are slowing or stagnant.

The latest estimate of US real GDP growth was published yesterday. In the third quarter of this year (June-September), the US economy expanded in real terms (ie after inflation of prices is deducted) at an annual rate of 2.1%, down from 2.3% in the previous quarter. Even though this is modest growth historically, the US economy is doing better than any other major economy. Canada is growing at just 1.6% a year, Japan at just 1.3% a year, the Euro area at 1.2% a year; and the UK at just 1%. The larger so-called 'emerging economies' like Brazil, South Africa, Russia, Mexico, Turkey and Argentina are growing at no more than 1% a year or are even in recession. And China and India have recorded their lowest growth rates for decades. Overall global growth is variously estimated around 2.5% a year, the lowest rate since the Great Recession in 2009.

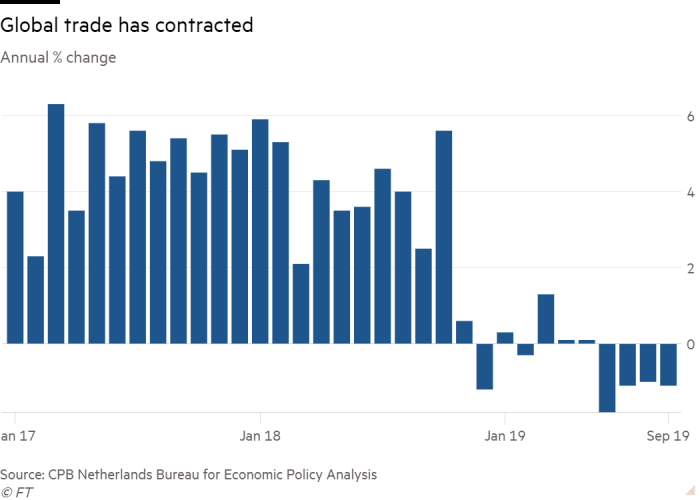

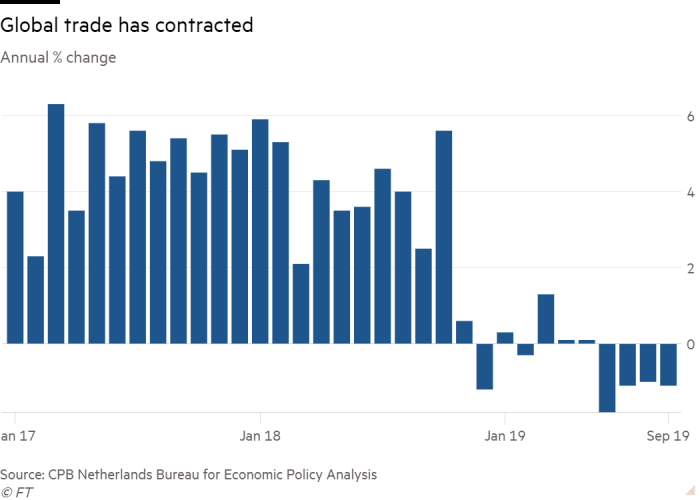

And slowing capitalist economies can find little escape from weak domestic growth by exporting. On the contrary, world trade is contracting. According to data from the CPB World Trade Monitor, in September global trade was down by 1.1 per cent compared to the same month in 2018, marking the fourth consecutive year-on-year contraction and the longest period of falling trade since the financial crisis in 2009.

It's true that unemployment rates in the major economies have plunged to 20-year lows. That has helped maintain consumer spending to some extent.

But it also means that productivity (measured as output divided by employees) is stagnating because employment growth is matching or even surpassing output growth. Companies are taking on workers at unchanged wages rather than investing in labour-saving technology to boost productivity.

According the US Conference Board, globally, growth in output per worker was 1.9 percent in 2018, compared to 2 percent in 2017 and projected to return to 2 percent growth in 2019. The latest estimates extend the downward trend in global labour productivity growth from an average annual rate of 2.9 percent between 2000-2007 to 2.3 percent between 2010-2017. "The long-awaited productivity effects from digital transformation are still too small to see. A productivity recovery is much needed to prevent the economy from slipping towards a substantially slower growth than what has been experienced in recent years."

The Conference Board summarises: "Overall, we have arrived in a world of stagnating growth. While no widespread global recession has occurred in the last decade, global growth has now dropped below its long-term trend of around 2.7 percent. The fact that global GDP growth has not declined even more in recent years is mainly due to solid consumer spending and strong labor markets in most large economies around the world."

The OECD reaches a similar conclusion: "Global trade is stagnating and is dragging down economic activity in almost all major economies. Policy uncertainty is undermining investment and future jobs and incomes. Risks of even weaker growth remain high, including from an escalation of trade conflicts, geopolitical tensions, the possibility of a sharper-than-expected slowdown in China and climate change."

The reason for low real GDP and productivity growth lies with weak investment in productive sectors compared to investment or speculation in financial assets (what Marx called 'fictitious capital' because stocks and bonds are really just titles of ownership to any profits (dividends) or interest appropriated from productive investment in 'real' capital). Business investment everywhere is weak. As a share of GDP, investment in the major economies is some 25-30% lower than before the Great Recession.

Why is business investment so weak? Well, first it is clear the huge injection of cash/credit by central banks and driving of interest rates down to zero – so-called unconventional monetary policies- has failed to boost investment in productive activities. In the US, the demand for credit to invest is falling, not rising.

And for that matter, so far, Trump's cutting of corporate taxes, boosting fiscal spending and running higher budget deficits has failed to restore investment.

In the US, capital spending by S&P 500 companies rose in the third quarter by just 0.8%, or a combined $1.38 billion, from the second quarter, according to data from S&P Dow. But even that modest increase can be chalked up to a few big spenders: Amazon.com Inc. and Apple Inc. alone raised capital spending by $1.9 billion during the quarter. Without them, total spending by the 438 other companies that have reported so far this quarter would have shrunk slightly. And overall spending would have shrunk by 2.2% absent increases from three others: Intel Corp. , Berkshire Hathaway Inc. and NextEra Energy Inc. Together, the five companies increased their capital budgets by $4.7 billion, or 30%, from the second quarter to the third, the SPDJI data show.

The mainstream/Keynesian explanation for low investment was expressed again in a recent blog in the UK Financial Times: "why is fixed investment declining? One answer, dare we suggest it, is a dearth of demand. With no incremental demand for increased supply, why would a business invest in a new plant, shop or regional headquarters when the returns from buying back shares, or distributing dividends, is both known and higher?"

But this explanation is a tautology at best and wrong at worst. First, in what area of demand is there a 'dearth'? Consumer demand and spending is holding up in most major capitalist economies, given fuller employment and even some rise in wages in the last year. It is investment 'demand' that is floundering. But to say that investment is weak because investment 'demand' is weak is just a tautology signifying nothing.

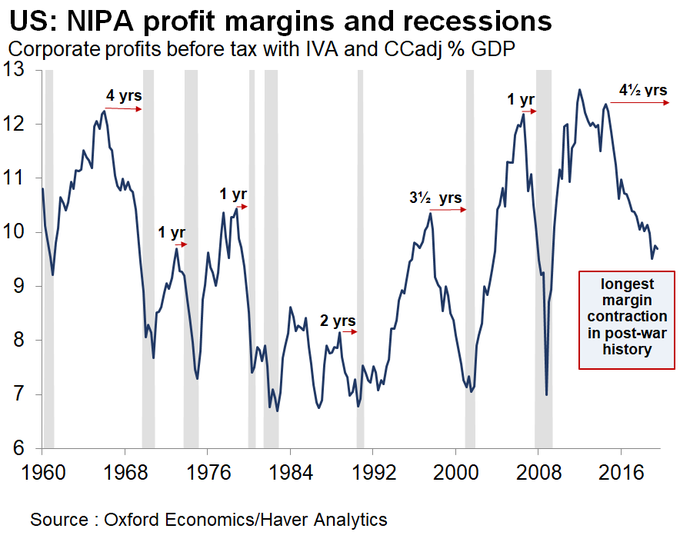

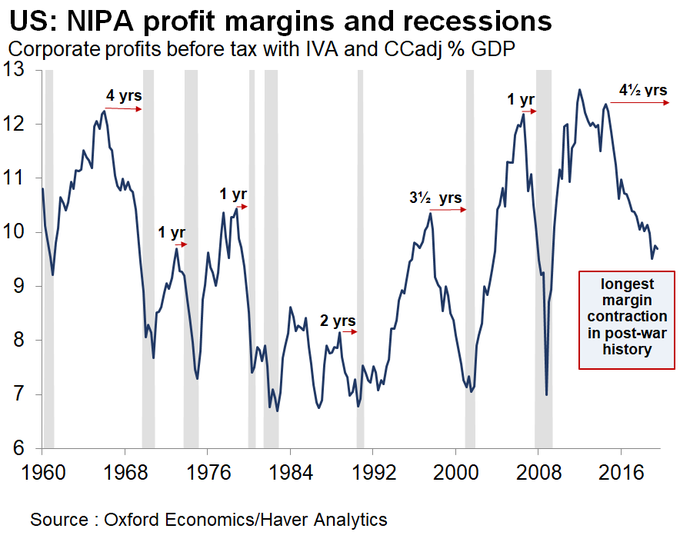

The more explanatory answer offered by Keynesian theory then comes forward. The reason that central bank monetary policies and tax cuts have failed to boost investment "just boils down to risk appetite." This is the classic 'animal spirits' explanation of Keynes. Capitalists have just lost 'confidence' in investing in productive activities. But why? The previous quote above from the FT piece gives it away; "why would a business invest in a new plant, shop or regional headquarters when the returns from buying back shares, or distributing dividends, is both known and higher?" But the returns (profitability) of investing in fictitious capital are higher because the profitability of investing in productive assets is too low. I have explained this ad nauseam in previous posts and papers, along with empirical evidence in support.

In Q3 2019, US corporate profits were down 0.8% from last year while margins (profits per unit of output) remain compressed at 9.7% of GDP – having declined nearly continuously for nearly five years.

But, of course, the failure to recognise or admit the role of profitability in the health of a capitalist economy is common to both mainstream neoclassical and Keynesian theory and arguments.

Low profitability in productive sectors of the most economies has stimulated the switch of profits and cash by companies into financial speculation. The main method used by companies to invest in this fictitious capital has been by buying back their own shares. Indeed, buybacks have become the biggest category of financial asset investment in the US and to some extent in Europe. US buybacks reached nearly $1trn in 2018. That's only about 3% of the total market value of US top 500 stocks, but by boosting the price of their own shares, companies have attracted other investors to push stock market indexes to record highs.

But all good things must come to an end. Returns on fictitious capital investment ultimately depend on the earnings that companies report. And they have been falling in the last two quarters. So in the latter part of this year, corporate buyback spending started to plunge. According to Goldman Sachs, buyback spending slowed 18% to $161 billion during the second quarter, and the firm anticipates that the slowdown will continue. For 2019, total buybacks will drop 15% to $710 billion, and in 2020 GS sees a further 5% decline to $675 billion. "During full-year 2019, we expect S&P 500 cash spending will decline by 6%, the sharpest annual decline since 2009," the firm says.

Anyway, buybacks are an arena dominated by major companies, many of them long-established tech titans. The top 20 buybacks accounted for 51.2% of the total for the 12 months ending in March, S&P Dow Jones Indices states. And more than half of all buybacks are now funded by debt. – "sort of like mortgaging your house to the hilt, then using it to throw a lavish party." But once a recession inevitably arrives, the result may not be pretty for companies with lots of leverage, in no small part due to buybacks.

The market value of tradable U.S. dollar (USD) corporate debt has ballooned to close to $8 trillion – over three times the size it was at the end of 2008. Similarly in Europe, the corporate bond market has tripled to 2.5 trillion euros ($2.8 trillion) since 2008. From 2015-2018, over $800bn of non-financial high grade corporate bonds were issued to fund M&A. This accounted for 29% of all non-financial bond issuance, contributing to credit rating deterioration. And the 'credit quality' of corporate debt is deteriorating with low rated bonds now 61% of non-financial debt, up from 49% in 2011. And the share of BBB-rated bonds in European investment grade has also risen from 25% to 48%.

And then are what are called zombie companies which earn less than the costs of servicing their existing debt and survive because they are borrowing more. These are mainly small companies. About 28% of US companies with market cap <$1bn earn less than their interest payments, way up from the period before the crisis and this is with historically low interest rates. Bank of America Merrill Lynch estimates that there are 548 of these zombies in the OECD against a peak of 626 during the financial crash of 2008.

With corporate debt now higher than its peak in scary late-2008, Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan has warned, overly leveraged companies "could amplify the severity of a recession."

Nevertheless, the talk among many mainstream economists is that the worst may be over. A trade deal between the US and China is imminent. And there are signs that the contraction in the manufacturing sectors of the major economies is beginning to stop. If so, then any 'spillover' into the more buoyant and larger so-called 'service' sectors may be avoided. Global economic growth may be at its slowest since the Great Recession; business investment is sluggish at best; productivity growth is falling; and global profits are flat, but employment is still strong in many economies, and wages are even picking up.

So, far from descending into an outright global recession in 2020, there may be just another year of depressed growth in the longest but weakestglobal recovery for capitalism. And the fantasy world may continue. We shall see.

-- via my feedly newsfeed