Thursday, June 30, 2016

James Zogby: My Role with the Democratic Platform Drafting Committee

My Role With the Democratic Platform Drafting Committee

I wasn't going to write about this subject, but something happened yesterday over lunch that prompted me to reconsider.

I was having a peaceful meal with my wife when two men sat down in the next booth. In loud voices they began to discuss the state of the presidential contest. At one point, the gentleman directly behind me said, "and Sanders picked that Cornel West and that guy who's the head of the Arab League who has it in for Israel...".

That did it. I spun around and said, in a polite but firm voice, "I'm that guy. I'm not the head of the Arab League and I'm asking you to change the subject now." Shocked, the man responded "you're him!" and began asking me questions. I cut him off making it clear that I was having lunch and wasn't interested in pursuing the matter. They promptly changed the subject, as I had requested. After we finished eating, I turned to the two men and explained who I was and why I found the crude description of me to be so aggravating.

In some ways I fault The Washington Post and other mainstream news outlets for having unleashed the mini-firestorm that followed my recent appointment to the Democratic Party's platform drafting committee. When I first heard from DNC Chair

Debbie Wasserman-Schultz that I was to be named to the committee, I held my breath, fully expecting an attack from the usual collection of far-right, anti-Arab, and hardline pro-Israel groups. Sure enough, they didn't disappoint. I was called "a professional Israel-hater", "a defender of terrorism", "Bernie's Svengali", and it was claimed (falsely) that I had "accused Israel of committing a Holocaust".

This, unfortunately, is what I have learned to expect from that crowd. What, however, I found most troubling was the first headline that appeared in The Washington Post announcing "Sanders picks pro-Palestinian activist for Democratic platform committee". With this, the die was cast. Other major newspapers and media outlets followed suit framing the entire discussion of the platform and my appointment around Israel/Palestine—culminating in a call I received yesterday, right after lunch, from a journalist who asked if he was right in assuming that Bernie had appointed me as his hatchet man on this Israel.

I am, of course, a strong supporter of Palestinian rights, so is Bernie Sanders, and so, according to a recent Gallup poll, are a majority of Democrats. But the crude effort to reduce Sanders' entire campaign and my entire life's work to an effort to "get Israel" betrays an unsettling anti-Arab bias and a bizarre obsession to which I must respond. It does damage to Sanders, to me, and to our nation's ability to have an honest conversation about a critical issue of importance.

By focusing exclusively on Israel and ignoring all of the other concerns that Sanders has brought to this year's presidential campaign, the press does a grave disservice to his efforts to elevate the issues of universal health care, free college tuition, raising the minimum wage, investing in clean energy, rebuilding our crumbling infrastructure, and making Wall Street pay its fair share in taxes. This is a not so subtle attempt to demean the man and dismiss his candidacy as marginal.

The same is true for me. In response to the question from the editorial writer as to why Bernie may have appointed me, I recited a bit of my resume. To be sure, I am the proud founder of a number Arab American organizations, but I have also served on the DNC for 23 years. I have been on the DNC Executive Committee for the past 15 years; co-Chaired the DNC Resolutions Committee for the past 10; and have chaired the party's Ethnic Council since 2009. I served as Ethnic Outreach Advisor to both the Gore 2000 and the Obama 2008 Campaigns. And President Obama has twice appointed me to two-year terms on the US Commission on International Religious Freedom.

When the mainstream media and the far-right groups converge in turning my entire life's work into a one-dimensional caricature—"pro-Palestinian activist"—they are not complimenting me. They are setting me up. Make no mistake, I am proud of my advocacy for Palestinian rights, but given the political climate in which we live, such crude reductionism lays the predicate for political exclusion, violence, and threats of violence. Over the years, Arab Americans have suffered from all of these challenges to our rights. I know. I've been there.

When I spoke in favor of a two-state solution in 1988, before this position became fashionable, I was told by Democratic Party leaders "you'll never have a place in this party again". Following that year's convention, Michael Dukakis rejected the endorsement of our Arab American Democratic Federation saying "it was too controversial". When, in 1990, Ron Brown, then Chair of the DNC, came to speak at an Arab American event I was hosting (becoming the first party chair to attend an Arab American event), he told me that he was threatened with a loss of financial support "if you even go into the room with those people".

And then there is the violence. The first time I received a death threat was 1970. My office was fire-bombed in 1980 and after 9/11 three men went to jail for threatening my life and the lives of my children. In every instance, the perpetrators claimed to be striking out for reasons to do with my ethnicity and/or Israel. Now, in the wake of the announcement of my platform committee assignment, the hate mail (but, thank God, no threats) has started up again.

Even beyond this danger, by silencing my community and marginalizing us because we might dare to advocate for Palestinians, there is the damage that this hysteria does to our national discourse. For example, I have been denounced for criticizing Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, but my writings on this subject are not unlike those written by Israelis and some in the American Jewish community. At issue, it appears, is not what we are saying, but that we are the ones saying it. We are accused of "singling Israel out", while in reality it is our critics who are singling out this issue as the only one we cannot discuss.

In addition to all of the other critical issues Bernie Sanders has raised, he has done our nation and the cause of peace a service by bringing the matter of Israel/Palestine into the national debate. It belongs there and deserves to be discussed on its merits, without rancor and without fear. I am proud that Sanders has demonstrated the courage to do this and I am confident that if we work together on the platform committee with openness and mutual respect we can forge a new consensus that reflects the will of the majority of Democrats on all of the critical issues facing our country—including the way forward to articulating the principles that would help us achieve a just and lasting solution to Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Dr. James J. Zogby is the author of Arab Voices (Palgrave Macmillan, October 2010) and the founder and president of the Arab American Institute (AAI), a Washington, D.C.-based organization which serves as the political and policy research arm of the Arab American community.

Harpers Ferry, WV

Geoffrey Jacques: What We Talk about when we talk about socialism

What We Talk About When We Talk About Socialism

A satisfactory answer to the question "What is Socialism?" is harder to find than might seem the case at first glance. One reason for this is that the movement has always toggled between the burden of Utopia and the urgency of the fight for justice. This has been true since its earliest days, when Karl Marx and Frederick Engels wrenched the "socialist" label from the ancient network of counterculture communities and coops they called "Utopian" and then pinned the adjective "scientific" to their own project.

Other than the phrases "to raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class, to win the battle of democracy" that we find in the Communist Manifesto, we have very little from Marx and his early followers about how the socialist dream would be realized. The new society didn't seem to look that much different to Marx than it had to the traditional Utopians, with the distinction between them consisting of squabbles about the means to achieve the goal. For Marx and Engels, socialism would come when "all production has been concentrated in the hands of a vast association of the whole nation." It would be, they wrote, "an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all."

Let's remember that in college Marx was educated in German Idealist philosophy. He seemed to think the proletariat as "the ruling class" would usher in an order governed by reason in Hegel's sense, and by Kant's categorical imperative. This would all take place in a polity that resembles Friedrich Schiller's "Aesthetic State," where "man encounters man" only "as an object of free play." It's a society in which, to again quote Schiller, "to grant freedom by means of freedom is the fundamental law" (italics in the original). Marx's idea of renovating the division of labor, expressed in The German Ideology [1] as "to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic" is not that radically different from Utopia as it has been imagined since Plato's day. When Marx saw what he took to be a real life manifestation of his ideas, in the Paris Commune of the spring of 1871, his account reminded me of descriptions of New England town meetings or of some militant union or movement meetings where the community itself made consequential decisions regarding the allocation of power and resources.

Socialists generally subscribe to the idea that the good society is one in which everybody is actively and decisively involved in allocating power and resources in the cause of advancing the common good. They want a society where the equivalent recognition of difference allows social distinctions between persons to be valued rather than subject to discrimination and the imposition of pariah status. It's a place where each person is motivated by selflessness in a community where people cultivate a state of creative leisure we can associate with the term "living aesthetically," and where each and all are materially rewarded in a way that advances equality.

All of this would also take place in a culture that prizes personal material modesty over decadent wastefulness. W. E. B. Du Bois, in a 1930 Howard University commencement speech, summed up this latter point. "We cannot all be wealthy," he said. "We should not all be wealthy." In an ideal society, he added, "no person should have an income which he does not personally need; nor wield a power solely for his own whim." Just as Du Bois was speaking, the ideology of wealth had generated a worldwide depression and the collapse of capitalist civilization, and war fever was preparing the greatest outbreak of barbarism the world had ever seen. Against this, Du Bois proposed "a simple healthy life on limited income" as "the only responsible ideal of civilized folk."

Socialism's hopeful and problematic past

For a long time one's attitude toward the Bolshevik version of the good society was a thick red marker that placed you in one or another corner of the socialist movement. Feelings among the Communist-led project's sympathizers ranged, but few believed the societies created by the Bolshevik Revolution-inspired movement were perfect. Many saw the police state aspects of these societies as a temporary thing. Meanwhile, governments inspired by Marx and Lenin had gained widespread respect for even attempting what every banker and industrialist knew in his heart was contrary to human nature.

Many of those socialists would today say, about the legacy of Bolshevism in power, that whatever good the Communist-led governments accomplished (a point that itself still generates heated debate), they ended up botching the thing pretty badly. There are lots of reasons for this, and it's an easy enough game to speculate on what went wrong. One explanation I like is that Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin all thought the criminal ethos and the acts that necessarily follow from it could be controlled and put to utilitarian use by the revolutionary party and state.

In a 1920 polemic against Karl Kautsky, Lenin defended this proposition. Kautsky was the leading Marxist theoretician of his age. He co-wrote the 1891 Erfurt Program of the German Social Democratic Party, which provoked a comment from Engels that I will refer to in a moment. Lenin focused on the idea of the "dictatorship of the proletariat." This was an invention of Marx and Engels, but it had increasingly come to be seen - since at least the Erfurt Program - as inappropriate to the task of "winning the battle of democracy." Lenin, however, used this notion to defend the repressive aspects of the Soviet state. He took what had been a waning concept in socialist circles, reshaped it, and turned it into his own.

"The revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat," he wrote [2] in The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky (1920), is "power won and maintained by the violence of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie." Lenin's focus on violence alarmed many of the old-line socialists who felt he included them in his definition of "the bourgeoisie." But it was the words that follow that really set the stage for subsequent history. The "revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat," Lenin claimed, was not just violence, but "power unrestricted by any laws" (emphasis added). That opened the gates to the road to perdition.

It also had two other consequences. It helped cement the split between old-line socialists and the newer Communist movement. There also emerged a kind of split personality among members of the latter group, who, while defending democracy at home, often found themselves with the difficult job of also defending - in the name of "proletarian internationalism" - a Bolshevik-led government when it committed some lawless act. I've often wondered if anybody told the Bolsheviks how the revolutionaries at Philadelphia in 1783, who decided to compromise with the criminal slave power tyranny in their own midst, almost wrecked the fragile Republic they'd created, leaving a legacy that threatens its stability to this day. The Bolsheviks' compromise with the ethos of criminality was a foundational corruption that gravely wounded the socialist dream.

In addition, Communists in power didn't believe in autonomy for civil society institutions. They also didn't believe in the separation of powers. After a violent confrontation between the workers and the Workers' State in Germany in 1953, Bertolt Brecht commented, in his poem "The Solution," on the workers having acted contrary to the revolutionaries' expectations. "Would it not be easier," he asked, "for the government/To dissolve the people/And elect another?" Even now, a quarter of a century after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the role of workers' uprisings in ending the Bolshevik version of the socialist dream is little remarked on by those of us who were part of the movement that Lenin's followers started.

During the Cold War, something else seems to have happened to "labor-management relations," just as the old, smoky industrial society was transitioning into a sleeker, more automated model. Management styles seemed to have had little to do with the essence of the labor-capital relationship itself, hence the workers' strikes against socialism. We still used the terms "capitalist" and "socialist" to describe groups of countries, and "Communist and Workers' Parties" to describe the ruling parties in the latter group, but the "two systems," as they were called, grew to look remarkably alike, and the similarities between them did not go unnoticed. Some intellectuals talked about "convergence" of the two systems, and Herbert Marcuse, the most astute observer of this phenomenon, used the term "advanced industrial civilization" to describe the whole reality. The most peculiar thing was that "advanced industrial civilization" had produced alienated workers and elite managers everywhere while at the same time becoming remarkably collectivized, with the public authority ("the state") regularly intervening in economic matters as umpire, owner, or super-manager. It made no difference what flag pins the managers in the front office wore in their lapels.

This all called into question the nature of "real, existing" socialism. Was it a "separate" system from capitalism, or just a type of industrial society whose modes of meritocratic social mobility and forms of popular political and economic participation and decision-making looked strange from the point of view of those who favored liberal representative democracy? In the end, these questions were rendered moot by the collapse of the Communist-led governments in Europe, and by the reinstitution of modified forms of private property in the means of production and exchange, accompanied by the muting of revolutionary ideology and rhetoric by China and other Bolshevik-inspired countries. These changes threw socialists of all schools into a state of confusion, but it did not remove the fundamental questions or the basic problems that dogged the movement.

Rethinking "class consciousness"

Socialists today still see ourselves as "change agents" (to borrow a term from academia), who work hard to improve society in the here-and-now, hoping this will help the "vast association" of wage earners figure out how to wield power. However, it's still maddeningly difficult for us to describe the new society and how to get there. For one thing, today's capitalism is not our great grandparents' capitalism. To illustrate the point, take The Jungle, the 1906 novel by Upton Sinclair. This is probably the most important socialist and working class novel ever published in this country. The Jungle depicted what was, in 1906, the normal world, and correcting it was often seen as edging around the border between the impossible and the possible. Yet here's the difference. Today we see those same conditions as a violation of norms. Then there are the aspirations of Jurgis Rudkis, the novel's protagonist. Does he just want "socialism," or does he want a better life? And if he wants the latter, does that mean he wants to remain a "worker"? At the heart of these questions lies the conundrum of socialist identity.

Some one hundred years ago, Lenin tried to sever the questions, "what is socialism," and "what does the worker want," from each other. Focusing on the latter question, he argued, was "economism," For him, the only revolutionary form of class consciousness was "socialist" consciousness. Lenin refused to put the "economism" question first. But what if he had? If we try to reunite these two questions and put the "economism" question first, the answer might surprise us. That's because if the wage earners want to raise themselves to the position of the ruling class, only to spend their days raising cattle, hunting, fishing, and criticizing, maybe it means that the working class wants to become something other than a "working class." Maybe the working class wants to liquidate itself as a class, to liquidate classes as such, and to turn the whole of society into a kind of middle class Utopia.

Marx, Lenin, and their followers might have agreed with the first two points, while scoffing at the third one. The "middle class," for them, was a phantom or an anachronism, subject to chronic insecurity, instability, and ever-deepening impoverishment. Marx and Engels called it "a relic of the sixteenth century." Yet despite cyclical changes in fortune, there is evidence to support the idea that the "middle class society," in terms of individual self-image, personal taste, and material conditions of life, increasingly describes a widespread popular idea of the hoped-for good society.

Such a goal seems at the core of the trade union movement's program. The writings of Marx and Engels even have some inklings of this idea. As they pointed out, among the bourgeoisie's revolutionary qualities is its tendency to replace human labor with machine labor while reducing the amount of human labor time necessary to the production and reproduction processes. We see this today in worldwide advances in technology and communications, in fluctuating and even shrinking labor force participation rates, and in the global trend toward part time, contingent labor.

Some analysts argue that soon the vast majority of people will be unnecessary to the labor process, as machines will do most jobs, or as the idea of work itself will be increasingly defined by its relationship to machines. What this does to our thinking about the difference between "trade union consciousness" and "socialist consciousness" in this context is interesting. Lenin argued that "socialist" consciousness couldn't come from within the trade union movement itself, but had to be brought to the movement from "outside," from a kind of revolutionary intelligentsia. Many socialists disagreed with him at the time, and their critique continues to resonate. Today's trade unions are among the major sources of advanced social consciousness, sometimes relatively, and sometimes absolutely. That's primarily due to nearly two centuries of socialist agitation and education within them; and because the changes in society's organic composition mean that the wage-earning classes include large contingents of highly educated persons whose sophisticated formal learning makes their labor power necessary to today's economy.

What does society do, then, in a world where "work" as we have known it has "disappeared"? (I'm borrowing that phrase from William Julius Wilson [3].) Well, the "disappearance" of work won't stop individual humans from contributing to the general welfare. Today we still think of the relationship between work and reward in antiquated ways, but our thinking has to catch up with our material conditions. That means we have to rethink what "work" is, and demand that we get paid for it; but to do that, we need to think more deeply about questions related to political power.

How we might talk about socialism now

If the "middle class Utopia" I'm discussing here already exists in embryo beneath the surface of contemporary economic and political life, it can only be fully realized in a society that takes so-called "liberal" democracy as its basis, and grows from there. In this regard, I'm reminded of what Engels told the German Social Democrats in 1891 [4]: "If one thing is certain it is that our party and the working class can only come to power under the form of a democratic republic." To see the wage-earning class winning "the battle of democracy" means taking the forms of political participation available in the democratic republic seriously.

This is a special problem for socialists in the United States, who, for much of the movement's existence, have delegated winning power through "electoral" politics - the most legitimate form of politics in our society - to others. Yet as Engels so astutely pointed out, vying for power is the road to power, not perennial protest alone. What is contradictory about this situation is that the main trends within the socialist movement - those rooted in the historic Second and Third Internationals - long ago abandoned reliance on the military-insurrectionary model of social change in favor of a civil insurrectionary and democratic one. This path has long been on their books.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the legendary labor organizer who served as chair of the Communist Party USA in the early 1960s, testified to this fact [5] at her 1952 Smith Act trial. She defended the CPUSA as a "legitimate political party" by narrating its electoral history, including her own 1942 campaign for Congress, where she received 50,000 votes. Yet only in 2016 has a self-proclaimed socialist emerged as a main contender for the most important office of power in the land.

Why this has been the case is not all that clear. The electoral history of the socialist movement in this country has been marred by illegal suppression from officeholders belonging to liberal, pro-capitalist parties, and this engendered and reinforced a deep distrust in the possibilities available at the ballot box. But this alone doesn't explain things. Communists, for example, long considered themselves a different kind of political party, an "activist" party. Socialists of all stripes have often been energetic workers in progressive electoral coalitions.

Yet despite some significant successes, socialist attitudes toward running in elections in their own name ranged from ambivalence to downplaying the importance of elections a path to power, preferring, instead, to see them as educational tools. "We are a party of a new type in that we are not before the people just to capture their votes," Gurley Flynn also told the court. "We are politically active the year round." Besides, socialism often attracted those who were marginal to the status of "citizen" in our country - and for a long time, to be a worker meant you were, effectively, not a citizen. The socialists responded to this problem by building unions and mass voluntary associations, winning elections within these institutions and wielding power and influence through them. This included registering workers to vote and mobilizing them through labor's earliest political action committees. One result of all this was that many of these organizations and institutions became the primary targets of government repression during the McCarthy era.

Yet socialists still believe that deepening the democratic governance over the political sphere, and achieving it over the economic sphere, may be all that stands between civilization and barbarism. Notice, here, that I have been using the word "governance" instead of the word "state." I am mindful that winning the battle of democracy will mostly be fought within the boundaries of single countries. I am also mindful that it can't be won one country at a time. How do we manage democratic governance over global entities in a way that is democratic, effective, beneficial, and peaceful? This is a question for which today's struggles and activists worldwide are urgently seeking an answer, and from the looks of things, this will become one of the fundamental social questions of the current century.

One could say, then, that globalization itself is forcing socialists to return to first principles, as no important social struggle today can be limited to national or even regional borders. Yet gaining social control over the economic life of society - achieving socialism, in a word - requires not only that we know that the democratic republic is the staging ground for such change. It also requires that we recognize that the evidence of the future we want is visible and "invading" our present, to borrow a term from C. L. R. James, in forms that exist in the current conditions of our social life.

Geoffrey Jacques is a poet and critic who has published essays on the visual arts, literature, music, and social issues. His most recent books are Just For a Thrill (Wayne State University Press, 2005), a collection of poetry, and A Change in the Weather: Modernist Imagination, African American Imaginary (University of Massachusetts Press, 2009). He served as a Daily World correspondent in Detroit and New York from 1978-1984. He is currently a culture moderator at Portside. He lives in Southern California.

Harpers Ferry, WV

RE: [CCDS Members] Clinton’s Tech Policy Targets Young Entrepreneurs

This kind of talk by any of 'us' is surprising!!! – goes on often "... the only instance (97-98) in 40 years where there was a significant bump in median family income (and wages or salaries)."

Too many people got left out as usual. Prices rose as wages rose.

Norma

From: Members [mailto:members-bounces+normaha=pacbell.net@lists.cc-ds.org] On Behalf Of John Case Sent: Wednesday, June 29, 2016 5:48 AM To: Socialist Economics <socialist-economics@googlegroups.com>; CCDS-Members <members@lists.cc-ds.org>; jcase4218.lightanddark@blogger.com Subject: [CCDS Members] Clinton's Tech Policy Targets Young Entrepreneurs

I will not be surprised if this is the true and principle Clinton structural economic strategy to address inequality: turn more places into Silicon Valleys. It's the strategy, or opportunity, that Bill Clinton exploited in the mid nineties that propelled the tech boom, and the only instance (97-98) in 40 years where there was a significant bump in median family income (and wages or salaries).

I certainly agree that such a strategy can be an important component. But I think its the WRONG focus to put at the TOP of the to-do list. MInimum wage, major infrastructure spending, collective bargaining expansion, big payoffs in the form of cash, new jobs and/or training for displaced workers from globalization and climate change adjustment impacts --- all these things are on top of revisiting the 90s tech boom on MY to-do LIST.

Clinton's Tech Policy Targets Young Entrepreneurs

By STEVE LOHRJUNE 28, 2016

Hillary Clinton's technology policy initiative, released on Tuesday, is a list maker's dream, a parade of specific proposals covering a spectrum of issues. But its overriding theme is that technology should be an engine of equality rather than elitism.

The goal, the summary document declares, is "to create the jobs of the future on Main Street."

Mrs. Clinton's agenda includes having the federal government step in to help fill a finance gap, as banks have cut their loans to small businesses and venture capital funding is concentrated in a few regions, led by Silicon Valley.

Her plan calls for "supporting incubators, accelerators, mentoring and training for 50,000 entrepreneurs in underserved areas," and increasing funding for several existing programs that offer tax credits and financing for community development and small businesses.

"This is a pragmatic plan that could help leverage what happens in Silicon Valley so that there's innovation and job growth throughout the country," said Karen Kornbluh, former United States ambassador to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, who is an adviser to the Clinton campaign.

The Clinton program also links start-ups with the student loan crisis. Under her plan, young entrepreneurs could defer payments on their federal student loans for up to three years. The relief might also apply to the early employees of start-ups, like the first 10 or 20 workers, according to the plan.

The deferred payment plan, the campaign document states, could mean that "millions of young Americans" would not have to pay interest or principal on their loans "as they work through the critical start-up phase of new enterprises."

It is clearly a nod to young voters, who overwhelmingly supported Bernie Sanders in the primaries.

The Clinton plan offers a liberal immigration initiative that has long been a favorite of technology executives and venture capitalists: automatically issuing permanent resident status to people who earn graduate degrees in science, engineering and mathematics from accredited universities.

The Clinton program also would dedicate additional funding and resources to Obama administration policies in areas like building broadband networks in rural areas, encouraging computer science education for elementary and high school students, and job training in technology fields.

Skeptics questioned spending to "double down" on programs that have not yet proved effective.

"No one seems to be evaluating these programs," said Thomas Lenard, president of the Technology Policy Institute, a nonprofit research foundation.

Jeffrey Eisenach, a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning policy research group, said, "This isn't a technology plan, it's a government spending plan."

But other technology policy experts were impressed by the Clinton campaign document as a whole.

"She's got a technology and innovation agenda, and this suggests it would be a strong focus in a Clinton presidency," said Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a nonprofit policy research group. "That in itself is a message."

John Case

Harpers Ferry, WV

The Winners and Losers Radio Show

7-9 AM Weekdays, WSHC-Listen Live, Shepherd University

Sign UP HERE to get the Weekly Program Notes.

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

Jesse Jackson: What Hillary Clinton should learn from Brexit [feedly]

Brexit - the stunning British vote to leave the European Union - is a clear and dramatic rebuke of the country's political and economic elites. A majority voted to leave even though the heads of the United Kingdom's two major parties, more than a thousand corporate and bank CEOs, legions of economists, the leaders of Europe and the United States, and the heads of the international financial organizations all warned of dire consequences if they did not vote to remain.

For Americans, one question is whether this result has implications for the 2016 presidential campaign. Political sea changes tend to cross national boundaries. Ronald Reagan's election in 1980 tracked the rise of Margaret Thatcher to power in Great Britain. Bill Clinton's New Democrats were mirrored by Tony Blair's New Labour Party. So does Brexit presage the rise of Donald Trump in the United States?

The Leave campaign slogan - "Take back control" - is mirrored by Trump's "Make America great again." The same economic insecurities, the sense of the system being rigged, the racial fears and the anger at immigrants that fueled the Leave campaign have elevated Trump's candidacy. Like Trump, the Leave campaign expressed its scorn for experts and politicians. Like Trump, the campaign told a clear story to voters about how they got in the fix they are in, and who is to blame.

In Britain, the vote divided along the lines of education, class and age. The better educated, more affluent and younger voted to stay. The less educated, less affluent and older voted to get out. Those campaigning to leave made appeals based on sovereignty, race and nativism. They campaigned against unaccountable bureaucrats and disdainful elites who rigged the system against working people. What surprised pollsters was the strong turnout by non-college educated, older working people, who lined up to register their discontent.

There is a clear warning here for Hillary Clinton. She is the quintessential establishment candidate, having been in Washington for the last 25 years. She has presented herself as a continuation of the Obama years. Her experience and expertise are universally acknowledged. But she is the candidate of the status quo at a time when people are looking for change.

Our political and economic elites tend to be in denial. They profit from globalization, take pride in the exercise of American power abroad, live in affluent communities, and often are closer to their international peers than to their poorer neighbors. They don't see the America that has been ravaged by our ruinous trade policies. They avoid the killing streets of our impoverished urban neighborhoods. They were shaken by the Great Recession but largely have recovered. They don't see that most Americans have lost ground over the course of this century. They simply don't understand the scope of their failure to make this system work for working people - for the majority of Americans.

The Brexit vote showed that it is not enough to scorn the lies, exaggerations and divisive racial appeals of a demagogue. The Remain vote in Britain was explicitly a status quo vote - the EU isn't great, it seemed to say, but it is what we've got and our elites and experts say change would be catastrophic. But when people feel that the elites have failed them, that the system has been rigged to favor the few, that things are getting worse, not better, the invocation of authority in defense of the status quo loses force. People want to know what you will do to make things better. You've got to be able to tell a more convincing story that explains how we got where we are, who is to blame and what can be done about it. This is a lesson that Clinton surely understands.

The Brexit vote also reveals the comparative strength of the Democratic coalition here in the United States. Young people in Britain voted overwhelmingly against leaving; young people here will not vote for Trump. Minorities and immigrants - a much smaller portion of the population in Britain - voted against leaving; minorities here will not vote for Trump's racist politics. The question is only whether the young and minorities will turn out in large numbers or whether, uninspired, they will stay home in large numbers. Turning them out also requires a campaign that gives them hope for a change, not simply a promise of more of the same.

Brexit is a warning. There will be a reckoning. A divisive demagogue like Trump can profit in such times, but the politics of inclusion can beat the politics of division - but only by offering people a new deal that gives them hope.

Rev. Jesse Jackson is the founder and president of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition. He was a leader in the civil rights movement alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and was twice a candidate for President of the United States.

This article originally appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times. It is reprinted here with the permission of Rainbow PUSH.

Photo: British Prime Minister David Cameron meets with then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in London in 2012. (U.S. Embassy in the United Kingdom)

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Clinton’s Tech Policy Targets Young Entrepreneurs

Clinton's Tech Policy Targets Young Entrepreneurs

By STEVE LOHRJUNE 28, 2016

Hillary Clinton's technology policy initiative, released on Tuesday, is a list maker's dream, a parade of specific proposals covering a spectrum of issues. But its overriding theme is that technology should be an engine of equality rather than elitism.

The goal, the summary document declares, is "to create the jobs of the future on Main Street."

Mrs. Clinton's agenda includes having the federal government step in to help fill a finance gap, as banks have cut their loans to small businesses and venture capital funding is concentrated in a few regions, led by Silicon Valley.

Her plan calls for "supporting incubators, accelerators, mentoring and training for 50,000 entrepreneurs in underserved areas," and increasing funding for several existing programs that offer tax credits and financing for community development and small businesses.

"This is a pragmatic plan that could help leverage what happens in Silicon Valley so that there's innovation and job growth throughout the country," said Karen Kornbluh, former United States ambassador to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, who is an adviser to the Clinton campaign.

The Clinton program also links start-ups with the student loan crisis. Under her plan, young entrepreneurs could defer payments on their federal student loans for up to three years. The relief might also apply to the early employees of start-ups, like the first 10 or 20 workers, according to the plan.

The deferred payment plan, the campaign document states, could mean that "millions of young Americans" would not have to pay interest or principal on their loans "as they work through the critical start-up phase of new enterprises."

It is clearly a nod to young voters, who overwhelmingly supported Bernie Sanders in the primaries.

The Clinton plan offers a liberal immigration initiative that has long been a favorite of technology executives and venture capitalists: automatically issuing permanent resident status to people who earn graduate degrees in science, engineering and mathematics from accredited universities.

The Clinton program also would dedicate additional funding and resources to Obama administration policies in areas like building broadband networks in rural areas, encouraging computer science education for elementary and high school students, and job training in technology fields.

Skeptics questioned spending to "double down" on programs that have not yet proved effective.

"No one seems to be evaluating these programs," said Thomas Lenard, president of the Technology Policy Institute, a nonprofit research foundation.

Jeffrey Eisenach, a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning policy research group, said, "This isn't a technology plan, it's a government spending plan."

But other technology policy experts were impressed by the Clinton campaign document as a whole.

"She's got a technology and innovation agenda, and this suggests it would be a strong focus in a Clinton presidency," said Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a nonprofit policy research group. "That in itself is a message."

Harpers Ferry, WV

Rising Income Polarization in the United States

Rising Income Polarization in the United States

By Ali Alichi

By Ali Alichi

The latest IMF review of the U.S. economy underscores the country's resilience in the face of financial market volatility, a strong dollar, and subdued global demand. But the review also cites longer-term challenges to growth, including rising income polarization.

Ever since the 1970s, the number of U.S. middle-income households, as percent of total, has been shrinking. The result has been increasing income polarization. For the three initial decades since then this polarization was more about households moving into the upper income ranks. However, since 2000, more middle-income households have fallen into lower, rather than higher income brackets. Combined with real income stagnation, polarization has had a negative impact on the economy, hampering the main engine of the U.S. growth: consumption. The analysis in our new paper suggests that over 1998–2013, the U.S. economy has lost the equivalent of more than one year of consumption growth due to increased polarization.

Importance of middle-income households

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle observed that "the most perfect political community is one in which the middle class is in control, and outnumbers both of the other classes." More than two thousand years later, most would still agree with that idea. For all its importance, notwithstanding some studies in the 1980s and a handful of recent contributions, economists have fallen behind in documenting the progress being made by middle-income households, their consumption patterns, and other economic behavior. More analysis is needed on the economic policies that could affect middle-income households by spurring the upward mobility of low and middle income earners. Part of the problem has been that we do not have any stable conventions on how best to define middle-income households.

Our work seeks to address some of these issues and energize this line of empirical research, focusing specifically on the movement of middle-income households up or down the income ladder, and the economic effects of these moves. While income inequality has attracted much attention, income polarization has yet to receive as much examination. There is a conceptual and qualitative difference between the two: income polarization measures the move from the middle of the income distribution out into the tails; income inequality, however, measures how far apart those tails are, i.e., what is the income distance between the low- and high-income groups.

Worrying trend

Middle-income households serve as a point of reference in any discussion of income polarization, and should, therefore, be well defined. Here, middle-income households are defined as those whose real incomes are within 50 to 150 percent of the median income. Households with incomes below this range are viewed as low income and above it, high income. Chart 1 shows that the population share of middle-income households has shrunk from about 58 percent of total in 1970 to 47 percent in 2014. Such a shift, in part, represents economic progress as roughly half of these households have been able to advance up through the income distribution, while the other half have moved down. Looking at the long trends, however, masks the deteriorating trends since the turn of the current century. While during 1970–2000, more of the middle-income households moved into high- rather than low-income ranks, since 2000 only a quarter of one percent of households have moved up to high income ranks, compared to an astonishing 3¼ percent of households who have moved down the income ladder (from middle to low-income ranks).

These polarization trends are robust to different cut-offs in defining the middle-income households. In addition, excluding households at the top 1 percent of income distribution or looking at households across age, race, or education still produces the same result.

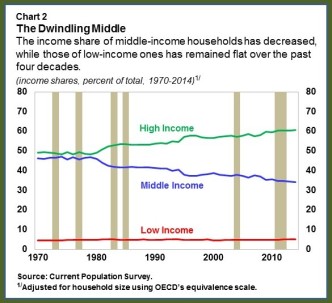

In addition to the polarization trends, it would be also important to look at the income shares of different income groups—a proxy for their relative weights in the economy. Chart 2 shows that income shares have also had a similar trend as polarization trends. The income share of the middle-income households, which was about 47 percent of total income in 1970, had fallen to about 35 percent in 2014. That decrease in the income of the middle-income households corresponds to the increase in the income share of the high-income households. Meanwhile, the income share for the lower-income households has remained flat over the entire period at around 5 percent of total national income. Low wage growth in recent years—partly a result of the drawn out recovery but also because of lower labor market dynamism—has also contributed to these trends.

The macroeconomic consequences of rising polarization

Income polarization, insofar as it disproportionately moves households toward the lower part of the income distribution, may have negative social and political repercussions and simply be seen as unfair.

But polarization can also have important macroeconomic consequences. Low- and middle-income households spend a far larger share of their income than high-income households—to use economists' jargon, the low- and middle-income households have higher marginal propensities to consume. Therefore, any loss of income in these two groups has the potential to lower the U.S. economy's aggregate consumption. Given the smaller propensity to consume by higher income groups, they can only provide a partial offset.

To make matters worse, evidence suggests that, after controlling for income levels, the responsiveness of consumption to income gains for most of the income distribution has weakened in recent years. This puts further downward pressure on consumption. Combined, these effects are estimated to translate to about 3½ percentage points of lost U.S. consumption over 1998–2013—equivalent to more than one year of total consumption growth.

To sum up: income polarization in the United States has seen a significant increase since the 1970s. While initially more middle-income households moved up the income ladder rather than down, since 2000, most of the increased polarization has been towards the low end of the income ladder. These trends, in addition to the well-documented income inequality trends, have led to a declining income share of the middle-income households. This has important macroeconomic consequences and merits receiving increasing attention and analysis in the coming years. Further research is needed to understand what are the root causes of income polarization and devise policies to mitigate the pattern, ensure the bulk of the population is achieving improved living standards over time, and tackle the social and macroeconomic consequences of polarization toward the lower part of the income distribution.

Harpers Ferry, WV

Inequality Has Grown in All 50 States [feedly]

http://www.cbpp.org/blog/inequality-has-grown-in-all-50-states

The gaps between the richest and poorest families have grown in every state since the late 1970s, a new report from the Economic Policy Institute shows. The top 1 percent's share of income is close to its 1928 peak (see chart).

The report's alarming findings include:

- In 2013, the average income of the top 1 percent of families nationally was $1.2 million — more than 25 times the average income of the bottom 99 percent.

- The lion's share of income growth since the late 1970s has gone to the richest households.

- The top 1 percent's share of income rose in every state and the District of Columbia — and it doubled nationally, from 10 percent to 20 percent — between 1979 and 2013.

- Since 2007, due to the Great Recession, family income at all levels has fallen and income gaps narrowed somewhat. On the other hand, the richest families have benefitted most from the economic recovery. In 24 states, the top 1 percent captured at least half of all income growth between 2009 — the year the recession officially ended — and 2013.

I'll be back tomorrow with some steps that states can take to push back against this extreme income inequality

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Bernanke on Economic implications of Brexit [feedly]

http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/ben-bernanke/posts/2016/06/28-brexit

After several days of market upset, a few reflections on last week's momentous vote in Great Britain.

Even more obvious now than before the vote is that the biggest losers, economically speaking, will be the British themselves. The vote ushers in what will be several years of tremendous uncertainty—about the rules that will govern the U.K.'s trade with its continental neighbors, about the fates of foreign workers in Britain and British workers abroad, and about the country's political direction, including perhaps where its borders will ultimately lie. Such fundamental uncertainty will depress business formation, capital investment, and hiring; indeed, it had begun to do so even before the vote. The U.K. economic slowdown to come will be exacerbated by falling asset values (houses, commercial real estate, stocks) and damaged confidence on the part of households and businesses. Ironically, the sharp decline in the value of the pound may be a bit of a buffer here as, all else equal, it will make British exports more competitive.

In the longer run, the uncertainty will dissipate, but the economic costs to the U.K. still will exceed the benefits. Financial services and other globally oriented industries, which depend on unfettered access to European markets and exchanges, will come under pressure. At the same time, the purported gains from freeing the U.K. from the heavy regulatory hand of Brussels will be limited, because Britain will likely have to accept most of those rules (without ability to influence them) as part of restructured trade agreements. Immigration is unpopular in the U.K., and slowing it was a motivation for some "leave" voters, but a more slowly growing labor force likely would also reduce overall economic growth.

The rest of Europe will also be adversely affected, even though Frankfurt and a few other cities may gain finance jobs at the expense of London. The biggest risks here are political, as has been widely noted: In particular, markets are already beginning to price in the risk that other countries or regions will press for greater autonomy from Brussels. Even those sympathetic to such demands should worry that attempts to unwind existing trade and regulatory arrangements could be highly disruptive, as they will likely be for Great Britain. A move toward exit by a member of the euro zone would be particularly destabilizing, as even the possibility that a country might leave the common currency could provoke bank runs and speculative attacks on the country's sovereign debt and on other countries that might be thought to be next in line. The challenge for European leaders will be to keep the overall integration process on track, while finding ways to meet the concerns of potential leavers. One issue that could be revisited is the EU's commitment to the absolutely free movement of people across borders, which seems more a political than an economic principle; the perception that the U.K. had lost control of its borders was one of the most effective arguments for "leave," and secessionist movements elsewhere have also seized on the issue. [1]

Globally, the Brexit shock is being transmitted mostly through financial markets, as investors sell off risky assets like stocks and flock to supposed safe havens like the dollar and the sovereign debt of the U.S., Germany, and Japan. Investors are perhaps more risk-averse than they otherwise would be because they know that advanced-economy central bankers have less space than in the past to ease monetary policy. Among the hardest hit countries is Japan, whose battle against deflation could be set back by the strengthening of the yen and the decline in Japanese equity prices. In the United States, the economic recovery is unlikely to be derailed by the market turmoil, so long as conditions in financial markets don't get significantly worse: The strengthening of the dollar and the declines in U.S. equities are relatively moderate so far. Moreover, the decline in longer-term U.S. interest rates (including mortgage rates) partially offsets the tightening effects of the dollar and stocks on financial conditions. However, clearly the Fed and other U.S. policymakers will remain cautious until the effects of the British vote are better sorted out.

Although bank stock prices are taking hits, especially in the U.K. and Europe, a financial crisis seems quite unlikely at this point. Central banks are monitoring the funding and financial conditions of banks, and so far serious problems have not emerged. (It helps that the date of the referendum has been known for months, giving authorities time to prepare. Also helpful is the substantial buildup in bank capital in recent years.) Through its currency swap lines, established during the global financial crisis, the Fed is making sure that other major central banks have access to dollars. As I've already suggested, the biggest risks to financial stability at this point appear to be political—specifically, the risk of further defections or breakdown in the European Union—rather than economic. The story may not be over yet.

[1] Britain has substantial immigration from both EU and non-EU countries. The debate over Brexit sometimes seemed to confound the two, even though only the former is protected by the EU treaties.

Comments are welcome, but because of the volume, we only post selected comments.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

NYTimes: Bernie Sanders: Democrats Need to Wake Up

Here's a story from The New York Times I thought you'd find interesting:

The rejection of globalization that powered the Brexit movement could happen in the United States. And it may help Donald J. Trump.

Read More: http://nyti.ms/29cQUeS

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Brexit: The end of globalization as we know it? [feedly]

----

Brexit: The end of globalization as we know it?

// Economic Policy Institute Blog

The British vote to leave the European Union is a watershed event—one that marks the end of an era of globalization driven by deregulation and the ceding of power over trade and regulation to international institutions like the EU and the World Trade Organization. While there were many contributing factors, the 52 percent vote in favor of Brexit no doubt in part reflects the fact that globalization has failed to deliver a growing standard of living to most working people over the past thirty years. Outsourcing and growing trade with low-wage countries—including recent additions to the EU such as Poland, Lithuania, and Croatia, as well as China, India and other countries with large low-wage labor forces—have put downward pressure on wages of the working class. As Matt O'Brien notes, the result has been that the "working classes of rich countries—like Brexit voters—have seen little income growth" over this period. The message that leaders in the United Kingdom, Europe, and indeed the United States should take away from Brexit is that the time has come to stop promoting austerity and business-as-usual trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (and the now dead Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership) and to instead get serious about rebuilding manufacturing and an economy that works for working people.

Conservative austerity policies in Britain over the past two decades, which have slashed government spending and limited government's ability to deliver public services and support job creation, fueled the anger towards elites that encouraged Brexit. At the same time, the neoconservative, anti-regulatory views of public officials in Brussels—who are disdainful of government intervention in the economy and who consistently pushed for the "liberalization of labor markets" and other key elements of the neoconservative model—left Europe unprepared for the Great Recession. It's no surprise, then, that there has been a revolt against the EU. When the financial crisis hit in 2008, EU authorities, especially banking officials in Germany and other wealthy countries that have a dominant influence over the European Central Bank, reacted by blaming public officials in Greece, Spain, Portugal and other countries hardest hit by the crisis. The budget cuts they demanded led to further contractions in spending and soaring unemployment which still persists in much of southern Europe, putting further downward pressure on employment in the UK and setting the stage for widespread populist revolts from the left and right that have gained traction across much of Europe.

----

Shared via my feedly newsfeed

Acemoglu et al:State capacity and American technology: Evidence from the 19th century

State capacity and American technology: Evidence from the 19th century

Daron Acemoglu, Jacob Moscona, James A Robinson 27 June 2016

The 'great inventions' view of productivity growth ascribes the excellent growth from 1920 to 1970 in the US to a handful of advances, and suggests that today poor productivity performance is driven by a lack of breakthrough discoveries. This column argues instead that the development of an effective governmental infrastructure in the 19th century accounted for a major part of US technological progress and prominence in this period. Infrastructure design thus appears to have the power to reinvigorate technological progress.

Related

- Peter H. Lindert, Jeffrey G. Williamson

- Francisco Buera, Ezra Oberfield

- Robert J. Gordon

- Jeremiah Dittmar

Robert Gordon's new book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, argues that rapid technological progress in the US economy between 1920 and 1970 was a result of the availability of 'great inventions' that had the potential to drastically change the way individuals lived their lives (Gordon 2016, p. 2). Present day economic growth is slower because inventions that have the transformative power of electricity and the internal combustion engine are no longer emerging.

This perspective runs counter to approaches that emphasise how the pace and direction of technological change respond to incentives and opportunities, often shaped by the institutional environment and policy decisions (see Acemoglu 2009 for an overview).

- Patents, property rights and functioning judicial institutions, for instance, allow individuals to reap the rewards of their investments and new ideas;

- Educational institutions and policies and a legal environment ensuring lack of discrimination against specific groups are also key for opportunities in business as well as in innovation to be open to most individuals in society; and

- Subsidies for research and development or tax credits are important for innovation incentives as well.

These factors have not only been shown to be important in general, but also to have played a critical role in 19th century American innovation (e.g. Sokoloff 1988, Khan 2005).

In a recent working paper, we empirically tests the hypothesis that the US government's infrastructural capacity helped drive innovation during the 19th century (Acemoglu et al. 2016). Our results suggest that, notwithstanding the view that the American state was weak in the 19th century, a major part of the explanation for US technological progress and prominence is the way in which the US developed an effective state.

State capacity and the Post Office

We measure state capacity by making use of the fact that during this period one of the most widespread and instrumental federal institutions was the post office, established by the Post Office Act of 1792. By 1816, 69% of the federal civilian workforce were postmasters and by 1841 the figure had grown to 79% (John 1995, p. 4). According to John (1895), "[F]or the vast majority of Americans the postal system was the federal government" (p. 4, italics in original).

The scale and significance of the post office during the 19th century was noted by its contemporary observers as well. In his famous travels through the US, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote, "There is an astonishing circulation of letters and newspapers among these savage woods… I do not think that in the most enlightened districts of France there is an intellectual movement either so rapid or on such a scale as in this wilderness" (de Tocqueville 1969, p. 283). In 1852, the New York Timesdescribed the post office as the "mighty arm of the civil government" (John 1995, p. 10). In the spirit of the empirical approach in Acemoglu et al. (2015), we use the number of post offices in a county as a proxy for the general infrastructural power and presence of the state, and argue that it was this state presence – not just good timing, randomness, or external factors – that made 19th century innovation and patenting feasible and desirable.

Using historical records compiled by the US Postmaster General, we determined how many post offices were in each US county for several years between 1804 and 1899.1 As a measure of county-level innovative activity, we use the number of patents granted to inventors living in the county (these data are presented in Akcgit et al. 2013).2 There are several reasons for expecting the number of post offices to impact the number of patent grants. First, post offices facilitated the spread of ideas and knowledge. Second, more prosaically, the presence of a post office made patenting much easier, in part because patent applications could be submitted by mail free of postage (Khan 2005, p. 59). Third, the presence a post office is indicative of – and thus the proxy for – the presence and functionality of the state in the area. This expanded state capacity may have meant greater access to legal services and regulation, or greater security of other forms of property rights, all of which are essential conditions for modern innovative activity.

New results

We find a significant correlation between a history of state presence – using the number of post offices as a proxy – and patenting in US counties. We show that the correlation holds either using a sample of the 935 US counties that had been established by 1830, or using a sample to which counties are added as they were established between 1830 and 1890, ultimately reaching 2,644 in total.3 This relationship is not only statistically significant, but also economically meaningful. Our results suggest that the opening of a post office in a county that did not previously have a post office or patents on average increased the number of patents by 0.18 in the long run.

We subject these results to a series of robustness checks. In addition to county and year fixed effects included in all regressions, we control flexibly for a broad range of initial county characteristics – the fraction of the population that were slaves in 1860, the fraction of the adult population that was literate in 1850, and the values of farm and manufacturing output relative to population in 1850. Despite the inclusion of these 36 controls, the relationship between post offices and patenting remains highly significant. We also include county-level linear trends to check that differential county-level trends do not explain our results.

One concern with this initial set of results might be that they are confounded by the possibility that post offices were built in counties that already had more patenting activity. Though we cannot fully rule out such reverse causality concerns, we find no statistically or economically significant correlation between patenting and the number of post offices in a county in future years. This suggests that post offices led to patenting and not the other way around. Historical evidence also suggests that post offices were established for a range of idiosyncratic reasons during the 19th century, making it unlikely that reverse causality is driving the association. John (1995) [A8] notes that pressure for the state's services from certain segments of society "guaranteed that the postal network would expand rapidly into the trans-Appalachian West well in advance of commercial demand" (p. 44-5). In his early history of the US Post Office, Cushing (1893)[A9] wrote that post offices were often established in US territories before the territories were formally settled:

"The establishment of post offices in Oklahoma and in other regions recently opened has often been in advance of actual settlement. Before Oklahoma counties were named they were called by the Department A, B, C, D, E, etc. … Postmasters were appointed upon recommendations of the delegate from Oklahoma and of Senators Plumb, Paddock, and Manderson" (p. 286).

In this context, it seems improbable that post office construction followed patenting activity.

Taken together – while we do not establish unambiguously that the post office and greater state capacity caused an increase in patenting – our results highlight an intriguing correlation and suggest that the infrastructural capacity of the US state played an important role in sustaining 19th century innovation and technological change. In the current economic climate in which pessimism about US economic growth prospects is common, we present a more optimistic historical narrative in which government policy and institutional design have the power to support technological progress.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2009), Introduction to Modern Economic Growth, Princeton University Press

Acemoglu, D., C. Garcia-Jimeno and J. Robinson (2015) "State Capacity and Economic Development", American Economic Review, 105 (8), 2364-2409

De Tocqueville, A. (1969), Democracy in America, ed. J P Mayer, Garden City, Doubleday & Co.

Gordon, R. J. (2016), The Rise and Fall of American Growth, forthcoming, Princeton University Press.

Endnotes

[1] The years for which we were able to obtain county-level post office data are 1804, 1811, 1819, 1830, 1837, 1846, 1850, 1855, 1867, 1870, 1879, 1891, and 1899. For the years before 1879, we used United States Post Office Department publications titled List of the Post Offices in the United States (in some years, the publication was referred to as Table of Post Offices in the United States). In 1874, the federal government began publishing post office information more systematically in a publication titled The United States Postal Guide, which is digitised only for some years. This publication is our source for the years 1879, 1891, and 1899.

[2] We are grateful to Tom Nicholas for sharing these data.

[3] The former results in a balanced panel of counties while the latter is an unbalanced panel in which counties are included in the data only for the years after their establishment.

Harpers Ferry, WV

West Virginia GDP -- a Streamlit Version

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.

-

John Case has sent you a link to a blog: Blog: Eastern Panhandle Independent Community (EPIC) Radio Post: Are You Crazy? Reall...

-

---- Mylan's EpiPen profit was 60% higher than what the CEO told Congress // L.A. Times - Business Lawmakers were skeptical last...

-

via Bloomberg -- excerpted from "Balance of Power" email from David Westin. Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the late...