It Stops Being Scary When Its the Only Light Around.

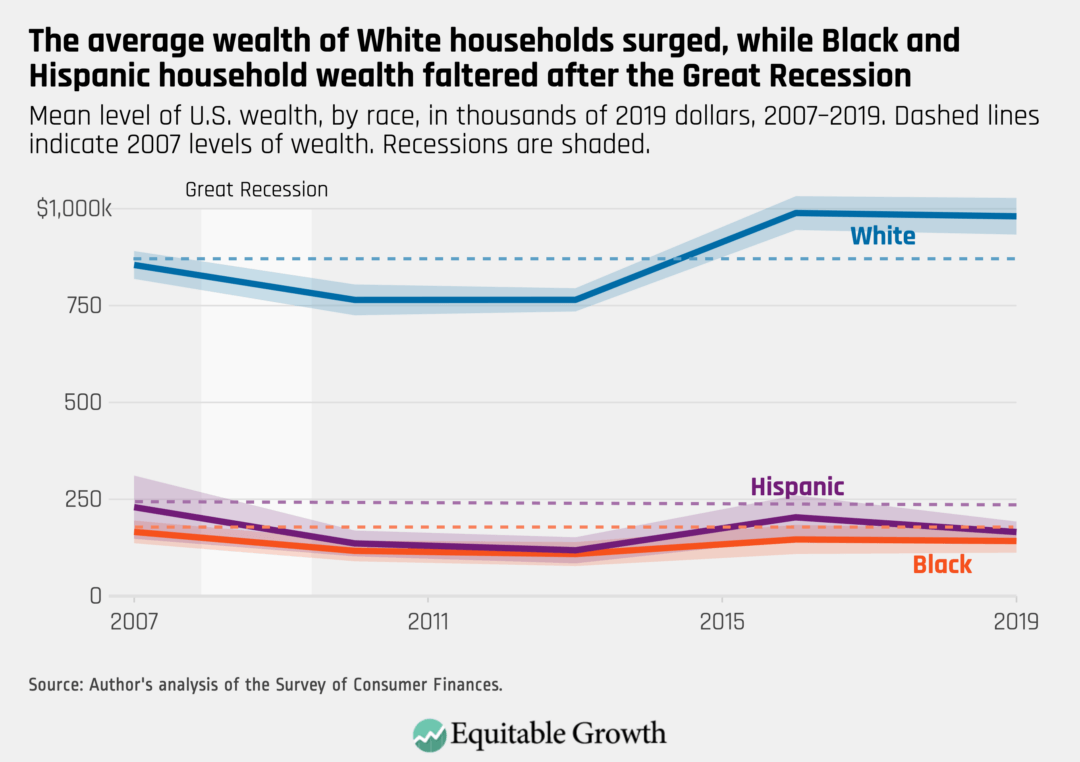

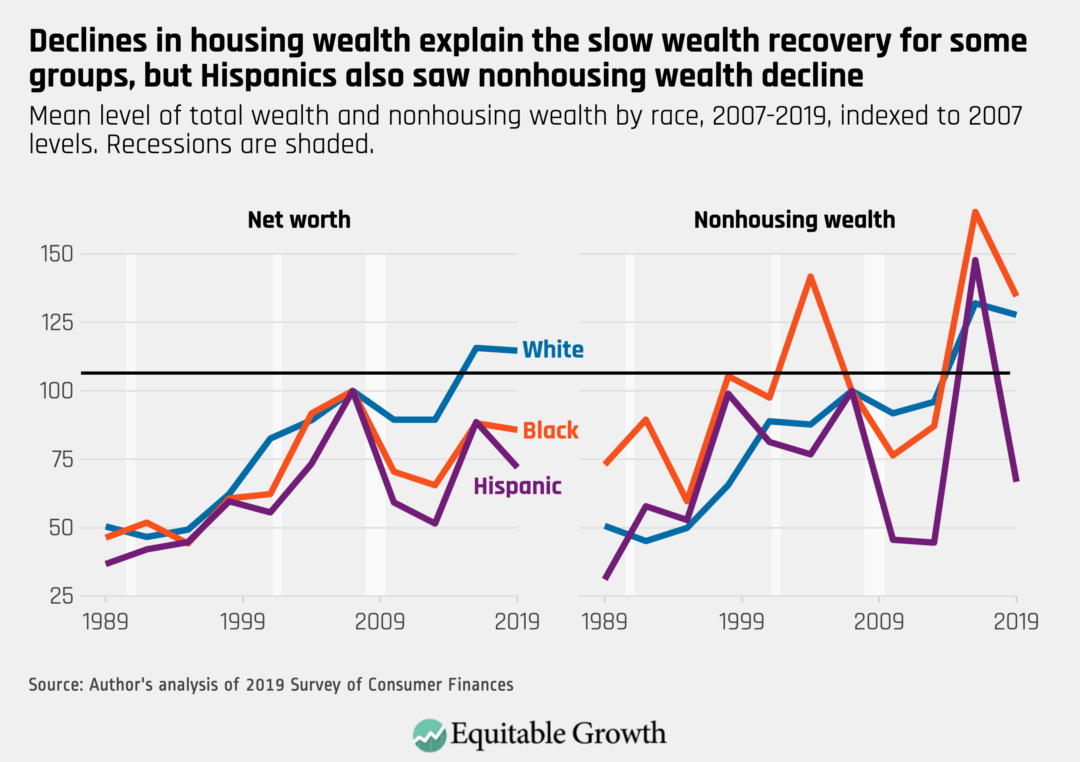

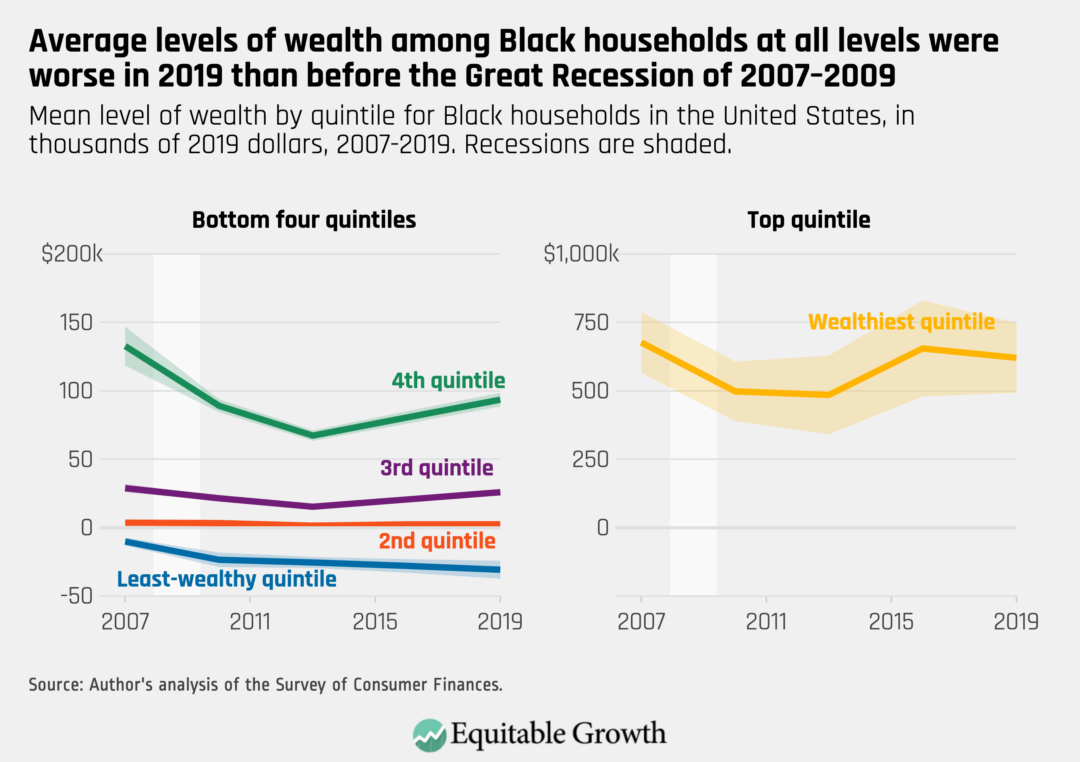

The scary word is not the obstacle, IMO. Socialism gets currency as the more reactionary order crumbles from its own irreconcilable fault lines, and simply cannot continue in the old way. We are seeing that here, and now. People do not go to the immense and expensive trouble to make structural changes to their societies, except under duress. The forces mandating the vast accumulations of wealth in the 70's and afterwards, overwhelmed even the highly skilled, liberal and cautionary efforts of Carter, Clinton, and Obama. The decay of an imperial culture, including its lifelong infections of slavery and its legacy of racism, native genocide, and the moral damage inflicted by imperial wars, has been devastating to our karma. Even in the Left, the damage leaves its imprint in the form of endless anarchisms (under many names) and factional labors. Trump is teaching us that is a luxury with which we will have to part. If not, we may, like German social democrats and communists, have to wait for an alliance of foreign armies to save us.

The Socialist Moment, and How to Extend It

Harold Meyerson reviews (a book and a movie about) Bernie Sanders socialism.While Joe Biden has been making it unmistakably clear that he’s nobody’s socialist tool, the American socialist movement—most of whose adherents will be voting for Biden—has continued to expand. The Democratic Socialists of America (to which I’ve belonged since the Neolithic Age) now has more than 70,000 members and has launched a campaign to raise that number to 100,000. At its current rate of growth, its membership rolls may well surpass that of the Debs-era Socialist Party, which claimed 118,000 dues-payers at its early-20th-century zenith.

The rebirth of American socialism has come complete with any number of explanatory and exhortatory books, the best of which was published late last month: The Socialist Awakening: What’s Different Now About the Left, a brief, incisive volume by veteran political journalist, longtime democratic socialist, and sometime American Prospect contributor John B. Judis. The book is Judis’s third in a series published by Columbia Global Reports. In it, as in its two predecessors The Populist Explosion and The Nationalist Revival, Judis tracks the consequences of the failures of globalized capitalism to sustain working- and middle-class prosperity and stability since the 2008 collapse, and the concomitant rise of both left and right in the wake of those failures. As is not the case in the other two volumes, however, Judis writes not merely as an analyst of an ideology’s return but as an advocate for its necessity, with particularly shrewd assessments of how the new American socialism can advance, and, alternatively, how it may marginalize itself into irrelevance.

More from Harold Meyerson

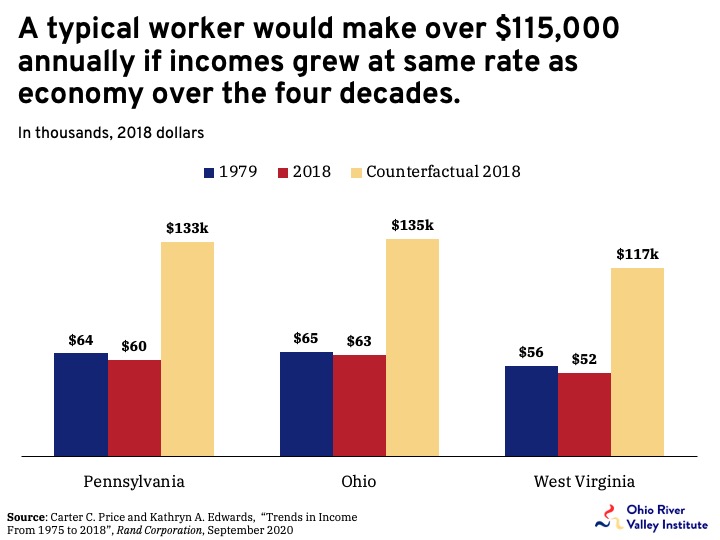

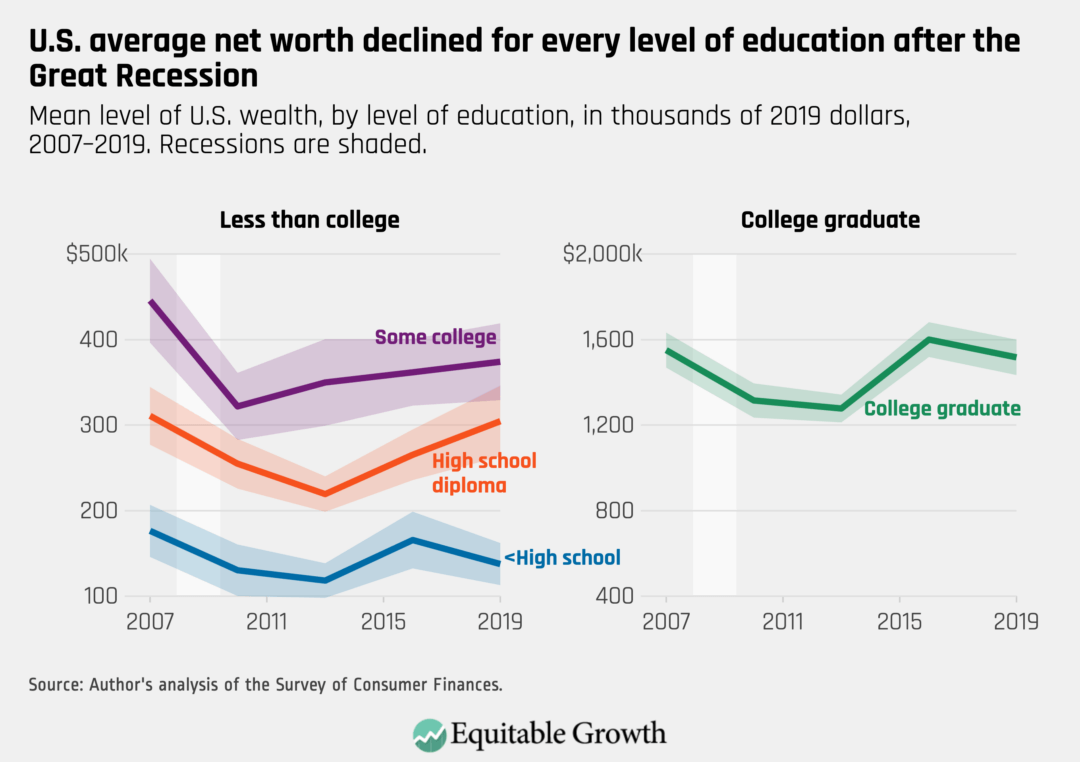

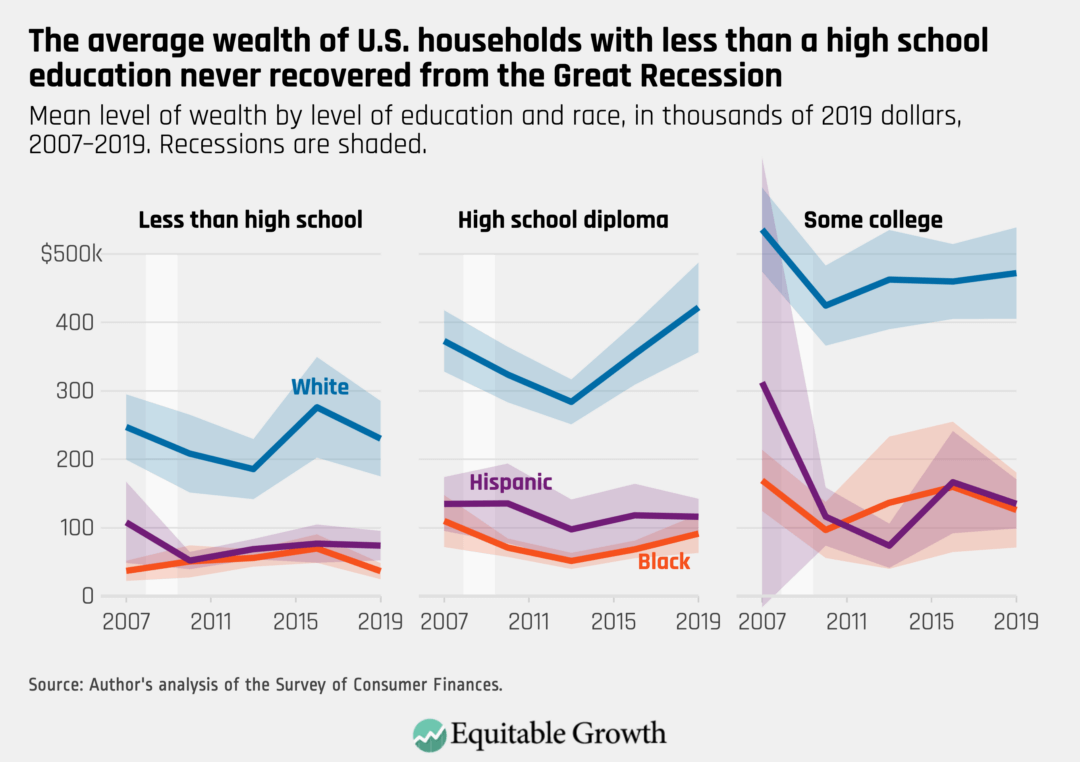

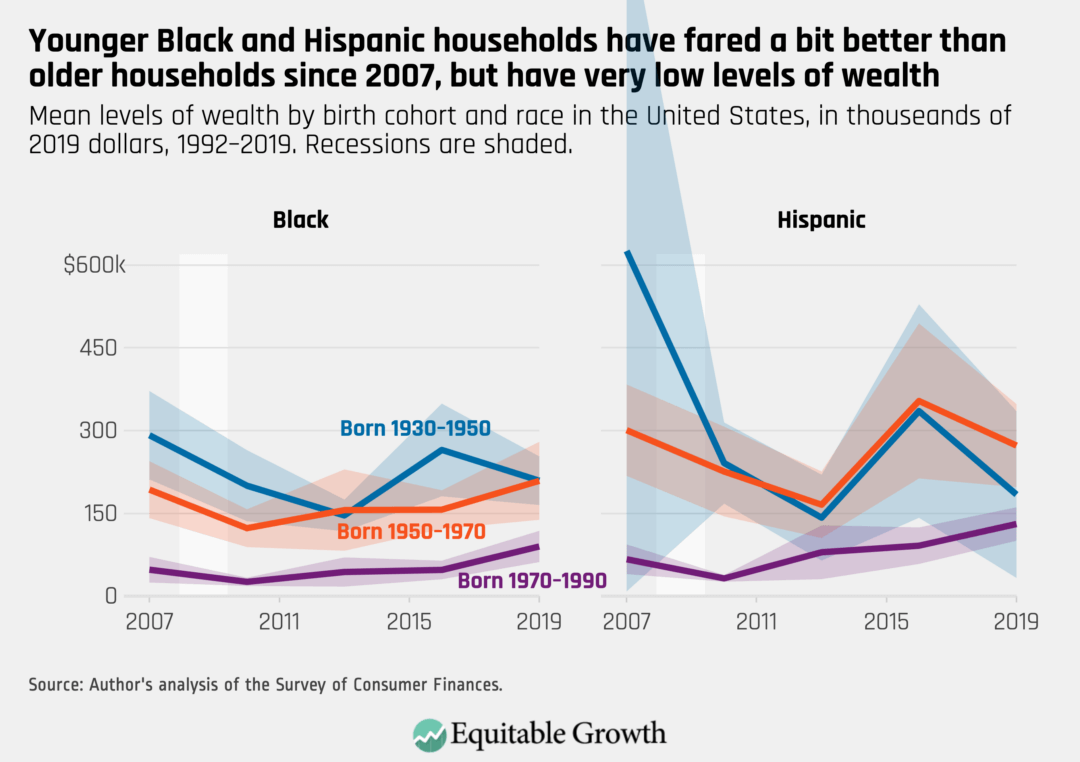

Judis focuses on two periods in American socialism’s long history: the Debs Era of 1900 through 1920, and the Bernie Sanders Surge, which began to incubate with the Occupy movement of 2011 but didn’t really take off until Sanders began running for president in 2015. Both were periods in which capital concentrated wealth and power, in which little of either trickled down to most Americans, in which the New Deal’s semi–social democratic reforms had either not yet been enacted or had been discarded in the post-1970 turn toward laissez-faire.

Sanders has always made it plain that socialist leader Eugene V. Debs was his hero, but in Judis’s telling, the key to Sanders’s zeitgeist-changing success was his move away from the socialist insularity that Debs espoused. While nominally remaining a political independent, Sanders won election to Congress on a social democratic platform of greater regulation of capital, greater power for workers, an expansion of social welfare and economic rights, and a pledge that he’d caucus with the Democrats. When he began running for president in 2015, Sanders made clear his model of socialism was the Scandinavian mixed economy. But as Judis recounts, after Columbia University historian Eric Foner sent him an open letter that emphasized a more American pedigree for socialist initiatives, Sanders took the hint. As I recounted in the Prospect, in Sanders’s two speeches that he billed as his definition of socialism—one given at Georgetown University in 2015, the second at George Washington University in 2019—he cited Franklin Roosevelt and Martin Luther King as his forebears in the struggle for socialist reforms.

In keeping with that expansive definition, Judis emphasizes the broad socialist “network” that’s emerged today, which extends well beyond DSA card-carriers. It includes a range of progressive think tanks (like the Economic Policy Institute and the Roosevelt Institute) and magazines; most importantly, it includes not just the avowed socialists in elected office but a host of progressives whose politics are indistinguishable from the socialists’ politics, as Elizabeth Warren’s were from Sanders’s.

Expanding that network, as socialists like union leaders Sidney Hillman, A. Philip Randolph, and Walter Reuther did during the New Deal and the postwar period, will be as important, if not more important, to the social democratization of today’s United States than the growth of DSA per se, Judis contends. What could retard that growth, he continues, would be continuing the hold that a relatively small group of orthodox Trotskyists now have over DSA’s leadership. The majority of DSA members, he argues, are Berniecrats, happy to work for socialist and other progressive candidates seeking office as Democrats. (I believe he’s right about this.) They understand, as Sanders does and as DSA founder Michael Harrington did, that third-party politics are a dead end in the current configuration of the American electoral system, and that socialists have won power in democracies only when allied with other progressives on behalf of social democratic programs. Such an approach is anathema to the neo-Trotskyist cadres in DSA, for whom a kind of socialist identity politics eclipses both class politics and that of a 21st-century popular front.

Judis also makes the case for a socialist version of nationalism, at which many in today’s socialist movement will look askance. So long as democratic nations offer the one kind of government where majority rule holds sway, though, I think Judis has a point. While capitalism has had no trouble going global (in part to escape the regulations enacted by democratic nations), socialism cannot yet call on any planetary democratic body to reform the global economy. Moreover, people’s support for welfare states funded with their taxes, Judis points out, seldom extends beyond their nation’s borders. To advance a slightly different viewpoint, it’s worth noting that the nation that has given the highest share of its GDP in foreign aid—sometimes to insurgent movements, like the African National Congress—was Sweden under the Social Democrats. Of course, that was when Sweden also had the world’s most expansive welfare state for its own citizens.

Judis writes not merely as an analyst of an ideology’s return but as an advocate for its necessity.

As events would have it, the publication of Judis’s book coincides with the premiere of a film that seeks to introduce and normalize socialism to American viewers. Indeed, The Big Scary ‘S’ Word, a film by documentarian Yael Bridge, will have its first festival screening later today.

In Judis’s terminology, The Big Scary ‘S’ Word is a film about the broad socialist network, and broad left history, rather than a look at, say, the American Socialist and Communist Parties, or at DSA today. The focus is on progressives in motion, then and now, and their connection, explicit or implicit, to socialists and socialism, as distinct from the substance of their involvement in the socialist movement as such. Rather than disentangle the socialist and nonsocialist threads that came together to make the civil rights movement, for instance, the picture simply documents the socialism of Martin Luther King. Some of the environmental protests it shows may not have been populated by socialists, but they’re juxtaposed with interviews with Naomi Klein in which she connects a socialist perspective to any serious effort to save the planet. There’s a marvelous segment, replete with old films and photos, on the socialists’ 40-year control of Milwaukee’s city government, but no discussion of the social democratic meliorism of Victor Berger, the Milwaukee socialist leader and a contemporary of Debs who did not share Debs’s antipathy to reformist socialism. For that, you need to consult Judis’s book, which is pitched at a narrower audience than Bridge’s film.