https://equitablegrowth.org/executive-action-to-combat-wage-theft-against-u-s-workers/

Overview

Wage theft against U.S. workers exacerbates the long-run problem of low and stagnant wages. When companies commit wage theft, they impoverish families and deprive workers of the just compensation for their hard work, robbing workers of the value they contribute to economic growth and exacerbating economic inequality.

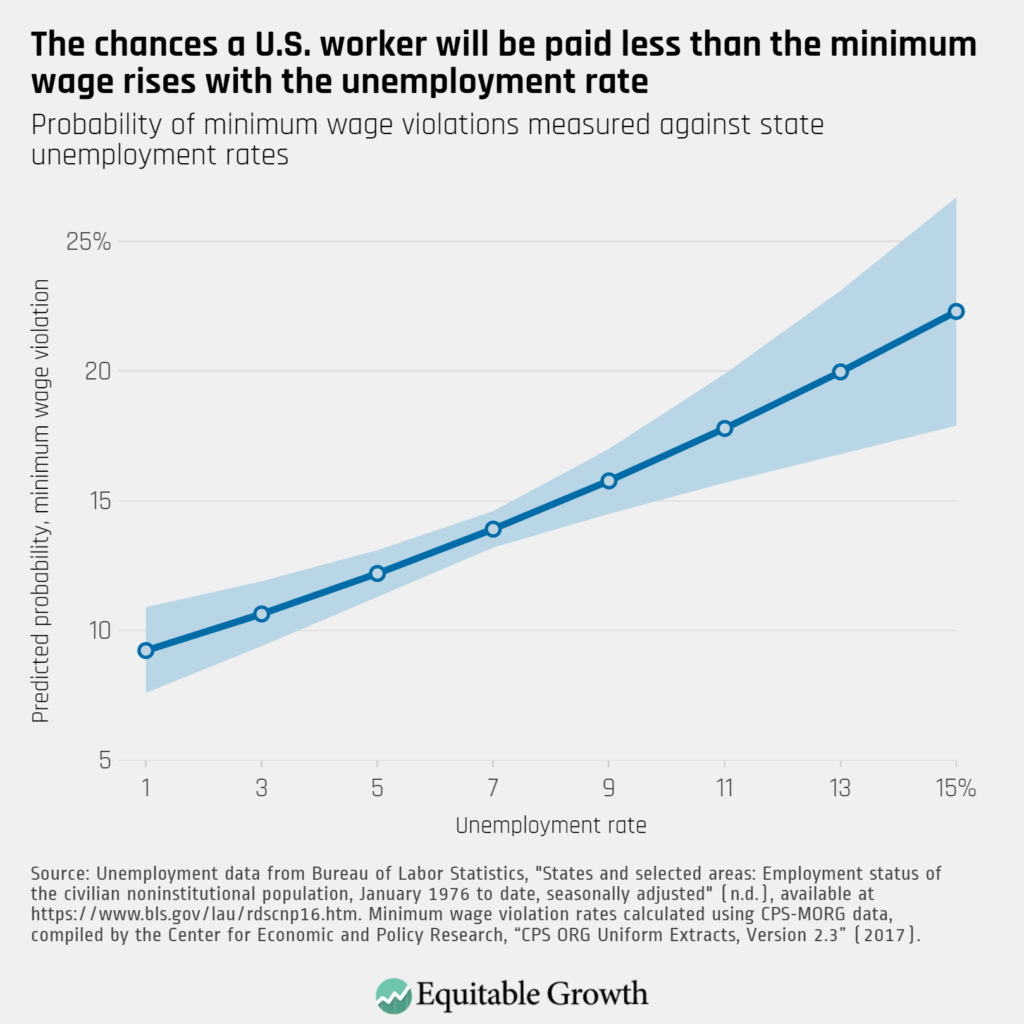

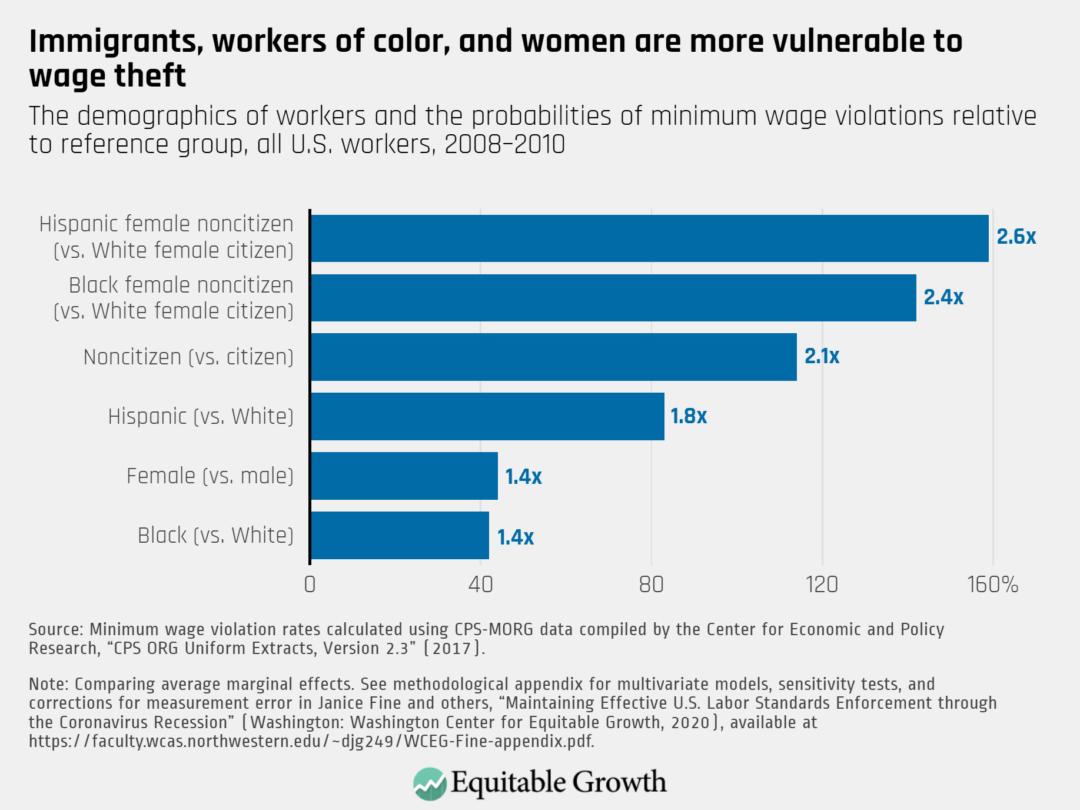

The odds that a low-wage worker will be illegally paid less than the minimum wage ranges from 10 percent to 22 percent, depending on overall economic conditions, and each violation costs that worker an average of 20 percent of the pay they deserve. Women, people of color, and noncitizens are especially vulnerable to wage theft and especially likely to feel they are not in a position to report the crime and get justice.

Cracking down on lawbreaking companies that don't pay workers what they are owed is a straightforward way for the Biden administration to raise the incomes and living standards of U.S. workers and their families.

Executive action

The Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor is the principal agency tasked with detecting, deterring, and punishing wage theft under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The Biden administration can take several steps to enhance the power and effectiveness of this important agency:

- Ask for a large increase for the budget of the Wage and Hour Division in the president's fiscal year 2022 budget request

- Prioritize strategic enforcement to use resources as effectively as possible

- Pursue co-enforcement with community-based organizations

- Protect workers from misclassification as independent contractors

We will discuss each in order below.

INCREASE THE BUDGET AND INSTITUTIONAL CAPACITY OF THE WAGE AND HOUR DIVISION

One of the central problems facing U.S. workers is that the Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor does not have the resources necessary to fulfill its responsibilities. As of May 1, 2020, the division employed 779 investigators to protect more than 143 million workers, which is fewer than the 1,000 investigators it employed back in 1948 when it was only responsible for safeguarding the rights of 22.6 million workers.

President Joe Biden's first budget should request that Congress more appropriately fund the Wage and Hour Division. For instance, the International Labor Organization recommends a benchmark of one investigator per 10,000 workers, which would require roughly 13,500 more investigators to be hired. Currently, this may be out of reach. But, at the very least, the Biden administration's first budget request for the division should, in real terms, exceed the FY2016 request for $332,543,000 to fund 2,044 full-time staff.

The Wage and Hour Division can also work better with state and local agencies. A grant program should be created to support state and local enforcement agencies to facilitate sharing of innovative strategies and practices. Such a program would promote more effective enforcement at all levels while enhancing the potential for coordinating across agencies. In addition, the division should review and update its Memoranda of Understanding with state enforcement agencies that allow for reciprocal information-sharing and maximize coordinated interagency enforcement efforts.

PRIORITIZE STRATEGIC ENFORCEMENT

No matter what the funding situation is, the Wage and Hour Division can also more effectively use its resources to police illegal conduct by businesses. Strategic enforcement differs from reactive, complaint-based enforcement in that agencies proactively and visibly target high-violation industries and maximize the use of enforcement powers to increase the real and perceived costs of noncompliance with labor laws, without waiting for vulnerable workers to initiate complaints.

The division should reprioritize its personnel and other resources toward pursuing proactive investigations to better reach those industries with high violation rates but in which few complaints are filed. Under the Obama administration, roughly half of all investigations were initiated proactively. This is especially important today, amid the coronavirus recession. Research demonstrates that wage violations increase when the unemployment rate is high. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Even though U.S. workers are more likely to experience wage violations during moments of economic contraction, that does not mean they are more likely to initiate complaints. The scarcity of jobs means that workers may not be able to find alternatives to their current employment situation, making them more afraid to complain about wage theft, lest they be fired or retaliated against. The power differential between workers and employers in economic downturns simultaneously emboldens employers who treat workers poorly and raises the stakes for workers who complain. This problem is most acute among low-wage workers who face the largest power differential vis-à-vis their employers.

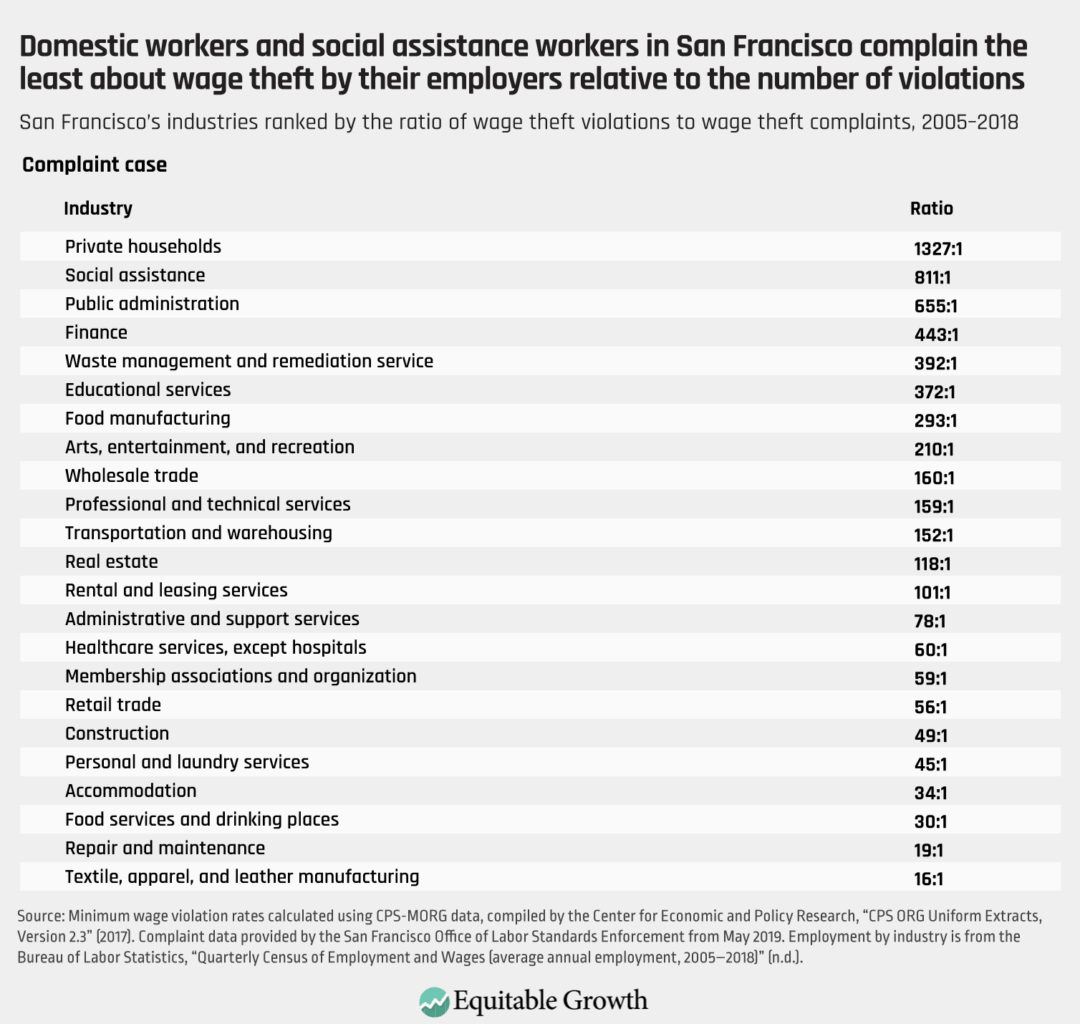

Research on minimum wage enforcement suggests that workers in industries with the worst conditions are much less likely to complain about wage theft. Most wage theft goes unreported, and it is especially present in industries where women and people of color are overrepresented. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The Wage and Hour Division needs to prioritize strategic enforcement, so its limited budget has the maximum impact on the most-vulnerable workers and most wage-theft-prone sectors. It can do this in several ways, according to the authors of the essay "Strategic enforcement and co-enforcement of U.S. labor standards are needed to protect workers through the coronavirus recession" in Equitable Growth's new book of essays, Boosting Wages for U.S. Workers in the New Economy:

- "First, the use of proactive investigations in targeted industries means enforcement resources are more likely to identify and reach vulnerable workers who are unlikely to complain."

- "Likewise, industry research to identify industry structure, influential employers, and widespread noncompliant industry practices helps agencies target employers that are likely to get the attention of others in the industry."

- "Strategic enforcement includes … assessing high damages and penalties in addition to back wages owed." These measures deter future violations by changing the cost-benefit calculation some employers make when they decide that violating the law is worth the risk of being caught.

By not only increasing the budgets of enforcers, but also by using those limited resources more strategically, the U.S. Department of Labor can ensure that its investments in enforcement have maximum impact.

PURSUE CO-ENFORCEMENT WITH COMMUNITY-BASED ORGANIZATIONS

One of the central problems with complaint-based investigations is that some classes of workers are less likely to report wage theft than others. Power dynamics at workplaces and in the community mean that women, noncitizens, and people of color risk more when they report abuses. Indeed, this is the pattern that the data show. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

In a co-enforcement model, labor agencies enter formal partnerships with civil society organizations that have strong relationships with low-wage workers and deep knowledge of high-violation sectors to help uncover violations that would otherwise go unreported and provide support to vulnerable workers so that they face lower levels of risk when they speak up. As explained by the same labor market scholars cited above:

Problems will remain hidden unless workers speak up, yet vulnerable workers will not speak up in isolation …Without a connection to the workforce on which the agency can build an investigation, proactive investigations can be daunting and the agency may be unable to establish violations are occurring. Worker organizations have access to information on labor standards compliance that would be difficult, if not impossible, for state officials to gather on their own.

To that end, the Wage and Hour Division should engage in thoughtful outreach to worker organizations. To do so, the division should hire at least one community outreach and resource planning specialist for each of its 54 district offices. These CORPS workers are full-time Wage and Hour Division staff charged with working with worker centers, unions, and community organizations on campaigns related to the division's targeted industries before and after investigations. These officers should also, when possible, facilitate partnerships on enforcement actions, which they have not prioritized in the past.

PROTECT WORKERS FROM MISCLASSIFICATION AS INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS

Wage theft is much easier to monitor and prosecute when employment relations are well-defined and an employer's responsibility to its workers is clear. Lax rules under the Fair Labor Standards Act about whether workers should be classified as an employee or as an independent contractor naturally advantage employers, who are more able to litigate these legal grey areas. Classifying workers as independent contractors is a common way for companies to evade their legal responsibilities and oversight by the Wage and Hour Division.

Misclassifying workers as independent contractors, rather than as employees, allows employers to disregard most safety net protections the United States has established for workers, including wage laws, but also health and safety regulations, protection from discrimination, and the right to organize in a union. The research clearly establishes that the independent contractor classification further reduces low-wage workers' total earnings. Misclassification can economically disadvantage workers by:

- Outright lowering their pay below the minimum wage or overtime threshold (often by forcing them into complex and ever-changing pay schemes)

- Forcing contractors to perform work tasks while not being paid

- Forcing workers to purchase, use, and maintain personal resources or equipment (their own cars, for instance) to accomplish their job

Though wage theft from contractors usually operates through these more elaborate and ostensibly legal channels, worker misclassification also breeds outright wage theft, as a recent case by the Federal Trade Commission against Amazon.com Inc. shows.

The Wage and Hour Division should clarify who is an employee under the Fair Labor Standards Act and who is an independent contractor. To do so, it should follow the lead of states such as Massachusetts and California, and adopt a simple test called the "ABC test" to determine employment status. Typically, the ABC test has three factors, all of which the alleged employer must demonstrate in order for the worker to be an independent contractor:

- The worker is free, under contract and in fact, from control or direction by the company.

- The service provided is outside the alleged employer's usual course of business.

- The worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, profession, or business.

A rebuttable presumption of employee status and the ABC test should replace the economic realities test under the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Late in the Trump administration, the Wage and Hour Division released an independent contractor rule that made it easier for employers to misclassify their workers as contractors, lowering their pay in direct opposition to the goals of the Fair Labor Standards Act. Thankfully, this rule has now been delayed by the new leadership of the Wage and Hour Division. The division should go further and revoke or revise the proposed rule, and establish a new independent contractor rule that protects workers along the lines of the ABC test, fulfilling the intent of the Fair Labor Standards Act to correct "labor conditions detrimental to the … general well-being of workers."

Experts to consult

- Kate Bahn, director of labor market policy, Washington Center for Equitable Growth

- Janice Fine, professor of labor studies and employment relations, Rutgers University, and director of research and strategy, Center for Innovation in Worker Organization

- Alix Gould-Werth, director of family economic security policy, Washington Center for Equitable Growth

- Corey Husak, senior manager, government and external relations, Washington Center for Equitable Growth

- Jenn Round, senior fellow, Center for Innovation in Worker Organization, Rutgers University

- David Weil, dean and professor, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University

RELATED

-- via my feedly newsfeed

No comments:

Post a Comment