An amusing combo, but he is provocative. This is a good post.

https://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2020/03/on-capitalist-stagnation.html

One of the problems with even the best journalism is that it reports day-to-day events without putting them into context, thereby telling us about the weather but not the climate. So it is with the news that ten-year Treasury yields have hit a record low.

Although the latest move is due to increased risk aversion triggered by the coronavirus this merely continues a long-term trend. Nominal yieldshave been trending down since the 80s, and real yields probably since it 90s.

Why? Standard explanations talk of the shortage of safe assets and global savings glut. Useful as they are, such explanations miss something important. This is that basic theory (and common sense) tells us that there should be a link between yields on financial assets and those on real ones, so low yields on bonds should be a sign of low yields on physical capital.

And they are. My chart shows that the profit rate for US non-financial companies has trended down since the 1950s. I'm not using fancy Marxian calculations here – though they tell a similar story. I'm simply using the Fed's own numbers, expressing pre-tax profits as a percentage of non-financial assets measured at historic cost. Although this profit rate is higher than it was in the crises of 2000-01 and 2008-09, it is much lower now than it was in the 60s and 70s. And profits have never sustainably recovered from the crisis of the 70s and 80s. Even by their own lights, therefore, neoliberal policies – such as lower taxes, sharper CEO incentives, weak unions and a focus on shareholder value - have failed.

You might find this surprising. How can we reconcile it with the fact that, until a few days ago, the stock market was at a record high? Simple. For one thing, listed firms are an unrepresentative sample of all firms. They tend to be bigger and more monopolistic than the average – and the bigger ones among them are more profitable. And for another, the market's high valuations reflect the hope that firms which are not very profitable (or loss-making such as Tesla) today will deliver monopoly profits in future. If we look past a few giant monopolies, the typical American firm has been struggling.

In light of this, three Big Facts make sense.

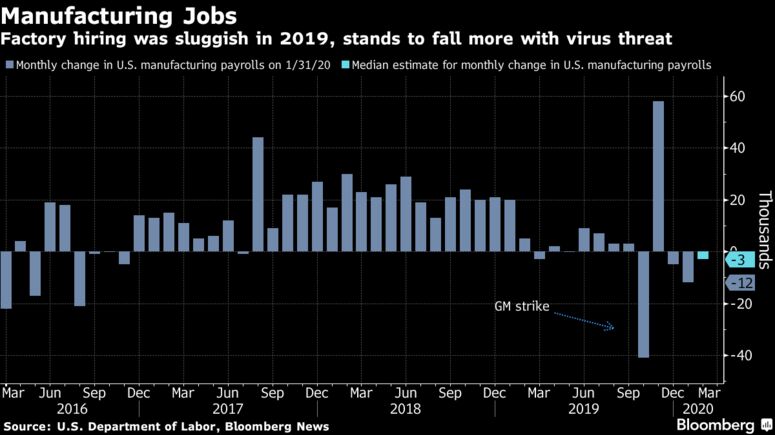

The first is the slowdown in productivity growth. Having risen by 2.2% per year in the 50 years to 2007, output per worker-hour has grown only one per cent per year in the last ten years. One reason for this (of several) is that lower profits reduce the incentive to invest and innovate. This is especially the case when low profits for many firms co-exist alongside monopoly power for a few, because monopolies prefer to entrench their power rather than innovate. Secular stagnation did not drop from the sky. It's the product of trends within capitalism.

The second is capitalism's vulnerability to crisis. To see this, imagine a different world in which there were abundant big profit opportunities for non-financial firms in the early 00s. The flow of savings from Asia would then have financed these cheaply. We'd thus have seen strong growth in the real capital stock and in productivity and profits (and maybe wages and employment too). But we didn't, because there were few such opportunities. Savings flowed instead into housing and mortgage derivatives thereby stoking up a bubble which led to the crisis.

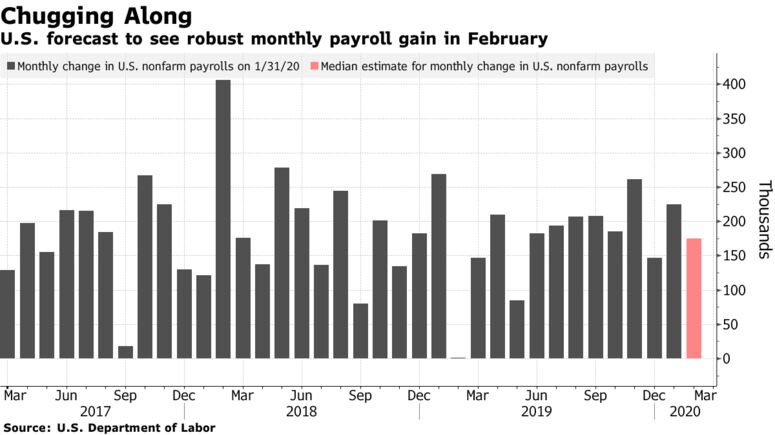

The third fact is documented by Anne Case and Angus Deaton in their new book, Deaths of Despair, wherein they show that, for middle-aged white people without much education, deaths from suicide, alcohol and drug misuse have soared since the 90s. A big reason for this is that employment opportunities for such people have worsened; even in today's supposedly "tight" labour market, people without degrees are much less likely to be in work than they were in the 90s. And many of those who are in work are in worse jobs. Case and Deaton note that white men without a degree earn less in real terms than they did in 1979. Fewer and worse jobs mean a lower sense of self-worth, stress, family breakdown and hence deaths of despair.

But why have such job opportunities declined? It's easy to blame globalization or technical change. But these are different ways of saying that it is no longer profitable for capitalism to employ less-skilled people at a decent wage.

The drop in bond yields is therefore one of the more innocuous symptoms of a dysfunctional capitalism.

Of course, all these trends have long been discussed by Marxists: a falling rate of profit (pdf); monopoly leading to stagnation; proneness to crisis; and worse living conditions for many people. And there is plenty of evidence (pdf) for them. The problem is, however, that many people want to shut their eyes to this evidence. In this sense, perhaps today's two big stories – the record-low for bond yields and the success of Joe Biden in the Super Tuesday primaries – are related.

-- via my feedly newsfeed