http://understandingsociety.blogspot.com/2020/02/methods-of-causal-inquiry.html

INSIGHTS

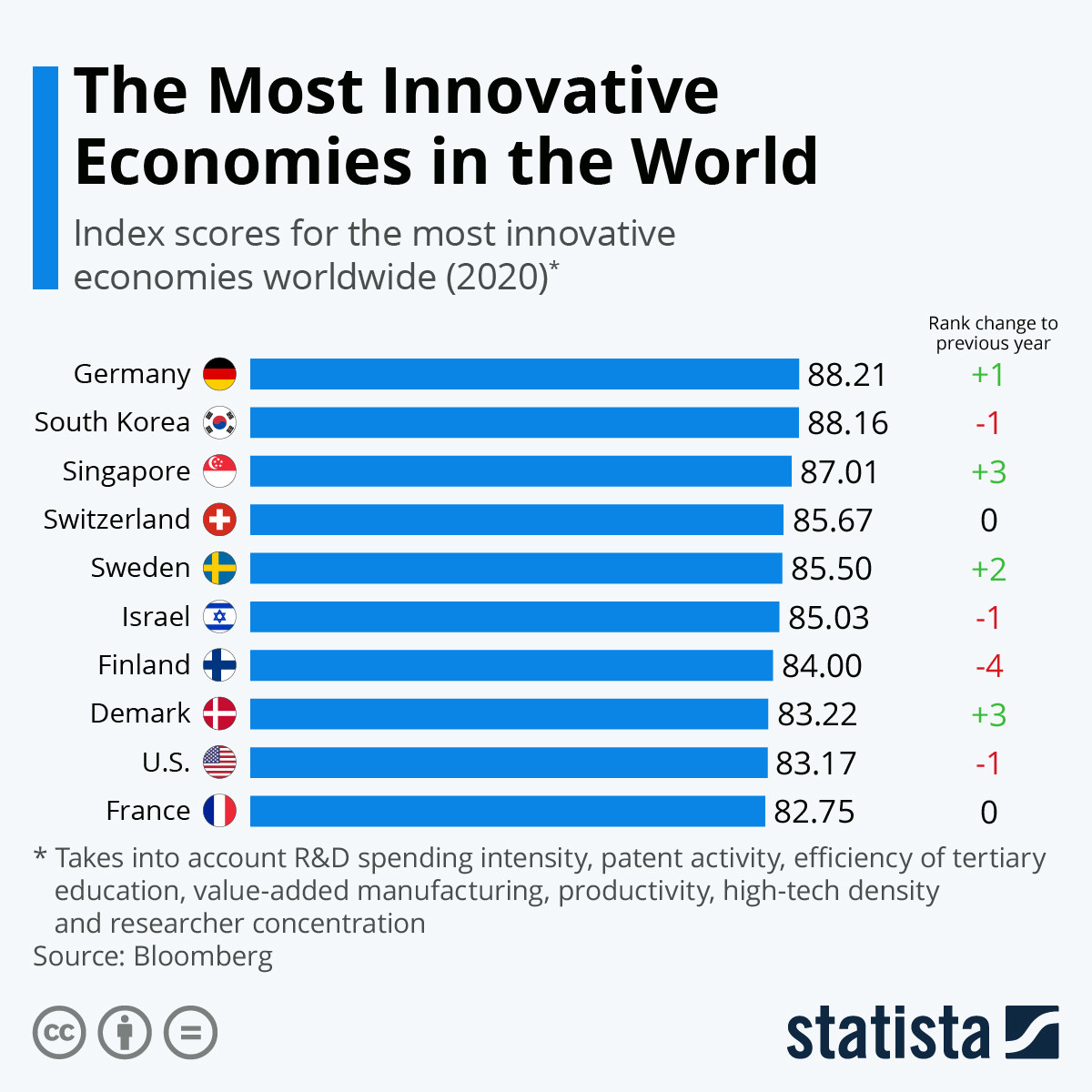

This diagram provides a map of an extensive set of methods of causal inquiry in the social sciences. The goal here is to show that the many approaches that social scientists have taken to discovering causal relationships have an underlying order, and they can be related to a small number of ontological ideas about social causation. (Here is a higher resolution version of the image; link.)

We begin with the idea that causation involves the production of an outcome by a prior set of conditions mediated by a mechanism. The task of causal inquiry is to discover the events, conditions, and processes that combine to bring about the outcome of interest. Given that causal relationships are often unobservable and complexly intertwined with multiple other causal processes, we need to have methods of inquiry to allow us to use observable evidence and hypothetical theories about causal mechanisms to discover valid causal relationships.

The upper left node of the diagram reviews the basic elements of the ontology of social causation. It gives priority to the idea of causal realism -- the view that social causes are real and inhere in a substrateof social action constituted by social actors and their relations and interactions. This substrate supports the existence of causal mechanisms (and powers) through which causal relations unfold. It is noted that causes are often manifest in a set of necessary and/or sufficient conditions: if X had not occurred, Y would not have occurred. Causes support (and are supported by) counterfactual statements -- our reasoning about what would have occurred in somewhat different circumstances. The important qualification to the simple idea of exceptionless causation is the fact that much causation is probabilisticrather than exceptionless: the cause increases (or decreases) the likelihood of occurrence of its effect. Both exceptionless causation and probabilistic causation supports the basic Humean idea that causal relations are often manifest in observable regularities.

These features of real causal relations give rise to a handful of different methods of inquiry.

First, there is a family of methods of causal inquiry that involve search for underlying causal mechanisms. These include process tracing, individual case studies, paired comparisons, comparative historical sociology, and the application of theories of the middle range.

Second, the ontology of generative causal mechanisms suggests the possibility of simulations as a way of probing the probable workings of a hypothetical mechanism. Agent-based models and computational simulations more generally are formal attempts to identify the dynamics of the mechanisms postulated to bring about specific social outcomes.

Third, the fact that causes produce their effects supports the use of experimental methods. Both exceptionless causation and probabilistic causation supports experimentation; the researcher attempts to discern causation by creating a pair of experimental settings differing only in the presence or absence of the "treatment" (hypothetical causal agent), and observing the outcome.

Fourth, the fact that exceptionless causation produces a set of relationships among events that illustrate the logic of necessary and sufficient conditions permits a family of methods inspired by JS Mills' methods of similarity and difference. If we can identify all potentially relevant causal factors for the occurrence of an outcome and if we can discover a real case illustrating every combination of presence and absence of those factors and the outcome of interest, then we can use truth-functional logic to infer the necessary and/or sufficient conditions that produce the outcome. These results constitute JL Mackie's INUS conditions for the causal system under study (insufficient but non-redundant parts of a condition which is itself unnecessary but sufficient for the occurrence of the effect). Charles Ragin's Boolean methods and fuzzy-set theories of causal analysis and the method of quantitative comparative analysis conform to the same logical structure.

Probabilistic causation cannot be discovered using these Boolean methods, but it is possible to use statistical and probabilistic methods in application to large datasets to discover facilitating and inhibiting conditions and multifactoral and conjunctural causal relations. Statistical analysis can produce evidence of what Wesley Salmon refers to as "causal relevance" (conditional probabilities that are not equal to background population probabilities). This is expressed as: P(O|A&B&C) <> P(O).

Finally, the fact that causal factors can be relied upon to give rise to some kind of statistical associations between factors and outcomes supports the application of methods of inquiry involving regression, correlation analysis, and structural equation modeling.

It is important to emphasize that none of these methods is privileged over all the others, and none permits a purely inductive or empirical study to arrive at valid claims about causation. Instead, we need to have hypotheses about the mechanisms and powers that underlie the causal relationships we identify, and the features of the causal substrate that give these mechanisms their force. In particular, it is sometimes believed that experimental methods, random controlled trials, or purely statistical analysis of large datasets can establish causation without reference to hypothesis and theory. However, none of these claims stands up to scrutiny. There is no "gold standard" of causal inquiry.

This means that causal inquiry requires a plurality of methods of investigation, and it requires that we arrive at theories and hypotheses about the real underlying causal mechanisms and substrate that give rise to ("generate") the outcomes that we observe.

-- via my feedly newsfeed