Friday, September 18, 2020

Enlighten Radio:Talkin Socialism: All Around the World

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Talkin Socialism: All Around the World

Link: https://www.enlightenradio.org/2020/09/talkin-socialism-all-around-world.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Wednesday, September 16, 2020

Chinese Communist Party Wants Stronger Role in Private Sector [feedly]

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-09-16/chinese-communist-party-wants-stronger-role-in-private-sector

China's Communist Party is looking to strengthen its leadership and control of the country's growing private sector and its employees by extending the work of the United Front further into the business community.

The party called on the United Front to improve the government's leadership role in the nation's private sector, according to guidelines issued by the General Office of the CPC's Central Committee on Tuesday. The front is an umbrella organization that aims to increase the party's influence and control both domestically and internationally.

The move aims to address emerging challenges and risks as the scale of private enterprises increases and private businesspeople have more diverse values and interests. The policy will "strengthen ideological guidance" and "create a core group of private sector leaders who can be relied upon during critical times."

Read more: China Steps Up Communist Party Control in State-Owned Firms

While it's unclear what the new policy will mean for China's millions of private firms, it comes as the state and party are pushing for greater control and influence over more of the economy. That increasingly unclear dividing line between public and private sector is one of the factors behind rising tensions with the U.S. and other states, with ostensibly private firms such as Huawei Technologies Co. seen overseas as tools of Chinese state power.

"The document shows China is trying to mobilize more resources around the national strategy amid the economic slowdown caused by the pandemic and the deterioration of diplomatic and trade relations with the US," said Yue Su, China economist at the Economist Intelligence Unit, based in Shanghai. "The authorities will give priority to companies that assist in realizing policy goals when allocating financial and policy resources," she said.

Private businesses account for 60% of China's economic output and create 80% of urban jobs, but their position has been difficult in recent years, with the perception that the government under President Xi Jinping favored the state sector. In addition, they have borne the brunt of the U.S.-China trade war as many are export-oriented manufacturers. The Covid-19 outbreak and economic slump have added to their woes this year.

Read more: China's Talk of 'Two Unwaverings' Reveals Private Sector Fears

Notable Details

- This change is in response to profound flux in international and domestic situations

- The CPC will support and serve private businesses to help drive their high-quality growth

- The work of the United Front should cover all private businesspeople including investors, managers, stakeholders, and people from Hong Kong and Macau who invest in the mainland

- The United Front will build a database and talent pool of private businesspeople

— With assistance by Lucille Liu, Yinan Zhao, and Kari Soo Lindberg

-- via my feedly newsfeed

State and local governments still desperately need federal fiscal aid to prevent harmful austerity measures [feedly]

https://www.epi.org/blog/state-and-local-governments-still-desperately-need-federal-fiscal-aid-to-prevent-harmful-austerity-measures/

In March and April of this year, the economy lost an unprecedented 22.1 million jobs. From May to August, 10.6 million of these jobs returned. But nobody should take excess comfort in the fast pace of job growth in those months. It was widely expected that the first half of jobs lost due to the COVID-19-driven shutdowns were going to be relatively easy to get back. But even with the jobs gained since April, the economy remains 11.5 million jobs below its pre-pandemic level in February, and the low-hanging fruit have been largely plucked. One of the key factors that will radically slow the pace of job growth in coming months is the looming state and local fiscal crisis. Using data from the recovery from the Great Recession, we simply show how state and local austerity and job loss can be a lagging indicator, putting severe downward pressure on growth even years after the official recession ends. We find:

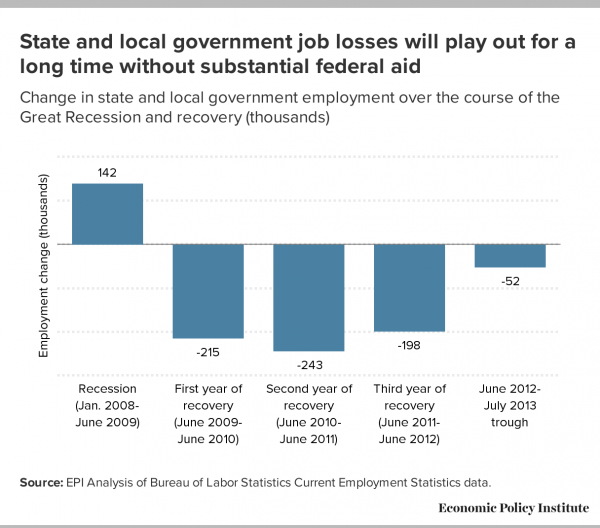

- From the beginning of the Great Recession in January 2008 to the trough of state and local government employment, 566,000 state and local government jobs were lost.

- The state and local employment trough occurred in July 2013, more than five-and-a-half years after the official start of the Great Recession.

- During the official recession from January 2008 to June 2009, state and local governments actually added 142,000 jobs.

- In the first year of recovery (from June 2009 to June 2010), the state and local sector lost 215,000 jobs. The 73,000 jobs lots between December 2007 and June 2010 constituted just 0.3% of state and local employment. Even a year after the recession officially ended, cuts in the state and local sector were greatly softened by the substantial federal fiscal aid included in the American Relief and Recovery Act (ARRA).

- In the second year of recovery (from June 2010 to June 2011), the state and local sector lost 368,000 jobs. Job losses continued through July 2013, with another 250,000 jobs lost.

- State and local governments have already lost jobs during this contraction and are recovering slower than the private sector. Without federal aid now, more jobs—in both the public and private sectors—will be lost down the line.

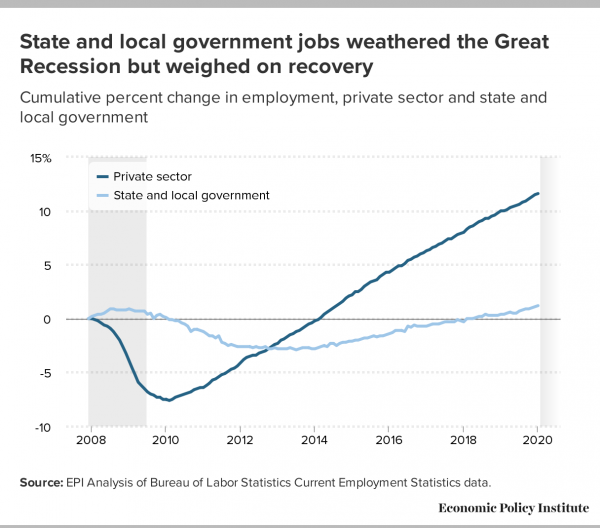

These data are presented below in Figure A. Figure B presents job-losses for state and local and private sector jobs, both indexed to their December 2007 business cycle peak. The upshot of this analysis for today's policymakers is clear: the severe blow to state and local budgets caused by the coronavirus shock is going to drag on growth for years to come absent bold action from federal policymakers. In the case of the Great Recession, the combined effect of job cuts and cuts to other state and local spending delayed a full recovery to pre-Great Recession unemployment rates by more than four years. The lessons could not be clearer: without substantial federal aid to state and local governments, and soon, our near-term economic future will be substantially worse.

Too many policymakers have become far too complacent about the economy's near-term. Between the pulling back of enhanced unemployment insurance (UI) benefits and the near-total inaction on aiding state and local governments' fiscal situation, the next few months will see the economy suffer the effects of having sailed over a pronounced fiscal cliff. So far, the macroeconomic effects of this fiscal cliff have been blunted by the fact that the enormous increase in household savings undertaken during the COVID-19-driven shutdowns has been unwinding. Private, household spending has been the main engine lifting the economy out of the deep well it was in during March and April. It is highly unlikely that this private savings alone can be drawn on enough to neutralize the coming effect of state and local contractions.

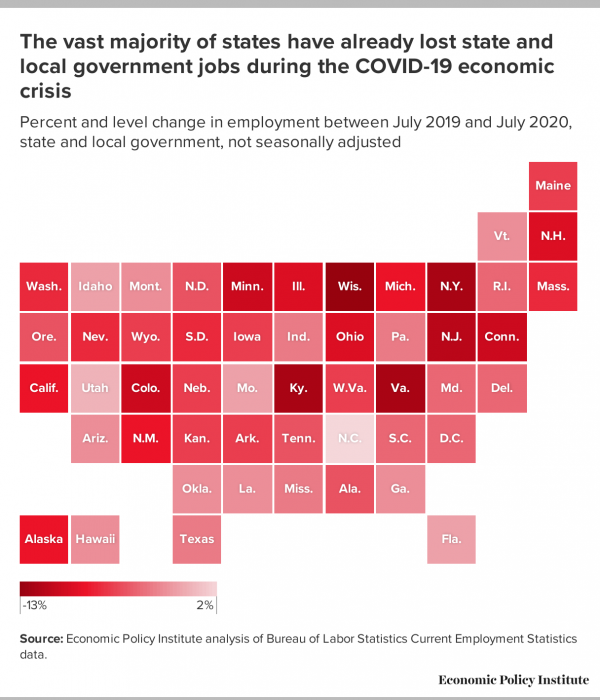

Unlike the Great Recession, state and local government employment has already suffered enormously during the contraction phase of this business cycle, seeing 1.5 million in losses in March, April, and May (some surely related to the sudden shutdown of school systems). But this employment is already lagging private sector growth in the recovery as well. While the private sector has recovered nearly half of the jobs lost in the early months of the pandemic, state and local government jobs have likely only regained about a quarter of their losses. Looking at not-seasonally-adjusted data, employment in these sectors in August 2020 is still 1.1 million below employment in in the same month in 2019. Figure C displays the over-the-year change in state and local government employment as of July—the most recent month available.

These losses cause particular harm to women and Black workers, since they are disproportionately represented in the state and local government workforce. Any impending state and local budget cuts will fall heavily on their shoulders.

Gutting state and local spending during the current recovery would be particularly perverse given how crucial the health and education sectors will be in living with COVID-19 over the next year. School systems will need to spend more, not less, to effectively and safely teach children in the face of hybrid or online learning. Federal dysfunction in getting the virus under control has put huge burdens for doing the right things on virus suppression on state and local governments.

The response to COVID-19 from policymakers has been a repeated series of getting caught behind the curve. Some of this was likely inevitable in dealing with an unforeseen pandemic. But failing to provide state and local aid would be a completely foreseen and unforced blunder, one that will greatly hamper recovery and cause unnecessary suffering.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Saturday, September 12, 2020

States Expect More Damaging Cuts Without More Federal Aid [feedly]

https://www.cbpp.org/blog/states-expect-more-damaging-cuts-without-more-federal-aid

State policymakers will soon begin addressing shortfalls that have already arisen in their current budgets even as they prepare next year's budgets, and many states are bracing to make deeper, more damaging cuts than they've already imposed if they don't receive additional federal fiscal aid.

State and local tax revenues have plummeted as people have less income, shop less, and reduce their economic activity in other ways due to the coronavirus and the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. For example, state sales tax collections in the second quarter of 2020 (April through June) dropped over 14 percent compared to the same quarter a year ago; in a typical year, they'd grow 3 to 5 percent.

Six states (Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Vermont) have delayed adopting a full budget for fiscal year 2021 (which started on July 1 in most states), and the fiscal year hasn't started in Alabama, Michigan, and the District of Columbia. But many states that have adopted their budgets assumed much higher revenues than they now expect and didn't fully account for recent cost increases due to the pandemic. These and other states will undoubtedly revisit their budgets as COVID-19's budgetary toll and the likelihood of more federal aid become clearer. For example:

- California's just-adopted budget includes $11 billion in spending cuts and payment delays that will take effect unless the state receives substantial new federal fiscal aid.

- Colorado, which closed a $3 billion shortfall in its current budget through spending cuts and other measures, faces more cuts next year. "For those of you who haven't heard the news flash, next year is going to be worse," said Rep. Daneya Esgar, chair of the Joint Budget Committee (JBC). "We just did a lot of one-time budget tricks that we did just because we had to — and those will not be at our disposal next year," said Senator Rachel Zenzinger, a JBC member.

- Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont called on agencies to identify at least 10 percent in cuts in the next biennial budget.

- Florida Governor Ron DeSantis recently asked agencies to identify at least 8.5 percent in further cuts in the current budget, beyond the $1 billion DeSantis already cut by veto.

- Hawai'i Governor David Ige said, "I'm just concerned that [federal policymakers] are not going to provide additional funds," warning that the state will have to impose pay cuts or furloughs for public workers unless it gets more federal help or more flexibility to use CARES Act funding to close its budget hole. U.S. Senator Brian Schatz noted, "As we try to get through this, both in terms of public health and the economy, there's just no way we can handle the pandemic if state and county governments are forced to do layoffs in the fall."

- Michigan's budget director, Chris Kolb, noted that projected revenues over this fiscal year and next have fallen by $4.2 billion since the coronavirus hit. "These are large revenue losses that will require difficult decisions without additional federal aid, especially in fiscal year 2022," he said. "Tough decisions will still be required in the next five weeks."

- Texas Governor Greg Abbott called on agencies to propose a 5 percent cut from their current two-year budget, which produced harmful proposals such as a $133 million cut in health services related to women's health, family violence prevention, and services for individuals with traumatic brain injuries.

- Wyoming Governor Mark Gordon called on agencies to propose cuts of up to 30 percent from their current budget to offset crashing revenues due to the recession and falling revenue from natural resource extraction. "The cuts we've talked about here are getting close to the bone," he said. "In some cases we really are talking about the bone. We will talk about some very precious programs and some very valuable people. I don't look forward to any of this."

Some states have already made deep cuts to offset huge revenue shortfalls triggered by COVID-19 and the recession. The initial cuts of spring and early summer caused sizable harm through layoffs, furloughs, and cuts to vital public services. States and localities already have laid off or furloughed over a million workers, far more than in the Great Recession of a decade ago and its aftermath. Without a new round of flexible federal aid, the cuts will only grow, harming families, communities, and businesses and delaying the economic recovery.

States will try to shield K-12 public schools and health services, but it's nearly impossible to protect them entirely over time, since education and health make up more than half of state spending nationwide. Indeed, several states have already slashed crucial health programs, such as substance use treatment and prevention.

As the President and Congress negotiate a new relief package, the House-approved Heroes Act offers a sound starting point. It includes close to $900 billon in grants to states, localities, territories, and tribal governments and would boost the share of Medicaid costs that the federal government pays. More fiscal aid is essential for communities nationwide, especially those hit hardest by the unprecedented events of recent months.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Medicaid Enrollment Continues to Rise [feedly]

https://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaid-enrollment-continues-to-rise

Medicaid enrollment rose 8.4 percent from February to July as millions of Americans lost their jobs or experienced sharp income losses due to the COVID-19 recession. That's in the 30 states for which we have data, which if we extrapolate nationwide would mean about 6 million more people enrolled in Medicaid — and likely more, given continued increases in August in states with available data. The growing need for Medicaid coincides with a large and growing state budget crisis, which has already prompted some states to cut Medicaid and will likely prompt more to do so unless the federal government provides more aid to states.

Before the pandemic and recession, Medicaid enrollment was flat or falling in most states. It has risen steadily since then, as the figure below shows.

These data include groups for whom enrollment is generally not responsive to economic conditions, such as elderly people and people with disabilities who are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid. Enrollment increases among adults covered through the Affordable Care Act's Medicaid expansion have been much larger — 12.7 percent through July in the 17 states with expansion enrollment data — with Medicaid providing a safety net as millions of adults have lost jobs or income.

These Medicaid enrollment figures are based on preliminary estimates from state websites, as of September 8. Complete enrollment figures for all states from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) are available only through April, but the state-reported data to which we have access largely match the CMS data for the months where both are available.

We included further details and sources in an earlier analysis, which this blog post updates. These are the states for which we now have data, and through which month:

- August: Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Virginia, and West Virginia;

- July: Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Washington, and Wisconsin;

- June: Massachusetts, Montana, Ohio, Texas, and Utah;

- May: Michigan.

Other data confirm that Medicaid enrollment has grown sharply. Second-quarter financial statements from the major health insurance companies serving Medicaid enrollees — Aetna, Anthem, Centene, Molina, and UnitedHealthcare — all show a significant rise in Medicaid enrollment. And most of these companies note that they anticipate further Medicaid enrollment growth as the full impact of job losses takes hold.

Medicaid enrollment increases typically lag increases in people receiving unemployment insurance or SNAP (food stamp) benefits, because people losing jobs or income often focus on their most urgent needs (like food and rent) first, and because people don't always lose job-based coverage immediately upon losing a job. During the current crisis, Medicaid enrollment may lag even further, because COVID-19 has persuaded people to defer non-urgent medical visits, which are often an impetus to enroll in coverage, especially since providers can help people apply. That means that Medicaid enrollment will likely continue to grow in the months ahead.

These increases are almost certainly mitigating the large spikes in uninsurance rates that would otherwise occur as millions lose job-based coverage or can't afford private plan premiums due to the recession. But enrollment growth is also adding to the pressure on state budgets. As states begin to exhaust their options to defer budget cuts, they will likely make deeper and more widespread cuts to Medicaid and other health programs unless federal policymakers provide more funds and maintain strong protections for Medicaid enrollees.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

UI claims rising as jobs remain scarce: Senate Republicans must stop blocking the restoration of UI benefits [feedly]

https://www.epi.org/blog/ui-claims-rising-as-jobs-remain-scarce-senate-republicans-must-stop-blocking-the-restoration-of-ui-benefits/

Last week, total initial unemployment insurance (UI) claims rose for the fourth straight week, from 1.6 million to 1.7 million. Of last week's 1.7 million, 884,000 applied for regular state UI and 839,000 applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). A reminder: Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) is the federal program for workers who are not eligible for regular unemployment insurance, like gig workers. It provides up to 39 weeks of benefits and expires at the end of this year.

Last week was the 25th week in a row total initial claims were far greater than the worst week of the Great Recession. If you restrict to regular state claims (because we didn't have PUA in the Great Recession), claims are still greater than the 2nd-worst week of the Great Recession. (Remember when looking back farther than two weeks, you must compare not-seasonally-adjusted data, because DOL changed—improved—the way they do seasonal adjustments starting with last week's release, but they unfortunately didn't correct the earlier data.)

Most states provide 26 weeks of regular state benefits. After an individual exhausts those benefits, they can move onto Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC), which is an additional 13 weeks of state UI benefits that is available only to people who were on regular state UI. Given that continuing claims for regular state benefits have been elevated since the third week in March, we should begin to see PEUC spike up dramatically soon (starting around the week ending September 19th—however, because of reporting delays for PEUC, we won't actually get PEUC data from September 19th until October 8th). It is also important to remember that people haven't just lost their jobs. An estimated 12 millionworkers and their family members have lost employer-provided health insurance due to COVID-19.

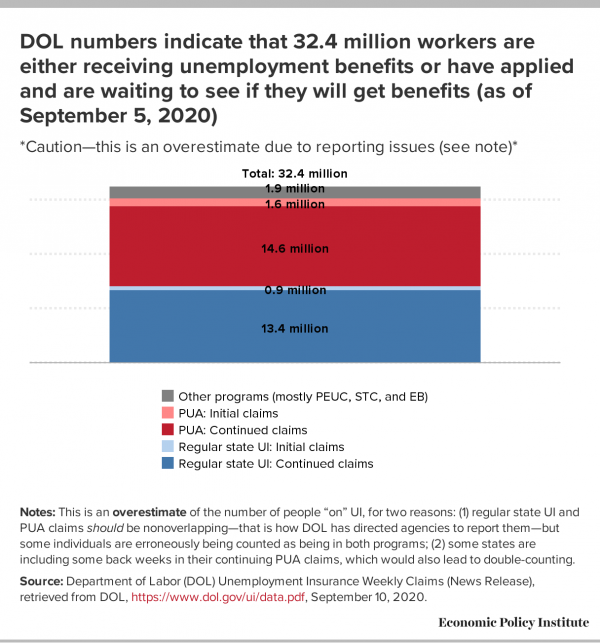

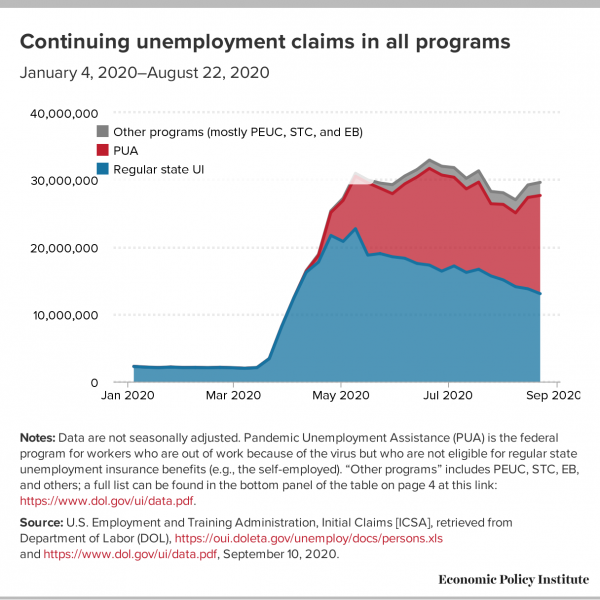

Figure A combines the most recent data on both continuing claims and initial claims to get a measure of the total number of people "on" unemployment benefits as of September 5th. DOL numbers indicate that right now, 32.4 million workers are either on unemployment benefits, have been approved and are waiting for benefits, or have applied recently and are waiting to get approved. But importantly, Figure A is an overestimate of the number of people "on" UI, for two reasons: (1) Some individuals are being counted twice. Regular state UI and PUA claims shouldbe non-overlapping—that is how DOL has directed state agencies to report them—but some individuals are erroneously being counted as being in both programs; (2) Some states are including some back weeks in their continuing PUA claims, which would also lead to double counting (the discussion around Figure 3 in this papercovers this issue well).

Figure B shows continuing claims in all programs over time (the latest data are for August 22). Continuing claims are more than 28 million above where they were a year ago. However, the above caveat about potential double counting applies here too, which means the trends over time should be interpreted with caution.

I have received many questions about how to square the UI numbers with the monthly jobs numbers. This thread from Jobs Day last Friday explains it (in particular, tweets six–eight show how the number of officially unemployed is "undercounted," and tweets 20–24 show how UI claims are overcounted).

Republicans in the Senate allowed the across-the-board $600 increase in weekly UI benefits to expire at the end of July. Last week was the sixth week of unemployment in this pandemic for which recipients did not get the extra $600. That means most people on UI are now are forced to get by on the meager benefits that are in place without the extra payment, benefits which are typically around 40% of their pre-virus earnings. It goes without saying that most folks can't exist on 40% of prior earnings without experiencing a sharp drop in living standards and enormous pain.

In early August, President Trump issued a mockery of an executive memorandum. It was supposed to give recipients an additional $300 or $400 in benefits per week. But in reality, even this drastically reduced benefit will be extremely delayed for most workers, is only available for a few weeks, and is not available at all for many. This chart from The Century Foundation shows how much less in benefits people are getting under Trump's executive memorandum than they did under the CARES Act. The executive memorandum's main impact was to divert attention from the desperate need for the real relief that can only come through legislation. Congress must act, but Republicans in the Senate are blocking progress.

Blocking the $600 is terrible on both humanitarian and economic grounds. The extra $600 was supporting a huge amount of spending by people who now have to make drastic cuts. The spending made possible by the $600 was supporting 5.1 million jobs. Cutting that $600 means cutting those jobs—it means the workers who were providing the goods and services that UI recipients were spending that $600 on lose their jobs. The map in Figure B of this blog post shows many jobs will be lost by state now that the $600 unemployment benefit has been allowed to expire. The labor market is still 11.5 million jobs below where we were before the virus hit. Now is not the time to cut benefits that support jobs.

But what about the supposed work disincentive effect of the $600? Rigorous empirical studies show that any theoretical work disincentive effect of the $600 was so minor that it cannot even be detected. For example, a study by Yale economistsfound no evidence that recipients of more generous benefits were less likely to return to work, which is what we would expect to see if the extra payments really were a disincentive to work. And a case in point: in May/June/July—with the $600 in place—9.2 million people went back to work, and a large share of likely UI recipients who returned to work were making more on UI than their prior wage. The extra benefits did not stop them from going back. A job offer is too important at a time like this to be traded for a temporary increase in benefits, and when commentators ignore that, they are ignoring the realities of the lives of working people. Further, there are 8.5 million more unemployed workers than job openings, meaning millions will remain jobless no matter what they do. Dropping the $600 cannot incentivize people to get jobs that are not there. And, as Figure B shows, total continued claims in the most recent data are higher than they were when the $600 expired. It simply wasn't the $600 that was keeping people on UI, it was the fact that they can't find work.

Dropping the $600 is also exacerbating racial inequality. Due to the impact of historic and current systemic racism, Black and brown communities have seen more job loss in this recession, and have less wealth to fall back on. They are taking a much bigger hit with the expiration of the $600. This is particularly true for Black and brown women and their families, because in this recession, these women have seen the largest job losses of all. The Senate must extend the UI provisions of the CARES Act, both to provide relief to the jobless and to the bolster the broader economy.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Different economic crisis, same mistake: The Fed cannot make up for the Republican Senate’s inaction [feedly]

https://www.epi.org/blog/different-economic-crisis-same-mistake-the-fed-cannot-make-up-for-the-republican-senates-inaction/

Key takeaways:

- Following the Great Recession of 2008-2009, Congress did little to help recovery, and we relied almost exclusively on actions from the Federal Reserve to spur recovery. That was a mistake.

- It is Congress that has the tools that could end the economic crisis, and the Senate Republican caucus that is the roadblock to using these tools should be the focus of policy attention today.

- While the Fed has shown better judgement than Congress in the last economic crises, the tools they currently have are too weak to spur the needed recovery. In the end, there is no good substitute for a dysfunctional Congress—and today's dysfunction is caused by Senate Republicans who refuse to act.

The economic shock of the coronavirus is very different from the housing bubble shock that caused the Great Recession of 2008-2009. Yet six months into the current crisis, we are in danger of repeating a same key mistake: leaning too hard on the Federal Reserve to navigate the crisis while ignoring the much more important role of a bloc in Congress that is blocking needed aid. While it is true that the Fed has shown better judgement over the course of this crisis, the tools it currently has available to address it are weak. The tools Congress has are strong, but their actions have been stymied by the mystifyingly bad judgement of Senate Republicans.

The Fed is an enormously powerful institution in many ways, but their policy tools are actually quite limited for boosting the economy out of a recession or even increasing the rate of growth during recoveries. The Fed can decisively slow economic expansions, and too often in the past they have done this explicitly to weaken workers' bargaining position and keep wage-driven pressure on prices from forming. In short, the Fed has a powerful brake but a very weak accelerator, and their use of this brake has merited much criticism in the past.

If the Fed is relatively weak in its ability to end recessions, why do its actions get so much attention during times of economic crisis? Mostly because the actions of Congress (dominated for the past decade by the Republican caucus in the Senate) have been either too weak or outright damaging during these crises. For example, in the weak recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-2009, austerity imposed by a Republican-led Congress throttled growth, even as historically aggressive actions by the Fed tried (only partly successful) to counter this fiscal drag. During this period, every new Fed decision about interest rate changes or quantitative easing (QE) sparked long and loud controversy, even while having a minimal economic effect. Yet the enormous cumulative damage of fiscal austerity stemming from Congressional actions like the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 merited just a tiny fraction of this debate. Yet the damage done by the BCA utterly dwarfed the small (if admirable) attempts by the Fed to push the economy back to recovery.

In the current moment, there has been plenty of debate about what the Fed should do differently to ease the economic crisis. But again, it is Congress—hamstrung by Senate Republicans' refusal to act—which has all the power to end this crisis. And "end this crisis" is not an overstatement. The playbook for dealing with the current economic crisis is pretty obvious: provide relief for families with workers put out of work by the shock for as long as labor markets remain damaged, direct resources to state and local governments whose revenues have been savaged by the shock just as spending demands have risen, and spend every last dollar that would be useful for getting the virus under control. If the federal government is currently too dysfunctional to figure out how to spend these dollars to control the virus, then this means the aid to state and local governments should be that much greater.

Congress provided genuinely transformative relief to families in the CARES Act passed in March, but they cut off the aid far too early, assuming unrealistically that the virus would be under control in a matter of weeks. But for three months, the United States had a relatively generous and protective welfare state. There is no reason why Congress should not have continued this aid to families and provided generous and open-ended aid to state and local governments as well.

Some have argued that transferring resources to state and local governments is a power the Fed actually does have today, and that the Fed should take the lead on this. Some of these arguments are transparently cynical and meant only to justify congressional inaction. Others are more serious, and the Fed does have some scope here, but, again, the weaknesses of the Fed's tools are too often underappreciated. Essentially, the Fed has the power to make loans, not grants. Their current program that makes loans to state and local governments—the municipal liquidity facility (MLF)—charges these governments more than market interest rates for debt. From an economic point of view, this is clearly dumb—the Fed should try to make these loan terms as generous as possible.

But, it is telling that state and local government debt even outside the MLF does not seem to be growing very fast even with interest rates in these markets very low (after some hiccups in those markets in March and April, which were largely tamped down by the Fed's promised interventions). This was also true during the recovery from the Great Recession—very low municipal bond interest rates did not lead to a burst of state and local borrowing to support spending. What this should tell us is that the level of interest rates is not the real constraint here. Instead, it is state accounting and budget rules (set by law or in state constitutions) that provide a large hurdle for states thinking of taking on debt, whether market-based debt or debt through loans provided by the MLF. There is also ideology: The Republican electoral wave in 2010 led to governors and legislatures that were not going to spend more money regardless of how low interest rates on municipal bonds were.

If the Fed made radically large changes in how generous the terms of the MLF were (way beyond tweaking interest rates), would policymakers start quickly rewriting these state and local budgeting rules and begin piling on debt? For example, if the Fed charged negative interest rates on the loans and said that governments had 100 years to pay them back? From an economic viewpoint, this would indeed provide substantial relief to state and local governments. But, there are federal laws governing the loans the Fed can make, and it is far from clear that this would pass legal muster. While I wish it would pass muster—and I'm not that worried about the legality of this from a moral perspective—I worry that the Fed effectively usurping authority from Congress could spur Congress to respond with legislation that affirmatively reduced the future scope for the Fed to intervene during crises. Senate Republicans have made it very clear in the current moment that they do not want aid transferred to state and local governments. If the Fed declared it had the power to effectively transfer this aid and bypass Congress, would these Senators really sit idly by? This is a real potential cost to be reckoned with by those arguing for the Fed to test their legal limits super aggressively.

It's obvious why many focus on the Fed and wish it would be more transformative in helping the economy out of crises—the Fed has cleared the very low bar of showing some level of competence and judgement in recent crises, while Congress has completely stumbled. But it's Congress that has the tools needed to end the crisis, and it can use them anytime it wants. They—and the Senate Republican caucus that is the roadblock to using these tools—should be the focus of policy attention today. They shouldn't be let off the hook simply because we presume they're too incompetent (or malevolent) to be expected to act responsibly.

If a better Congress doesn't appear, it may well be the case that we need to think hard about giving the Fed more effective tools to fight recessions in the future. It's not impossible economically—we could give the Fed the legal right and administrative tools to transfer resources directly to people. But giving the Fed these expanded tools would require Congress to affirmatively grant them. In the end, there is no end-around a Congress that refuses to do what's right for U.S. families.

-- via my feedly newsfeed