https://www.epi.org/blog/there-is-no-justification-for-cutting-federal-unemployment-benefits-the-latest-state-jobs-data-show-the-economy-has-not-fully-recovered/

Key takeaways:

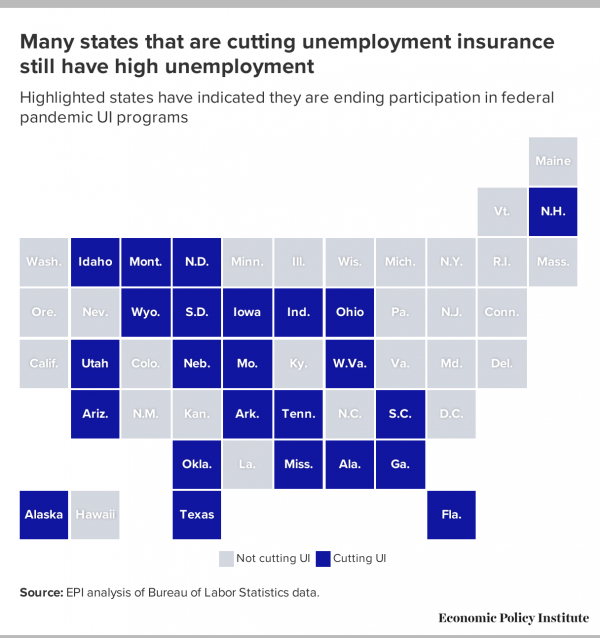

- There are still nearly 10 million people actively looking for work and unable to find it. April state jobs and unemployment data released last Friday show that in many of the 24 states—led by Republican governors—that are cutting federal unemployment insurance (UI) programs, labor market conditions look similar to the national picture.

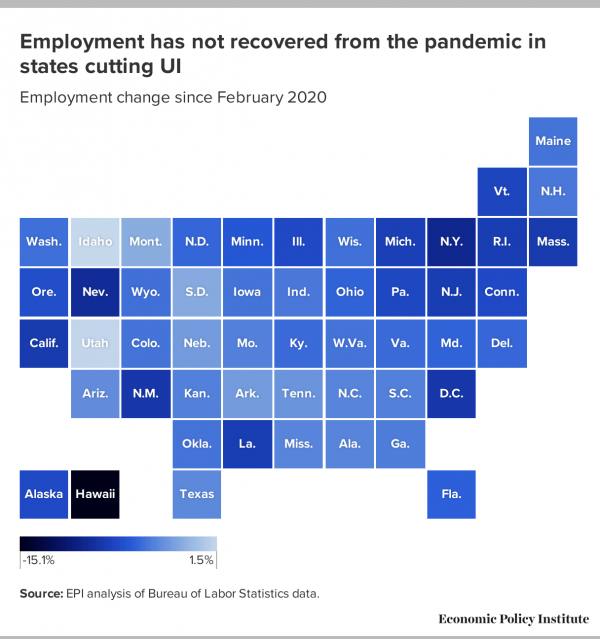

- The data likely understate the weakness of these labor markets, as labor force participation has fallen since the pre-pandemic level. And nearly all the states cutting UI still have significantly fewer jobs than before the pandemic.

- Those still filing for these benefits are the workers that need them the most, due to care responsibilities, health concerns, or other factors. Governors cutting off these key supports for these workers are not acting in the long-term best interest of any state's workers or businesses.

Republican governors in 24 states—including Florida and Nebraska just this week—have indicated they will pull out from the federal unemployment insurance (UI) programs created at the start of the pandemic. Some states are ending participation in all federal pandemic UI programs, others only some of the federal supports. These actions are dangerously shortsighted.

UI provides a lifeline to workers unable to find suitable jobs, giving them time to find work that matches their skills and pays a decent wage. Moreover, the money provided through these entirely federally funded programs bolsters consumer demand and business activity in local economies, helping to speed the recovery. In many states, these federal UI programs are providing the bulk of all unemployment benefits to jobless workers. By cutting off these programs—which currently provide an extra $300 in weekly benefits, allow workers who have exhausted traditional UI to continue receiving benefits, and expand eligibility to workers typically not included in existing UI programs—governors are weakening their states' potential economic growth.

Further, the most recent national jobs and unemployment data show that the country has not yet recovered from the COVID-19 recession. In April, the country was still down 8.2 million jobs from before the pandemic, and down between 9 and 11 million jobs since then if you factor in the jobs the economy should have added to keep up with growth in the working-age population over the past year.

With an official unemployment rate of 6.1%, there are nearly 10 million people actively looking for work and unable to find it. These estimates understate the true level of weakness in the labor market as many people have exited the labor force since the COVID-19 shock began, but would likely rejoin if jobs were available, and others are still awaiting recall from "temporary" layoffs. The country is simply not at a place yet where states should be cutting off supports to unemployed workers.

April state jobs and unemployment data released last Friday show that in many of the states that are cutting unemployment programs, labor market conditions are not much stronger than the national picture. Figure A shows the states that have indicated they will be cutting support for jobless workers. In four of these states, the unemployment rate in April was higher than the national average: Arizona (6.7%), Alaska (6.7%), Texas (6.7%), and Mississippi (6.2%). In another four states, the official unemployment rate was still 5% or above: West Virginia (5.8%), Wyoming (5.4%), South Carolina (5.0%), and Tennessee (5.0%).

However, these estimates likely understate the true weakness in these states' labor markets. In seven of the eight states mentioned above, and in 20 of the 24 states cutting UI, labor force participation has fallen since before the pandemic—in some cases, dramatically. The labor force participation rate has fallen by an average of 1.1 percentage points among the states cutting UI, with declines as large as 3.8% in Iowa, 2.1% in Montana, 2.0% in Florida, 1.9% in Nebraska, and 1.8% in Texas. Some of these declines may be the result of jobless workers opting for early retirement, but it is likely that most have given up looking for work in the face of few suitable options, valid concerns about health risks, or a need to provide care to a child or family member.

Nearly all the states cutting UI still have significantly fewer jobs than before the pandemic. Employment is down by an average of 3.5% since February 2020 in these states. Factoring in the jobs that these states would have needed to keep up with working-age population growth, employment is 4.8% lower, on average, than where we might expect it to be had there been no recession.1 Data for individual states are available in Figure B. In states cutting UI, the jobs deficit—the difference between the current level of employment in the state and the level we would expect had job growth kept pace with population grown since February 2020—ranges from a low of 12,000 jobs in South Dakota (or 2.8% of April 2021 employment) to 678,000 jobs in Texas (or 5.4% of April 2021 employment).

The most recent decisions by Texas and Florida to cut unemployment benefits are particularly egregious. Texas's unemployment rate is still three percentage points above its pre-pandemic unemployment rate. The state has nearly one million people that are officially unemployed—people actively looking for jobs, but unable to find work. Florida's unemployment rate is 1.5 percentage points above its pre-pandemic rate, with nearly half a million people officially unemployed. Since February 2020, 150,000 people have left the labor force in Texas and nearly 220,000 have exited in Florida.

Claims that the federal UI programs are preventing businesses from finding staff are unsubstantiated by the evidence. Multiple empirical studies have found that expanded unemployment benefits have not meaningfully constrained job growth. In fact, the sectors where generous UI benefits would be most likely to encourage workers to stay out of the workforce would be low-wage sectors, like leisure and hospitality. Yet, that is the sector that experienced the fastest growth in April. The central problem remains a lack of sufficient jobs for everyone that is out of work.

There may be areas where some employers are struggling to staff positions, but the likely obstacle is not overly generous UI benefits—instead it is wage offerings that are too low to make these jobs attractive. As my colleagues Heidi Shierholz and Josh Bivens note:

"Many face-to-face service-sector jobs have become unambiguously worse places to work over the past year. This has in no way been fully restored to the pre-COVID normal, as the coronavirus remains far from fully suppressed. Well-functioning labor markets should account for this degraded quality of jobs by offering higher wages to induce workers back. If enhanced UI benefits and a demand-increasing dose of fiscal stimulus are allowing these higher wages to be quickly offered in the face of supply constraints, then it seems like they're improving labor market efficiency in this regard."

In other words, if some workers are opting to pass on low-paying, potentially dangerous, or otherwise undesirable jobs while they look for something better suited for their skills or circumstances, that's a positive, economy-enhancing feature of a strong UI system.

As the threat from the pandemic fades and businesses resume regular operations, more workers are returning to work and fewer will need to rely on unemployment programs. In every state, the volume of weekly unemployment claims filed has fallen significantly from peaks earlier this year. On average, the total number of initial claims for both regular UI and pandemic unemployment assistance (PUA) have fallen 30% and 38%, respectively, since the beginning of February.2 Continued claims for both programs have fallen similarly.

But those that are still relying on these programs are likely those that need them most—the people having the hardest time finding suitable work or facing significant constraints on their ability to resume working due to care responsibilities, health concerns, or other factors. Cutting off adequate supports to these workers to try to force them to take whatever job might be available—even if it is low-paying, high-risk, not suited to their skills, or incompatible with their responsibilities at home—is cruel and not in the long-term best interest of any state's workers or businesses.

1. Author's calculation using Local Area Unemployment Statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

2. Author's analysis of unemployment insurance data from the U.S. Department of Labor. Values describe the change in the six-month rolling average of claims since the first week of February. Reporting of UI claims for some states is highly volatile, and subject to delays and errant reporting. This range reflects averages having removed a handful of clear outlying values, such as spells of reporting zero claims followed by enormous increases that are likely delayed reporting.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

No comments:

Post a Comment