https://equitablegrowth.org/what-the-coronavirus-recession-means-for-u-s-public-sector-employment/

According to the latest Employment Situation report released by Bureau of Labor Statistics today, the U.S. economy in September added 661,000 nonfarm payroll jobs, reflecting an important slowdown in employment growth. Also known as the Jobs Report, the release shows that the share of 25- to 54-year-old prime-age workers who have a job fell from 75.3 percent in August to 75.0 percent, and the number of unemployed workers who report being on a permanent layoff increased by 345,000 for a total of 3.8 million workers out of 12.6 million unemployed workers in September.

This final Jobs Report before the 2020 presidential election calls into question what policies are needed to foster an equitable and sustained economic recovery in the midst of the coronavirus recession. The report also reflects U.S. labor market conditions more than a month after the expiration of the $600 "plus-up" in unemployment benefits funded through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The end of this plus-up is forcing workers to return to work during an uncontrolled pandemic with few other options to support themselves and their families.

As such, there continue to be important income, race, and gender disparities evident in the latest Jobs Report, as well as questions about the quality of jobs being added that underlie last month's net job gains.

At 7 percent, White workers' unemployment rate is well-below the 8.9 percent jobless rate for Asian American workers, the 10.3 percent jobless rate for Latinx workers, and the 12.1 percent jobless rate for Black workers. The unemployment rate for women, which was lower than the jobless rate for men just before the onset of the coronavirus recession, stands 0.3 percentage points above it, at 8 percent. Additionally, 865,000 women dropped out of the labor force in September, and therefore are no longer counted among the ranks of the unemployed. Longstanding disparities along the lines of race, ethnicity, and gender continue to be exacerbated amid the tenuous economic recovery.

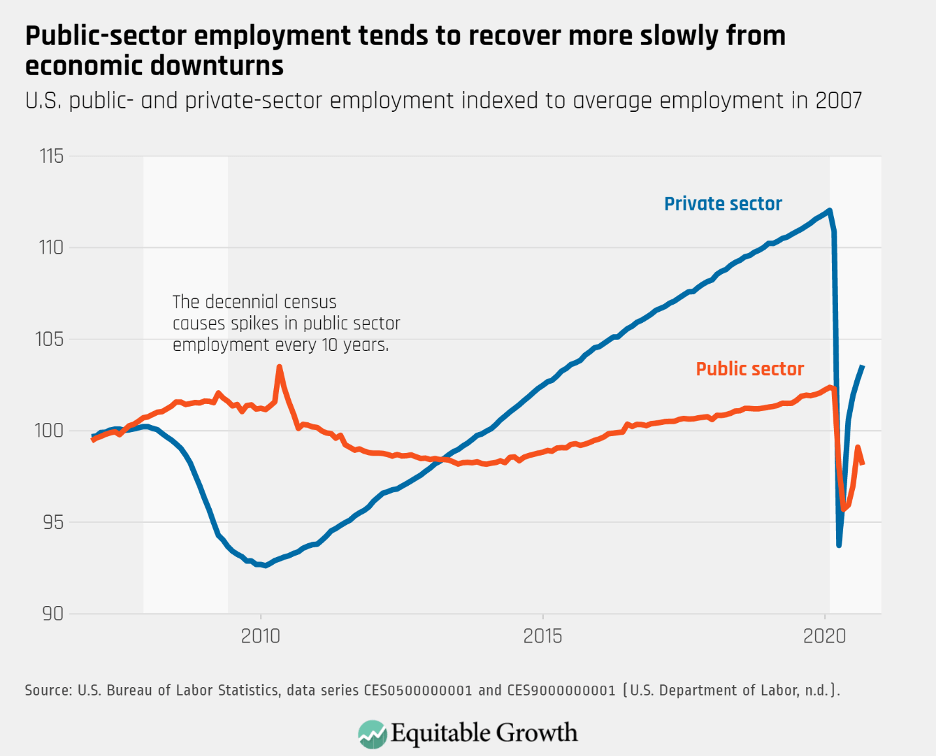

So far, employment losses in the public sector are not as deep as in the private sector, but they are worrying given that government is the only major sector to have experienced net losses last month, shedding 216,000 jobs in September. Additionally, the public sector was exceptionally slow to recover from the previous economic downturn. Even though the private sector also took a harder hit during and immediately after the Great Recession of 2007–2009, jobs were back to their pre-crisis level by March 2014. In contrast, government employment did not fully bounce back until late 2019, excluding a brief spike in 2010 due to hiring for the past decennial Census. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The crisis in the public sector also threatens many good jobs. Government workers tend to be less likely than their private-sector counterparts to experience either job losses or poverty, and have greater access to employee benefits such as healthcare. At 33.6 percent, the union membership rate of government workers is five times greater than for private-sector workers. Since the 1960s, effective enforcement of equal opportunity employment policies and greater political power led to a rise in the share of Black workers holding government jobs, making the public sector an important pathway to economic mobility and security for many marginalized workers.

Over the past few decades, however, public-sector jobs are becoming more insecure and less effective at promoting equitable labor market outcomes—a process that Great Recession of 2007–2009 seems to have accelerated.The past 40 years are marked by a shift from decent to lousy jobs, with both the decline in public-sector job quality and the loss of government jobs through recessions contributing to rising economic inequality. Research by Kimberly Christensen of Sarah Lawrence College, for example, shows that the fiscal crunch faced by state and local governments in the aftermath of the Great Recession was particularly damaging for women workers and workers of color because it shifted employment from good government jobs to much more precarious work in retail, leisure, and poorly paid medical care work.

Even though government jobs used to serve as a buffer against U.S. labor market inequality, their equalizing effect weakened over time. When analyzing racial disparities in the likelihood of being laid off, Elizabeth Wrigley-Field of the University of Minnesota and Nathan Seltzer from the University of Wisconsin-Madison find that Black workers are more likely to involuntarily lose their jobs than White workers, a disparity that has increased since the 1990s. The public sector used to reduce Black workers' disproportionate exposure to layoffs, but it became less protective over the past three decades, the authors find.

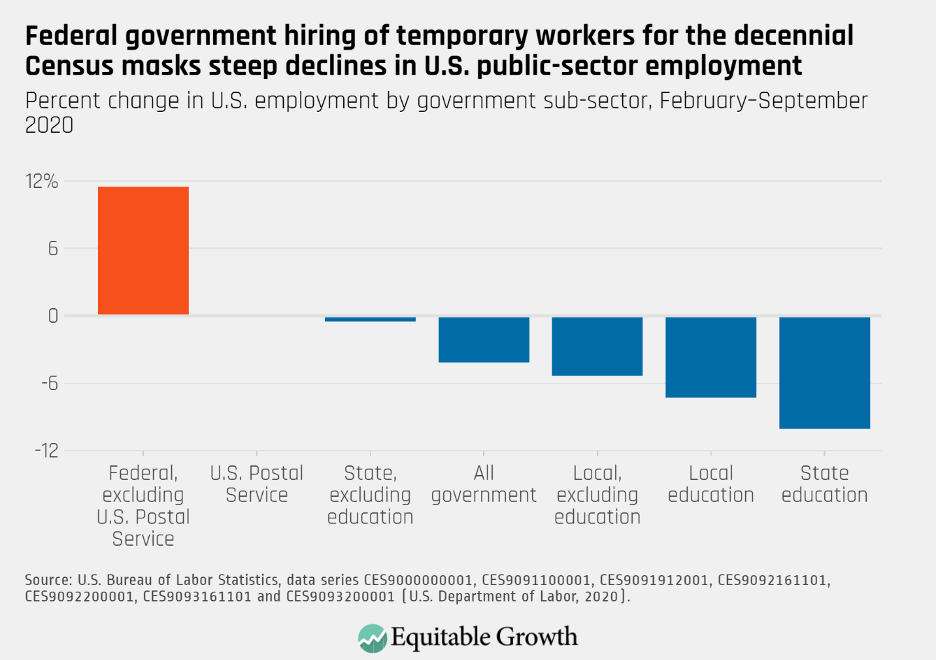

The great majority—63 percent—of public-sector workers are employed in local governments, compared to 23 percent in state governments and 14 percent in the federal government. This means local and state government workers—among whom women and Black workers make up a larger share of the labor force than in the federal government—are once again experiencing the deepest job losses because states are required to keep balanced budgets without debt financing.

In addition to the downward pressure on state and local employment in recessions, the increase in federal employment over the past 6 months is due to this year's decennial Census staffing. This staffing is now beginning to wind down. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Another slow recovery in the public sector—a sector in which Black workers, women workers, and union members are overrepresented—would put the brakes on the economic security they and their families need to climb out of the coronavirus recession, deepen existing U.S. labor market disparities, and become a drag on the economic recovery, as consumer spending declines as more quality jobs disappear.As state and local governments struggle with deep revenue and budget shortfalls, greater fiscal support to state and local governments is essential.

In addition to the unique risks facing the public sector, the private sector faces challenges to continuing jobs growth as well. These challenges exist in the public sector, too, particularly jobs such as Kindergarten through 12th grade school teachers, but private-sector service jobs that require face-to-face interaction or require close proximity to one's co-workers during an uncontrolled pandemic means that many of the recent jobs gains remain precarious.

Without sweeping and coordinated public health measures in place and effective treatments and vaccines for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, the number of additional jobs gained amid this tenuous economic rebound is fragile, and these jobs remain hazardous. The upshot: This continuing recession is still exacerbating long-term trends of decreasing job quality and rising economic precarity, which are especially harmful to marginalized workers, including Black workers and women workers, and their families, particularly amid a still-lethal pandemic.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

No comments:

Post a Comment