https://www.epi.org/blog/calls-to-establish-a-regionally-adjusted-federal-minimum-wage-are-dangerously-misguided/

We need to raise the federal minimum wage. Its deterioration in value over the past five decades has exacerbated poverty, widened inequality, and lowered wages for the bottom third of wage earners1—despite the fact that these workers typically are older and have more education than their counterparts a generation ago.

One misguided critique of the effort to raise the federal minimum to $15 in 2025 is that there is a need to establish a regionally adjusted federal minimum wage. In fact, federal minimum wage policy has always provided for tailored standards, by coupling a strong national wage floor with the ability for cities and states to adopt higher standards. Our ability to set a national wage floor is much easier now than it was decades ago when lawmakers last raised the federal minimum wage to new heights. In 1968, when the federal minimum wage was lifted to its highest value in U.S. history and coverage of the law was vastly expanded, there were much larger differences in wage levels throughout the country. Yet, we now have empirical evidence that establishing this unprecedented, nationwide minimum wage did not have adverse employment impacts.

Today, the wage levels of lower-wage states, primarily Southern ones, are much closer to overall national wage levels, so there is even less validity to claims that the federal minimum wage must be lowered to accommodate certain areas. Moreover, the 'bite' of a $15 minimum wage in 2025—i.e., the share of workers and businesses impacted, and the magnitude of resulting wage increases—will be well within the range of recent experiences of minimum wage increases in states and localities that studies have shown had little, if any, impact on employment. The proposed increase to $15 by 2025 will lead to improved annual earnings for nearly all low-wage workers.

$15 in 2025 is an appropriate level for the federal minimum wage

A $15 minimum wage in 2025 would be an appropriate and economically manageable level for the national wage floor. Data from EPI's Family Budget Calculator—which compiles the typical costs of basic necessities throughout the country—show that by 2022, there is not a county in the U.S. where an individual working full time, year round could achieve a secure standard of living earning less than $15 per hour.

Moreover, $15 in 2025 is the equivalent of $13.79 in today's dollars. Taking the federal minimum to this level would be an increase of about 30% above the 1968 peak, when the minimum wage was worth the equivalent of $10.59 in today's dollars. Over the past 50 years, productivity—the value of goods and services produced from each hour of work in the economy—has more than doubled. The minimum wage should be set at a level that ensures all workers, including those in the lowest-paid jobs, benefit from the economy's increased capacity to generate income—particularly when low-wage workers today tend to have higher levels of education than their counterparts in the 1960s.

Setting regional thresholds is bad policy and would cement racial and gender wage disparities

The argument that it would be better to adapt the federal minimum wage to local conditions is described as avoiding a 'one-size-fits-all' policy imposed on states regardless of local conditions. That is a mischaracterization of federal policy, however, since there is wide variation in minimum wages across states and localities (where states permit) as subnational governments adopt higher standards. The purpose of federal law is to set a national floor which provides a living wage to all workers and brings wages in lower-wage states closer to those in higher-wage areas.

It is critically important that the federal standard not be set to normalize or tolerate existing low-wage conditions in particular regions, industries, or occupations that are largely the result of historical racism and sexism. When the first federal minimum wage was being debated in the 1930s, Southern congressmen strongly opposed the federal standard, concerned that it would upset the white supremacist plantation system that dominated the South's economy. In fact, Southern lawmakers insisted that the federal wage standard should be adjusted by region to account for differences in costs of living. What ultimately led to the minimum wage law's passage as a single national wage floor was a "compromise" with Southern Democrats to exempt agriculture, restaurants, and a host of other service-sector industries that disproportionately employed Black workers. Even after it was amended in 1967 to cover more of these industries, the law still exempted most farmworkers—who today are majority Latinx—and allowed employers to pay a subminimum wage to tipped workers—who today are overwhelmingly women.

Adjusting the federal minimum wage based upon regional wage differences would serve to cement racial and gender wage disparities. Indeed, when we last analyzed a proposal to regionally adjust the federal minimum wage, we found that Black workers would be particularly harmed and women of color were a disproportionate share of those left behind, relative to a federal minimum wage without any regional adjustment.

Raising the minimum wage to its historical peak in 1968 had no adverse effects on employment

The 1966 amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act expanded coverage of the federal minimum wage to over a fifth of the U.S. workforce that was previously exempt and raised the federal minimum wage to its highest level ever by 1968—the equivalent of $10.59 in today's dollars. In their groundbreaking 2020 study, Ellora Derenoncourt and Claire Montialoux find that the expansion of the minimum wage to previously exempt industries in 1967 raised wages of affected workers by an average of 34%, and dramatically reduced the Black-white earnings gap. They note, "the wage effect on treated [affected] workers is large because before 1967, many of them (predominantly Black workers) were employed at wages far below the federal minimum wage." Despite these large, government-mandated wage increases, the researchers found "a near-zero effect on employment."

Low-wage states have caught up since 1968

If the highest federal minimum wage in history—accompanied by the largest expansion of coverage since the law's enactment—had no measurable effect on employment, there is even less reason to think a strong national wage floor would yield negative effects today. As we explained in a 2015 paper, "The wage distributions across the U.S. states are closer together now than they were five decades ago. As a result, a federal minimum wage has a smaller 'bite' today in low-wage states than was the case in 1968. This should help to allay concerns that a higher federal minimum wage would hurt employment in low-wage states."

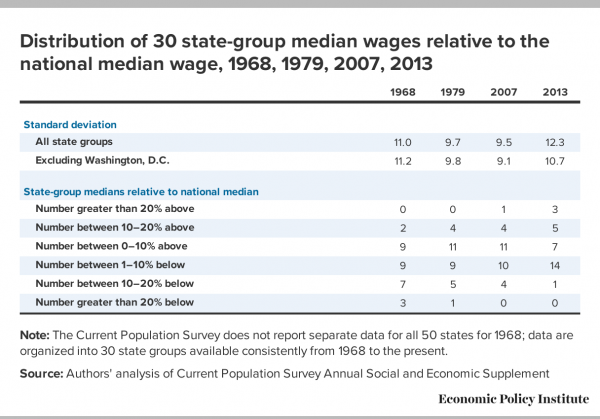

This can be seen in Table 1 from our earlier study. There has been a convergence of state median wages—primarily because state medians at the bottom have closed the gap with the national median. In 1968, there were 10 of the 30 state groups examined (the data grouped some states together) that had a median wage at least 10% below the national median and four state groups with a median more than 20% below the national median. By 2013, there was only one state group (Oklahoma and Arkansas) with a median wage more than 10% below the national median. This implies that any given minimum-wage level will have less of a differential impact now on low-wage states relative to high-wage states than would have been the case in 1968.

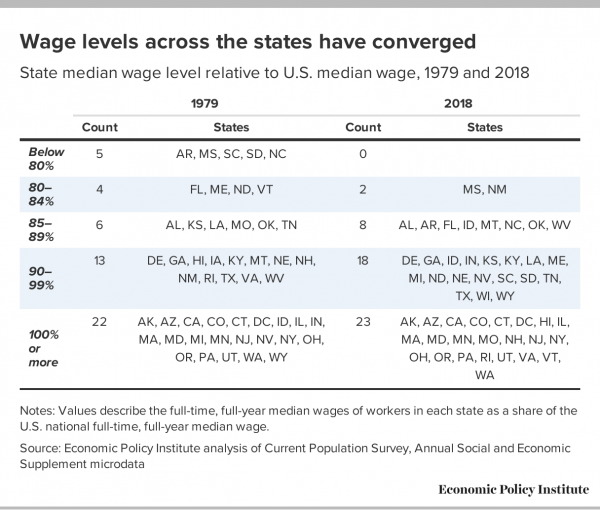

In Table 2, we repeat this analysis from 1979 to 2018 using data on the median hourly wage of full-time, full-year workers in the Current Population Survey March Supplement, which allows us to identify each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The data affirm a similar convergence of wages across the country since the 1970s. In 1979, there were five states with a median hourly wage more than 20% below the national median and there were no such states in 2018. States are increasingly clustered within 10% of the national median. As mentioned earlier, this eases the challenge of adopting a strong national standard across the country.

The suggestion for regional minimum wage thresholds is also sometimes offered as tailoring the threshold to local price levels. However, price differences across localities are reflected in the difference in their respective median wages and so are captured by the analyses in Tables 1 and 2.2

Some localities within states may have lower wages than the state as a whole, but analyses of local minimum wage impacts consistently show that higher minimum wages have not led to meaningful job losses, even at the local level. For example, Anna Godoey and Michael Reich examined the impact of higher minimum wages in low-wage counties, where the new minimum wage was as high as 82% of the area median wage. They found no evidence of negative employment effects. Similarly, Arindrajit Dube and Attila Lindner find that city-level minimum wages have raised wages of low-wage workers with "negligible" impact on employment.

What matters most is that higher minimum wages boost workers' annual earnings

Discussions around possible employment effects typically ignore the key metric for evaluating the utility of higher minimum wages: what happens to workers' annual earnings? As we explained in this 2018 paper, turnover in low-wage industries is high and low-wage workers frequently cycle in and out of jobs over the course of a year. If, in some areas, a higher minimum wage did negatively effect jobs, that doesn't mean low-wage workers would suddenly become jobless and never work again. The more likely scenario is that workers might see some reduction in their total work hours over the year—either from reduced schedules or more time in between jobs. But, because their hourly earnings are much higher, most affected workers earn as much or more than before over the course of the year, even if they are working less. Indeed, research on the minimum wage's effect on family incomes shows that higher minimum wages unambiguously raise low-wage workers' annual income, regardless of how their work hours may have changed.

Conclusion

The notion of adjusting federal wage standards based on local conditions sounds reasonable at first glance, but a more extensive examination suggests it is both unnecessary and could end up normalizing low wages in certain regions that reflect historic and current wage hierarchies established to hold Black workers' wages down. Federal minimum wage policy should continue to be set with a strong national floor supplemented by higher wage standards adopted by cities and states. Establishing a strong national floor is easier now than in past decades when Congress took the federal minimum wage to new peaks, because wage differences across states have declined substantially. Given the evidence that higher minimum wages do not have adverse employment impacts, especially when one looks at the annual earnings of low-wage workers, there is no reason why we should not enact a $15 national wage floor by 2025.

1. Authors' calculations using Economic Policy Institute Minimum Wage Simulation model.

2. For example, a simple correlation of state median wages with the Bureau of Economic Analysis's 2018 Regional Price Parity indices (which measure differences in state prices relative to the national average) returns a correlation coefficient of 78%. For all states, the ratio of the state median wage to the national median wage is within 1.1% of that state's regional price index.

-- via my feedly newsfeed