A few common explanations dominate the discussion of rising earnings inequality in the United States. Automation and computerization, for example, have augmented many nonroutine white-collar jobs—meaning those jobs can pay more—while replacing more routine jobs. Tech pays off differently depending on your occupation. Another set of explanations of earnings inequality has to do with the types of employers, workplaces, or firms that make up the U.S. economy. Low-paying service-sector employers have multiplied, and manufacturers have deunionized, outsourced, or offshored, while a select few firms in finance, consulting, and tech pay disproportionately high wages. This last set of firms is made up of so-called superstar firms.

In short, where you work matters for earnings inequality, too—it's not just what you do at work.

In a new paper, we argue that these two types of explanations miss something crucial. From 1999 to 2017, increasing earnings inequality occurred not mainly because of changing pay-offs to where you work or what you do at work. Instead, inequality is increasing through the increased alignment between occupations and workplaces. High-paying occupations are increasingly clustered at high-paying workplaces, and low-paying occupations are increasingly located at low-paying workplaces.

This alignment between earnings at workplaces and occupations exacerbates overall earnings inequality. But this has largely escaped public attention because we typically study either occupations or workplaces in isolation.

For our analysis, we used restricted-use Occupational Employment Statistics, or OES, survey data collected by the U.S. Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics. Twice a year, the BLS surveys about one-sixth of establishments in the United States, asking them to list the occupations they employ, the number of workers in each occupation, and the wage distribution of each occupation. So, the OES data let us examine the role of both workplace and occupation in earnings inequality—something that other sources of U.S. data cannot do.

Using this survey's data, we modeled workers' earnings as the sum of both occupational premiums and workplace premiums. An occupation premium is what a certain occupation pays beyond the average, once you take into account the workplaces where it is employed. A workplace premium is what a workplace pays beyond average, once you take into account the occupations it employs.

Here's an example. A software engineer working at the online vacation rental company Airbnb Inc. earns a lot, since software engineers in general are well-compensated and since Airbnb pays its employees above the rate they might earn elsewhere. A software engineer working at a nonprofit might earn less—even though that worker could still earn more than other employees at the nonprofit due to their occupation, the nonprofit as a whole pays less. So, software engineering has a high occupational premium, Airbnb has a high workplace premium, and the nonprofit has a lower workplace premium.

Using what's called a two-way fixed-effects regression, we calculate these two sets of premiums for every occupation and for every workplace in the OES survey. This approach lets us separate inequality between occupation premiums (due to skill-biased technological change, for example) from inequality between workplace premiums (due to superstar firms, for example).

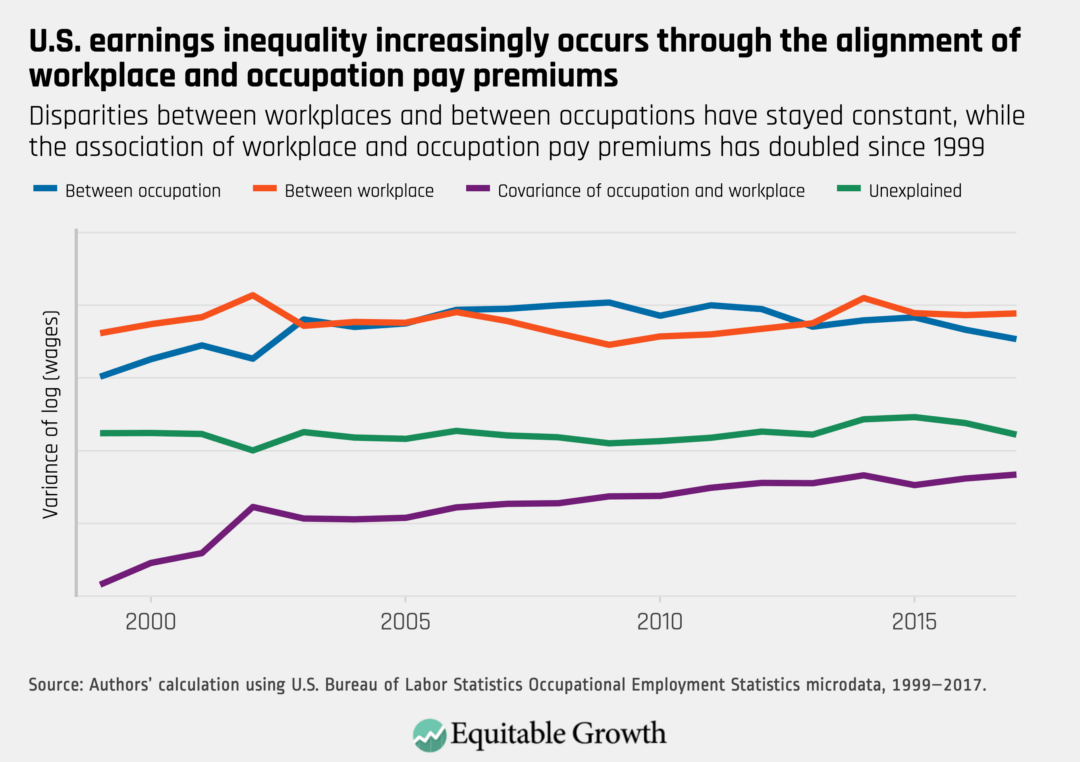

Surprisingly, we find that both between-workplace inequality and between-occupation inequality have stayed roughly level over the past 20 years, each explaining around the same amount of earnings variation. The big change has been in the covariance between occupation and workplace premiums, which has doubled in the past 20 years and which accounts for two-thirds of the total increase in wage inequality. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows that pay premiums are increasingly aligned such that highly paid occupations are more likely to be located at high-paying establishments, and similarly for poorly paid occupations and low-paying establishments. Workers with the high-premium occupations at high-premium establishments enjoy very high wages, while those with low-premium occupations at low-premium establishments receive very low wages. We call this the consolidation of workplace and occupation inequalities.

But why does consolidation matter?

Consolidation exacerbates overall earnings inequality, with those in high-occupation-premium, high-establishment-premium jobs earning extra and those in low-occupation-premium, low-establishment-premium jobs earning even less. The result is worse earnings inequality than either between-occupation or between-workplace variation would create by themselves. And, though we cannot test it with our data, consolidation could affect other aspects of work, too. While a janitor hired by Eastman Kodak Co. some 40 years ago could work her way into other jobs at the firm, a janitor at Apple Inc. today is actually employed by a custodial services contractor and has little chance for promotion.

The consolidation we observe means that many conventional explanations for rising earnings inequality do not capture the full story. Explanations emphasizing divergence between occupations or educational levels or explanations focusing on the importance of where you work ignore the fact that the two are increasingly tied together.

This earnings-inequality dynamic also means that policymakers need to look at more than one dimension of earnings inequality—occupation or workplace—at a time. Policies such as the minimum wage cut across both workplace and occupation at once: It doesn't matter whether it's the occupation premium or the workplace premium that's low. So, a higher minimum wage keeps low workplace premiums and low occupation premiums from compounding. Of course, the minimum wage alone isn't enough—most of the rise in inequality over the past 20 years is due to a growing gap between median-earning and high-earning workers.

So, policymakers should also consider interventions in the sectors where the consolidation of earnings inequality is most rampant. First is the service sector, which is increasingly dominated by low-paying workplaces employing primarily poorly paid occupations on the one hand (think fast-food restaurants), and very high-paying workplaces employing mainly well-compensated occupations (think consulting firms). Together, this shift in industrial composition accounts for more than 20 percent of the total increase in consolidation.

Second is the bifurcation of social services. Some hospitals, nursing homes, and the like have cut costs in recent years by shifting to a workforce of primarily poorly compensated occupations. An underresourced community health center, for example, may reduce the number of physicians on staff, relying instead on a workforce of nurses and other employees with less-prestigious credentials. Perhaps constrained by budget cuts, the health center also may pay its employees less across the board than they might earn elsewhere.

Meanwhile, other establishments in social services have shifted up, employing more professional elites and paying them well, too. Think of a small psychiatric practice with a primarily wealthy clientele. These patterns of down-shifting and up-shifting account for about 12 percent and 11 percent, respectively, of the total increase in consolidation, according to our working paper.

While most dramatic in these two sectors, earnings consolidation has occurred throughout the U.S. economy. Regardless of industry, the alignment of workplace and occupation now exacerbates overall earnings inequality. It forms a new source of earnings inequality, one which defies conventional explanations and which requires attention from researchers and from policymakers alike.