https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-14/oil-slump-worsens-lowflation-risks-central-banks-can-t-ignore

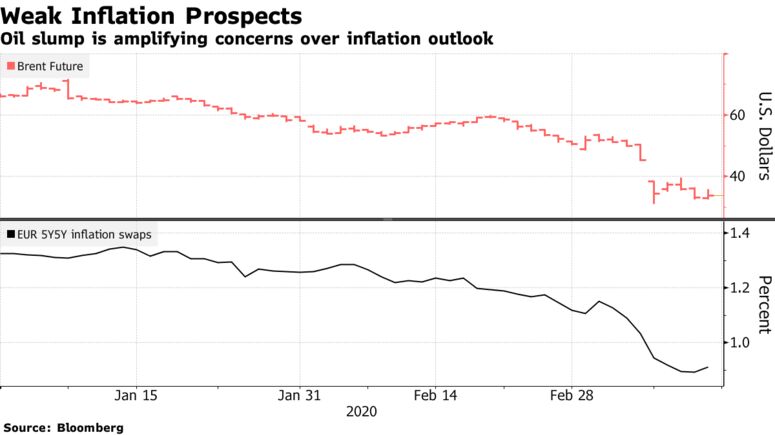

Global central banks already struggling to spur inflation amid the spreading coronavirus are facing a fresh challenge -- the oil crash.

The price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia that has given crude its worst week since 2008 will put heavy downward pressure on inflation just as the coronavirus outbreak hits consumer spending. It's undoing the years of effort that monetary authorities have put in, along with trillions of dollars of stimulus, trying to hit their price-stability targets.

The question now is whether they have the capacity to respond as strongly as needed. Market-based gauges of future inflation have slumped, suggesting that investors doubt they can, or that governments will provide sufficient support.

Central bankers tend to skirt over energy-price shocks if they think they'll be temporary, pointing instead to "core" inflation measures that exclude volatile components. After so many years of low inflation despite massive monetary stimulus, though, there's a risk that companies and households decide this is just the latest sign that prices will stay flat.

"There is a tendency to say oil is a temporary factor that central banks will look through, and won't affect their view of the appropriate stance of policy," said Jacob Nell, an economist at Morgan Stanley, who sees the oversupply of oil persisting. "It's harder for central banks to look through a fall in inflation when inflation expectations are so far off the target. They have to be more ready to respond, or they could risk credibility and it will be that much harder to get inflation back to target in future."

While an oil slump would normally boost purchasing power in the world's biggest economies -- Japan and the euro zone both import most of their energy, and the U.S. status as a net petroleum exporter is nascent and fragile -- this time the coronavirus outbreak is simultaneously hitting consumption and travel.

Brent crude prices were down about 24% this week despite monetary easing by central banks and pledges of fiscal support by governments. JPMorgan Chase & Co. economists say a 20% drop would typically add close to 1% to global output the next quarter, but now customers might not spend the windfall.

"Given the pullback in consumer demand in travel and entertainment, the actual boost to household purchasing power from falling oil prices could be less than usual," they said in a note. "In addition, falling oil prices raises financial-market risks by expanding the set of small and medium-sized enterprises facing concentrated credit stresses in the coming months."

Read more... |

Disinflation, as slowing inflation is know, isn't a given. Oil prices could rebound if Russia and Saudi Arabia resolve their differences. The coronavirus might actually prove inflationary if it disrupts companies so much that supply of goods and services falls more than demand.

Even after the virus outbreak subsides though, inflation still will be pressured by the trade war, depressed immigration into the U.S., automation, and other longer-term trends, according to David Mann, Singapore-based global chief economist of Standard Chartered Plc.

While productivity investment is expected to pick up sometime in the next decade, alongside implementation of 5G technologies especially in Asia, there's no reason to expect that ramp-up right now.

Euro-zone inflation slowed to just 1.2% in February, compared with a goal of just under 2%, and that was before the oil shock. The Bank of England says U.K. inflation rate could drop below 1%, to less than half its target.

Aside from India, where inflation remains above the 2%-6% target range, Asian economies broadly face weak pressures. Core consumer prices in China are rising at their slowest pace in almost a decade. Japanese inflation is 0.7%, and gains through February were actually driven by rising gasoline costs. Inflation gauges for Indonesia, Thailand and Singapore are all below-target or in the lower end of target ranges.

At Deutsche Bank AG, economists led by Matthew Luzzetti have dusted off a 2017 report which showed the oil price shocks of the mid-1980s and 2014-15 led to persistent declines in inflation expectations that were never unwound. They worry a third episode has now begun which will complicate the work of central banks.

"Inflation expectations at this point are extremely low -- arguably too low," said Mann of Standard Chartered. "They might not pick up for some time."

-- via my feedly newsfeed