http://cepr.net/publications/op-eds-columns/trump-has-been-giving-up-ground-in-his-much-vaunted-trade-war

Dean Baker

Truthout, October 14, 2019

With all the attention on the impeachment investigation against Donald Trump, his trade war is getting ignored by the media. Since the trade war is not going very well, that is probably a good thing for Trump.

Just to remind people, Trump made the trade deficit a major issue in his campaign. He claimed that our trading partners were ripping the U.S. off because of lousy trade deals crafted by stupid negotiators. He assured the public that he would use his negotiating skills to bring the trade deficit down. Now that he has been in office for more than two and a half years, it's worth seeing how the fight is going.

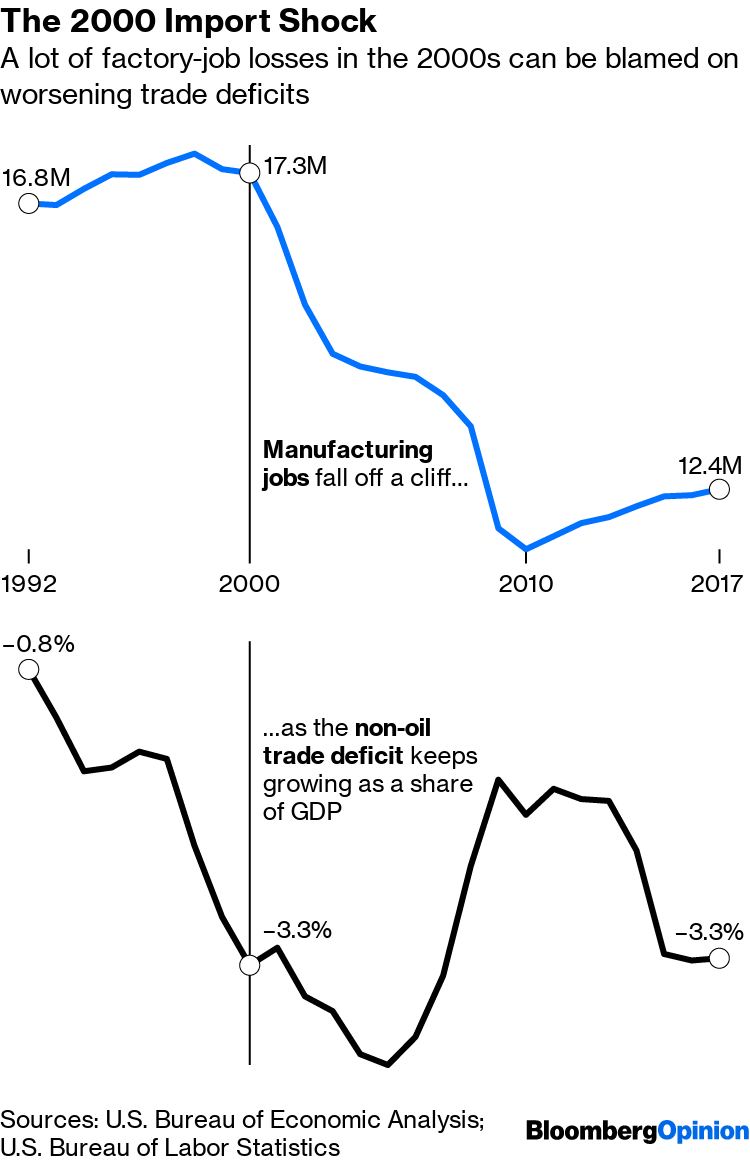

So far, it looks like Trump has been giving up ground. In 2016, the last year of the Obama administration, the trade deficit was $518.8 billion, or 2.8 percent of GDP. The trade deficit expanded in both 2017 and 2018, reaching $638.2 billion in 2018, or 3.1 percent of GDP. And it looks to come in slightly higher in 2019, with the deficit averaging $648.3 billion in the first half of 2019. This is clearly going the wrong way.

There are many factors behind the rise in the trade deficit. Growth in the U.S. has been somewhat faster than in major trading partners like the EU and Japan. The dollar has also risen in value, although most of that rise predates Trump. But we know that Trump wouldn't be interested in excuses. The bottom line is the trade deficit has gotten worse on Trump's watch.

The story does not look any better if we look at his major nemeses. Starting with China, in the last year of the Obama administration, the trade deficit in goods with China was $346.8 billion. This had increased to $419.6 billion last year. It looks like the trade deficit is coming down somewhat in 2019, with the deficit for the first eight months at $231.6 billion, compared to just over $260.0 billion over the first eight months of last year. Nonetheless, we are still likely to end up with a higher deficit with China in 2019 than we had in the last year of the Obama administration.

It is also worth remembering that it is difficult to calculate bilateral trade deficits with rigor. Suppose that iPhones, which had previously been assembled in China, are instead assembled in Thailand. If we imported the iPhone from China, the full value of the iPhone would have been recorded as an import from China, even though the assembly may have counted for less than 10 percent of the value added.

When the assembly shifts to Thailand, the reduction in our reported imports from China is equal to the full cost of the iPhones that we previously imported from China. The actual hit to China is just the small share of the value added that is attributable to assembly.

If Trump's battle with China is not going well, he seems to be doing even worse with other trade combatants. The trade deficit with Mexico was $63.3 billion in 2016. It hit $80.7 billion last year and is virtually certain to come in even higher in 2019. The trade deficit with the European Union was $146.7 billion in 2016. It had risen to $168.7 billion last year and is on a path to come in $10-$15 billion higher in 2019. The deficit with Canada rose from $11 billion in 2016 to $19.1 billion last year. It is likely to be roughly $1 billion higher in 2019.

It doesn't look like Donald Trump has had many successes in his trade war. That might be bad news for him politically, but it is probably good news for the country and the world.

While Trump made currency values a major issue in his campaign, yelling about "currency manipulation" by China and other countries, currency has largely fallen off his agenda in his trade disputes. Instead, he has put protecting the intellectual property of U.S. corporations front and center.

This is not a battle that most of us should want to see Trump win. Ordinary workers have no real interest in making people in China and elsewhere pay more for drugs, medical equipment, software, and other items to which US companies have intellectual property claims.

In fact, they would benefit from having these items sell in a free market without patent and copyright monopolies. They would also benefit from a system that facilitated the free flow of knowledge and technology, especially in the areas of clean technology and medicine. Since China has a considerably larger economy than the United States, a reasonable trade policy would be more focused on getting access to their innovations rather than protecting the intellectual property claims of US corporations.

So the report from the front is that Donald Trump is losing his trade war badly, and that is a good thing for people in the United States and the world.

-- via my feedly newsfeed