The Wealth Detective Who Finds the Hidden Money of the Super Rich

Thirty-two-year-old French economist Gabriel Zucman scours spreadsheets to find secret offshore accounts.

Gabriel Zucman started his first real job the Monday after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. Fresh from the Paris School of Economics, where he'd studied with a professor named Thomas Piketty, Zucman had lined up an internship at Exane, the French brokerage firm. He joined a team writing commentary for clients and was given a task that felt absurd: Explain the shattering of the global economy. "Nobody knew what was going on," he recalls.

At that moment, Zucman was also pondering whether to pursue a doctorate. He was already skeptical of mainstream economics. Now the dismal science looked more than ever like a batch of elaborate theories that had no relevance outside academia. But one day, as the crisis rolled on, he encountered data showing billions of dollars moving into and out of big economies and smaller ones such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Hong Kong, and Singapore. He'd never seen studies of these flows before. "Surely if I spend enough time I can understand what the story behind it is," he remembers thinking. "We economists can be a little bit useful."

A decade later, Zucman, 32, is an assistant professor at the University of California at Berkeley and the world's foremost expert on where the wealthy hide their money. His doctoral thesis, advised by Piketty, exposed trillions of dollars' worth of tax evasion by the global rich. For his most influential work, he teamed up with his Berkeley colleague Emmanuel Saez, a fellow Frenchman and Piketty collaborator. Their 2016 paper, "Wealth Inequality in the United States Since 1913," distilled a century of data to answer one of modern capitalism's murkiest mysteries: How rich are the rich in the world's wealthiest nation? The answer—far richer than previously imagined—thrust the pair deep into the American debate over inequality. Their data became the heart of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders's stump speech, recited to the outrage of his supporters during the 2016 Democratic presidential primary.

Zucman and Saez's latest estimates show that the top 0.1% of taxpayers—about 170,000 families in a country of 330 million people—control 20% of American wealth, the highest share since 1929. The top 1% control 39% of U.S. wealth, and the bottom 90% have only 26%. The bottom half of Americans combined have a negative net worth. The shift in wealth concentration over time charts as a U, dropping rapidly through the Great Depression and World War II, staying low through the 1960s and '70s, and surging after the '80s as middle-class wealth rolled in the opposite direction. Zucman has also found that multinational corporations move 40% of their foreign profits, about $600 billion a year, out of the countries where their money was made and into lower-tax jurisdictions.

Share of U.S. Wealth Held by the Top 1%

Data: Gabriel Zucman

Like many economists, Zucman and Saez have embraced the political implications of their research. Unlike many, they champion policy recommendations that are bold and aggressive. Before Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren started her 2020 presidential campaign by proposing a wealth tax, she consulted the pair, who estimated that her tax would bring in $2.8 trillion over the next decade. She conferred with them again before floating a corporate tax on profits above $100 million, which they calculated would raise more than $1 trillion over 10 years. Sanders came looking for their advice on his estate tax plan, which would establish rates as high as 77% on billionaires. And when New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposed on 60 Minutes to hike the top marginal tax rate to as much as 70% on income above $10 million, Zucman and Saez were fast out with a New York Timesop-ed in support.

The pair has now written a cookbook of sorts for any 2020 candidate looking to soak the rich. The Triumph of Injustice, to be published by W.W. Norton & Co. early next year, focuses on how wealth disparity can be fought with tax policy. The tools Zucman has identified to date challenge a series of assumptions, fiercely held by many economists and policymakers, about how the world works: That unfettered globalization is a win-win proposition. That low taxes stimulate growth. That billionaires, and the superprofitable companies they found, are proof capitalism works. For Zucman, the evidence suggests otherwise. And without taking action, he argues, we risk an economic and political backlash far more destabilizing than the financial crisis that sparked his work.

America's top wealth detective probes the secrets of the super rich in a tidy, white-walled office with an enviable view of the San Francisco Bay. His methods are unusually brute-force compared with those of recent-vintage U.S. economists, relying not on powerful computers, regression analyses, or predictive models, but on simple, voluminous spreadsheets compiling the tax tables, macroeconomic datasets, and cross-border-flow calculations of central banks. He does it on his own, only rarely outsourcing to graduate students.

"You can conduct this detective work only if you do it to a large extent yourself," he says. "The wealth is not visible in plain sight—it's visible in the data." Lately, he adds, the Bay Area humming outside his window, "I see more of Silicon Valley in my Excel spreadsheets, especially in the amount of profits booked in Bermuda and Ireland."

Born and raised in Paris, Zucman is the son of two doctors. His mother researches immunology, and his father treats HIV patients. Politics was a frequent dinnertime topic. He says the "traumatic political event of my youth" occurred when he was 15. Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the far-right National Front party, edged out a socialist candidate to win a spot in the final round of 2002 presidential voting. Zucman remembers joining the spontaneous protests that followed. "A lot of my political thinking since then has been focused on how we can avoid this disaster from happening again," he says. "So far, we've failed." (Le Pen's daughter made the presidential runoff in 2017 and won almost twice as many votes as her father.)

Zucman met his future wife, Claire Montialoux, in 2006, in a university economics class. She's now finishing her Ph.D. dissertation, which shows how the U.S.'s expansion of the minimum wage in the late 1960s and '70s helped black workers, narrowing the racial earnings gap. "We share the same vision for why we are doing social sciences," Zucman says. "The ultimate goal is how can we do better?"

His own graduate work in Paris saw him compile evidence that the world's rich were stowing at least $7.6 trillion in offshore accounts, accounting for 8% of global household financial wealth; 80% of those assets were hidden from governments, resulting in about $200 billion in lost tax revenue per year. At the same time, he was helping his adviser, Piketty, pull together more than 300 years of wealth and income data from France, Germany, the U.K., and the U.S. They co-authored a paper on the numbers, which became a key part of Piketty's surprise 2014 bestseller, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The following year, Zucman's doctoral research was also published as a book, The Hidden Wealth of Nations.

He arrived in the U.S. in 2013, the same year President Obama was declaring inequality "the defining challenge of our time." Zucman had been recruited to Berkeley by Saez, winner of economics' prestigious John Bates Clark Medal in 2009 and a MacArthur Fellowship in 2010. They took up offices next to each other and set about trying to solve the riddle of America's hidden wealth, unveiling their estimates as a draft paper the following year.

None of it was easy. Tax collectors such as the IRS generally require taxpayers to report income, not wealth. And much of the world's wealth is held in forms—homes, art, retirement accounts, non-dividend-paying stocks—that produce no income prior to a sale. A real estate mogul with a billion-dollar property portfolio and billions more in cash stashed overseas can still report a tiny income. Most inequality researchers therefore rely on voluntary surveys, which often fail to identify enough of the very richest, or data on the estate tax, which has gotten easier and easier to avoid.

Zucman and Saez started with the IRS. The agency opens its doors to researchers under strict conditions, and only Saez, a U.S. citizen, was allowed inside a facility, where he downloaded anonymized statistics up to the extreme end of the income scale. The duo then translated the data into wealth estimates. Saez had had the idea for a while. "I was doubting how that could actually be done, because there are so many complications," he says. "And then Gabriel came along." With each asset class, from equities and real estate to pensions and insurance, they painstakingly estimated the relationship between income and wealth in the U.S., checking and tweaking based on data from external sources.

They found that something cataclysmic happened around 1980. As Ronald Reagan was winning the White House, the top 0.1% controlled 7% of the nation's wealth. By 2014, after a few decades of booming markets and stagnant wages, the top 0.1% had tripled its share, to 22%, a bit more wealth than the bottom 85% of the country controlled. The data showed the extent of the problem and the absence of a solution: In the aftermath of the financial crisis, while middle-class Americans were burdened by job losses and debt, the rich had swiftly resumed their party. Wealth that had vanished from financial markets after Lehman's collapse had reappeared, doubling and tripling the portfolios of well-off investors.

U.S. Wealth Distribution, 2014

Data: World Inequality Database

Some eminent economists, including the University of Chicago's Amir Sufi and Nobel laureate and New York Timescolumnist Paul Krugman, endorsed the findings, but others were skeptical. The new numbers were much higher than previous estimates, including those of the Federal Reserve's Survey of Consumer Finances, which is based on detailed responses provided by Americans and is widely considered the best measure of U.S. wealth.

The disputes over Saez and Zucman's methodology were highly technical. Fed economists said the Berkeley pair were underestimating the investment returns the very rich were earning, which had the counterintuitive effect of overestimating the fortunes from which they drew their income. Saez and Zucman rejected that criticism but made other adjustments to their method and updated the numbers to reflect revised macroeconomic data. Their estimate of the 0.1%'s wealth share dropped a couple of percentage points, to about 20%, still a startling figure. Then, in 2017, the Fed released a survey incorporating methods it said better captured the wealth of the very rich; the central bank cited Zucman and Saez's work in an accompanying paper. Its latest figures showed a jump in inequality, with the top 1%'s share rising from 36% in 2013 to 39% in 2016, matching the pair's estimate.

At conferences and seminars, Zucman's peers still occasionally sound baffled by his work. Economists often aim for precise, unassailable conclusions, but he's "comfortable getting a 'rough justice' answer to a question" if it helps fill in a big gap in knowledge, says Reed College economics professor Kimberly Clausing, an expert on corporate profit shifting. "I admire the fact that he's willing to look at these harder questions." Saez says Zucman's "defining characteristic is that he's not moored to the traditional economic model." In the end, Saez adds, "that gives him tremendous power to make progress."

Economists argue over the timing and size of the U.S.'s inequality surge, but few deny the broader trend. We live in an age in which the richest man in modern history is reduced by divorce to merely the richest man alive and in which even the most generous billionaires can't give away money faster than they're bringing it in. The debate now raging is over how inequality deepened to this extent and what, if anything, to do about it.

On one hand are those who argue that great wealth is somehow natural, the result of technology, globalization, and pro-growth policies bestowing outsize rewards on the smartest and most resourceful. Returning to postwar marginal tax rates of 70% or higher, they say, would discourage innovation and hurt the economy. Ken Griffin, a hedge fund manager who made news in January by dropping $360 million on two abodes in London and New York, told Bloomberg News the following month that such tax hikes would represent attempts to "destroy the wealth creators of our society."

Others see these types of proposals as necessary to address the economic and political distortions that lead to wealth stratification. In her campaign announcement, Warren described President Trump as "the latest and most extreme symptom of what's gone wrong in America, a product of a rigged system that props up the rich and the powerful and kicks dirt on everyone else." Even some billionaires have gotten the religion. In April, Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, the world's largest hedge fund, called the widening U.S. economic divide a "national emergency" that, left unaddressed, will lead to "some form of revolution."

Zucman sees ominous signs in the rise of the far right—the threat that has preoccupied him since he was a teenager on the streets of Paris. Inequality, he says, paves the way for demagogues. The causes he's identified for the widening gap in the U.S. are a host of policy changes that started in the 1980s: lower taxes on the wealthy, weaker labor protections, lax antitrust enforcement, runaway education and health-care costs, and a stagnant minimum wage. America's skyrocketing wealth disparity, he says, reflects that "it's also the country where the policy changes have been the most extreme."

When Reagan cut the top marginal tax rate from 70% to 28% across eight years, and later, when Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush slashed tax rates for investors, they were doing so on the advice of economists. The prevailing belief, backed by theoretical models, was that lower taxes on the wealthy would stimulate more investment and thus more economic growth. The real world hasn't been kind to those theories.

Since the era of liberalization and globalization began about 40 years ago, America's economic growth has been markedly slower than it was the four decades prior. And though Zucman acknowledges that gross domestic product has risen faster in the U.S. than in other developed countries, he points out that the same is true of population. Measured in GDP per person or national income per adult, U.S. growth since 1980 is hard to distinguish from the pace in France, Germany, or Japan. Meanwhile, the typical worker was better off abroad. From 1980 to 2014, for example, incomes for the poorest half of Americans barely budged, while the poorest half in France saw a 31% increase. "The pie has not become bigger" in the U.S., Zucman says. "It's just that a bigger slice is going to the top."

Share of Wealth Within Select Countries, 2014

Data: World Inequality Database

The actual effect of lower taxes on the rich, he argues, isn't to stimulate the economy but to further enrich the rich and further incentivize greed. In his analysis, when the wealthy get tax breaks, they focus less on reinvesting in businesses and more on hiring lobbyists, making campaign donations, and pursuing acquisitions that eliminate competitors. Chief executive officers, for their part, gain additional motivation to boost their own pay. "Once you've created a successful business and the wealth is established and you own billions of dollars, then what these people spend their time doing is trying to defend that position," Zucman says.

Even some inequality researchers question his and Saez's proposal to restore postwar tax rates, though. Columbia University's Wojciech Kopczuk, who once studied estate tax data with Saez, says citing inequality as grounds for such changes sounds "like an ex post facto justification of things you would want to do anyway." The consequences of these policies, he notes, might include causing truly innovative entrepreneurs to lose control of their businesses. "Once you start naming these problems, you realize there are other solutions," he says. He suggests the U.S. would be better off aggressively enforcing antitrust laws or tightening campaign finance laws.

Zucman says the response to inequality must be aggressive because wealth is self-reinforcing. The rich can always earn more, save more, and then spend more than everyone else to get their way. He considers Trump's 2017 tax law—which slashed rates on corporations, created a new deduction for business owners, and made the estate tax even easier to avoid—to be a textbook example. After decades of rising inequality and policies favorable to the top 0.1%, the U.S. delivered the rich a boatload of new goodies. "It's hard not to interpret that as a form of political capture," Zucman says.

"The wealth is not visible in plain sight—it's visible in the data"

Inside a Berkeley lecture hall in February, Zucman stepped 100 or so undergraduates through a few centuries of inequality, from slavery and the Industrial Revolution to the internet and climate change. Dressed in black, bearded, and pacing the front of the lecture hall, he approvingly quoted the classical 18th century economist Adam Smith on trade's powerful impact on growth. This, he pointed out, is how countries such as China and South Korea pulled themselves up from poverty—an example of how at least one form of inequality, between nations, was addressed.

For someone whose policy prescriptions are occasionally cast as radical, Zucman's demeanor and rhetoric tend to the mild. He peppered the class with questions, urging reluctant undergraduates to offer their own explanations for economic history and stumbling briefly, despite his excellent English, over a student's use of the expression "two heads are better than one." He warned everyone that if the trends continue, their future could resemble the distant past.

In the slow-growing, hierarchical societies leading up to the 20th century, he said, the most important factor determining your economic prospects was the class into which you were born; from Italy to India, the poor stayed poor and the rich stayed rich. By the mid-20th century, though, the most crucial factor was the country of your birth. In the U.S. and Western Europe, rags-to-riches stories became common, if not routine. Maybe, Zucman warned, the 20th century was an egalitarian anomaly and inherited wealth would again dominate. The question, he said, is "how to have a meritocratic society when so much of wealth comes from the past."

That day he also met with Saez to talk about a website the two were building. It had been a few weeks since Warren unveiled her wealth tax, and the men were creating a customizable tool to show the math underlying her proposal and let others formulate plans of their own. Saez mostly ran the meeting, but Zucman offered one suggestion: Give users the option of setting the rates as high as possible. Saez smiled and agreed.

Polls suggest that voters like Warren's wealth tax, which would levy 2% on fortunes greater than $50 million and 3% on those higher than $1 billion. But the idea of taxing wealth, rather than income, alarms some policy experts and more than a few billionaires. Speaking on NPR, Howard Schultz, former Starbucks Corp. CEO and a potential independent presidential candidate, called Warren's proposal "ridiculous," adding, "You can't just attack these things in a punitive way."

Others question how the government would value the assets of the rich, including their private businesses. Ideas such as Warren's "work very poorly in practice," Columbia's Kopczuk says. "There is a reason why many countries get rid of wealth taxes." At least 15 European countries have tried them; all but four have repealed them, most recently France.

Zucman responds that most European wealth taxes are poorly designed and that the practical issues can be resolved. For starters, such taxes must be created without loopholes allowing money to be stashed in trusts or offshore accounts. Then, with the legal regime in place, data technology could help tax collectors such as the IRS track and value wealth. A worldwide financial registry—or, failing that, the collection agencies—could require the rich to report all their transactions, exposing their holdings to scrutiny while providing the data needed to valuate similar assets. "Too many people just start from the assumption that it's impossible," he says.

The scope of the possible started widening after the financial crisis, as the U.S. and then the European Union moved to crack down on offshore shelters. The Panama Papers, a leak of millions of documents from a Central American law firm, pushed policymakers further. "We've won the argument," says Alex Cobham, CEO of Tax Justice Network, an independent international advocacy group. "More or less everyone thinks banking secrecy should be finished."

In recent months, Zucman has devoted a great deal of energy to the question of how multinational corporations avoid taxes. He's produced papers and policy briefs showing that U.S. multinationals shift almost half of their overseas profits to five havens—Ireland, the Netherlands, Singapore, Switzerland, and the Greater Caribbean, which includes Bermuda. "That is a huge problem for the sustainability of globalization," he says. Countries and territories are engaged in a race to the bottom, Zucman argues, offering ever-lower corporate rates in the fear that companies will shift their profits elsewhere. He proposes to "annihilate" such competition by apportioning profits based on where sales were made.

These ideas might be nonstarters today, but Zucman professes to take the long view. Remember, he points out, that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the income tax unconstitutional in 1895; it took a constitutional amendment to legalize it in 1913. "There's a lot of policy innovation ahead of us," he says.

When Zucman and Saez's site, wealthtaxsimulator.org, went live in March, it sparked some of that hoped-for innovation. One proposal, posted on Twitter by Adam Bonica, a political science professor at Stanford, was for a 100% tax on wealth beyond $500 million. He based it on what he called "Beyoncé's rule," which he explains as, "Think of the most talented and hardest-working person you know, and think about how much money they have and how much money they deserve." Queen Bey, he tweeted, has an estimated net worth in the neighborhood of half a billion dollars. "Let's have Howard Schultz explain to us why he should be worth more than Beyoncé."

Harpers Ferry, WV

Dear Folks,

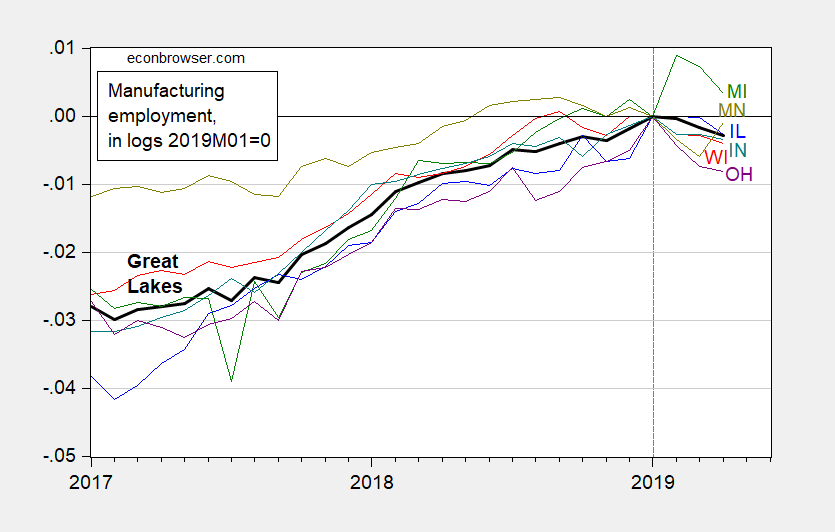

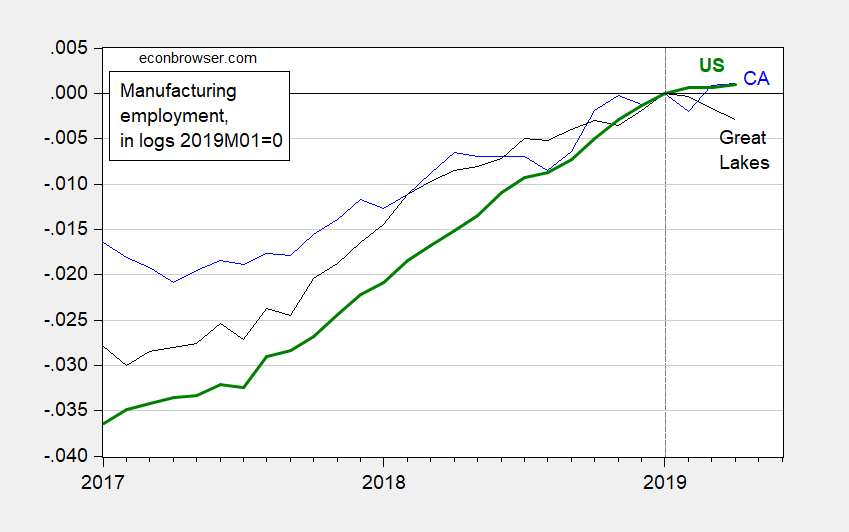

A brief response to PGL and others. Lots of people read more than newspapers. If this administration is favoring Russia, good by good, (and yes, I am not discriminating between production by a firm headquartered here which produces in Germany and a firm which produces here, because they can be moved as foreign direct investment, which is already happening to some extent), it is also favoring other states besides the Midwest. OFII can be disputed about FDI figures, but see

https://siteselection.com/issues/2019/mar/south-carolina-the-souths-magnet-for-foreign-direct-investment.cfm

and in particular:

"In fact, international companies operating in states like Florida, Iowa, Michigan, North Carolina and Ohio have grown their manufacturing workforce by more than 20 percent over that period."

and

"10 States with the Fastest FDI Employment Growth Rate Over the Past Five Years: Utah (45.7 percent), Florida (43.8 percent), Tennessee (41.3 percent), Oregon (41.0 percent), Michigan (39.7 percent), Kentucky (37.1 percent), Mississippi (36.3 percent), South Dakota (36.0 percent), Missouri (35.0 percent) and Arizona (34.8 percent). The national average is 24.4 percent.

Leading American Manufacturing: International companies were responsible for 62 percent of U.S. manufacturing job growth, contributing 377,200 of the 606,000 net manufacturing job gains made from 2011 to 2016 (latest available data). The 10 states with the fastest FDI manufacturing growth rate include: Rhode Island, South Dakota, Oregon, Michigan, Kentucky, Nebraska, Iowa, Tennessee, Utah and Minnesota."

Are they analyzing the latest data? No. And you can look at the same figures and see employment growth over 2008-2016 and see Ohio and Michigan, depending on what metric you use, as above. But the primary states where manufacturing growth is taking place, with exceptions, are not in the Midwest.