The Left's Choice

In the face of resurgent right-wing populism, the left's relative weakness partly reflects the decline of unions and organized labor groups, which have historically formed the backbone of leftist and socialist movements. But four decades of ideological abdication has also played an important role.

17Add to Bookmarks

PreviousNext

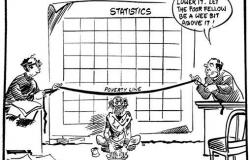

The left and progressive groups have been largely missing in action. The left's relative weakness partly reflects the decline of unions and organized labor groups, which have historically formed the backbone of leftist and socialist movements. But ideological abdication has also played an important role. As parties of the left became more dependent on educated elites instead of the working class, their policy ideas aligned more closely with financial and corporate interests.

The remedies on offer from mainstream leftist parties remained correspondingly limited: more spending on education, improved social-welfare policies, a bit more progressivity in taxation, and little else. The left's program was more about sugarcoating the prevailing system than addressing the fundamental sources of economic, social, and political inequities.

There is now growing recognition that tax-and-transfer policies can go only so far. While there is much room for improving social insurance and tax regimes, especially in the US, deeper reforms are needed to help level playing fields in favor of ordinary workers and families across a broad range of domains. That means focusing on product, labor, and financial markets, on technology policies, and on the rules of the political game.

Inclusive prosperity cannot be achieved by simply redistributing income from the rich to the poor, or from the most productive parts of the economy to less productive sectors. It requires less-skilled workers, smaller firms, and lagging regions to be more fully integrated with the most advanced parts of the economy.

In other words, we must start with productive re-integration of the domestic economy. Large and productive firms have a critical role to play here. They must recognize that their success depends on the public goods that their national and sub-national governments supply – everything from law and order and intellectual property rules to infrastructure and public investment in skills and research and development. In exchange, they must invest in their local communities, suppliers, and workforce – not as corporate social responsibility, but as a mainline activity.

In an earlier age, governments engaged in agricultural extension activities to spread new techniques to small farmers. There is a similar role today for what Timothy Bartik of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research calls "manufacturing extension services," though the ideas apply to productive services as well. Governments that collaborate with businesses to encourage the dissemination of frontier technologies and management techniques to the rest of the economy can avail themselves of a well-established repertoire of such initiatives.

A second area of public action concerns the direction of technological change. New technologies such as automation and artificial intelligence (AI) have typically been labor-replacing, adversely affecting low-skill workers in particular. But this need not be the case in the future. Instead of policies (such as capital subsidies) that inadvertently promote labor-replacing technologies, governments could promote technologies that augment labor-market opportunities for less-skilled workers.

The late economist Tony Atkinson, in his magisterial book Inequality, questioned the wisdom of governments supporting the development of autonomous vehicles, without due consideration for the effects on taxi and truck drivers. More recently, the economists Daron Acemoğlu, Anton Korinek, and Pascual Restrepo have written about how AI can be deployed in new ways to increase labor demand, for example by allowing ordinary workers to engage in activities that were previously out of reach for them. But moving in this direction will require a conscious effort by governments to review their innovation policies and to put the appropriate private-sector incentives in place.

Labor markets, too, need rebalancing. The weakening of unions and protections for workers has eroded traditional sources of countervailing power. Recent research has shown that firms retain significant bargaining leverage over employees, depressing wages and working conditions. Reversing these trends will require a range of pro-labor policies, including the promotion of unionization, higher minimum wages, and adequate regulatory standards for workers in the "gig economy."

Finance is yet another area requiring significant surgery. Most advanced economies' financial sectors remain bloated. They pose continuing risks to economic stability without providing compensating benefits in terms of increased investment in productive activities. As Stanford's Anat Admati and others have long argued, banks require, at a minimum, higher capital requirements and tighter regulatory scrutiny. The fact that financial institutions have escaped relatively unscathed from the crisis of 2008-2009 speaks volumes about their political power.

As the failures of financial regulation suggest, important as such economic reforms are, they need to be complemented with measures that remedy the asymmetry of political access. In the US, holding elections on workdays, rather than weekends or holidays – together with restrictive registration rules, gerrymandering, and myriad other electoral rules – places ordinary workers at a significant disadvantage. This is on top of campaign finance rules that have enabled corporations and society's wealthiest members to exert inordinate influence on legislation.

The Democratic Party will face a critical test in the next US presidential election, less than two years away. In the meantime, it has a choice to make. Will it remain the party of merely adding sweeteners to an unjust economic system? Or does it have the courage to address unfair inequality by attacking it at its roots?

The Euro Turns 20

Jan 7, 2019 DANIEL GROS

Why Is Immigration Different from Trade?

Jan 11, 2019 AMAR BHIDÉ

DANI RODRIK

Writing for PS since 1998

152 Commentaries

Subscribe

Dani Rodrik is Professor of International Political Economy at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government. He is the author of The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy, Economics Rules: The Rights and Wrongs of the Dismal Science, and, most recently, Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy.

Harpers Ferry, WV