http://understandingsociety.blogspot.com/2019/01/the-research-university.html

Jason Owen-Smith's recent Research Universities and the Public Good: Discovery for an Uncertain Future is a very welcome and insightful contribution to better understanding this topic. Owen-Smith is a sociology professor at the University of Michigan (itself a major research university with over 1.5 billion dollars in annual research funding), and he brings to his task some of the most insightful ideas currently transforming the field of organizational studies.

Owen-Smith analyzes research universities (RU) in terms of three fundamental ideas. RUs serves as source, anchor, and hub for the generation of innovations and new ideas in a vast range of fields, from the humanities to basic science to engineering and medicine. And he believes that this triple function makes research universities virtually unique among American (or global) knowledge-producing organizations, including corporate and government laboratories (33).

The idea of the university as a source is fairly obvious: it is the idea that universities create and disseminate new knowledge in a very wide range of fields. Sometimes that knowledge is of interest to a hundred people worldwide; and sometimes it results in the creation of genuinely transformative technologies and methods. The idea of the university as "anchor" refers largely to the stability that research universities offer the knowledge enterprise. Another aspect of the idea of the university as an anchor is the fact that it helps to create a public infrastructure that encourages other kinds of innovation in the region that it serves -- much as an anchor tenant helps to bring potential customers to smaller stores in a shopping mall. Unlike other knowledge-centered organizations like private research labs or federal laboratories, universities have a diverse portfolio of activity that confers a very high level of stability over time. This is a large asset for the country as a whole. It is also frequently an asset for the city or region in which it is located.

The idea of the university as a hub is perhaps the most innovative perspective offered here. The idea of a hub is a network concept. A hub is a node that links individuals and centers to each other in ways that transcend local organizational charts. And the power of a hub, and the networks that it joins, is that it facilitates the exchange of information and ideas and creates the possibility of new forms of cooperation and collaboration. Here the idea is that a research university is a place where researchers form working relationships, both on campus and in national networks of affiliation. And the density and configuration of these relationships serve to facilitate communication and diffusion of new ideas and approaches to a given problem, with the result that progress is more rapid. O-S makes use of Peter Galison's treatment of the simultaneous discovery of the relativity of time measurement by Einstein and Poincaré in Einstein's Clocks and Poincaré's Maps: Empires of Time. Galison shows that Einstein and Poincaré were both involved in extensive intellectual networks that were quite relevant to their discoveries; but that their innovations had substantially different effects because of differences in those networks. Owen-Smith believes that these differences are very relevant in the workings of modern RUs in the United States as well. (See also Galison's Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics.)

Radical discoveries like the theory of special relativity are exceptionally rare, but the conditions that gave rise to them should also enable less radical insights. Imagining universities as organizational scaffolds for a complex collaboration networks and focal point where flows of ideas, people, and problems come together offers a systematic way to assess the potential for innovation and novelty as well as for multiple discoveries. (p. 15)

Treating a complex and interdependent social process that occurs across relatively long time scales as if it had certain needs, short time frames, and clear returns is not just incorrect, it's destructive. The kinds of simple rules I suggested earlier represent what organizational theorist James March called "superstitious learning." They were akin to arguing that because many successful Silicon Valley firms were founded in garages, economic growth is a simple matter of building more garages. (25)Rather, O-S demonstrates in the case of the development of the key discoveries that led to the establishment of Google, the pathway was long, complex, and heavily dependent on social networks of scientists, funders, entrepreneurs, graduate students, and federal agencies.

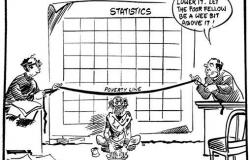

A key observation in O-S's narrative at numerous points is the futility -- perhaps even harmfulness -- of attempting to harness university research to specific, quantifiable economic or political goals. The idea of selecting university research and teaching programs on the basis of their ROI relative to economic goals is, according to O-S, deeply futile. The extended example he offers of the research that led to the establishment of Google as a company and a search engine illustrates this point very compellingly: much of the foundational research that made the search algorithms possible had the look of entirely non-pragmatic or utilitarian knowledge production at the time it was funded (chapter 1). (The development of the smart phone has a similar history; 63.) Philosophy, art history, and social theory can be as important to the overall success of the research enterprise as more intentionally directed areas of research (electrical engineering, genetic research, autonomous vehicle design). His discussion of Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker's effort to revise the mission statement of the University of Wisconsin is exemplary (45 ff.).

Contra Governor Walker, the value of the university is found not in its ability to respond to immediate needs but in an expectation that joining systematic inquiry and education will result in people and ideas that reach beyond local, sometimes parochial, concerns. (46-47)Also interesting is O-S's discussion of the functionality of the extreme decentralization that is typical of most large research universities. In general O-S regards this decentralization as a positive thing, leading to greater independence for researchers and research teams and permitting higher levels of innovation and productive collaboration. In fact, O-S appears to believe that decentralization is a critical factor in the success of the research university as source, anchor, and hub in the creation of new knowledge.

The competition and collaboration enabled by decentralized organization, the pluralism and tension created when missions and fields collide, and the complex networks that emerge from knowledge work make universities sources by enabling them to produce new things on an ongoing basis. Their institutional and physical stability prevents them from succumbing to either internal strife or the kinds of 'creative destruction' that economist Joseph Schumpeter took to be a fundamental result of innovation under capitalism. (61)O-S's discussion of the micro-processes of discovery is particularly interesting (chapter 3). He makes a sustained attempt to dissect the interactive, networked ways in which multiple problems, methods, and perspectives occasionally come together to solve an important problem or develop a novel idea or technology. In O'S's telling of the story, the existence of intellectual and scientific networks is crucial to the fecundity of these processes in and around research universities.

This is an important book and one that merits close reading. Nothing could be more critical to our future than the steady discovery of new ideas and solutions. Research universities have shown themselves to be uniquely powerful engines for discovery and dissemination of new knowledge. But the rapid decline of public appreciation of universities presents a serious risk to the continued vitality of the university-based knowledge sector. The most important contribution O-S has made here, in my reading, is the detailed work he has done to give exposition to the "micro-processes" of the research university -- the collaborations, the networks, the unexpected contiguities of problems, and the high level of decentralization that American research universities embody. As O-S documents, these processes are difficult to present to the public in a compelling way, and the vitality of the research university itself is vulnerable to destructive interference in the current political environment. Providing a clear, well-documented account of how research universities work is a major and valuable contribution.

-- via my feedly newsfeed