An intro to how insurance companies plan to cover catastrophe's---its going to take more money

http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2018/11/catastrophe-bonds-primer.html

Catastrophe Bonds: A Primer

Most bonds are a way for corporations and government to borrow money. A catastrophe bond is different. It's effectively a way for an insurance firm to re-insure some of the extreme risks it faces.

Andy Polacek offers a nice overview in "Catastrophe Bonds: A Primer and Retrospective," a recent

Chicago Fed Letter (2018, No. 405).Andy Polacek offers a nice overview in "Catastrophe Bonds: A Primer and Retrospective," a recent

Polacek offers a nice concrete example of how a CAT bond works. The American Family Mutual Insurance Company wanted to be reinsured if it experienced very high losses due to severe thunderstorms and tornadoes in the United States. Thus, in November 2010 it set up a "special purpose vehicle" called Mariah Re Ltd. to issue a CAT bond.

It worked like this. Investors in the CAT bond put up $100 million. That money was immediately invested in US Treasury securities. In addition, American Family Mutual Insurance Company agreed to pay the investors an additional return of 6.25% per year, over a three-year period. If there were no excessive losses from thunderstorms during those three years, the CAT bond would end, and the $100 million would be refunded to the original investors.

However, every CAT bond has built into it an "attachment point," which specifies when a certain large-scale event has occurred. It might refer to an earthquake of a certain size, or to a certain kind of storm causing at least a certain magnitude of losses. In the case of American Family Mutual Insurance Company and Mariah Re, the "attachment point" occurred "if estimated losses to the P&C insurance industry from severe thunderstorms and tornadoes across the U.S. exceeded $825 million ... After the $825 million attachment point was reached, AFMI would receive $1 in compensation for every $1 of additional covered losses up to the $100 million limit." A third party is designated in advance to decide if the "attachment point" has been reached: in this case, the third party was a company called AIR Worldwide.

This example helps to clarify the risk-sharing properties of a CAT bond. For the insurance company, issuing a CAT bond is a way of purchasing re-insurance against extreme losses. But it has some advantages over purchasing reinsurance. Because the money is sitting in an account, there is no danger that the reinsurance company might be unable to pay. Also, a CAT bond can be set up to cover a period of several years, while a reinsurance purchase is typically for one year. Finally, because lots of investors like pension funds, mutual funds, and hedge funds can buy CAT bonds, the pool of funds available for reinsurance becomes a lot larger than the available capital of reinsurance companies taken alone

For investors, a CAT bond offers a rate of return with a degree of risk, with the nice property that the occurrence of extreme insurance events is typically not much correlated with other risks in financial markets. In this particular case of American Family Mutual Insurance Company and Mariah Re, the US experienced a huge number of costly and deadly tornadoes in 2011, leading to insured losses of $954 million. This total was more than $100 million above the attachment point of $825 million, so that investors in this CAT bond lost all of the $100 million they had invested. But over time, the actual returns from investing in CAT bonds have been attractive.

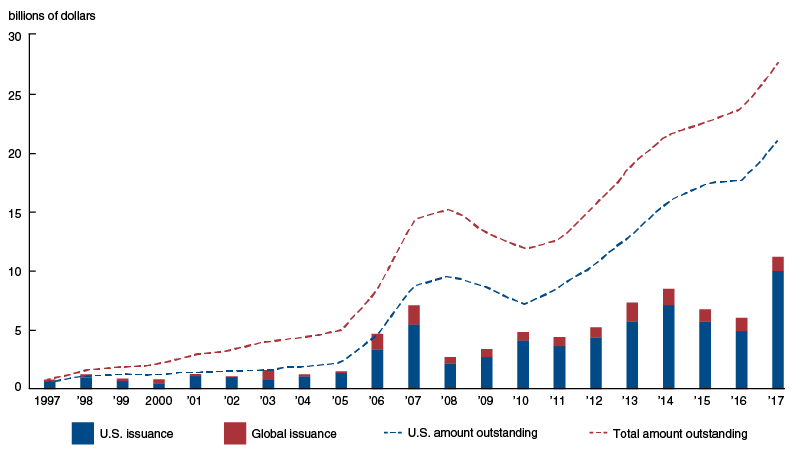

This figure shows the growth in total issuance of catastrophe bonds over time, now at about $25 billion worldwide.

One of the most interesting uses of CAT bonds is not by insurance or reinsurance companies, but by governments. Payouts from these CAT bonds often triggered by measures of the strength of the covered catastrophe—such as an earthquake's magnitude or a hurricane's wind speed and barometric pressure. As a result, it is typically quite clear when a trigger has been exceeded, and the fund to cover the catastrophe can be released very quickly, when they are needed. In the US, the California Earthquake Authority (CEA) and the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund (FHCF) issue catastrophe bonds. "The Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF)—developed with the assistance of the World Bank—has used CAT bonds ... After Hurricane Matthew struck the Caribbean in the fall of 2016, the CCRIF paid out a little over $20 million to Haiti and almost $1 million to Barbados within 14 days after the triggering event."

A common concern about any new financial instrument is that it will work until investors take substantial and losses, and then it may fade away. Thus, it is a good sign for the fundamental health of catastrophe bonds as a useful financial innovation that even after experiencing very large losses for investors in 2017, it kept growing in 2018. Polacek writes:

"In the first half of 2018, the CAT bond market saw strong growth even after unequivocally the worst period for CAT bond investors in the market's 20-year history. Led primarily by losses from Hurricanes Irma, Harvey, and Maria, 19 separate CAT bond tranches were triggered in the third quarter of 2017, leaving as much as $1.4 billion in outstanding issuance vulnerable to losses (the actual loss amount is not yet known given that many insurance claims still need to be resolved). Despite the historic level of losses at the end of 2017, new CAT bond issuance in the first half of 2018 reached $9.4 billion, rivaling 2017's record start.20 Currently, the insurance industry is working to improve CAT bond modeling to cover new types of risk—such as cyberattack and terror risks. So, it appears that the uses of CAT bonds will continue to grow, offering issuers new avenues to transfer a variety of risks."For a previous post on CAT bonds, see "The Allure of Catastrophe Bonds"(August 25, 2016).

-- via my feedly newsfeed