The election of the left populist Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico is a historic breakthrough for progressives there. It could also offer progressives in the United States a path out of their own political stalemate on immigration and trade.

In his third run for president, 64-year-old "AMLO" broke open the piñata of Mexican politics that had been tightly sealed by neoliberal oligarchs since the early 1980s. He won 31 of the 32 Mexican states, taking 53 percent of the total vote. His coalition, led by the political party he organized just four years ago, swept to control in both houses of the Mexican Congress.

As in his past campaigns, López Obrador was demonized in most of the media as a Latin American caudillo like Hugo Chavez, who would bring Venezuela-type chaos, or the Mexican version of the despised Donald Trump.

The comparisons are pure propaganda; López Obrador has no connection with the military, has spent his life in democratic politics, and could not be less like Trump. From a family of small shopkeepers, he began his political career by defending the land rights of the indigenous poor in his native Tabasco. Since then, he has been a relentless critic of what he calls the "mafioso" Mexican elite, whose greed has spread corruption and tolerated violence throughout the country. He has a modest lifestyle, driving a five-year-old car, flying coach, and promising to cut the president's salary and sell the presidential plane.

Unlike Trump, he is also an astute and pragmatic politician. As mayor of Mexico City between 2000 and 2005, he ran a competent and innovative government—launching programs that ranged from helping the poor and elderly to building elevated highways to ease the congestion that was choking local commerce. He left office with an 85 percent approval rating.

Within days of his election as president, he met with business leaders who had bitterly opposed him, plunged into the practical issues of the upcoming transfer of power in December, and appointed a cabinet of people with recognized experience and expertise—a majority of whom are women.

Yet, as different as they are, López Obrador and Trump are products of a similar historical context. They represent, respectively, left- and right-wing populist/nationalist responses to the economic insecurity and social disruption of corporate-driven globalization.

The similarities end there. Trump is a monstrous parody of capitalist imperialism—bullying, greedy, and unstable—who brazenly uses the presidency to promote his personal business deals in dozens of countries. He plays to his political base with xenophobic rants, while personally profiting from cheap immigrant labor on his worksites and at his homes.

By contrast, López Obrador's nationalism is rooted in a long struggle for democratic control over Mexico's economic and social development.

After 20 years of civil conflict following the Mexican Revolution of 1910, the country's exhausted warring factions established a system of broadly representative one-party rule. The system was autocratic, inward-looking, mildly socialist, and consciously distanced from the United States, which had dominated—and dismembered—Mexico over the previous century. The system brought 50 years of peace, steady economic growth, and decreasing inequality to the nation.

But in the early 1980s, the international energy-price bubble burst, plunging oil-exporting Mexico into an economic crisis. Infected by the market-fundamentalism of the Reagan-Thatcher era, a new generation of politicians allied with U.S. business interests opened up Mexico to the global economy. Their instrument was the North American Free Trade Agreement with the United States and Canada, which in turn became the model for the global deregulation of trade and investment that swept the world over the next two decades.

Not surprisingly, NAFTA failed to deliver on the promise of its backers that it would reduce Mexican immigration in the United States. President Clinton also argued that allowing U.S. companies to produce in Mexico would prevent them from going to China. NAFTA, he claimed, would create a growing middle-class job market—and middle-class consumers for American goods—in Mexico. In a similar vein, then-Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari asked Americans, "Do you want our tomatoes or our tomato pickers?"

But these promises turned out to be so much political bait and switch. Instead of a North American strategy for global competition, NAFTA turned out to be a Wall Street strategy to undercut the bargaining position of labor in all three countries. A half-dozen years after NAFTA took effect, Clinton opened up the United States to goods from China in exchange for opening up China to American investors. The privileged U.S. access promised to Mexico was undercut by even cheaper Chinese labor. Many Mexicans—echoing the bitterness of downsized U.S. industrial workers—will tell you that Clinton stabbed them in the back.

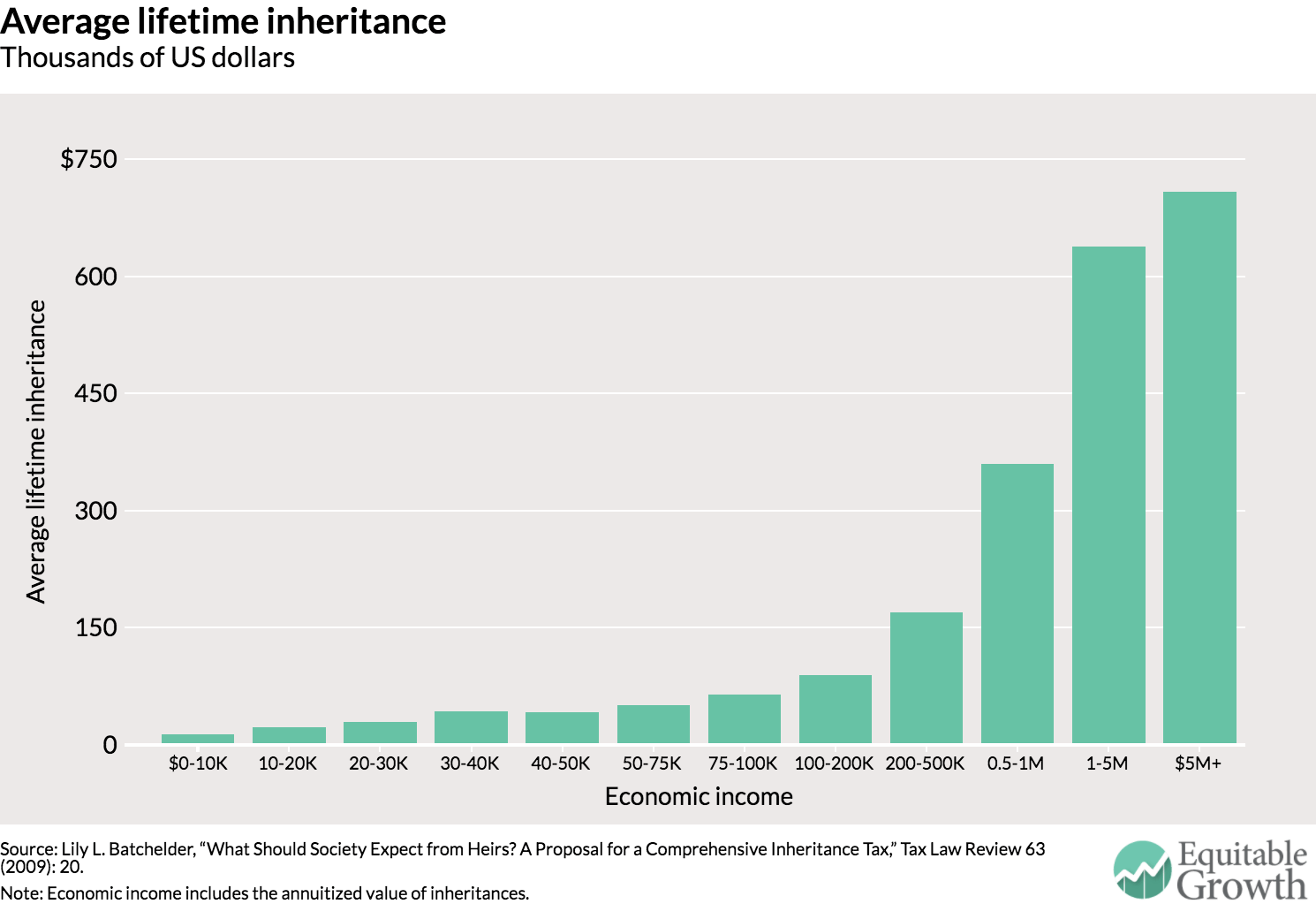

Compared with their experience in the previous era, Mexicans since NAFTA have seen slower growth, widening inequality, and less personal safety. As writer Jorge Castañeda Gutman, who later became foreign minister, acknowledged at the time it was adopted, NAFTA was "an agreement for the rich and powerful in the United States, Mexico, and Canada, an agreement effectively excluding ordinary people in all three societies."

López Obrador on October 17, 2018

Deregulating the flow of money and goods across the border also turned what had been a modest, illegal business smuggling marijuana into the United States into a huge criminal industry that now encompasses trans-shipping cocaine and heroin from South America and synthetic drugs from the Far East. Narco-traffickers expanded into extortion, robbery, and kidnapping. Drug money infiltrated the courts, the police, and the military. Only 7 percent of the country's crimes are reported, chiefly because of fear of the police. Of those reported, less than 5 percent result in convictions. During the recent elections, at least 145 candidates and political activists were assassinated.

In 2008, the Pentagon started providing aid to the Mexican military to take over the leading role in combating the cartels. But the military is untrained for police work, unaccountable to civilian authority, and itself laced with narco-corruption. Human rights violations have escalated. Last spring, the Mexican government was caught using surveillance systems paid for by the United States to spy on its political opponents. By any measure, the U.S. intervention has been a complete failure; in 2017, the murder rate in Mexico reached its highest level since the government started keeping records 20 years ago.

WHILE ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION to the United States tripled between 1990 and 2013, a weak U.S. recovery from the crash of 2008 combined with Obama's tougher border policies have since reduced the flow from Mexico. Trump's brutal tactics have taken a further toll. Yet the flow continues; in the first seven months of 2018, the number of undocumented people arrested or turned back at the southern border rose by 140,000 over the same period a year ago. A growing share has come from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, where the combination of criminal violence and chronic poverty is even greater than in Mexico.

Lost in this debate is the uncomfortable reality that Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador have long been de facto colonies of U.S. corporate and military interests. For well over a century, we have intervened in the region to support the reactionary business oligarchs and generals who have brutally suppressed both development and democracy.

This is not just ancient history. In 2009, when the elected president of Honduras, himself a member of the oligarchy, outraged the Honduran establishment by attempting a few mild education and labor market reforms, he was kidnapped by U.S.-trained armed forces, taken to a U.S. base, and shipped out of the country. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton supported the coup, following up with increased aid to the Honduran military and the corrupt government it protects. When protesters demonstrated against this year's rigged election, the military police fired live ammunition at them, killing at least 20 of the demonstrators.

The dirty little secret of migration across our southern border is that it has benefited elites on both sides. The Mexican and Central American oligarchs get to send their most ambitious and energetic—and therefore the most frustrated and politically dangerous—working people out of the country. The U.S. business class gets a large supply of ambitious, energetic, cheap labor. And as the recent numbers suggest, wall or no wall, desperate people will keep finding a way in.

AS IF THE PROBLEMS OF inequality, violence, and corruption on López Obrador's plate when he takes office were not enough, there awaits the foul-mouthed Donald Trump, still demanding that Mexico pay for his border wall, which no Mexican politician could possibly do.

But neither can any Mexican leader avoid dealing with Trump. López Obrador, like his progressive counterparts in Canada, originally opposed NAFTA. Leftists in both countries feared that greater integration with the United States would weaken their already fragile national independence. As the humiliating submission of their leaders to Trump's arrogant demand for a renegotiation of NAFTA showed, they were right.

After 24 years of integration under NAFTA, the economies of both Mexico and Canada are much more dependent on their larger neighbor. Mexico especially relies on the U.S. for imports of basic foods and gasoline, and it sells 80 percent of its exports in the United States. López Obrador is fully aware that tearing up the treaty now would plunge Mexico into a depression from which it would take years to recover, and doom his plans for turning the country toward a social democratic future.

López Obrador has been arguing that the central issue is not how the United States treats undocumented Mexican immigrants, but the maldistribution of income and wealth that drives them out of Mexico. The priority should not be making it easier for Mexicans to leave their country, he says, but making it possible for them to stay.

To do this, he has laid out an ambitious plan of economic development along social democratic lines, terming policies of the past a failure. After his election, he declared that neoliberalism was finished in Mexico. His plan includes:

- Increasing public social spending, particularly in education and pensions for the destitute elderly,

- Raising private incomes with higher minimum wages and reform of corrupt labor unions,

- Job creating investments—especially in the impoverished south—in water, transportation, energy, and the targeted expansion of new industries, including exporting to the world's rapidly legalizing marijuana markets.

At the same time, he must make visible progress against the widespread criminal violence and official corruption. As a first step, he wants to de-militarize the war on drugs, sending the army back to its barracks while reforming and professionalizing the civilian police.

This is a huge task, and he will be opposed by powerful international, as well as national, interests—including Wall Street investors, the Pentagon and its contractors who are close to the Mexican military, and the right-wing ideologues both in Mexico and in the U.S. administration and Congress. To have a chance of pulling it off, López Obrador needs time and political space—and minimal interference from the U.S. government.

His immediate need is to get the current negotiations over NAFTA out of the way, even before he takes office. Fortunately for him, the lame-duck Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto has already reached a deal with Trump, who has informed Congress that he will sign it before December 1.

Luisa María Alcalde Luján

Given Trump's unstable personality, nothing is certain. Canada has not yet joined, and even some Republicans have questioned whether Trump could base a deal with Mexico alone on his authority from Congress to renegotiate the three-nation agreement. But there is little reason to think that the spineless Republicans in Congress won't ultimately give him whatever he asks for.

Moreover, although it is hard for progressives to acknowledge that anything Trump does is positive, the proposed amendments in the deal with Mexico are an actual improvement for workers on both sides of the border. First, they weaken the rights of corporate investors to sue governments for policies that might reduce future profits. Second, they require Mexico to pass legislation ensuring workers' rights to secret ballots in union elections. Third, they mandate that the share of North American content in autos and parts that cross borders without tariffs be raised from 62.5 percent to 75 percent. Fourth, they stipulate that 45 percent of autos be produced by workers making at least $16 per hour, which if finally incorporated into NAFTA could represent a historic breakthrough for making wage levels a part of trade treaties.

The deal does not do much to strengthen enforcement of these new rules. But this could change. López Obrador's designated labor minister, Luisa María Alcalde Luján, is smart, energetic, and committed. She comes from a network of activists (including her parents) that for years has dedicated itself to cleaning up union corruption and promoting worker rights—something that has been totally absent from Mexican governments of the past.

Despite Trump's threats, there is nothing in the deal about building a wall or requiring Mexico to impede emigration to the United States. Trump, of course, is still assuring his base that, somehow, in some unspecified way, his wall will be built and Mexico will pay for it.

IN ADDITION TO dealing with the unstable and dangerous mega-power to the north, López Obrador must deal with the violence and chaos spilling over in the form of displaced immigrants from Central America. In a letter to Trump, he suggested that both Mexico and the United States work together on a new project of social and economic development for the region.

No one can expect Trump to take this seriously. But López Obrador's ideas, and the fact that he will be president of Mexico for six years, could kick-start progressives into a desperately needed rethink of America's global priorities.

It is not just Mexico that needs a new internal development path. Rising inequality, chronic trade deficits, and shrinking opportunities for the majority of Americans over the last three decades reflect a dysfunctional economy that is competing in the world by lowering wages and living standards at home.

To escape the downward spiral of low-wage competition, both the United States and Mexico need to rebuild their capacity to compete in the world on the basis of high quality and efficiency. To do this they need time—and each other. Mexico needs stable access to American investment and technology. And the United States needs Mexico and Central America—both to create a larger close-in market for American goods and to limit the forced immigration from south of the border that is a major, if not the major, subject of the nativist demagogy that breeds the reactionary politics clogging our path toward a social democratic future.

NAFTA created a continental market. U.S. trade with Canada and Mexico is almost double its trade with China. People and culture now flow across the borders. What NAFTA has lacked is a democratic politics that would make it work for the ordinary people who were left behind by the original deal.

Opposition to the original agreement in all three countries created what might have been a foundation for that politics. But after critics failed to stop it, the left embraced other concerns. In the United States, the anti-free-trade movement moved on, reaching its peak in the 1999 protests against globalization in Seattle. Today, it has been elbowed out of the trade discussion by Trump. Its internationalist human rights vision has often been misappropriated by policymakers of both parties as a justification for disastrous military interventions.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador on September 29, 2018, in Mexico City

What goes on in Mexico and Central America has much more impact on the daily lives of more Americans than events almost anyplace else. But among U.S. foreign policy networks, stretching from Congress and federal bureaucracies to academia and multinational corporations, the world south of the Rio Grande is a policy backwater. The media tell us more about who is going to jail in Turkey and China than who is murdered in El Salvador or Mexico.

THE IDEA THAT MARKET TIES among nations help create a more peaceful and just world is not wrong. What is wrong is that the neoliberal model systematically erodes the democratic governance necessary to make it work.

With the ascension of López Obrador to Mexico's presidency, the rise to influence of a new generation of progressive Democrats in their party in the United States, and the existing substantial base for progressive politics in Canada, there may be an opportunity for social democrats in all three countries to work together toward transforming NAFTA into a North American economy in which rising living standards for all who live there take priority over profit opportunities for global investors.

The first task is to strengthen cross-border ties among progressives. Within the Mexico/Central American diaspora, there is already a great deal of collaboration on immigration and environmental issues across the border. And, despite their own domestic struggles, some U.S. and Mexican labor unions have cooperated in joint organizing along the border. One recent example of trinational cooperation is the story of Napoleon Gomez, a labor leader prosecuted by the Mexican government on fake charges after he criticized the callous indifference of a powerful mining corporation to a disaster that killed 65 miners in Coahuila. The American steelworkers union helped Gomez flee the country, and Canadian trade unions gave him refuge in Canada. After the Mexican Supreme Court finally dismissed all of the charges against him, he was elected in July to the Mexican Senate as a member of López Obrador's party.

Strengthening such links among continental progressives should be a major priority for American progressives over the next few years. But they need to see progressive movements to our south not just as objects of charitable political help, but as essential partners. There is no social democratic future possible in the U.S. without a strong democratic union movement. But workers on both sides of the border need each other to succeed. Given the ongoing integration of economies, a strong union movement here is not possible without one there.

The Mexican and Central American left does not need eager U.S. progressives rushing to help them reform their countries. Far more useful is an American left inspired to press long-neglected questions about the behavior of its own. Our own left would do well to focus on why the United States maintains military bases in Central America that have nothing to do with U.S. national security, and why the United States aids the Mexican army and police with military technology that often ends up in criminal hands.

The current alliance among progressives, moderates, and establishment neoconservatives to rid our country of Donald Trump is a practical necessity. But no progressive should be lulled into thinking that the social democratic vision of the Sanders/Warren wing of the party is compatible with the bipartisan "deep state" goal of restoring America's post–World War II role as world policeman and de facto board chair of global corporate capitalism.

It's time for another strategy. And for American progressives, the place to begin is here in our own North American neighborhood.

López Obrador has suggested the next step, but he cannot do it alone.

-- via my feedly newsfeed