The "silver spoon" tax: how to strengthen wealth transfer taxation

About the author: Lily L. Batchelder is a professor of law and public policy at New York University School of Law.

Wealth transfer taxes are a critical policy tool for mitigating economic inequality, including inequality of opportunity. They are also relatively efficient. This essay summarizes why and how wealth transfer taxes should be strengthened. Reform options that our next President should consider include increasing the wealth transfer tax rate, broadening the base, repealing stepped-up basis, addressing talking points against wealth transfer taxes with little or no factual basis, and converting the estate and gift taxes into a direct tax on the recipients of large inheritances.

Why wealth transfer taxes

should be preserved and expanded

For those concerned about economic inequality, taxing wealth transfers is a critical policy tool, mitigating inequality in ways that other taxes cannot. Inheritances represent roughly 40 percent of all wealth1 and about 4 percent of annual household income.2 Bequests alone total about $500 billion per year.3

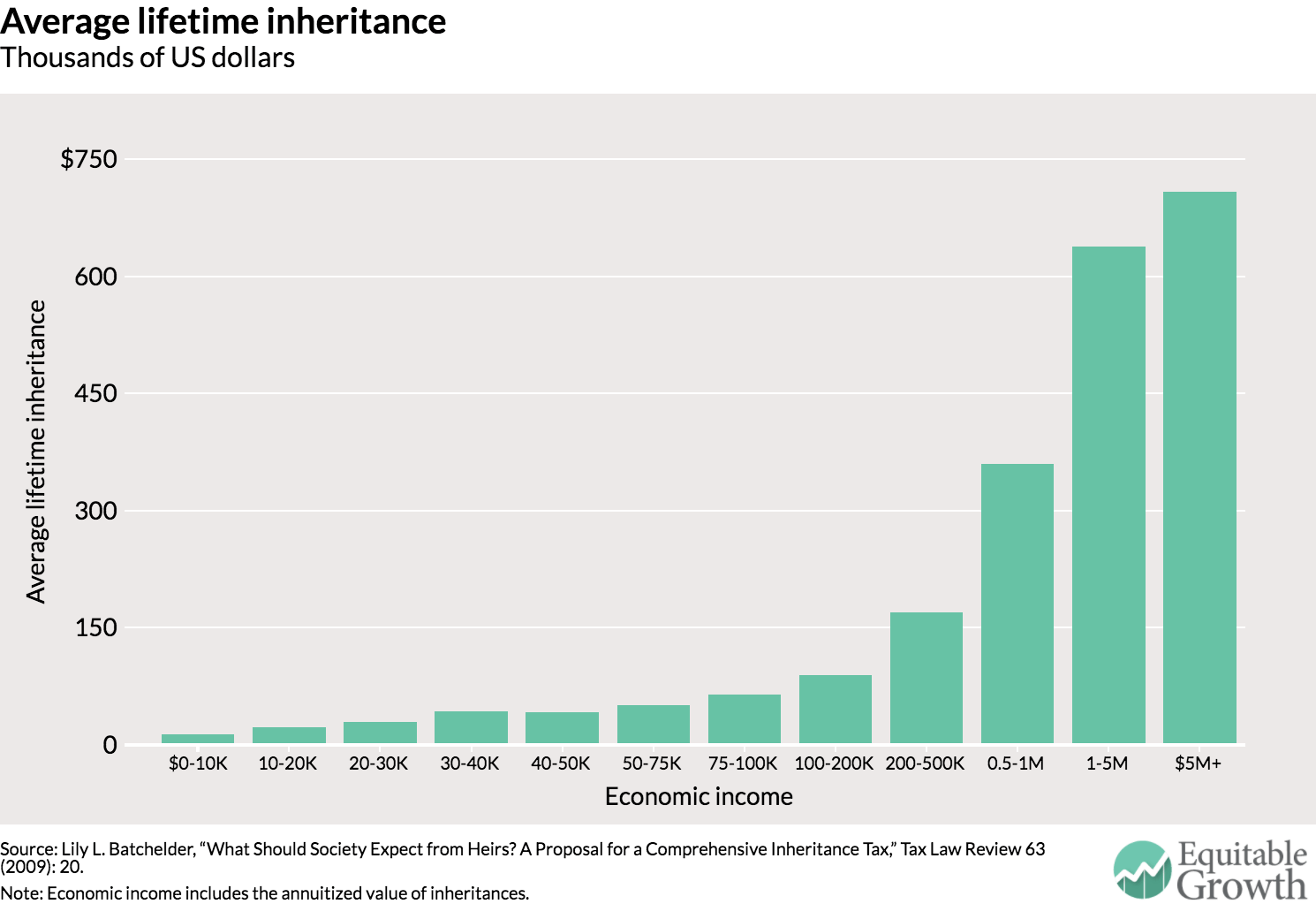

There are two types of inequality that policymakers should care about. The first is within-generation disparities in income, wealth, or other measures of economic well-being. Both income and wealth inequality are extremely high in the United States. The top 1 percent of households receives 15 percent of all income and holds 35 percent of all wealth.4Wealth transfers increase within-generation inequality on an absolute basis (See Figure 1), but not on a relative basis. This is because of what economists call regression to the mean.5 Someone who earns $100 million per year, for example, is likely to have a child whose income is slightly lower, even including the child's inheritance. Conversely, someone who earns $10,000 per year is likely to have a child whose income is slightly higher than her own.

Figure 1

But equally important is a second type of inequality: inequality of economic opportunity. A child whose parents earn $100 million will, on average, be radically better off than a child whose parents earn $10,000. The United States has one of the highest levels of opportunity inequality among its competitors.6 In the United States, a father on average passes on roughly half of his economic advantage or disadvantage to his son. Among most of our competitors, the comparable figure is less than one-third, and for several it is less than one-fifth.7

Previous article:Consumer credit, Kyle Herkenhoff and Gordon Phillips

Next article:Monetary policy, Alan Blinder

Financial inheritances worsen this inequality of life chances dramatically. Indeed, 30 percent of the correlation between parent and child incomes—and more than 50 percent of the correlation between the wealth of parents and the wealth of their children— is attributable to financial inheritances.8 This is more than the impact of IQ, personality, and schooling combined.

Increasing the progressivity of income and payroll taxes would go a long way toward addressing both of these types of inequality.9 But it would leave significant holes if not accompanied by stronger taxes on wealth transfers. Under current law, for example, if a wealthy individual bequeaths assets with $100 million in unrealized gains, neither the donor nor the heir ever has to pay income or payroll tax on that $100 million gain. In addition, the recipients of large inheritances never have to pay income or payroll tax on the value of inheritances they receive, whether attributable to unrealized gains or not.10

Some argue that any income or payroll tax previously paid by a wealthy individual on gifts and bequests they make should count as tax paid by the heir. But they are two separate people. When a wealthy individual pays his assistant's wages out of after-tax funds, we don't think the assistant has thereby paid tax on their own wages. In short, today the income and payroll taxes effectively tax unearned income in the form of inheritances at a zero rate.

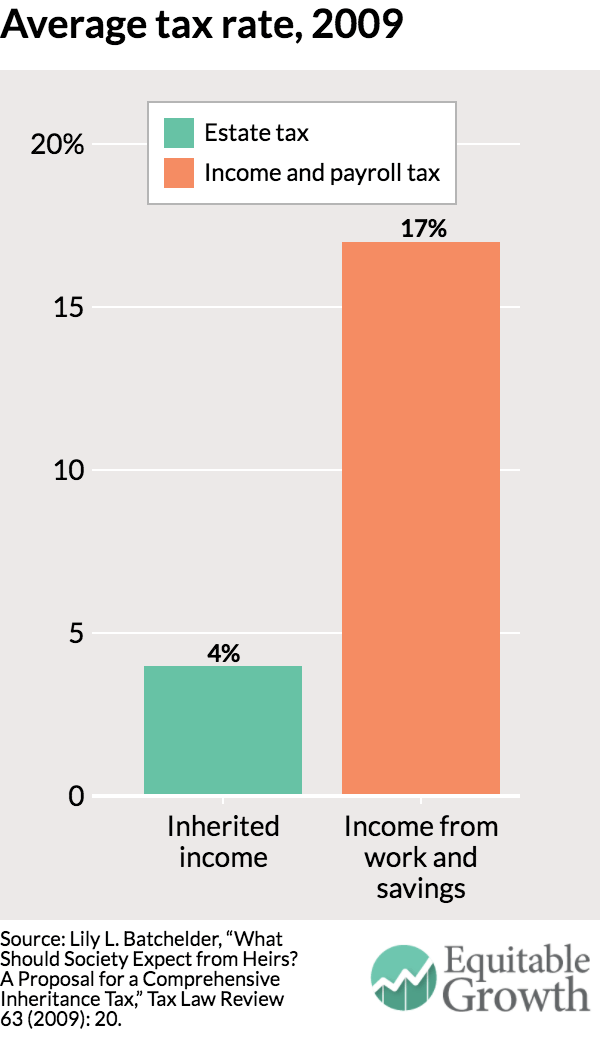

Wealth transfer taxes play an important role in partially addressing this inequity of excluding inherited income from the income and payroll tax bases.11 But inherited income is still taxed at less than one-quarter of the rate on income from work and savings. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

A fairer tax system would tax income in the form of large inheritances at a higher rate than income from work. Recipients of large inheritances are better off than people who earn the same amount of money by working. In economist-speak, they have no "opportunity cost;" they have not had to give up any leisure or earning opportunities in order to receive the inheritance. All else equal, it is therefore fairer for them to pay more taxes, not less. But all else is not equal. Heirs of large inheritances also typically have a huge leg up in earning income if they choose to work—with access to the best education, influential family friends, interest-free or low-interest loans, and a safety net if they take risks that don't pan out. This further strengthens the case for taxing inheritances at a higher rate.

More progressive income and payroll taxes cannot address this inequity in the tax system and ensure that large inheritances are taxed at higher rates than wage income.12 The same is true of proposals to adopt a tax on wealth as opposed to wealth transfers.

Importantly, bipartisan experts agree that wealth transfer taxes are largely borne by the heirs of large estates, not their benefactors.13 As a result, it would be more accurate to call wealth transfer taxes "silver spoon" taxes, not "death" taxes as their opponents prefer.

In addition to playing a critical role in making the tax system fairer, wealth transfer taxes are relatively efficient. It is an article of faith among estate tax opponents that wealth transfer taxes harm the economy because they discourage work and saving among very wealthy individuals. But in order to have these effects, the wealthy would need place a high value on the amount their heirs will inherit after-tax when making work and saving decisions. In fact, a large body of empirical research finds this is not the case, and that the amount that the affluent accumulate for wealth transfers is relatively unresponsive to the wealth transfer tax rate.14

People with very large estates typically have saved for multiple reasons. They may enjoy being wealthy, with the prestige and power that it confers while they are alive. They may have saved to have enough for their retirement needs, including unanticipated health expenses. And they may, of course, have saved to give to their children. But the empirical evidence to date suggests the first two motivations are so strong that the wealthy do not reduce their saving by all that much if they expect their estate to be taxed at a high rate. Put differently, a lot of the reason why people save is to have wealth while they are alive, which wealth transfer taxes do not affect.

Moreover, any negative incentive effects of wealth transfer taxes on wealthy donors are at least partially offset by their positive incentive effects on the next generation. Such taxes induce heirs to work and save more because heirs do not have as large an inheritance to live off of as a result.15 Wealth transfer taxes also improve business productivity. Several studies have found that businesses run by heirs perform worse because nepotism limits labor market competition for the best manager.16

For all these reasons, wealth transfer taxes may be more efficient than comparably progressive income and wealth taxes17—in addition to playing a unique role in mitigating inequality of economic opportunity.

How to strengthen

wealth transfer taxes

There are two main components of the wealth transfer tax system: the estate tax on bequests and the gift tax on wealth transfers made during life.18 In 2016, transferors are entitled to a lifetime exemption of $5.45 million ($10.9 million per couple). If their combined gifts and bequests exceed this threshold, the excess is taxed at a rate of 40 percent. Transferors also can exclude $14,000 in gifts each year to a given heir from ($28,000 per couple), meaning such gifts don't even count toward the lifetime exemption. Currently only 0.2 percent of estates owe any estate tax.19

OPTION #1: RAISE THE RATE

The simplest way to strengthen wealth transfer taxes would be to raise the rate. Restoring the 2009 estate tax parameters (a $3.5 million exemption and a 45 percent rate) would raise $160 billion over 10 years.20Also raising the rate to range from 50 percent to 65 percent to the extent that estates exceed $10 million to $1 billion would raise about $235 billion over 10 years instead.21

At a minimum, large inheritances should be taxed at the top marginal tax rate that applies to labor income—roughly 50 percent when one includes state and local income taxes.22 But a higher rate would be fairer and more efficient. The optimal tax rate on extremely large inheritances is estimated to be between 50 percent and 80 percent.23

Reducing the lifetime exemption amount also is worth considering, but it should be a lower priority. A higher rate focuses wealth transfer taxes on the wealthiest heirs and limits compliance costs.

OPTION #2: REPLACE THE ESTATE AND GIFT TAXES WITH AN INHERITANCE TAX

A more fundamental improvement would be to replace the estate and gift taxes with an inheritance tax. The lifetime exemption for the estate and gift taxes applies to the amount transferred, not the amount inherited by the heir. Suppose Richie Rich is an only child and receives $5 million in bequests from each of his parents and stepparents. Under current law, the $20 million he inherits is exempt from estate and income taxes because each bequest is under the exemption. But under an inheritance tax, the exemption would be based on how much he receives instead.

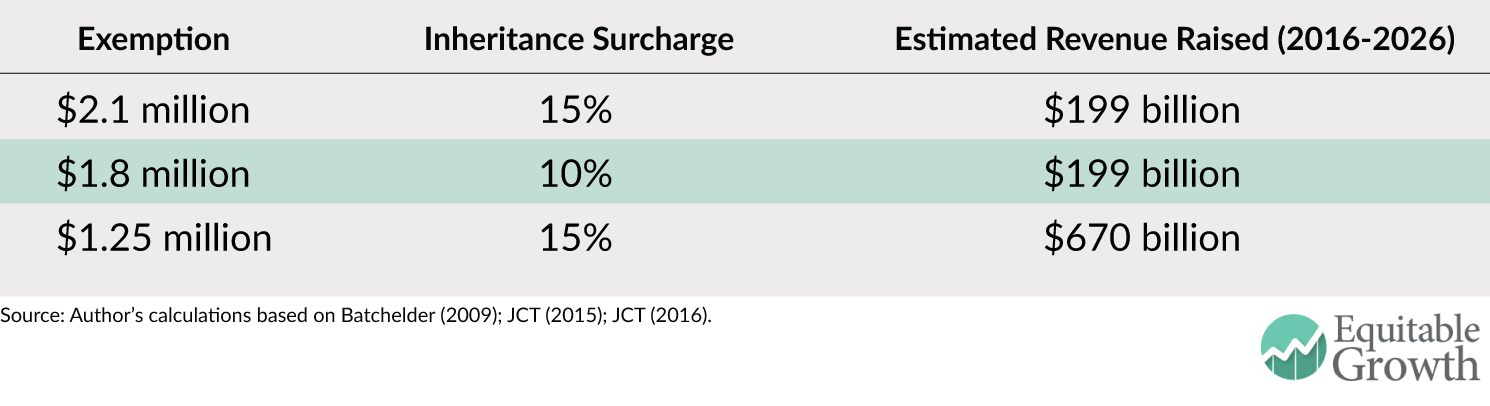

I propose requiring heirs of large inheritances to pay income tax plus an inheritance surcharge on amounts they inherit above a large lifetime exemption. If the lifetime exemption were $2.1 million and the surcharge were 15 percent (roughly equal to the maximum payroll tax rate) then such an inheritance tax would raise roughly $200 billion more over 10 years than the current estate tax. Dialing the rates up or the exemption amount down could raise more revenue. (See Figure 3.)24 To state the obvious, $2.1 million is a lot of money. An individual who inherits $2.1 million at age 21 can live off her inheritance for the rest of her life without anyone in her house ever working and, on average, her annual household income will still be higher than about 7 out of 10 American families.25

Figure 3

There are several advantages of an inheritance tax relative to an estate tax. First, it would more equitably allocate wealth transfer taxes among heirs. Both types of taxes are borne by wealthy heirs and not their benefactors. But not all large inheritances come from the largest estates, and some small inheritances come from relatively large estates.

In addition, the type of inheritance tax outlined here would apply different rates to heirs based on their total income. As a result, about 30 percent of the burden of the inheritance tax in dollar terms would fall on different heirs than under a revenue-equivalent estate tax.26 While roughly one-third of heirs burdened by the estate tax have inherited less than $1 million, none would owe any inheritance tax.27

These differences should not be taken as a fundamental critique of the estate tax. It is overwhelmingly borne by the recipients of large inheritances: Less than 4 percent of the revenue comes from individuals inheriting less than $1 million. Its burdens are just allocated among the recipients of large inheritances less precisely than under an inheritance tax.

A second, and perhaps even more important, advantage of an inheritance tax is that it could better align public understanding of wealth transfer taxes with their actual economic effects. The structure of an estate tax makes it easy for opponents to characterize it as a double tax on the frugal, generous entrepreneur who just wants to take care of his family after his death. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. The estate tax is actually the only tax that that ensures wealthy heirs pay at least some tax on their large inheritances—even if at a much lower rate than their personal assistants. But this imagery is powerful. Perhaps as a result, most countries around the world that historically had estate taxes have repealed them, while those with inheritance taxes have not.28

The structure of an inheritance tax makes the inequities of our current system clearer. It simply requires wealthy heirs to pay income tax on their large inheritances just as all American workers pay tax on their earnings. Even with a surcharge, wealthy heirs would still typically pay a lower rate of tax on their inherited income than workers pay on a similar amount of labor income because of the large exemption, which workers cannot claim on their wages.

There are ancillary advantages of an inheritance tax as well. It would be simpler because it permits a wait-and-see approach for split and contingent transfers, rather than requiring taxpayers and the Internal Revenue Service to guess upfront what portion of the transfer will ultimately go to tax-exempt individuals or charities. At the margin, it could induce the wealthy to share their estates more broadly. And it is clearly administrable. Inheritance taxes are far more common than estate taxes cross-nationally.29

OPTION #3: REPEAL STEPPED-UP BASIS

Regardless of whether the estate tax is expanded or replaced with an inheritance tax, policymakers should repeal stepped-up basis.30 This is the provision that completely exempts all accrued gains on bequeathed assets from income and payroll taxes, by "stepping up" the basis of asset to its fair market value when it is transferred.

President Obama has proposed repealing stepped-up basis, subject to several carve-outs including an exemption for the first $100,000 in accrued gains ($200,000 per couple).31 Together with raising the capital gains rate to 28 percent, this proposal would raise $210 billion over 10 years and significantly more over time as it fully phases in.32 While not technically an estate or gift tax reform, repealing stepped-up basis would accomplish all the same objectives as strengthening those taxes. It is highly progressive because inheritances are distributed so unequally and accrued gains are distributed even more unequally.33

The U.S. Department of the Treasury estimates that 99 percent of the revenue raised would come from the top 1 percent and 80 percent from the top 0.1 percent.34 It helps ensure that large inheritances are taxed at a rate closer to income from working. And it is highly efficient. Indeed, repealing stepped-up basis is even more efficient than raising wealth transfer tax rates because it reduces current law's "lock-in" incentives to hold on to underperforming assets purely for tax reasons.

If repealing stepped-up basis is not an option then the next best solution would be to apply carryover basis to bequests.35 This would allow heirs to delay paying income tax on accrued gains on their inheritances indefinitely. But heirs would at least need to pay the associated income tax when they ultimately sell the asset. As a result, it would reduce lock-in incentives, but not by nearly as much as stepped-up basis repeal. It would also raise significantly less revenue.36

OPTION #4: BROADEN THE WEALTH TRANSFER TAX BASE

A number of smaller reforms to broaden the wealth transfer tax base should also be pursued. Many of these proposals, such as limiting gaming around grantor-retained annuity trusts, are in President Obama's budget. Together, these budget proposals would raise $17 billion over 10 years.37 The next President should also finalize the current Administration's recently issued regulation addressing loopholes using valuation discounts, and ensure that Congress does not repeal it.38

An additional option worth considering is harmonizing the tax treatment of gifts and bequests. Currently gifts are often tax-advantaged because of the annual gift tax exclusion, the lack of present-value adjustments when calculating the lifetime exemption, and the fact that the top rate on very large gifts is effectively 29 percent, compared to 40 percent for bequests.39 Cutting the other way, bequests are tax-advantaged because they are eligible for stepped-up basis while gifts are not. These countervailing incentives create substantial tax planning costs, traps for the unwary, and inequities between similarly situated heirs. These problems could be largely addressed by repealing stepped-up basis, indexing the value of gifts to a market interest rate when calculating the lifetime exemption, and taxing gifts at the same rate as bequests.40

OPTION #5: ADDRESS STRAWMAN ARGUMENTS AGAINST WEALTH TRANSFER TAXES

Finally, policymakers should consider addressing talking points against wealth transfer taxes that resonate but have little or no basis in fact. A prime example is family farms. A principal rallying cry against the estate tax has long been that it forces families to sell their farms. But neither the American Farm Bureau nor The New York Times has been able to identify a single instance of this happening, even when the exemption was much lower.41

To counter this argument, one option is to adopt the proposal by former Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus (D-MT) to allow taxpayers to defer indefinitely any estate tax payments due on farm land at a market interest rate, provided the farm continues to be actively managed by the family.42 Because it is so rare for such farms and ranches to be subject to the estate tax, the proposal would only cost $5 billion over 10 years.43

To be clear, this proposal should only be considered if it is includes all the guardrails in the full Baucus proposal and interest accrues at a market interest rate. Otherwise, it could become a large loophole and reduce the number of farms owned and actively managed by families as opposed to passive investors in large corporations.

Conclusion

Wealth transfer taxes play a critical role in mitigating economic disparities, especially inequality of opportunity. The proposals offered here would soften the relative advantages of being born at the very top while leaving more than 99 percent of financial gifts and bequests unaffected.44

At the same time, these reforms options would raise a significant amount of revenue that could be used to mitigate the barriers to economic mobility that children from low- and middle-income families face. Effectively, they could fund a form of social inheritance through investments that partially make up for such families being unable to fund large financial wealth transfers to their children. The hundreds of billions of dollars raised could be used to fund universal pre-Kindergarten, expand the child tax credit for low- and middle-income working parents with young children, or increase the wage subsidy provided by the Earned Income Tax Credit for childless, frequently young adults. These proposals are estimated to significantly improve infant health, heighten academic achievement, boost labor force participation, and increase lifetime earnings for children from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds.45

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt once said "inherited economic power is as inconsistent with the ideals of this generation as inherited political power was inconsistent with the ideals of the generation which established our government." The same could be said today. Rather than falling near the bottom among our competitors on this score, we can recommit to creating a society where one's financial success depends relatively little on the circumstances of one's birth. A first step is to start taxing extraordinarily large inheritances like we tax good, old hard work.

(I am grateful to Len Burman, Michael Graetz, Chye-Ching Huang, and Wojciech Kopczuk for helpful suggestions. All errors are mine.)

END NOTES

1 James B Davies and Anthony F. Shorrocks, "The Distribution of Wealth," chap. 11 in Handbook of Income Distribution, ed. Anthony B. Atkinson and Francois Bourguignon (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2000); Edward N. Wolff and Maury Gittleman, "Inheritances and the Distribution of Wealth or Whatever Happened to the Great Inheritance Boom?," Journal of Economic Inequality 12 (2014): 439; Thomas Piketty and Gabriel Zucman, "Wealth and Inheritance in the Long Run," chap. 15 in Handbook of Income Distribution, ed. Anthony B. Atkinson and Francois Bourguignon, vol. 2B (Oxford: Elsevier 2015): 1334-42. While inheritances as a share of wealth has been rising in recent decades in several countries, it is unclear whether this is true in the U.S.

2 Lily L. Batchelder, "What Should Society Expect from Heirs? A Proposal for a Comprehensive Inheritance Tax," Tax Law Review 63 (2009): 20. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1274466

3 Ibid. $500 billion after adjusted for growth. David Joulfaian and Kathleen McGarry, "Estate and Gift Tax Incentives and Inter Vivos Giving," National Tax Journal 57 (2004): 439 tbl.5. Including transfers during life would increase this figure by about 8-16 percent.

4 Congressional Budget Office, The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes, 2013, (June 8, 2016); Linda Levine, An Analysis of the Distribution of Wealth Across Households, 1989-2010 (CRS Report No. RL33433) (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2012): 4 tbl.2.

5 Batchelder, "What Should Society Expect from Heirs," 25, fig. 4. See also Edward N. Wolff, "Inheritances and Wealth Inequality, 1989‒1998," American Economic Review, 92, no. 2 (2002): 260–64.

6 See Miles Corak, "Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility," Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (2013): 79–102.

7 Ibid.

8 Samuel Bowles, Herbert Gintis, and Melissa Osborne Groves, "Introduction," in Unequal Chances: Family Background and Economic Success (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 18-19. Financial inheritances account for 30 percent of the parent-child income correlation, while parent and child IQ, schooling, and personality combined only account for only 18 percent. Adrian Adermon, Mikael Lindahl, and Daniel Waldenström, "Intergenerational Wealth Mobility and the Role of Inheritance: Evidence from Multiple Generations," (working paper, July 26, 2016 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2831960). Bequests and gifts account for at least 50 percent of the parent-child wealth correlation, while earnings and education account for only 25 percent.

9 Lower levels of inequality are correlated with higher levels of relative intergenerational economic mobility. See Corak, "Income Inequality." However, this is less true when changes in inequality occur just in the upper tail of the economic distribution. See Raj Chetty, et al., "Is the United States Still a Land of Opportunity? Recent Trends in Intergenerational Mobility," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 19844 (2014): 11. This implies that, in order to improve relative economic mobility, more progressive taxes need not just to raise revenue from the wealthiest but also increase income after taxes and transfers for low- and middle-income households.

10 If it is saved, the earnings on those savings will be taxed, but not the amount inherited.

11 For 2016, the differential would be even larger because of cuts to the estate tax, the expiration of the high-income Bush tax cuts, and the tax increases on high-income households in the Affordable Care Act. Other income tax cuts (such as expansions to tax credits for low- and middle-income families) would partially but not fully offset these increased income taxes on the wealthy since 2009.

12 As explained below, more progressive income and payroll taxes could address this inequity if broadened to repeal exemptions specifically for inheritances.

13 "As a first approximation, it would make more sense to distribute the burden of the tax to the estate's beneficiaries rather than to the decedent." N. Gregory Mankiw, Remarks, National Bureau of Economic Research Tax Policy and the Economy Meeting from Council of Economic Advisers (Nov. 4, 2003) http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/mankiw/files/npc.pdf. For an explanation of why this is the case, see Lily L. Batchelder and Surachai Khitatrakun, "Dead or Alive: An Investigation of the Incidence of Estate Taxes and Inheritance Taxes" (working paper, 2008). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1134113

14 For a review of the empirical evidence on this issue, see Batchelder, "What Should Society Expect from Heirs," 41-44; Wojciech Kopczuk, "Taxation of Intergenerational Transfers and Wealth," chap. 6 in Handbook of Public Economics, vol. 5 (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013): 337-341.

15 See Douglas Holtz-Eakin, David Joulfaian, and Harvey S. Rosen, "The Carnegie Conjecture: Some Empirical Evidence," Quarterly Journal of Economics108, no. 2 (May 1993): 413–35; Jeffrey R. Brown, Courtney C. Coile, and Scott J. Weisbenner, "The Effect of Inheritance Receipt on Retirement," Review of Economics and Statistics 92, no. 2 (2010): 425–434.

16 See Francisco Pérez-González, "Inherited Control and Firm Performance," American Economic Review 96, no.5 (2006): 1559–88. For more studies see Batchelder, "What Should Society Expect from Heirs," note 251.

17 The empirical evidence is far from conclusive on this point and, when comparing the efficiency of different tax bases, it is important to compare comparably progressive taxes. But to a provide a rough sense, a review of the literature the elasticity of taxable income with respect to the net-of-tax income tax rate concluded that "the best available estimates range from 0.12 to 0.40." Emmanuel Saez, Joel Slemrod, and Seth H. Giertz, "The Elasticity of Taxable Income with Respect to Marginal Tax Rates: A Critical Review," Journal of Economic Literature 50 (2012): 42. In contrast, a review of the literature on the elasticity of estates to the net-of-tax estate tax rate concluded "all these papers estimate a similar baseline elasticity of net worth/reported estate estimates with respect to the net-of-tax rate of between 0.1 and 0.2." Kopczuk, "Intergenerational Transfers," 365. Several caveats are in order. These elasticities include avoidance responses as well as real behavioral changes. They are not strictly apples-to-apples because one is a stock and one is a flow. The taxable income elasticities include both capital and labor income and are not limited to the top of the income distribution. Nevertheless, they suggest that, as a first pass, wealth transfer taxes may be more efficient than comparably progressive income and wealth taxes. All of this is not to say that income taxes on high earners are as inefficient as some believe. Indeed, Saez et al., conclude in their review that "there is no compelling evidence to date of real economic responses to tax rates… at the top of the income distribution." Saez, Slemrod, and Giertz, "Elasticity of Taxable Income," 42.

18 There is also a "generation-skipping" transfer tax on transfers to heirs who are two generations younger than the donor.

19 Joint Committee on Taxation, History, Present Law, and Analysis of the Federal Wealth Transfer Tax System (JCX–52–15), (March 16, 2015): 25, tbl.2. https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4744

20 Joint Committee on Taxation, Description of Certain Revenue Provisions Contained in the President's Fiscal Year 2017 Budget Proposal (JCS-2-16), (July 21, 2016). https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4936

21 Frank Sammartino et al., "An Analysis of Senator Bernie Sanders's Tax Proposals," (Tax Policy Center, March 4, 2016 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/analysis-senator-bernie-sanderss-tax-proposals). Specifically Senator Sanders's proposal would raise the estate tax rate to 50 percent for estates between $10 million and $50 million ($20 to $100 million per couple), to 55 percent for estates between $50 million and $500 million ($100 million and $1 billion per couple), and to 65 percent for estates to the extent they exceed $500 million ($1 billion per couple).

22 This assumes a top state income tax rate of 6.6 percent. Tax Policy Center, "Individual State Income Tax Rates 2000-2015," (February 16, 2015 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/individual-state-income-tax-rates-2000-2015). Actual top state income tax rates range from 0 percent to 13.3 percent.

23 Batchelder, "What Should Society Expect from Heirs," 39–46, 50; Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, "A Theory of Optimal Inheritance Taxation," Econometrica 81, no. 5 (2013): 1851–86.

24 I have grossed up the exemptions in Batchelder, "What Should Society Expect from Heirs" for inflation, and the revenue estimates to account for the top income tax rate having risen from 35 percent to 39.6 percent since 2009 (estimates ignore FICA and SECA).

25 $2.1 million would produce inflation-adjusted annual income of about $102,000 to age 102, assuming a 5% real rate of return. The 60th percentile of household income was $72,000 in 2015 and the 80th percentile was $117,000. Bernadette D. Proctor, Jessica L. Semega, and Melissa A. Kollar, "Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015," (United States Census Bureau, September, 2016): 31, tbl. A-2. This example considers the expected, not guaranteed, consumption potential of such an heir. In order to guarantee income exceeding the 80th percentile household every year, the heir would need to purchase an annuity, which would presumably entail a lower rate of return.

26 Batchelder, "What Should Society Expect from Heirs," 76.

27 Batchelder and Khitatrakun, "Dead or Alive," 41, tbl.A14. 37% when lifetime exemption was $3.5 million.

28 Batchelder, "What Should Society Expect from Heirs," 117–18.

29 Ibid., 51.

30 For further discussion of this proposal, see David Kamin, "Taxing Capital: Paths to a Fairer and Broader U.S. Tax System," (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, August, 2016): 23–24; Laura E. Cunningham and Noël B. Cunningham, "Commentary: Realization of Gains Under the Comprehensive Inheritance Tax," Tax Law Review 63 (2009): 271–83.

31 Department of the Treasury, "General Explanations of the Administration's Fiscal Year 2017 Revenue Proposals," February 2016: 156. The proposal would also exempt all gains on the sale of tangible personal property, and would effectively establish a $500,000 per-couple exemption for gains on residences.

32 JCT, "President's FY 2017 Budget Proposal;" Kamin, "Taxing Capital," 23.

33 James Poterba and Scott Weisbenner, "The Distributional Burden of Taxing Estates and Unrealized Capital Gains at Death," in Rethinking Estate and Gift Taxation, ed. William G. Gale, James R. Hines Jr., and Joel Slemrod (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2001): 439–40. Untaxed accrued gains compose 36% of the value of all bequests, but 56 percent of bequests over $10 million.

34 Executive Office of the President and U.S. Treasury Department, The President's Plan to Help Middle-Class and Working Families Get Ahead, (April, 2015): 35, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/middle_class_and_working_families_tax_report.pdf. The distributional effects would be somewhat less concentrated if household pre-tax income was defined to include the portion of the gain accrued in the current year, rather than the full gain realized under the proposal—or if the burden of the tax was allocated to the heir(s).

35 Carryover basis currently applies to wealth transfers during life.

36 Congressional Budget Office, Budget Options (March, 2000): 311–12. This report estimated that replacing stepped-up basis with carryover basis would raise 61% of the revenue raised from repealing stepped-up basis.

37 JCT, "President's FY 2017 Budget Proposal."

38 See Estate, Gift, and Generation-Skipping Transfer Taxes, 81 Fed. Reg. 51413 (proposed August 4, 2016). For example, Sens. Rubio, Moran, and Flake have proposed legislation blocking the regulation. Protect Family Farms and Businesses Act, S. 3436, 114th Cong. (2016).

39 Unlike the estate tax, the gift tax applies to the after-tax transfer. For example, the gift tax is $40 on a pre-tax gift (above the lifetime exemption) of $140, for a tax rate of 29%.

40 For further potential base broadeners, see Paul L. Caron and James Repetti, "Revitalizing the Estate Tax: 5 Easy Pieces," Tax Notes 142, (2014): 1231–41.

41 David Cay Johnston, "Talk of Lost Farms Reflects Muddle of Estate Tax Debate," New York Times, April 8, 2001 http://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/08/us/talk-of-lost-farms-reflects-muddle-of-estate-tax-debate.html?_r=0; Michael J. Graetz and Ian Shapiro, Death by a Thousand Cuts: The Fight Over Taxing Inherited Wealth (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005): 32–40. According to the Tax Policy Center, only about 20 small business and farm estates owed any estate tax in 2013, and their average estate tax rate was 4.9%. Chye-Ching Huang and Brandon DeBot, "Ten Facts You Should Know About the Federal Estate Tax," (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 23, 2015) http://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/ten-facts-you-should-know-about-the-federal-estate-tax.

42 The Middle Class Tax Cut Act of 2010, S.A. 4727 to H.R. 4853, (proposed December 2, 2010). https://www.congress.gov/amendment/111th-congress/senate-amendment/4727/text

43 Joint Committee on Taxation, Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the Senate Amendment to H.R. 4853 (JCX-53-10), (December 2, 2010).https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=3713

44 Fewer than 0.3 percent of estates exceed $3.5 million. Tax Policy Center, "Baseline Estate Tax Returns; Current Law and Multiple Reform Proposals, 2011-2021," T11-0156 (June 1, 2011) http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/estate-tax-distribution/baseline-estate-tax-returns-current-law-and-multiple-reform. The inheritance tax proposal would similarly apply only to the most wealthy. Among those receiving a bequest, 99.1 percent inherit less than $1 million and 99.9 percent inherit less than $2.5 million. Batchelder, "What Should Society Expect from Heirs," 110, tbl. A1.

45 Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman, and Brandon DeBot, "EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children's Development, Research Finds," (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 1, 2015) http://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/6-26-12tax.pdf; Executive Office of the President and U.S. Treasury Department, The President's Proposal to Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit, (March, 2014). https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/eitc_report_0.pdf

Harpers Ferry, WV

Addressing the UN General Assembly, Trump stated openly that, "We reject the ideology of globalism, and we embrace the doctrine of patriotism." He lavished praise on other states, such as Poland, that follow his example. Should Brazilians elect the far-right presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro, they will join the wave of national populism threatening to raze the world's multilateral institutions.

Yet globalism and patriotism are not incompatible concepts. Trump's invocation of patriotism has no aim other than to whitewash his nationalist and nativist tendencies. Rhetorical traps of this type can catch us with our guard down, above all when the person who resorts to them is a leader who is known for serving his ideas raw. But it is evident that the Trump administration, too, worries about keeping up appearances.There are many other examples. At the UN, Trump sought to give his foreign policy a patina of coherence by calling it "principled realism." In international relations, realism is a theory that regards states as the central actors and units of analysis, relegating international institutions and law to an ancillary status. Principles such as human rights are usually set aside, though countries may deploy them selectively to advance their interests.

This is precisely what Trump does when he criticizes the repression of the Iranian regime, while failing to denounce similar practices in other countries. But no self-respecting realist would exaggerate the threat posed by Iran, or allow a flurry of compliments from Kim Jong-un to cloud their vision regarding North Korea.

"America will always choose independence and cooperation over global governance, control, and domination," Trump told the UN. In theory, cooperation is not incompatible with the realist paradigm. For example, realists could conceive of the US trying to offset China's geopolitical rise by bolstering its alliances in the Asia-Pacific region, especially with Japan and South Korea.

But the Trump administration has called into question the security umbrella that it provides for these countries, not even exempting them from its protectionist trade measures (although the recent update of the bilateral agreement with South Korea seems to have calmed the waters). This disconcerting behavior has extended to other traditional US allies, such as the European Union, revealing that Trump is extraordinarily reluctant to cooperate. When he does, he seldom favors the alliances that most fit his country's strategic interests.

Regarding China, US diplomacy openly uses the term "competition," despite the friendly relations that Trump claims to maintain with Xi Jinping. The ongoing trade (and technology) war between the two countries, along with the bouts of friction in the South China Sea, seem to presage an uncontrollable spiral of confrontation.

Nonetheless, this scenario (which the realist school might foresee) can be avoided, especially if we shore up the existing structures of multilateral governance, which can help us to manage shifts in the balance of power. It is clear that China does not always adhere to international norms, but the right response is to uphold these norms, not to bulldoze them. Unfortunately, the US is opting for the latter course in many areas, such as commercial relations.

In his General Assembly speech, China's foreign minister, Wang Yi, did not stress the realpolitik that his country often promotes; instead, he mentioned the concept of "win-win" no less than five times. If Trump – together with the rest of the nationalist international – continues to reject this notion of mutual benefits, he will likely manage to slow down not only China's growth, but also that of the US.

Even more alarming, spurning multilateral cooperation means dooming the world to resignation in the face of existential issues such as climate change, a negligent stance that the Trump administration has adopted with relish. America's abdication of leadership under Trump raises an obvious question: What good is it to be the world's dominant power if, in the face of the greatest global challenges, its government chooses to condemn itself to powerlessness?