Monday, March 5, 2018

The Moose Turd Cafe Podcast -- The Gunslinger and a Horse are Thirsty

Download this episode (right click and save)

The Moose Turd Cafe for 5 March 2018 opens with the Gunslinger and Hughes' (Howard?) Horse on the subject of abstractions and a genetic duel with dogma.

Some Poems that can transform the daily consumption of waste into the Profound.

- Watch Out for the Trump Tariffs -- and watch out for missing the political economics behind the Gaslighting.

- WV Teachers AND superintendents RESIST the Republican BULLSHIT.

- Further explorations into the Mystic -- The Riddle Master of Hed meets Deth, the High One's Harpist.

ALSO:

Look for drastic changes in our programming and website integration. Beginning March 8, International Women's Day: a Month of celebration of women. Till Then -- a festival of Blues, and the Dead 24-7!! Plus, the books celebrated in Dylan's Nobel address: Moby Dick, All Quiet on the Western Front, and the Odyssey. Plus War Music from the Iliad.

9 AM and Noon today: Fanny Crawford and Stas Zielkowski -- storytelling.

Tuesday @ 9:00 AM: James Boyd's Recovery Radio

Trump Administration Tries to Torpedo Venezuelan Elections as It Intensifies “Regime Change” Efforts [feedly]

http://cepr.net/publications/op-eds-columns/trump-administration-tries-to-torpedo-venezuelan-elections-as-it-intensifies-regime-change-efforts

Mark Weisbrot

US News & World Report, March 3, 2018

In recent weeks, the Trump administration has stepped up its efforts at "regime change" in Venezuela. In the past, Trump himself has even mentioned military action as a possible option, but the most recent moves appear more likely to be implemented, and some are already operational. According to sources with knowledge of the matter, the leading opposition contender for Venezuela's upcoming presidential election, Henri Falcón, was told by US officials that the Trump administration would consider financial sanctions against him if he entered the presidential race. (The US State Department did not return requests for comment.) The US has backed the main opposition coalition decision to boycott the election.

Falcón is a former governor and retired military officer. He is leading in the latest polls, and according to the most reliable opposition pollster, Datanalisis, would defeat Maduro in the election by a margin of nearly 7 percentage points.

Why would the Trump administration want to prevent an opposition leader who could possibly win the presidency in Venezuela from running in this election? There is no way to know for sure, but high-level sources from inside the administration have stated that Florida Senator Marco Rubio is determining US policy toward Venezuela. Rubio is a hard-liner who does not seem interested in an electoral or negotiated solution to Venezuela's political crisis. On February 9, he appeared to support a military coup when he tweeted: "The world would support the Armed Forces in Venezuela if they decide to protect the people & restore democracy by removing a dictator."

Such open support from Washington for a military coup against an elected government ― before the coup has occurred ― is unusual, to say the least, in the twenty-first century. But the Trump team is not just sitting around waiting for it to happen. The Rubio/Trump strategy seems to be to try to worsen the economic situation and increase suffering to the point where either the military, or the insurrectionary elements of the opposition, rise up and overthrow the government.

That appears to be the purpose of the financial sanctions that Trump ordered on August 24, 2017. These sanctions cut off Venezuela from billions of dollars of potential loans, as well as from revenue even from its own oil company in the US, Citgo. They have worsened shortages of medicine and food, in an economy that is already suffering from inflation of about 3,000 percent annually and a depression that has cost about 38 percent of GDP. These sanctions are illegal under the Organization of American States (OAS) charter and under international conventions to which the US is a signatory.

Now US officials are talking about a more ferocious collective punishment: cutting off Venezuela's oil sales. This was not done previously because it would hurt US oil refining interests that import Venezuelan oil. But the administration has floated the idea of tapping the US strategic petroleum reserves to soften the blow. All this to overthrow a government that nobody can claim poses any threat to the United States.

No one can pretend that the Trump administration cares about fair elections in Latin America. The Honduran election of November 26 was almost certainly stolen, and even Washington's close ally who heads the OAS, Secretary General Luis Almagro, called for it to be run again. But the Trump administration went with the incumbent President Juan Orlando Hernández in Honduras, a politician whose brother and security minister have been linked to drug traffickers and whom Trump Chief of Staff John Kelly, former head of the US Southern Command, has described as a "great guy" and a "good friend." The Trump administration did not object to their post-election killings of unarmed protesters or other human rights abuses ― in fact, the State Department certified the Honduran government as complying with human rights obligations just days after the election.

There are certainly valid complaints about the upcoming election in Venezuela. Some opposition candidates have been excluded, and the government moved the election forward from its initially scheduled time in December, to April. The opposition had wanted it moved forward, but this was sooner than they wanted. (On Thursday, Reuters reported that an agreement had been reached between Venezuela's election board and some opposition parties to hold the election in late May.)

Negotiations between the government and the opposition over these and other problems broke down last month, although the government did agree to allow election observers from the United Nations. With regard to the procedural credibility of Venezuela's elections, in the past two decades there has almost never been any legitimate doubt about the vote count, due to the adoption of a very secure voting system. (The only exceptions were the Constituent Assembly election of July 30 last year, which the opposition boycotted and there was some question about the number of people who voted; and one out of 23 governors' elections on October 15, where the local vote count was not credible.) For the current negotiations, we cannot know if other disagreements might have been resolved if the Trump administration had not been pushing so hard to prevent elections from taking place, and encouraging extra-legal "regime change" as an opposition strategy.

The main opposition coalition, the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD, by its acronym in Spanish), has as of now decided to boycott the elections. But it's not clear that the voters will follow their lead. The most reliable and recent polls, from Torino Capital and Datanalisis, show that 77.6 percent of voters intend to vote in the upcoming election, with only 12.3 percent planning to abstain. They should have that opportunity, and the Trump administration should not be trying to take it away from them.

Mark Weisbrot is Co-Director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C., and the president of Just Foreign Policy. He is also the author of "Failed: What the 'Experts' Got Wrong About the Global Economy" (2015, Oxford University Press). You can subscribe to his columns here.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Bernstein: Trump’s tariffs: We’re missing the bigger picture

Trump's tariffs: We're missing the bigger picture

By Jared Bernstein

I share many of these concerns. But I also fear we're all quite remarkably still missing something: Even after Trump's upset victory, Brexit, and the global rise of a populism nostalgic for a bygone era and industrial mix, political and economic elites still refuse to acknowledge and deal with those hurt by trade and globalization.

No question, these tariffs are a crude tool in that regard, likely to hurt more than they'll help. But what has the dominant policy community offered in their place? Huge tax cuts for corporations and wealthy heirs, share buybacks, and proposals to slash the safety net. Tax cuts for the rich; work requirements for the poor.

This is a policy agenda that directly violates the fundamental rationale for free trade: Yes, trade creates winners and losers, but the benefits to the winners are large enough to more than offset the losses to the losers. American economic/social policy, even after all that's transpired, still gets the first part right: more trade. But not only do the winners fail to compensate those hurt by trade, they use their winnings to buy politicians and policies that consolidate their gains while further penalizing those left behind.

Then, when our generally faux populist president actually takes a rare step, albeit misguided, to allegedly help these folks on the wrong side of globalization, all we hear is Econ 101 shouting about the distortions caused by tariffs. Like I said, I agree with much of that shouting, but colleagues, I ask you this: What else have you got?! Because if that's all we're bringing to the table, then we need to go back into our offices, shut the door and think a lot harder about a policy agenda to help lift the left behind.

I'll get back to that in a moment, but first, allow me to join the shouting. The thing about steel and aluminum is that they are "intermediate goods," i.e., inputs that show up in everything from beer cans to airplanes. Producers of these final goods will try to pass the tariff along to consumers, meaning prices will rise on a lot of what we buy. Prices will not go up 25 percent (in the case of steel), because it is one of many inputs in final products, like cars and buildings. But those marginal price increases could reduce consumer demand for a lot of products, with commensurate implications for jobs.

Second, with any tariff, even a narrowly targeted one on, for example, some low-level grade of rubber tires, the globalization cheering squad shouts "trade war!" They've seriously overplayed this hand because such narrow tariffs are extremely common, and countries engage in them all the time while continuing to engage in robust trade.

But these tariffs are not at all narrowly targeted. They apply to Chinese steel, which is legitimate in the sense that it is often underpriced, as well as steel from everywhere else. And China is not even in the top 10 of the countries from which we import steel (it is for aluminum). Most of our steel imports hail from Canada, Brazil, Mexico and South Korea; China accounts for about 2 percent of the total.

So, when close allies such as Canada talk about retaliation in this context, as they already have, they may well mean it this time. I'm much less worried about China, although I expect countervailing tariffs from them, probably on some of our agricultural exports. But given the broad scope of Trump's action, widespread retaliation feels like much more of a possibility this time around.

So, while these tariffs might pump up domestic steel and aluminum production — there is significant unused capacity in both sectors — their net impact on the economy, depending on how long they remain in place, could range from slightly negative to worse than that.

ADVERTISEMENT

But that's a partial and incomplete analysis. What matters here is not just economy, but political economy. Readers of this column know I've had almost nothing good to say about this president's economic policy agenda, as he betrays his working-class constituents at almost every turn. But there should be no question that he masterfully tuned in to their anxiety and its linkages to globalization in a way that blew the lid off the denial of the fundamental flaw in U.S.-style globalization — winners failing to compensate losers — long practiced by elites from the center left to the center right.

And yet, even after that lid was blown off, there's still no coherent policy agenda that's been articulated to help connect those who've been left behind. Instead, we hear endlessly about the stock market, trickle-down tax cuts, health "reform" that takes away what precarious coverage folks have, budgets that slice away at training programs to help displaced people regain a foothold, threats to the safety net and the social insurance programs designed explicitly to provide a backstop against poverty, ill-health and market failures.

So, to everyone complaining about these tariffs, myself included, I have one simple request. After you've vented about their economic distortions, put forth the policy initiative you think is needed to help those hurt by trade. Absent that, you may have the economics right, but unless you get the political economics right as well, it's not just that your analysis is incomplete. It's that it may well make things worse.

Harpers Ferry, WV

Bernstein: Trump’s tariffs [feedly]

http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/trumps-tariffs/

To an extent, I join with the conventional wisdom that Trump's tariffs on steel and aluminum will do more harm than good, but if that's where your analysis stops, you're not going nearly far enough: At WaPo, with more coming tomorrow or Tues (with Dean Baker).

Probably the most salient concern here is retaliation–ie, trade partners blocking our exports–though could be mitigating factors there as well. With 12% of GDP in exports, we're less exposed to countervailing tariffs than other advanced economies. Also, to the extent that retaliation generates a GDP drag from larger trade deficits (think about that, Trump), the Fed could raise less quickly–or pause in their "normalization" campaign.

Also, here's an interesting wrinkle. As I note below, most of our trade partners have good reason to object to the administration's rationale (national security risk generated by diminished capacity in sensitive industries). But since, unlike team Trump, they're likely to be more rules oriented, they might decide to take their case to the WTO, which takes at least six months to deal with such cases.

But while the Chinese dump steel below cost on global markets, most others (Canada, Brazil) do not do so, and we buy a lot more from them than we do from China. And there is no scenario I can think of wherein Canadian exports invokes "national security" risk, which was Trump's rationale for this.

So do not confuse my attempt to see some nuance here with support for Trump's actions.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Saturday, March 3, 2018

Bernstein: Stop what you’re doing and read this [feedly]

http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/stop-what-youre-doing-and-read-this/

JB: Distinguishing between growth and well-being seems fundamental to your work. How do these concepts differ? To what extent are they related?

David Pilling: Economic growth, as normally defined, is just a measure of the expansion of goods and services produced during a given period. It measures quantity, not quality. When poor countries are transforming themselves into wealthier ones, growth as measured by GDP can be a decent proxy for well-being. So long as the income generated is not being squandered on consumption or stolen by elites — hardly uncommon — raw growth can mean more education, more health care, better housing, better prospects and more material possessions. That can transform people's lives in countries like China, India and Vietnam.

But once countries reach a certain level of prosperity, the relationship between economic growth and well-being tends to break down. To put it colloquially, more stuff doesn't automatically equate to more well-being or, to put it even more colloquially, more happiness. Here I would define well-being as things like healthy life expectancy, a sense of community, low crime rates, clean air and water and how people feel about their lives.

Sometimes growth and well-being pull in opposite directions. To give just one example: We could all be richer if only we worked 10 hours more per week. Just ask the South Koreans. But at a certain point, trade-offs become important. We may decide being with our family is more important than an extra unit of output or income.

JB: A potent defense of any proposal is: It will add to GDP growth. An equally potent attack is: It will hurt growth. My read of your book is that these claims should have less policy potency, which struck as a critically important insight. But what should replace them?

DP: Here are three: Will it improve median household income, i.e. the typical person's livelihood? Will it improve health? Will it reduce carbon emissions?

JB: You write that we must do a better job measuring the value of public services, and you suggest they're undervalued. One area where this seems extremely germane is health care. How can we improve our measures of value in this area?

DP: U.S. health care "contributes" 17 percent to U.S. GDP, nearly double the proportion spent in countries, such as France, where health services are better. But bigger doesn't always mean better. We should measure the output of a health service not in dollars charged but in lives saved and health improved.

JB: You note that Adam Smith wrote about the invisible hand, not the invisible sex. Explain the overlooked, undervalued linkages between "home" and "market" production.

DP: We usually measure only activities for which money changes hands. Thus, much of the work undertaken at home, traditionally performed by women, is invisible. I'm not necessarily advocating that we estimate the value of housework and include it in GDP, though theoretically this is possible. But I am saying it is funny that, if I steal your car and sell it, that counts toward growth, but if I look after an aged relative or bring up three well-adjusted children, that does not.

JB: And by "funny," I don't think you mean "ha-ha funny." So here's a depressing question. Your book is a muscular, compelling argument for better, more inclusive data and measurement. But here in the U.S., we're stuck in a political moment where such facts are unwelcome, as can be seen in efforts to defund our statistical agencies. Do you worry you're barking at the moon?

DP: Oddly, I think the two phenomena are related. A decade ago, Nicolas Sarkozy, former French president, said that people did not recognize their own lives in the official statistics. That created, he said, a dangerous gap in perception that could damage democracy. His words were prescient. People may not trust the experts, but that means we need better experts and better facts. Statistical agencies need more money, not less. Measurement is an important part of getting the societies we want.

JB: Your comparisons of American efficiency vs. Japanese alleged inefficiencies were eye-opening. Is this a case of international statistics missing key aspects of quality and culture?

DP: Some 80 percent of advanced economies are made up of services, as opposed to manufactured goods. But GDP finds it difficult to measure services from year to year, let alone country to country. Even if you think a trip on a Japanese bullet train is worth twice the amount of a low-speed Amtrak journey, you cannot book a bullet-train ride between New York and Chicago for love nor money. We place great emphasis on the GDP of one country vs. another. But we are often not comparing like with like.

JB: At one point in the book, you pose the question: "Why have we made economic growth — measured by GDP — a proxy for what we are supposed to value in life?" I wonder if it doesn't have something to do with who wins and who loses from that formulation. What do you think?

DP: In the U.S. in the past 40 years, the lion's share of growth has gone to the top 1 percent, even the top 0.1 percent. These are the same people who fund the politicians who set the priorities. Funny that.

JB: Again with the "funny." I think it's important to underscore your view that growth, even imperfectly measured, "has the power to transform poor people's lives." Though some might mistake your work a treatise against growth, that's not the case, is it?

DP: My book is not anti-growth. Poor countries have every right to grow themselves out of poverty. But rich countries need to grow differently. They need to grow in a way that minimizes the strain on the planet and maximizes well-being. Fortunately, this is becoming easier. Think of Wikipedia, which provides all human knowledge for free. We can think of that as "growth," even though it has no negative impact on the environment and makes no direct contribution to GDP.

JB: Though you stress its limitations, put me down as a fan of Bhutan's efforts to measure gross national happiness. Should we be at least trying to move in that direction, giving more weight to well-being and less to money? Or is that just too squishy?

DP: I prefer the Canadian Index of Well-being, which asked Canadians what they most value and then tried to measure it. So as well as output, it maps things like good jobs, leisure, community and health. It's definitely not perfect, nor a viable alternative to GDP, but it is a good conversation starter. What sort of society do we want and how should we set the priorities to achieve it?

JB: Finally, you wisely conclude that it takes a village of indicators to begin to make sense out of an economy. Would we not be better off — maybe a lot better off — if we just down-weighted GDP and upweighted inequality, middle-class incomes, environmental measures and so on (measurements, I should point out, that we already have on the shelf)?

DB: Yes, that's exactly right. GDP is a useful measure, for all its faults. But it shouldn't be the Lord of Numbers. And it should never be confused — as its inventor Simon Kuznets pointed out — with well-being.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Friday, March 2, 2018

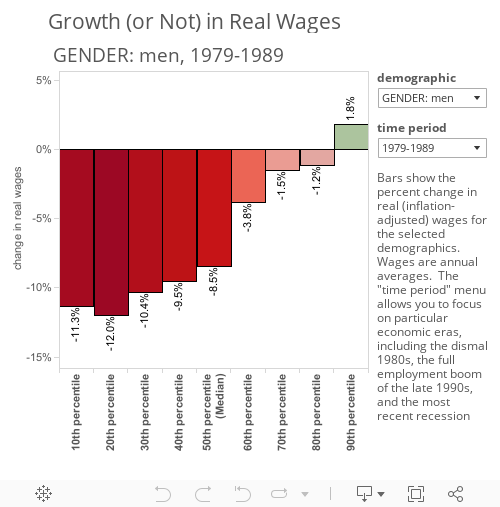

Growth (or not) in real wages [feedly]

http://www.epi.org/blog/growth-or-not-in-real-wages/

There is no starker metric for our unequal age than the stagnation of American wages over the last generation. Since 1973, productivity has grown about 75 percent, while the compensation of the typical worker has grown only about 12 percent. Since 1979, the hourly median wage has grown less than 10 percent in real dollars, or an average annual raise of barely 4 cents. While wages grew for many workers in 2017, wage growth is still far slower—and more unequal—than where it needs to be.

The interactive graphic below shows the change in real (inflation-adjusted) wages by wage decile, with drop-down filters for gender, race, educational attainment, and time period. This affords comparison of the wage gains (or losses) experienced by particular workers, and comparison across the full 1979–2017 span, or its constituent business cycles. The choice of "African-American" and "1979–1989," for example, charts how black workers fared during the dismal 1980s; the choice of "BA or higher" and "2009–2017" charts how well-educated workers fared during the long recovery from the Great Recession.

There are a lot of moving pieces here—including shifting economic opportunities, changes in educational attainment, policy drifts and shifts, and five recessions that swallow up almost 6 of the 39 years since 1979. But here are four key takeaways:

First, growing wage inequality is the rule. Most demographic and chronological slices of this data yield a steep staircase, in which wage growth is crowded into the 80th and 90thdeciles. For all workers from 1979–2017, for example, those earning at the median or below see gains of less than ten percent over that 39 year span; those at the 90th decile saw their wages rise more than 40 percent. For men, over the same era, workers at the median or below all suffer a net decrease in real wages; those at the 90th decile saw gains of over 32 percent.

Second, unions and labor standards matter. Consider the steep losses suffered by male workers (-8.5 percent at the median; -12 percent for those at the 20th decile) and by those with just a high school education in the 1980s. Union membership in the private sector fell from 21.2 percent to 6.5 percent between 1979 and 2017, with fully half of those losses coming in the 1980s (1979–1989 on the graphic). Union losses hurt women workers in the 1980s as well, but—for those in the 10th and 20th deciles—so did the fact that the minimum wage (in a long decade between legislated increases) lost over a third of its value. In the last decade (2017–2017), by contrast, there is a spike at the 10th percentile for most demographics—reflecting the profusion of state and local minimum wage increases recent years (17 states and the District of Columbia now have minimum wage of at least $9.00).

Third, full employment helps, a lot. The dismal wage record of the 1980s reflects not only union losses and slipping labor standards, but also a monthly unemployment rate that averaged nearly 8 percent over the decade. During the economic boom of the late 1990s (1995–2000 on the graphic), by contrast, near-full employment (the monthly unemployment rate average 4.9 percent over that span) conferred bargaining power even where union presence had withered. The result is not just broad-based wage growth but, for some demographics, an inverted staircase—with the highest gains at the lowest deciles.

Fourth, education is important (sort of). Returns to education are starkly evident here. Over the full 1979-2017 span, wage gains for those with a bachelor's degree or better are strong—although they are also starkly unequal. For those with a high school education or less, that staircase is upside down; losses across the board, steepest at the higher deciles. The prospects for the same educational demographics in more recent years are mixed. For those with a BA or better, only those earning above the median show any gains. For those with only some college under their belts, the returns to education elude entirely.

-- via my feedly newsfeed