By Gene Amromin , Mariacristina De Nardi , Karl Schulze

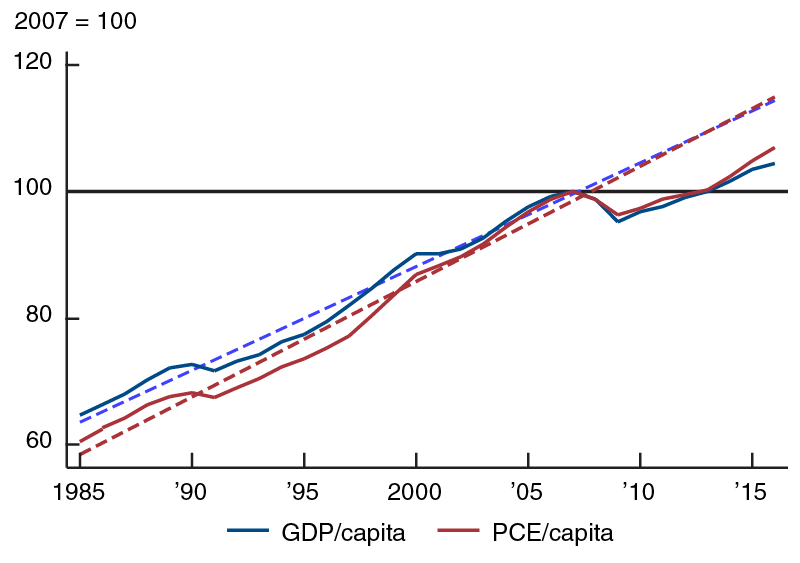

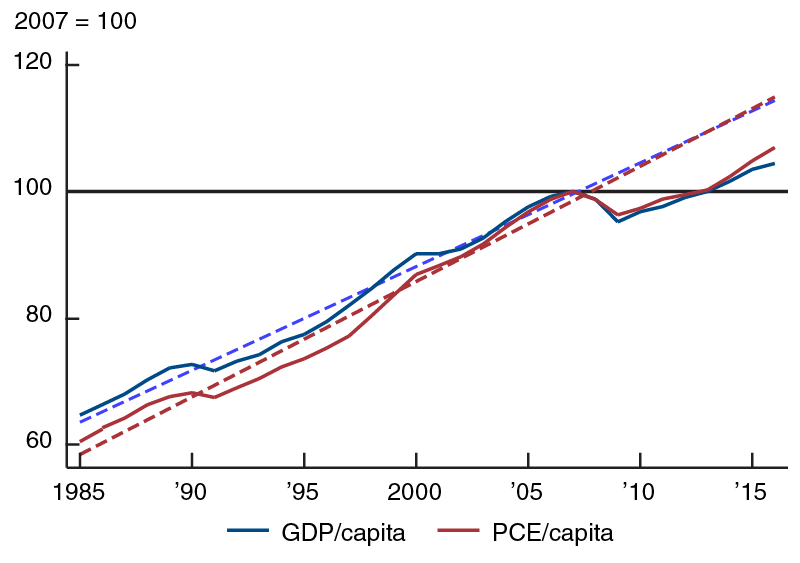

The increase in inequality over the past several decades has received widespread attention from both academics and the public at large. While much of this discourse centers on either the causes or normative implications of increasing inequality, it is important to ask whether the widening gap between the rich and poor has any direct effects on macroeconomic aggregates and, in particular, on the severity of the Great Recession, when output and consumption dropped precipitously and were slow to recover (see figure 1).1

Is it possible that the changing distribution of wealth intensified and lengthened the effects of this downturn? More broadly, should economists and policymakers concerned with macroeconomics be worried about wealth inequality?

1. U.S. real per capita GDP, PCE, and their linear trends, 1985 to 2007

In this article, we first summarize two key papers—one by Krusell and Smith (KS),2 and the other by Krueger, Mitman, and Perri (KMP).3 The major lesson from their work is that economies with a large fraction of low-wealth households, who are borrowing constrained and have a high marginal propensity to consume (MPC), can experience a larger consumption drop in response to a macroeconomic shock than economies where wealth is more evenly distributed and fewer households are borrowing constrained. Next, we turn to the Panel Study of Income Dynamics(PSID) and Credit Bureau Panel Data (Equifax) to examine the interaction between consumption and wealth during the Great Recession, highlighting several dimensions of the data that are likely to tighten the relationship between wealth inequality and the intensity of a downturn. Our recent working paper4 argues that the role of borrowing constraints cannot be adequately captured by only having a large share of households with little wealth before a recession, as is currently the case in most macroeconomic theory (Kaplan and Violante5 are a notable exception).

The first paper, KS, proposes a model of consumption and savings with incomplete capital markets and aggregate uncertainty, where wealth inequality is the cumulative result of different past labor market experiences. To proxy a recession, the authors induce a negative shock to aggregate productivity, which lowers wages and raises unemployment. This paper teaches us that aggregate consumption can depend on the shape of the wealth distribution, even though price and inflation dynamics only depend on average wealth. The intuition for this duality is that low-wealth households make up a sizable fraction of consumption and have the largest MPCs, while contributing the least to aggregate capital and price determination.

The second paper, KMP, extends KS's model to a life-cycle framework and allows for unemployment insurance. Their enriched model endogenously generates much more wealth inequality than the KS baseline economy. The authors compare the dynamics of these two models and find that the KMP version generates a larger drop in consumption in response to a downturn, even after holding the total amount of wealth in the economy fixed. Thus, increasing wealth inequality can increase the severity of a recession.

These two important papers provide convincing evidence that inequality can worsen the negative effects of a recession. However, these models still miss some important aspects of the data that characterized the Great Recession. These features include endogenous changes to wealth due to changes in asset and house prices, the composition of asset holdings, the tightening of credit standards, and the complex earnings dynamics of those who remain employed. Taking into consideration these additional elements can help provide a better picture of who is borrowing constrained and how their consumption changes when they are hit by a shock.

Our goal here is to highlight these trends using the PSID and Equifax data. The PSID is a widely used and nationally representative panel of households that observes their wealth, earnings, and consumption every two years in our data, covering from 2000 to 2012. The Equifax data set is a nationally representative sample of individual borrowers, containing data on all aspects of individual and household-level borrowing and credit. This data set allows us to characterize the experience of households prior to and during the recession.

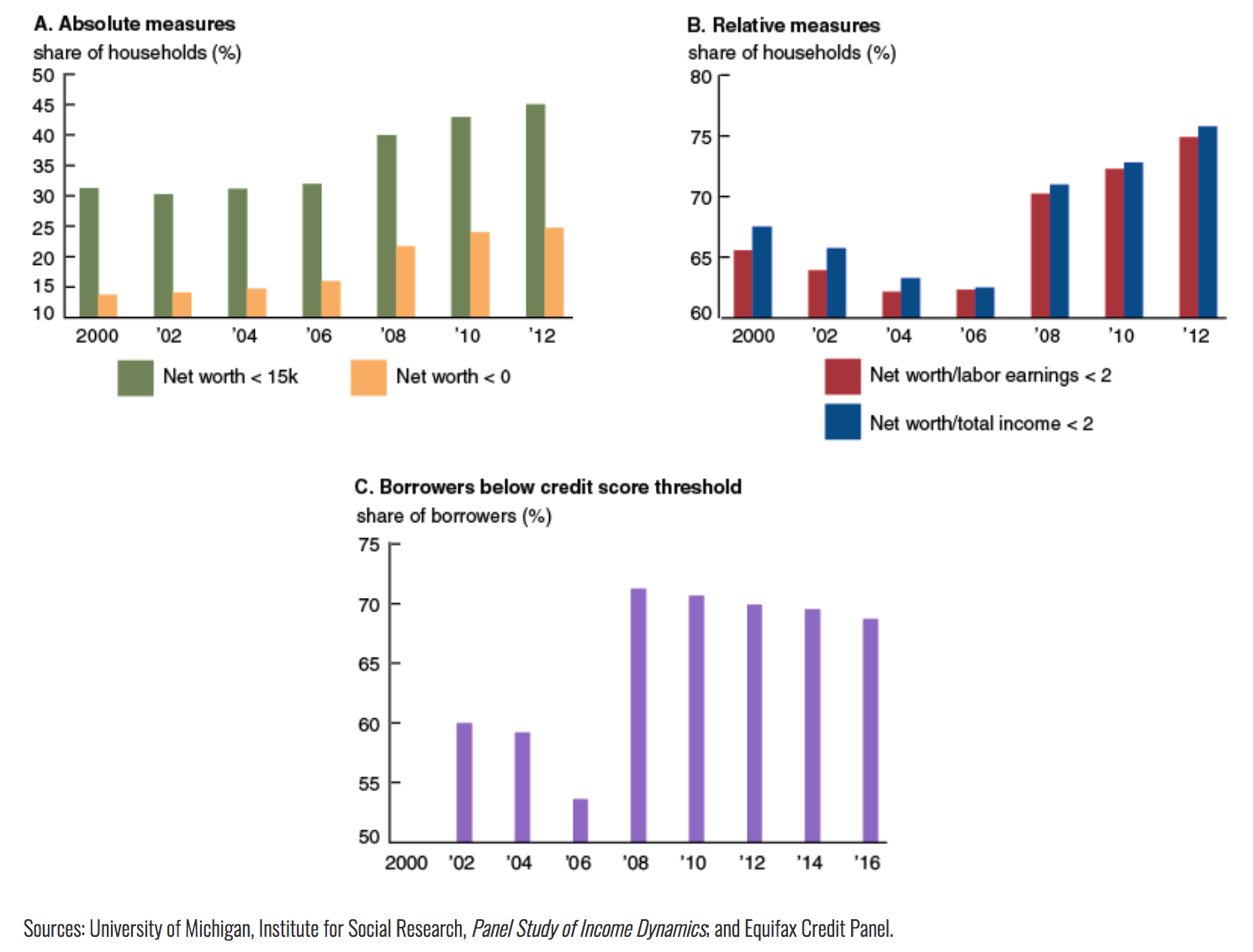

First, the models we discussed so far do not have the sizable wealth losses due to the changing asset and house values that were observed during the Great Recession. In the data, the wealth distribution shifted sharply leftward between 2006 and 2010, with the share of households holding negative net worth jumping from 16% to 24%. Moreover, the PSID shows us that changes in net worth have consequences for a household's consumption levels. In figure 2, we follow households as they transition across fixed wealth quintiles and find that downward movements in wealth are associated with negative consumption growth rates, shown in bold. For example, 43.8% of households who had net worth values between $37,400 and $133,000 remain in this group in 2010, and they experience a 0.9% per year increase in consumption. However, more than one-third of the households who were in this wealth quintile in 2006 lost enough wealth to drop into lower-wealth groups. For context, the group that transitioned from Q3 to Q1 had an average nominal net worth of $73,900 in 2006 and dropped to a 2010 mean of –$33,100. They also experienced an annualized –2.8% decline in nominal consumption during this period. Similarly, for the Q3 to Q2 group, 22.9% of households dropped from an average wealth level of $73,000 to $20,800 and experienced a –3.3% annualized decline in consumption. Therefore, asset and home values play an important role in a household's consumption and saving decisions.

Second, these models abstract from portfolio choice and the important observation that the composition of household assets changes over the wealth distribution. For example, in the PSID, only 12.7% of families in the lowest wealth quintile in 2006 owned their home, compared with 80.2% in the middle quintile. Similarly, 82.7% of families at the top of the wealth distribution held financial assets, compared with 33.6% in the middle quintile. Thus, the collapse of the housing bubble affected households differently across the wealth distribution. We calculate that 22% of families in the middle of the wealth distribution lost all of their housing wealth, compared with only 6.5% of the top quintile. In contrast, low-wealth households were less affected by housing price declines, since so few owned a home.

2. Transition probabilities and annualized nominal consumption changes (%) across 2006 net worth quintiles, 2006 to 2010

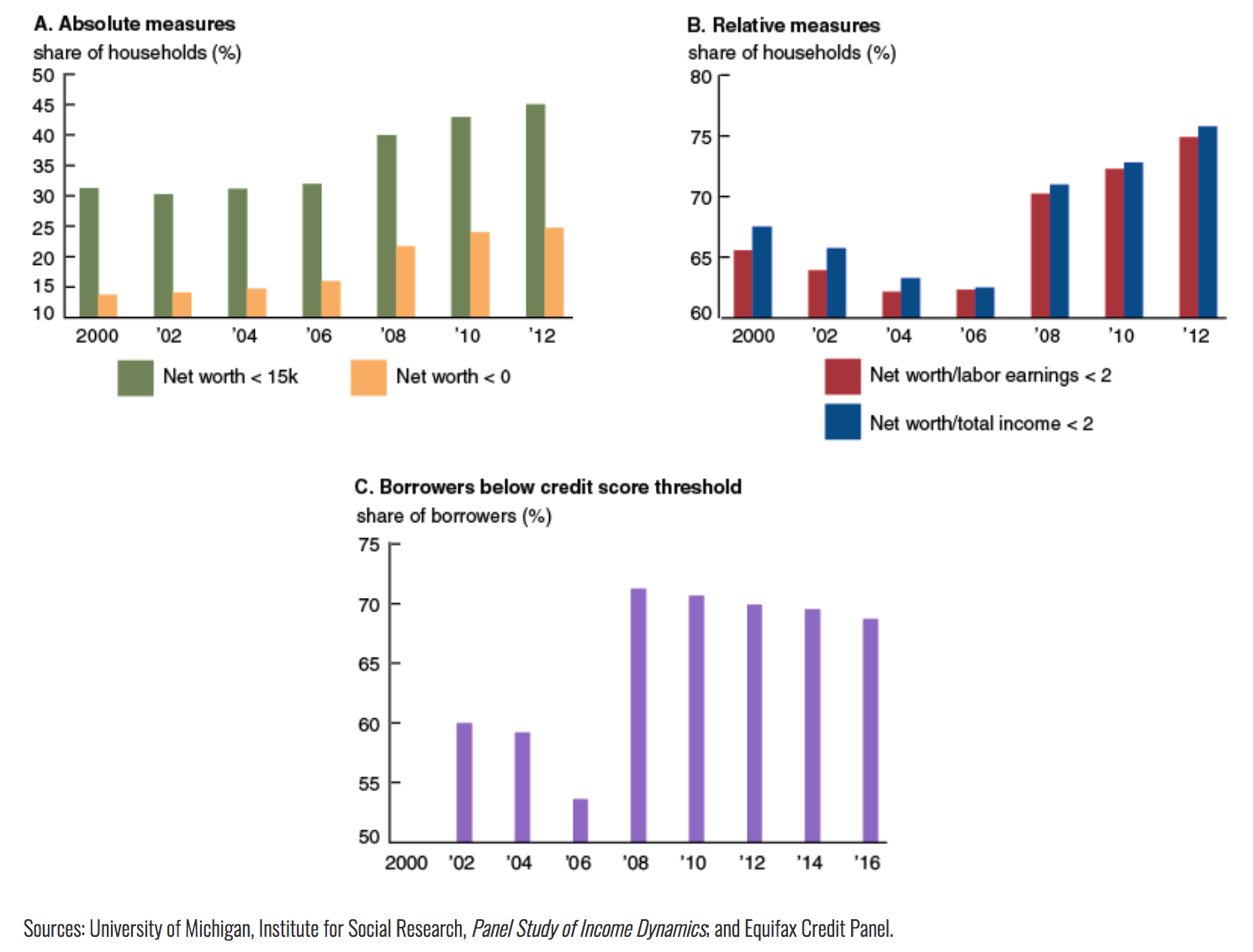

Third, the decline in asset prices and rise in unemployment occurred simultaneously with a tightening of credit standards. Guerrieri and Lorenzoni6 show that this also tends to reduce consumption. With the onset of the recession, not only did many households' credit scores decline, but financial institutions also raised their required credit score thresholds, with the median score of borrowers approved for mortgages backed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac increasing from 720 to 780. The result of this tightening was that only super-prime borrowers, i.e., those with credit scores above 779, did not see substantial declines in their success rates of obtaining credit. Importantly, for the various measures we consider in figure 3, this deterioration in the ability of households to borrow appears to not have recovered as of 2012, thus possibly contributing to the slow recovery that we have observed.

Fourth, the models only consider increases in the risk of unemployment during recessions, which tend to affect those at the bottom of the wealth distribution the most. However, in the data, changes in hours worked and earnings for those who remain employed also show substantial declines that play out differently across the wealth distribution. Downward changes in households' earnings expectations can also help explain the slow recovery of consumption after the crisis, amplifying the intensity of the initial downturn. For example, Pistaferri7 shows that declines in consumer confidence and earnings expectations explain the longer-than-normal recovery in expenditures, especially among those at the bottom of the income distribution. De Nardi, French, and Benson8 show that the recession was characterized by both permanent shocks to income and increases in income uncertainty, while Malmendier and Nagel9 use evidence from those who experienced the Great Depression to show that a financial crisis can permanently increase risk aversion among households who live through it.

3. Fraction of constrained households over time

Conclusion

The models of KS and KMP, together with these additional elements present in the data, point to the importance of thinking about borrowing constraints and marginal propensities to consume in richer frameworks in which the constraints are not simply synonymous with holding little in the way of net worth. The models also stress the consequences that unequal access to financial liquidity can have on consumption dynamics during an economic downturn. As we show, various measures of household constraints have permanently increased in the wake of the Great Recession (figure 3), raising the need for caution in thinking about an economy's response to aggregate shocks.

1 An earlier version of this article was published on VoxEU.org and is available online. The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or Federal Reserve System, National Bureau of Economic Research, Centre for Economic Policy Research, or Institute for Fiscal Studies.

2 Per Krusell and Anthony A. Smith, Jr., 1998, "Income and wealth heterogeneity in the macroeconomy," Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 106, No. 5, October, pp. 867–896.

3 Dirk Krueger, Kurt Mitman, and Fabrizio Perri, 2016, "Macroeconomics and household heterogeneity," in Handbook of Macroeconomics, John B. Taylor and Harald Uhlig (eds.), Vol. 2, Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V. / North-Holland, pp. 843–921.

4 Gene Amromin, Mariacristina De Nardi, and Karl Schulze, 2017, "Household inequality and the consumption response to aggregate real shocks," National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper, No. 24073, November.

5 Greg Kaplan and Giovanni L. Violante, 2014, "A model of the consumption response to fiscal stimulus payments," Econometrica, Vol. 82, No. 4, July, pp. 1199–1239.

6 Veronica Guerrieri and Guido Lorenzoni, 2017, "Credit crises, precautionary savings, and the liquidity trap," Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 132, No. 3, August, pp. 1427–1467.

7 Luigi Pistaferri, 2016, "Why has consumption remained moderate after the Great Recession?," Stanford University, working paper, October.

8 Mariacristina De Nardi, Eric French, and David Benson, 2012, "Consumption and the Great Recession," Economic Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 1–16.

9 Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel, 2011, "Depression babies: Do macroeconomic experiences affect risk taking?," Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 126, No. 1, February, pp. 373–416.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago