Family income inequality in the US has risen sharply in the last few decades (Stone et al. 2016). One of the consequences has been that affluent families increasingly live in different communities than lower-income families. Since most children attend a school close to their home, public schools are increasingly segregated by income (Owens 2016).

Rising inequality may also have led to increasing economic segregation between public and private schools. There is, however, surprisingly little information about whether this has happened. In recent research, we set out to learn whether this has occurred by examining trends in private school enrolments over the last 50 years (Murnane and Reardon 2017).

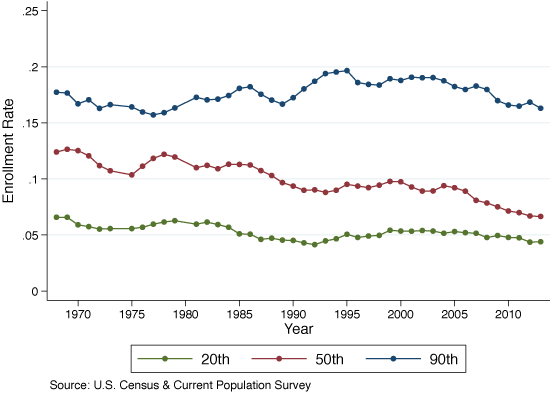

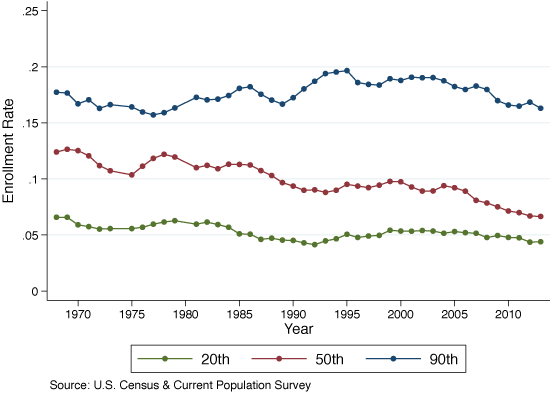

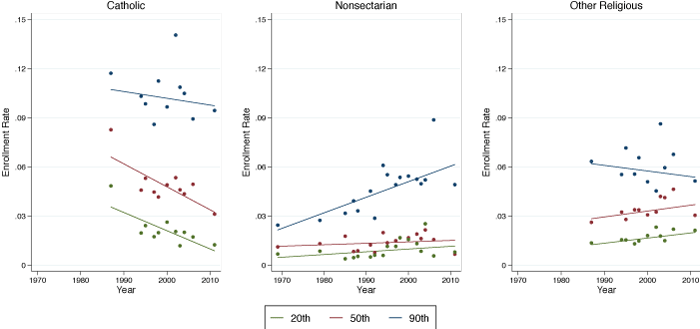

Over the last half century, the percentage of US elementary students who attend private schools has not changed much; it was 11% in 1970, and 9% in 2011. What has changed is the family income mix of private school students. In 1970, 17% of affluent students attended private schools and in 2011, 16% did so. But, among middle-class families, the enrolment rate dropped from 13% to 7%; among poor families, the rate has always been low. Figure 1 shows trends in private school enrolment rates for children from 20th, 50th, and 90th income percentile families.

Figure 1 Estimated private school enrolment rates by family income percentile

Source: US Census and Current Population Survey.

The role of Catholic elementary schools

The decline in Catholic school enrolments has contributed to the changing income mix of private school students. In 1970, 85% of elementary school students (those aged 5 to 11) in the US who were enrolled in a private school were attending a Catholic school. Low tuition fees and scholarships enabled these schools to serve a great many children from low- and middle-income families, as well as those from affluent families. Over the next 40 years, the number of Catholic elementary schools in the US declined 37%. By 2011, only 43% of private elementary school students attended Catholic schools.

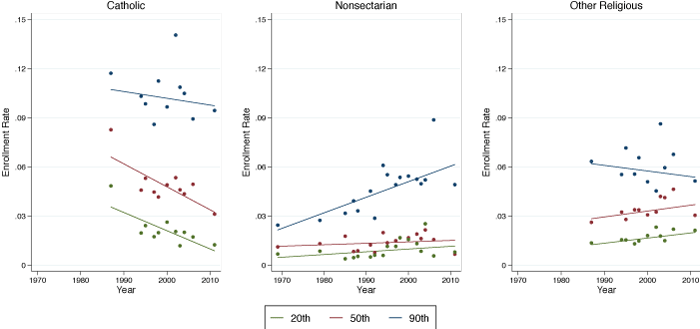

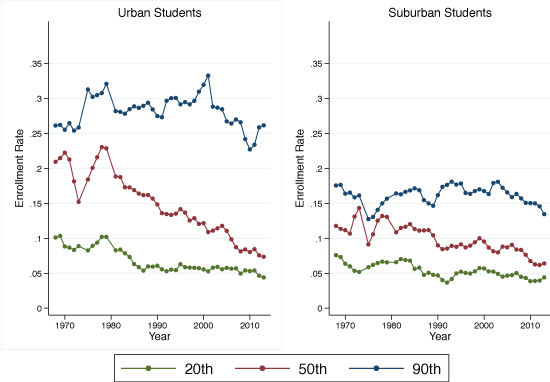

Several factors contributed to this decline in Catholic school enrolments. Migration of middle-class families from cities to suburbs deprived urban Catholic schools of much of their historic clientele. Rising costs, spurred in part by the decline in religious vocations, resulted in large increases in Catholic school tuition fees, and a reduced ability to provide scholarships. Between 1970 and 2011, the average fee for tuition in Catholic elementary schools, expressed in 2015 dollars, increased from $873 to $5,858. This far outstripped the 23% increase in the median real income of families with school-aged children during this period. As a result, Catholic elementary schools increasingly serve students from relatively high-income families (see the left-hand panel of Figure 2).

Figure 2 Estimated elementary private school enrolment by family income percentile

Source: US Census, CPS, NHES, NELS88, ECLS.

Non-sectarian private schools

In contrast to the decline in Catholic school enrolments, the number of students attending non-sectarian private elementary schools has increased in recent decades, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of private school enrolments. In 2011, these schools served 17% of all children enrolled in private elementary schools, up from 10% in 1989. Measured in 2015 dollars, the average tuition in non-sectarian private elementary schools rose from $4,120 in 1979 to $22,611 in 2011. High and rising tuition fees help to explain why enrolment in non-sectarian elementary schools is increasingly concentrated among students from high-income families. This pattern is shown in the middle panel of Figure 2.

Non-Catholic religious schools

These schools have an increasing role in private school enrolments. In 2011, these schools enrolled 40% of students attending private elementary schools, up from 33% in 1989. As with other types of private schools, a higher percentage of children from affluent families attend non-Catholic religious elementary schools than do children from middle- or low-income families.

As the right-hand panel of Figure 2 shows, enrolment trends by family income in non-Catholic religious elementary schools are different. The percentages of children from low- and middle-income families attending non-Catholic religious elementary schools increased between 1987 and 2011, while the percentage from high-income families declined. These trends seem surprising, given that tuition fees in these schools have also increased rapidly, from an average of $3,896 in 1993 to $9,134 in 2011 (in 2015 dollars).

Regional differences help explain this surprising trend. These schools, especially the subset of them known as Conservative Christian schools, are disproportionately located in the South. In 2011, 40% of children enrolled in non-Catholic religious elementary schools, and 47% of those attending Conservative Christian schools, lived in the South. After Supreme Court decisions banning prayer in schools, many conservative Christians felt that public schools did not reflect their values (Cooper 1984). This led them to send their children to schools associated with their churches, despite the high financial cost of doing so.

Perceptions of quality

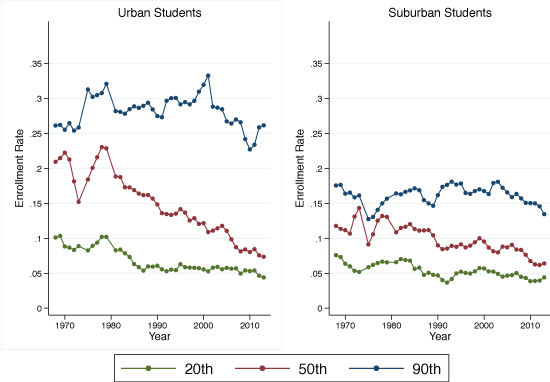

The perceived quality of the public schools with which private schools compete helps explain the patterns in private school enrolments. The increase in residential segregation by income, especially among families with school-aged children, is that urban public schools increasingly have low-income student populations (Owens 2016, Owens et al. 2016). Average mathematics and reading scores are much lower for students attending urban public schools than for those attending suburban public schools. Student discipline problems are more frequent. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s (the only period for which we have consistently coded data), urban parents with children of school age rated their local public schools as lower quality than suburban parents did. For example, in 1992, 37% of urban parents gave their local schools a grade of A or B, while 50% of suburban parents did so (Phi Delta Kappa 1992).

This may explain why more than one-quarter of students from high-income families living in cities sent their children to private schools in 2013, about the same percentage as did so in 1968. In contrast, high-income families living in suburban communities were much more likely to send their children to public schools. In consequence, urban public schools and urban private schools have less socioeconomic diversity today than they had several decades ago (see Figure 3.)

Figure 3 Estimated elementary private school enrolment by family income percentile

Source: US Census and Current Population Survey.

The impact on economic mobility

In summary, the distribution of private elementary school enrolments in the US has changed markedly over the last 45 years. Non-Catholic religious elementary schools today serve more students whose family incomes are in the bottom half of the distribution than Catholic elementary schools do. There has been substantial increase in the percentage of students from high-income families who attend private non-sectarian private schools. Much less is known about these private schools than is known about Catholic schools, which historically were the dominant supplier of private school services in the US, and the subject of a great deal of research.

The trends we documented in this paper indicate an increasingly polarised pattern of school enrolment. US schools – both public and private – are increasingly segregated by income. High-income families increasingly live either in suburbs with expensive housing or enrol their children in private schools. The private schools their children attend are more likely to be expensive non-sectarian schools than was the case four decades ago. Meanwhile, low-income students remain disproportionately concentrated in high-poverty public schools, and even those low-income students in private schools are generally not in expensive, non-sectarian private schools.

Given how difficult it is to build and sustain high quality educational programs in schools serving high concentrations of children from low-income families (Duncan and Murnane 2014), the increasing income segregation of US schools is likely to strengthen the intergenerational transmission of economic inequality, and reduce the potential for upward economic mobility.

References

Cooper, B S (1984), "The changing demography of private schools: Trends and implications", Education and Urban Society 16(4): 429-442.

Duncan, G J and R J Murnane (2014), Restoring opportunity: The crisis of inequality and the challenge for American education, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press and the Russell Sage Foundation.

Murnane, R J and S F Reardon (2017), "Long-term trends in private school enrollments by family income", NBER Working Paper No. 23571.

Owens, A (2016), "Inequality in children's contexts: Trends and correlations of economic segregation between school districts, 1990 to 2010", American Sociological Review 81(3): 549-574.

Owens, A, S F Reardon and C Jencks (2016), "Income segregation between schools and school districts", American Educational Research Journal 53(4): 1159-1197.

Phi Delta Kappa (1992), "Gallup/phi delta kappa poll # 1992-PDK92: 24th annual survey of the public's attitudes toward the public schools", Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, Cornell University.

Stone, C, D Trisi, A Sherman and E Horton (2016), A guide to statistics on historical trends in income inequality, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.