I enjoy Scott Galloway's popular podcast Prof G Markets, and I was listening to him and co-host Ed Elson discuss why the private equity giant Sycamore Partners - which specializes in squeezing blood out of failing retailers - is buying Walgreens for $10 billion. Walgreens is America's second-largest drug store chain, and has been a public company for more than 100 years. "Going private," particularly to a fund like Sycamore, is an admission of failure.

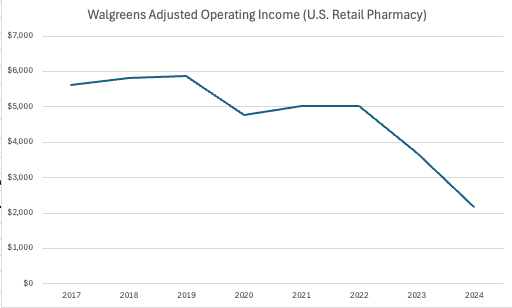

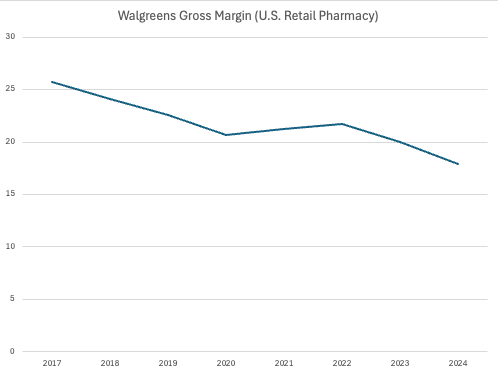

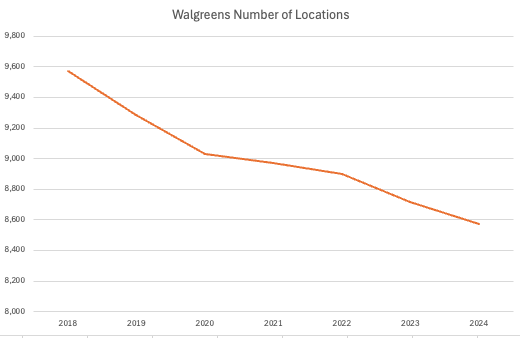

The trends for Walgreens aren't good - it has closed a thousand stores since 2018, and plans to shut 1,200 more this year. And if you look at the gross operating income of the U.S. retail segment, it is collapsing.

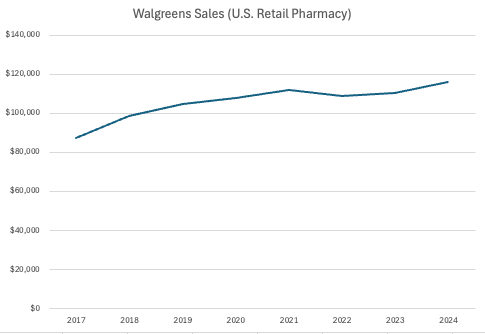

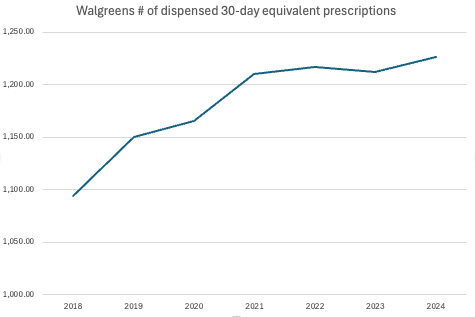

I put these charts together based on data in Walgreen's annual reports.

What's going on? Well that's simple. Margins are falling apart.

Galloway and Elson went back and forth on why Walgreens is flailing. The company hasn't modernized in the age of Amazon. It has too many stores. Bad management. A dumb acquisition of VillageMD in 2021. Etc. And these would seem like reasonable causes, since lots of other retailers are dying in the face of low price competition.

But the real reason Walgreens, and the pharmacy business in general, is dying, is because of a failure to enforce antitrust laws against unfair business methods and illegal mergers. Elson touched on it when he mentioned lower reimbursement rates, but I don't think people appreciate the full scope of what happened to Walgreens, and to the full pharmacy business in general. This is not a case of bad management, it's a case of desperate management.

Let's start by noting that on first blush, Walgreens should be fine. It's a historic company, and a historically powerful one. In 1901, pharmacist Charles Walgreen created the first Walgreens store, and he was an aggressive and entrepreneurial founder. He did some of his own drug manufacturing, and quickly expanded Walgreens to 100 stores within 25 years. The chain invented the malted milkshake in 1922, and that decade it took advantage of prohibition by selling "medicinal" alcohol. It was also a powerful chain store, not as dominant as A&P, but part of the set of firms that decade who fostered a powerful political backlash from local businesses.

And its scale remained pretty much to the present day. As late as 2015, Walgreens was worth $100 billion, an investor darling and an icon of Wall Street and America. And it's not like Amazon has come into the drug store space and taken Walgreen's margin. Yes, there is some competition, but pharmacies are regulated businesses and the consumer doesn't choose a pharmacy based on price. A doctor prescribes a drug, the consumer goes to the most convenient pharmacy and pays the copay that his or her insurance mandates. It doesn't matter what pharmacy you choose, it just matters that it's in your insurance company's network. After you've hit your deductible, the consumer price is the same wherever you go.

Moreover, even today, the other financial numbers from Walgreens aren't bad. Sales aren't going gangbusters, but the number is basically increasing, and so are the number of 30-day prescriptions, even though they've cut the number of stores every year since 2017. Its expenses, aside from a temporary a spike having to do with an unusual opioid settlement, are manageable. Here are some charts I made from their annual reports making these points.

You'd think Walgreens would be doing fine. But it's not.

So what's the explanation? It's not that the cost of physical pharmaceuticals is higher. Walgreens has market power, and they own part of Cencora, which is one of the major distributors. The problem is unique to the business of pharmacies, which is that its pricing is almost totally out of its control. Normal retailers set pricing by buying wholesale, adding a mark-up, and then selling for the wholesale price plus the markup. And Walgreens does that in a bunch of lines of business, like when you go into the store and get candy or stationary. But in its main line of business - pharmaceuticals - Walgreens doesn't set prices.

Insurance companies do. And there's the rub.

In the U.S., a consumer will go into a drug store, in this case Walgreens, after their doctor prescribes medication, and then the consumer will make a copayment. A Walgreens pharmacist then dispenses it. After doing so, Walgreens gets a set reimbursement from that consumer's insurance company for that medication. How much does it get? Well, those insurance company's contract with what's called pharmacy benefit managers (PBM) to manage negotiations with pharmacies. A PBM sets up a network for insurance companies, manages drug prices, and handles all the payment logistics between patients and pharmacies. PBMs negotiate with pharmacies, and set up a pricing agreement on which drugs are covered and how much those pharmacies get reimbursed in return for allowing those pharmacies to serve its customers.

Theoretically, both sides have some leverage in this negotiation. If a pharmacy chooses not to accept the prices and terms offered by those PBMs, then consumers who have an insurance company that uses that PBM just won't go there. PBMs also have an incentive to give reasonable terms, or at least used to, because it's valuable to have more pharmacies in your network. After all, an insurance company that doesn't let its customers shop at popular drug stores doesn't have as compelling a product.

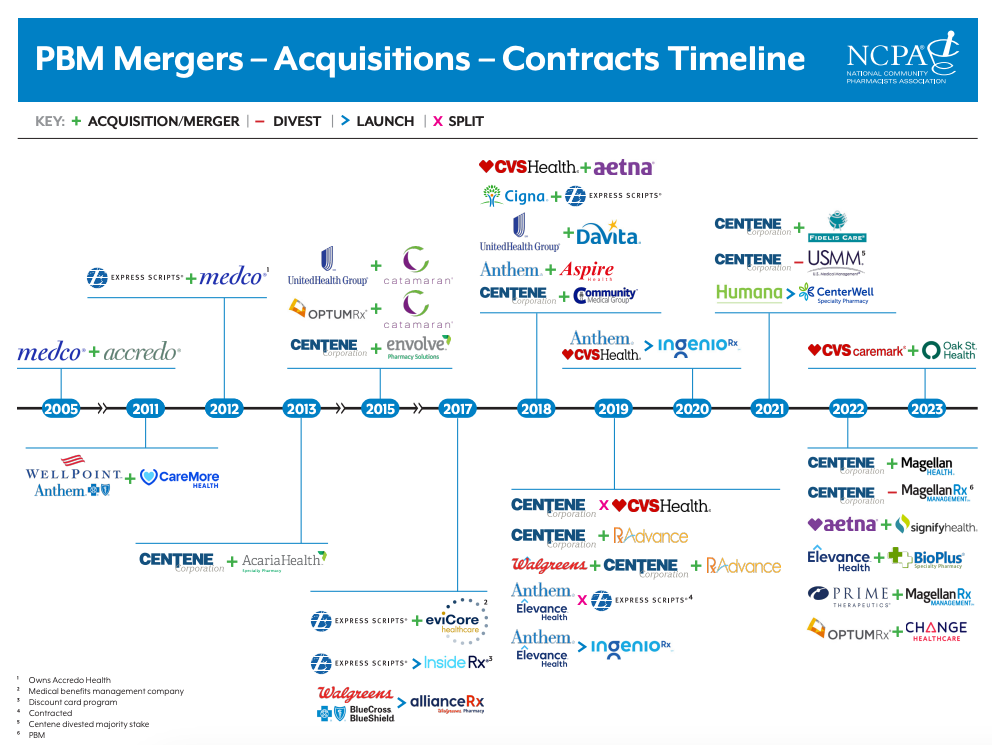

Pricing wasn't a big problem for Walgreens when there were lots of PBMs, because it had the ability to say no if the deal was unreasonable, and still maintain a flow of customers. But in the early 2010s, there were a bunch of mergers in the PBM space. Two companies, Express Scripts and Medco Health Solutions, combined in 2012, forming the biggest PBM.

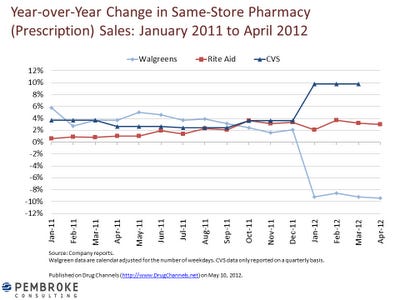

Today, there are really only three PBMs - Express Scripts, Caremark and OptumRx - serving 80% of customers. And if there are three gatekeepers for customers, you really have no choice but to sign on the dotted line, no matter the terms. No business, not even one as large as Walgreens, can afford to lose 20-30% of its revenue, which is what happens if you refuse to do business with one of the big PBMs. Here's what happened to Walgreens when it got into a fight with Express Scripts in 2012, just after the Medco-Express Scripts merger, which one industry analyst called it an "apocalypse" for the drug chain.

Walgreens eventually came back with its tail between its legs and signed a deal with Express Scripts. At that moment, it became clear that PBMs had all the power, and drug stores had none.

It got worse. In 2015, the third biggest PBM OptumRx bought the fourth largest PBM Catamaran. There were many other mergers, and this graphic is nifty, notably CVS Caremark buying Aetna in 2018. Yes, CVS, a major Walgreens competitor, is setting its revenue, which is insane. (That's why CVS's drug stores entered a host of markets while its pharmacy rivals flailed.)

Some may know about PBMs as middlemen who hike the price of drugs to consumers, sometimes taking 50% or more in rebates from drug makers. The Federal Trade Commission noted one example of a PBM marking up drug prices by as much as 7,736%. Other rebating practices are at the heart of the FTC lawsuit on insulin, and should be barred by closing the exemption in the Anti-Kickback statute.

But PBMs also impose costs on the other side of the market, to the pharmacies. In 2015, the big three, with their market power, began lowering reimbursement rates on pharmacies and charging a host of new fees. And that includes doing it even to the second biggest drug store chain in America, Walgreens, which was politically powerful and worth $100 billion at the time. Walgreens flagged it was happening at the time to Wall Street. Here's the company's annual report from that year.

We experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2015 as compared to the same period in the prior year.

They also noted that consolidation was now a business risk.

Many organizations in the healthcare industry, including PBM companies and health insurance companies, have consolidated in recent years to create larger healthcare enterprises with greater bargaining power, which has resulted in greater pricing pressures. For example, in July 2015, OptumRx, UnitedHealth Group's pharmacy care services business, completed its combination with Catamaran Corporation, with the combined businesses expected to fulfill over one billion prescriptions in 2015 and be the third largest PBM company in the United States…. If this consolidation trend continues, it could give the resulting enterprises even greater bargaining power, which may lead to further pressure on the prices for our products and services.

Well then, there we go, Walgreens warned in 2015 that monopoly power could choke out its business. And it did. The lower reimbursement rate sentence returned in the 2016 Annual Report, with an additional phrase.

We experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2016 as compared to the same period in the prior year… We expect this trend to continue.

Yes, in 2016, Walgreens realized they didn't have leverage, thus "we expect this trend to continue." Walgreens also kept the consolidation warning in there, as it did every year thereafter. And every single annual report since has had the same set of sentences. 2017

The Company experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2017 as compared to the same period in the prior year. The Company expects these pressures to continue.

2018

The Company experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2018 as compared to the same period in the prior year. The Company expects these pressures to continue.

2019

The Company experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2019 as compared to the same period in the prior year. The Company expects these pressures to continue.

2020

The Company experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2020 as compared to the same period in the prior year. The Company expects these pressures to continue.

2021

The Company experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2021 as compared to the same period in the prior year. The Company expects these pressures to continue.

2022

The Company experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2022 as compared to the same period in the prior year. The Company expects these pressures to continue.

2023

The Company experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2023 as compared to the same period in the prior year. The Company expects these pressures to continue.

2024

The Company experienced lower reimbursement rates in fiscal 2024 as compared to the same period in the prior year. The Company expects these pressures to continue.

Every single year, Walgreens told investors it was getting worse reimbursement rates, and it expected that trend to continue. Every single year, it warned investors that consolidation in PBMs was hurting its business. But rather than trying to get policymakers to act against dominant PBMs, the management got desperate, trying to find ways to imitate CVS without being able to break into the PBM layer. It went global with the acquisition of Boots Alliance, opened a specialty pharmacy, tried to get into clinical care, and bought VillageMD. The corporation even hired its current CEO, Tim Wentworth, from his position leading Express Scripts, which is the PBM that destroyed Walgreens in the first place. But none of it worked, because none of it addressed the unlawful squeezing of its revenue.

One of the big differences between Walgreens and, say, Toys "R" Us, another chain that felt the sting of Amazon, is that Walgreens is not just a company, it's a regulated medical provider. Its pharmacists are licensed, it handles controlled substances, and its employees are caregivers. That imposes significant limits and constraints, such as liability for wrongfully dispensing opioids, but it also gives it an embedded competitive advantage. There's a reason that it has lasted for 125 years, the local pharmacist is hard to get rid of.

PBMs, however, are engaged in a sort of industry-specific arson. And we can see this dynamic by looking at independent pharmacies writ large, nearly one in three of whom have closed in the last ten years. Today, 46% of U.S. counties now have pharmacy deserts, meaning no pharmacies at all. Walgreens, in some ways, is better set up than most independent pharmacies, because it's big and has bargaining power in purchasing drugs. It also has a lower cost of capital. But it's dying regardless.

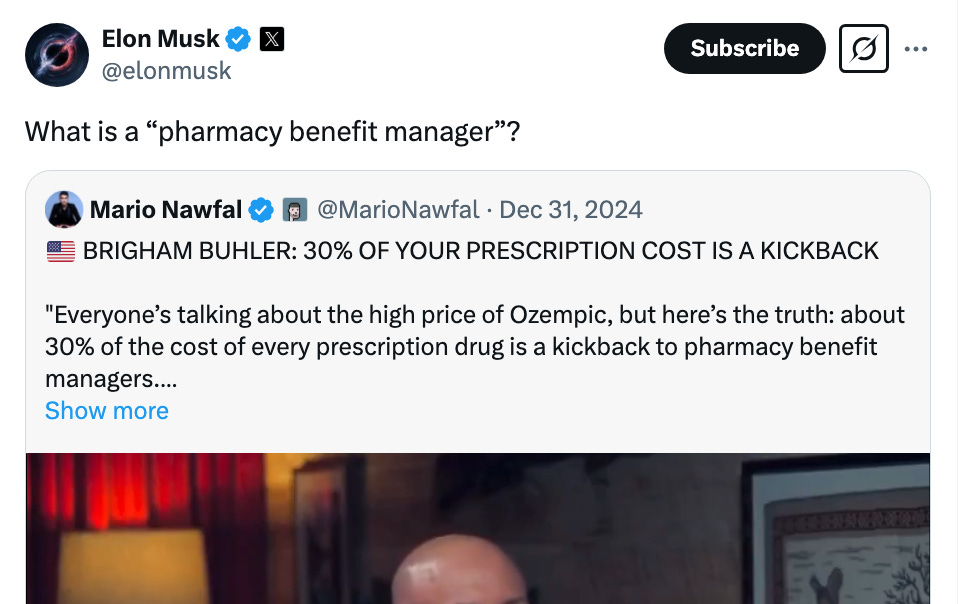

Three days ago, my organization released a report showing that 326 pharmacies have closed since December of 2024. Why is that month significant? Well, that's the month Elon Musk tanked legislation to address some of the monopolistic squeezing that PBMs are putting on pharmacies and consumers. Musk later said he didn't know what a PBM is, but at the time, his beef was that the year-end legislation had too many pages in it.

I guess we can thank Musk for the sale of Walgreens to private equity. Hopefully, Sycamore Partners realizes there's more money if PBM reform goes through, and tries to use their political leverage to make their investment work out.