The Real Reason Walgreens CollapsedIt's not that Walgreens didn't modernize or couldn't compete with Amazon. The 124 year old company is being squeezed to death by monopolistic pharmacy benefit managers.

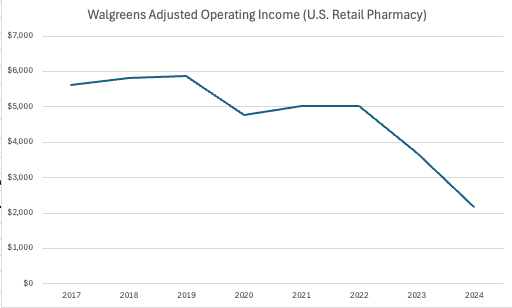

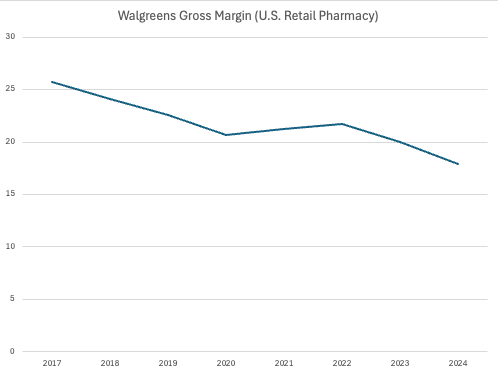

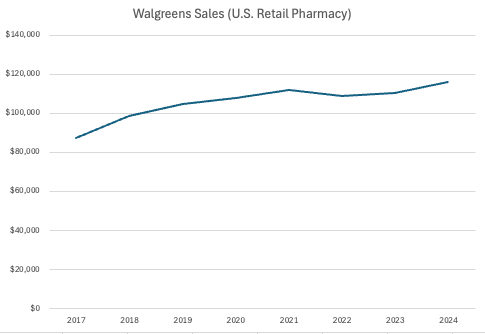

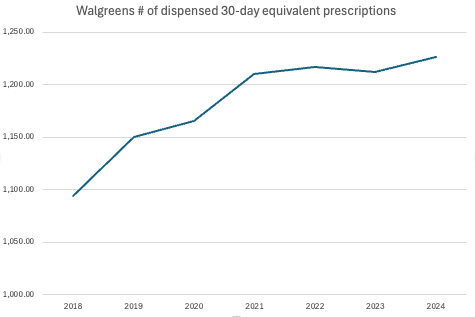

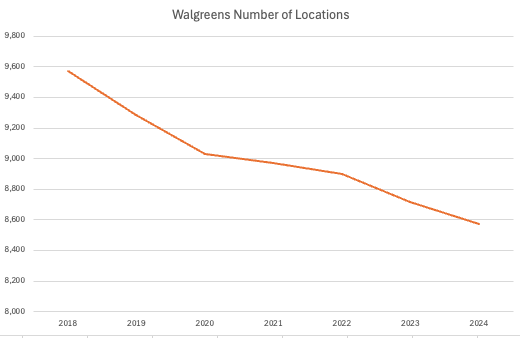

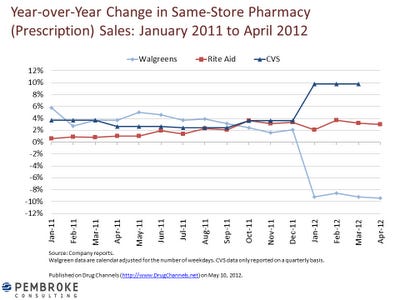

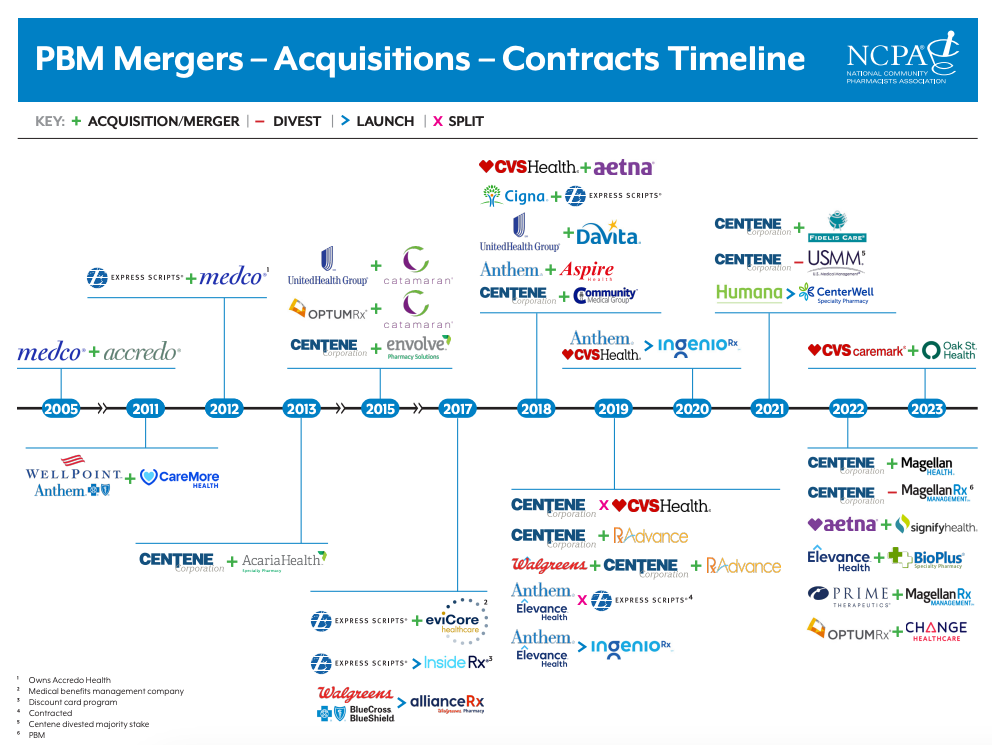

I enjoy Scott Galloway's popular podcast Prof G Markets, and I was listening to him and co-host Ed Elson discuss why the private equity giant Sycamore Partners - which specializes in squeezing blood out of failing retailers - is buying Walgreens for $10 billion. Walgreens is America's second-largest drug store chain, and has been a public company for more than 100 years. "Going private," particularly to a fund like Sycamore, is an admission of failure. The trends for Walgreens aren't good - it has closed a thousand stores since 2018, and plans to shut 1,200 more this year. And if you look at the gross operating income of the U.S. retail segment, it is collapsing. What's going on? Well that's simple. Margins are falling apart. Galloway and Elson went back and forth on why Walgreens is flailing. The company hasn't modernized in the age of Amazon. It has too many stores. Bad management. A dumb acquisition of VillageMD in 2021. Etc. And these would seem like reasonable causes, since lots of other retailers are dying in the face of low price competition. But the real reason Walgreens, and the pharmacy business in general, is dying, is because of a failure to enforce antitrust laws against unfair business methods and illegal mergers. Elson touched on it when he mentioned lower reimbursement rates, but I don't think people appreciate the full scope of what happened to Walgreens, and to the full pharmacy business in general. This is not a case of bad management, it's a case of desperate management. Let's start by noting that on first blush, Walgreens should be fine. It's a historic company, and a historically powerful one. In 1901, pharmacist Charles Walgreen created the first Walgreens store, and he was an aggressive and entrepreneurial founder. He did some of his own drug manufacturing, and quickly expanded Walgreens to 100 stores within 25 years. The chain invented the malted milkshake in 1922, and that decade it took advantage of prohibition by selling "medicinal" alcohol. It was also a powerful chain store, not as dominant as A&P, but part of the set of firms that decade who fostered a powerful political backlash from local businesses. And its scale remained pretty much to the present day. As late as 2015, Walgreens was worth $100 billion, an investor darling and an icon of Wall Street and America. And it's not like Amazon has come into the drug store space and taken Walgreen's margin. Yes, there is some competition, but pharmacies are regulated businesses and the consumer doesn't choose a pharmacy based on price. A doctor prescribes a drug, the consumer goes to the most convenient pharmacy and pays the copay that his or her insurance mandates. It doesn't matter what pharmacy you choose, it just matters that it's in your insurance company's network. After you've hit your deductible, the consumer price is the same wherever you go. Moreover, even today, the other financial numbers from Walgreens aren't bad. Sales aren't going gangbusters, but the number is basically increasing, and so are the number of 30-day prescriptions, even though they've cut the number of stores every year since 2017. Its expenses, aside from a temporary a spike having to do with an unusual opioid settlement, are manageable. Here are some charts I made from their annual reports making these points. You'd think Walgreens would be doing fine. But it's not. So what's the explanation? It's not that the cost of physical pharmaceuticals is higher. Walgreens has market power, and they own part of Cencora, which is one of the major distributors. The problem is unique to the business of pharmacies, which is that its pricing is almost totally out of its control. Normal retailers set pricing by buying wholesale, adding a mark-up, and then selling for the wholesale price plus the markup. And Walgreens does that in a bunch of lines of business, like when you go into the store and get candy or stationary. But in its main line of business - pharmaceuticals - Walgreens doesn't set prices. Insurance companies do. And there's the rub. In the U.S., a consumer will go into a drug store, in this case Walgreens, after their doctor prescribes medication, and then the consumer will make a copayment. A Walgreens pharmacist then dispenses it. After doing so, Walgreens gets a set reimbursement from that consumer's insurance company for that medication. How much does it get? Well, those insurance company's contract with what's called pharmacy benefit managers (PBM) to manage negotiations with pharmacies. A PBM sets up a network for insurance companies, manages drug prices, and handles all the payment logistics between patients and pharmacies. PBMs negotiate with pharmacies, and set up a pricing agreement on which drugs are covered and how much those pharmacies get reimbursed in return for allowing those pharmacies to serve its customers. Theoretically, both sides have some leverage in this negotiation. If a pharmacy chooses not to accept the prices and terms offered by those PBMs, then consumers who have an insurance company that uses that PBM just won't go there. PBMs also have an incentive to give reasonable terms, or at least used to, because it's valuable to have more pharmacies in your network. After all, an insurance company that doesn't let its customers shop at popular drug stores doesn't have as compelling a product. Pricing wasn't a big problem for Walgreens when there were lots of PBMs, because it had the ability to say no if the deal was unreasonable, and still maintain a flow of customers. But in the early 2010s, there were a bunch of mergers in the PBM space. Two companies, Express Scripts and Medco Health Solutions, combined in 2012, forming the biggest PBM. Today, there are really only three PBMs - Express Scripts, Caremark and OptumRx - serving 80% of customers. And if there are three gatekeepers for customers, you really have no choice but to sign on the dotted line, no matter the terms. No business, not even one as large as Walgreens, can afford to lose 20-30% of its revenue, which is what happens if you refuse to do business with one of the big PBMs. Here's what happened to Walgreens when it got into a fight with Express Scripts in 2012, just after the Medco-Express Scripts merger, which one industry analyst called it an "apocalypse" for the drug chain. Walgreens eventually came back with its tail between its legs and signed a deal with Express Scripts. At that moment, it became clear that PBMs had all the power, and drug stores had none. It got worse. In 2015, the third biggest PBM OptumRx bought the fourth largest PBM Catamaran. There were many other mergers, and this graphic is nifty, notably CVS Caremark buying Aetna in 2018. Yes, CVS, a major Walgreens competitor, is setting its revenue, which is insane. (That's why CVS's drug stores entered a host of markets while its pharmacy rivals flailed.) Some may know about PBMs as middlemen who hike the price of drugs to consumers, sometimes taking 50% or more in rebates from drug makers. The Federal Trade Commission noted one example of a PBM marking up drug prices by as much as 7,736%. Other rebating practices are at the heart of the FTC lawsuit on insulin, and should be barred by closing the exemption in the Anti-Kickback statute. But PBMs also impose costs on the other side of the market, to the pharmacies. In 2015, the big three, with their market power, began lowering reimbursement rates on pharmacies and charging a host of new fees. And that includes doing it even to the second biggest drug store chain in America, Walgreens, which was politically powerful and worth $100 billion at the time. Walgreens flagged it was happening at the time to Wall Street. Here's the company's annual report from that year.

They also noted that consolidation was now a business risk.

Well then, there we go, Walgreens warned in 2015 that monopoly power could choke out its business. And it did. The lower reimbursement rate sentence returned in the 2016 Annual Report, with an additional phrase.

Yes, in 2016, Walgreens realized they didn't have leverage, thus "we expect this trend to continue." Walgreens also kept the consolidation warning in there, as it did every year thereafter. And every single annual report since has had the same set of sentences. 2017

Every single year, Walgreens told investors it was getting worse reimbursement rates, and it expected that trend to continue. Every single year, it warned investors that consolidation in PBMs was hurting its business. But rather than trying to get policymakers to act against dominant PBMs, the management got desperate, trying to find ways to imitate CVS without being able to break into the PBM layer. It went global with the acquisition of Boots Alliance, opened a specialty pharmacy, tried to get into clinical care, and bought VillageMD. The corporation even hired its current CEO, Tim Wentworth, from his position leading Express Scripts, which is the PBM that destroyed Walgreens in the first place. But none of it worked, because none of it addressed the unlawful squeezing of its revenue. One of the big differences between Walgreens and, say, Toys "R" Us, another chain that felt the sting of Amazon, is that Walgreens is not just a company, it's a regulated medical provider. Its pharmacists are licensed, it handles controlled substances, and its employees are caregivers. That imposes significant limits and constraints, such as liability for wrongfully dispensing opioids, but it also gives it an embedded competitive advantage. There's a reason that it has lasted for 125 years, the local pharmacist is hard to get rid of. PBMs, however, are engaged in a sort of industry-specific arson. And we can see this dynamic by looking at independent pharmacies writ large, nearly one in three of whom have closed in the last ten years. Today, 46% of U.S. counties now have pharmacy deserts, meaning no pharmacies at all. Walgreens, in some ways, is better set up than most independent pharmacies, because it's big and has bargaining power in purchasing drugs. It also has a lower cost of capital. But it's dying regardless. Three days ago, my organization released a report showing that 326 pharmacies have closed since December of 2024. Why is that month significant? Well, that's the month Elon Musk tanked legislation to address some of the monopolistic squeezing that PBMs are putting on pharmacies and consumers. Musk later said he didn't know what a PBM is, but at the time, his beef was that the year-end legislation had too many pages in it. I guess we can thank Musk for the sale of Walgreens to private equity. Hopefully, Sycamore Partners realizes there's more money if PBM reform goes through, and tries to use their political leverage to make their investment work out. |

Saturday, March 15, 2025

Fwd: The Real Reason Walgreens Collapsed

Tuesday, September 3, 2024

Krugman: What former industrial heartlands have in common

the time is coming soon to take apart this almost pathetic analysis of why feeling "left behind" is caused by everything except "being left behind". This is a pernicious thread in much liberal literature, Along with "poverty would not feel so bad if everyone got therapy", IMO.

But now is not the time. All hands on deck to stop Trump --

What former industrial heartlands have in common

There were local elections in several German states a few days ago, and the results — a strong showing by the Alliance for Germany or AfD, a right-wing extremist party — were shocking but not surprising. Shocking because, given their history, Germans more than anyone else should fear the rise of anti-democratic right-wing forces. Not surprising because the AfD has been rising for a while, especially in the former East Germany, where the elections were held.

I am not any kind of an expert on Germany, and I won’t speculate about what these results mean for the Bundesrepublik’s future. What I can say as an American is that despite the vast differences in our nations’ modern histories, the rise of Germany’s modern far right — and especially its concentration of support in economically depressed areas — looks remarkably familiar.

Put it this way: In some important respects Thuringia, the German state where the AfD won more votes than any other party, resembles West Virginia. Like West Virginia, it’s a place the 21st-century economy seems to have left behind, whose population is in decline, with younger people in particular leaving for opportunities elsewhere. And West Virginia strongly supports Donald Trump and his party, whose doctrines bear considerable resemblance to those of the AfD.

After Donald Trump won the 2016 election, there was a lot of facile talk about voters driven by economic anxiety. Voters’ real motivations are more complex than that.

But MAGA’s rise does seem connected to the economic decline of much of rural and small-town America. This decline has happened in many parts of the country, including, for example, much of upstate New York, but it is concentrated in what Benjamin Austin, Edward Glaeser and Lawrence Summers have called the “eastern heartland.” In what follows I’ll focus on numbers for West Virginia, which is arguably the heart of that heartland, and epitomizes both the economic and political problems of left-behind regions.

So what stands out when you compare West Virginia with other parts of America is the number of men not working. I say “men” because even now, despite the rise in the percentage of women in the paid labor force since 1970, our expectation that adults of working age will, in fact, have jobs is stronger for men than for women.

Here’s a comparison between West Virginia and New Jersey. Why New Jersey? I’ll explain in a moment. The chart shows the percentage of adults ages 20 to 64 who didn’t have jobs in 2019 (before the pandemic):

|

| American Community Survey |

Adults of both sexes were much more likely not to be working in West Virginia, although the gap was larger for men (67 versus 43 percent).

Why is not working a problem? Obviously, it means you aren’t earning wages, but it goes deeper than that. Jobs are a source of dignity, a sense of self-worth; people who aren’t working when they feel they should be — a problem that, like it or not, is even now bigger for men than women — feel shame, which all too easily turns into anger, a desire to blame someone else and lash out.

So the lack of jobs for men helps extremist political movements that appeal to angry men. In Germany, the AfD has much stronger support among men than women. Polls show a large advantage for Kamala Harris among women in the United States, while Trump leads among men. Places where there are many men without jobs are fertile ground for MAGA, which is trying to court the “manoverse.”

Why are jobs, especially for men, so hard to get in West Virginia?

Despite what you may hear from the likes of JD Vance, native-born West Virginians aren’t losing jobs to immigrants because the state hardly has any immigrants — only 1.8 percent of the population is foreign-born, the lowest in the nation, while the corresponding number for New Jersey is 23.5 percent, close to the top.

The parallel between economic and political developments in the United States and Germany also rules out the idea that the heartland is suffering because trade deficits are undermining our manufacturing sector. For while America has indeed been running trade deficits, Germany has been running huge surpluses — yet is experiencing similar discontent and anger:

|

| World Bank |

So what’s the matter with the heartland? The most likely story is that the 21st-century economy is driven by knowledge-intensive industries that flourish in metropolitan areas with highly educated work forces. This has led to a self-reinforcing process in which jobs migrate to places with lots of college graduates, and college graduates migrate to the same places, leaving less-educated places like West Virginia stranded.

Is the solution, then, for the regions that have benefited from this process to provide aid to those on the losing end? The answer, in America at least, is that they actually do in effect provide such aid, although until recently it was the result of aid to individuals rather than reflecting a deliberate “place-based” policy.

Here’s what I mean: The federal government provides a lot of support to U.S. citizens via Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid; even poor states receive the full benefit of these programs. But poor states pay relatively little in federal taxes, which support these programs. So the result is huge implicit aid to lower-income states. Here, for 2022, are federal spending and tax receipts from West Virginia (excluding Covid-related programs), as percentages of the state’s gross domestic product:

|

| Rockefeller Institute, Bureau of Economic Analysis |

In effect, the state received “foreign aid” from wealthier states of almost 12 percent of G.D.P., which is huge.

West Virginia also benefited immensely from the Affordable Care Act, which greatly reduced the number of its residents without health insurance:

|

| KFF |

You might say that the federal social safety net increases people’s incomes but doesn’t create jobs. But that’s not true. Social Security supports consumer spending, which creates jobs in retail and more. Medicare and Medicaid support jobs in hospitals, doctors’ offices, and so on. West Virginia may still think of itself as a coal-mining state, but by the numbers it has long been more accurately described as a health care state, with much of its employment ultimately driven by those federal dollars:

|

| FRED |

I guess that there are some people who don’t think of employment in hospitals, or in the service sector more generally, as “real” jobs; I don’t think nurses and schoolteachers would agree.

What is true, and may partially explain political rage in left-behind regions, is that many of the jobs federal aid creates tend to be female-coded, certainly more so than coal mining — which may in turn explain why the problem of adults without jobs appears to be worse, at least in terms of its political weight, for men than for women.

That said, the Biden-Harris administration has been making a serious effort to promote manufacturing as part of its industrial policies — an effort that seems to be disproportionately helping heartland states.

The odd thing is that the politicians angry heartland voters support — Trump received more than twice as many votes in West Virginia as Joe Biden in 2020 — oppose the very programs that aid these depressed areas. Trump tried, in effect, to kill the Affordable Care Act. Not a single Republican voted for the Inflation Reduction Act, which is helping to create manufacturing jobs in the heartland.

But then Adam Tooze, who does know something about German political economy, tells us that while the AfD talks a lot about “social distress” in lagging regions, this “does not translate into a platform that supports greater state spending.”

In Germany as in America, then, voters in left-behind regions are, understandably, angry — and they channel this anger into support for politicians who will make their plight worse.

Saturday, August 3, 2024

Joe Stiglitz: America’s shortsighted, lopsided capitalism was never built to last

America’s shortsighted, lopsided capitalism was never built to last

by Joseph E. Stiglitz, opinion contributor 08/01/24 08:00 AM ET

Compared to almost any other economy in the world, the U.S. is in great shape today, but with three important caveats:

First, the economic divides are too great. Second, the shortsighted behavior of corporations has led to underinvestment and a lack of resilience. Third, the right’s drive to hamstring governments has led to insufficient public investment, inadequate public services and deficient regulations.

The last has resulted in a fraying infrastructure, poor health and education among large portions of an insufficiently motivated labor force and costly pollution and market power.

Despite these handicaps, the U.S. economy is performing well, with GDP growth last quarter of 2.8 percent, because of the strong stimulus provided by the landmark bills passed during the Biden-Harris administration — the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act. These bills improved infrastructure, strengthened science and helped remedy a key resilience weakness in the U.S. microchip market. Inflation has come down rapidly, as markets have worked to cure the shortages that drove up prices.

There is more that needs to be done, however.

Market power (reflected in the size of monopoly rents and markups) soared during the pandemic from already high to astronomical levels. The Biden-Harris administration began the arduous task of bringing it down, but new legislation must be passed, tempered to the 21st-century threats to the digital competitive economy.

Homelessness is a sign, in part, that our housing system is broken. A rich country should manage to do better.

Our health care system is broken, and we need to fix it. We spend far more per capita than any other country with poorer results than other advanced countries, including a lower life expectancy and greater health divides.

Climate change is an existential threat, but it is clear that even in the short run we will have to spend an increasingly large share of GDP just to repair the damage caused by extreme weather events associated with it and to adapt to rising sea levels.

The Inflation Reduction Act should be seen as the beginning of the green transition — we will need more concerted regulation, public investment and carbon pricing. We also need to become true leaders in getting the global cooperation needed to address this issue. We shouldn’t be the laggard.

Neoliberal capitalism has been markedly shortsighted. The 2008 financial crisis and the lack of resilience in the face of the pandemic are two dramatic illustrations. The greatest challenge will be to encourage more long-term thinking.

Changes in corporate governance laws and corporate thinking could make a difference, shifting from a focus on short-term stock market value maximization to a greater concern for the long-term well-being of all stakeholders, including customers, employees, the communities in which firms operate and the environment more broadly. One way to do this might be to give more voice to long-term owners through loyalty shares.

The economy faces four big threats in the short run.

First, we have a Federal Reserve that doesn’t seem to understand the sources of today’s inflation, which are sectoral shortages — including in housing — not a real excess of aggregate demand. High interest rates did not create the additional supplies of chips that brought down car prices, and high interest rates won’t create the additional housing needed to bring down housing costs. Quite the contrary. They will exacerbate these problems.

Second, if Donald Trump is elected, the reversal of key legislation of the Biden-Harris administration and the imposition of high tariffs will be highly inflationary and will slow down growth.

Third, financial deregulation will enhance the risk of another financial meltdown, and environmental deregulation will not only put us on the wrong side of history but also result in our being less competitive in the green technologies of the future.

Finally, if Trump is elected, the renewal and deepening of the Trump-era tax cuts will increase inequality, lead to less high-return public investment — when we really need more — and risk lowering even private investments. The 2017 Trump corporate tax cut did not generate more investment or growth, but it did generate larger deficits and greater inequality, with firms buying back shares and paying higher dividends to the tune of a trillion dollars or so.

As the cash in firms’ treasuries is weakened, they are less able to undertake some of the big, new profitable opportunities that come along. And savers put their money into firms whose market value has increased as a result of lower taxes and more market power, taking away funds that could and would have gone into productive investment.

In short, the greatest risk to our economy — to fixing the multiple problems I have identified — is political, with the two parties presenting two different visions for what makes for a successful economy.

One party doesn’t understand how a 21st-century economy functions and wants to return to a bygone world and undertake policies that would not reverse time but would undo the progress we’ve made and create a more dysfunctional system. It might succeed in making a few people at the top better off, but I doubt even that. When the economy doesn’t perform well even the wealthy suffer some.

The other party doesn’t offer panaceas because there are none. But it has correctly diagnosed the economy’s problems, seeks shared prosperity and has outlined a fiscally responsible strategy — although in some arenas more conservative than I would like — for achieving it.

This op-ed is part of The Hill’s “How to Fix America” series exploring solutions to some of America’s most pressing problems.

Joseph E. Stiglitz is an American economist and a professor at Columbia University. He is also the co-chair of the High-Level Expert Group on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress at the OECD and the chief economist of the Roosevelt Institute. Stiglitz was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2001.

Friday, July 12, 2024

PK calls for Biden to step down

Here are three true things about President Biden: He has done an excellent job as president. He has been ludicrously mistreated — his every verbal or physical stumble dissected and analyzed to a degree far beyond any scrutiny applied to the incoherent torrent of lies and vileness routinely issuing from Donald Trump. And he should step aside as his party’s nominee for president, probably in favor of Vice President Kamala Harris.

Anyone who has been following American politics and policy has to be aware just how remarkable Biden’s achievements have been. For decades, America seemed incapable of acting to secure its future. But Biden, despite having only a razor-thin legislative majority, enacted major investments in infrastructure, advanced technology and green energy.

He did all this while presiding over the best economic performance in the wealthy world. Yes, there was a burst of inflation as the world economy recovered from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic — but that happened almost everywhere, while growth in America, as the International Monetary Fund puts it, has been “remarkable vis-à-vis its peers,” and inflation has rapidly declined without a recession. Harsh attacks on Biden’s economic policies now look foolish.

The extent to which he has been denied credit for these achievements boggles the mind. Almost as many voters give credit for infrastructure to Trump — whose repeated promises to come up with a plan became a running joke — as to Biden, who got the job done. Everybody remembers when gas prices (over which presidents have little influence) hit $5 a gallon; far fewer took note that we just saw the lowest July 4 prices at the pump in three years.

At the same time, many Americans probably don’t have a full sense of just how bizarre and menacing Trump comes across these days. You have to watch clips from his rallies to appreciate just how disjointed and off-the-wall his speeches have become — did you hear his rant about electric boats and sharks? Until the actress Taraji P. Henson made a point of talking about the deeply un-American Project 2025 when she hosted the 2024 BET Awards, my guess is that few people knew about the project, whose leader promises a “second American Revolution,” which will remain bloodless “if the left allows it to be.”

Trump has recently tried to disassociate himself from the project, claiming that, somehow, he knows “nothing” about a plan devised by people very close to his campaign before declaring that he disagrees with “some of the things they’re saying” — a neat trick, given that he knows nothing about it — then wishing the plan’s authors luck anyway.

But here’s the thing: Last month’s presidential debate gave Biden a golden opportunity to let the American people see both who he is and who Trump is, to be calm and reassuring while Trump ranted. And Biden utterly failed the test.

The only real hope for salvaging the situation would have been for Biden to get out there as soon as possible and as often as possible to do open-ended news conferences and interviews to show that his bad night was a fluke. For whatever reason, he didn’t.

What he did instead was an interview with ABC News’s George Stephanopoulos that didn’t repair the damage. Never mind the theater of it, how he came across or whatever. The crucial moment, as I see it, was when Biden was asked how he’d feel if Trump won the election and replied, “As long as I gave it my all and I did the good as job as I know I can do, that’s what this is about.”

No, it’s not. I have huge admiration for Biden, but this isn’t a game where you get points for giving it your all and still get to feel good if that turns out not to be enough.

For this is an election with the highest possible stakes. If Trump wins, it may be the last real election — that is, an election in which the party currently holding power allows its opponents to take that power away — America will hold for a long time. If you think that’s hyperbole, after Trump tried to overturn the 2020 election, you haven’t been paying attention. So at this point it’s all about defending democracy.

Maybe we can take a lesson from the French. Faced with a threat to their democracy after their country’s far right came in first in the initial round of its parliamentary elections, many French politicians withdrew from the second round, placing the nation’s interests above their own ambitions to improve rivals’ chances of defeating antidemocratic opponents. And partly as a result, on Sunday, France’s hard right suffered a stunning and unexpected defeat.

Do we know that Biden could achieve as much for America by stepping aside now? Of course not. And we know that if Harris replaces him — at this late stage, it’s hard to see a plausible alternative — she’ll face her own wave of smears and innuendo. But she’s smart and tough, and the ugliness of the predictable attacks on her sex and race could backfire.

In any case, Biden is clearly damaged goods now, and if he insists on running, it seems all too likely that he, and possibly the future of our democracy, will lose. There’s no question in my mind that the president is a good man who loves his country. And as such, I hope he’ll do the right thing and step aside.

West Virginia GDP -- a Streamlit Version

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.

-

John Case has sent you a link to a blog: Blog: Eastern Panhandle Independent Community (EPIC) Radio Post: Are You Crazy? Reall...

-

via Bloomberg -- excerpted from "Balance of Power" email from David Westin. Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the late...

-

---- Mylan's EpiPen profit was 60% higher than what the CEO told Congress // L.A. Times - Business Lawmakers were skeptical last...