Thursday, August 27, 2020

Enlighten Radio:Talkin' Socialism: Richard Wolfe's Summary of US, Russian, and Chinese "Socialisms"

Blog: Enlighten Radio

Post: Talkin' Socialism: Richard Wolfe's Summary of US, Russian, and Chinese "Socialisms"

Link: https://www.enlightenradio.org/2020/08/talkin-socialism-richard-wolfes-summary.html

--

Powered by Blogger

https://www.blogger.com/

Tuesday, August 25, 2020

Taxing wealth and investment income in the United States [feedly]

https://equitablegrowth.org/taxing-wealth-and-investment-income-in-the-united-states/

The federal income tax does a poor job of taxing income derived from wealth. The root cause of this problem is that the tax code allows taxpayers to defer (without interest) paying tax on investment gains until assets are sold. Moreover, even when assets are sold, the investment gains are taxed at preferential rates. The top federal tax rate on wages and salaries is 37 percent while the top federal tax rate on investment gains is only 20 percent. Finally, if taxpayers can avoid selling assets until they die, the investment gains are wiped out for income tax purposes. The result is a two-tier tax system, where middle-class families pay full freight on their wages while wealthy, disproportionately White families pay reduced rates on their investment income.

Lawmakers in Congress should eliminate this two-tier system by reforming the taxation of wealth and investment income. To do so, they should adopt either a wealth tax or a reformed approach to income taxation, often referred to as mark-to-market or accrual taxation that would tax all investment gains on an annual basis regardless of whether assets are sold. Accompanying reforms to the estate tax—or the adoption of an inheritance tax—are also worth considering. The key resources below detail these solutions.

Key resources

"Taxing wealth by taxing investment income: An introduction to mark-to-market taxation," by Greg Leiserson and Will McGrew

In a system of mark-to-market taxation, investors pay tax on the increase in the value of their investments each year rather than deferring tax until those investments are sold, as they do under current law. This issue brief first defines investment income and explains how mark-to-market taxation works. It then reviews the revenue potential of this approach to taxing investment income, explaining why a mark-to-market system can raise substantial revenues. Finally, it summarizes the distribution of the burden that would result, which would fall overwhelmingly on wealthy individuals.

"Wealth taxation: An introduction to net worth taxes and how one might work in the United States," by Greg Leiserson

This brief provides an introduction to net worth taxes, also referred to as wealth taxes. It summarizes how a net worth tax works, reviews the revenue potential of such a tax, and describes the distribution of the economic burden that would be imposed.

"Net worth taxes: What they are and how they work," by Greg Leiserson, Will McGrew, and Raksha Kopparam

Wealth inequality in the United States is high and has increased sharply in recent decades. This increase—alongside a parallel increase in income inequality—has spurred increased attention on the implications of inequality for living standards and increased interest in policy instruments that can combat inequality. Taxes on wealth are a natural policy instrument to address wealth inequality and could raise substantial revenue while shoring up structural weaknesses in the current income tax system. This paper provides an introduction to net worth taxes, perhaps the most explicit means of taxing wealth.

"The 'silver spoon' tax: How to strengthen wealth transfer taxation," by Lily Batchelder

This 2016 analysis explains the case for better taxing estates or inheritances, and how lawmakers in Congress could do this. Batchelder shows how wealth transfers are extremely inequitable, currently lightly taxed, and that there are several practical solutions to resolve this problem.

"A modest tax reform proposal to roll back federal tax policy to 1997," by Owen Zidar and Eric Zwick

In the economic boom times of 1997, federal taxes raised more revenue and were a more powerful force for equity. Zwick and Zidar propose several changes that would return the United States generally to this tax system, including increasing tax rates on capital gains, dividends, and profits from pass-through businesses, as well as some additional reforms, including taxing unrealized capital gains at death.

"Taxing Wealth," by Greg Leiserson

This research paper outlines the case for major reforms to the taxation of wealth in the United States, details different approaches to reform, and discusses the economic effects of these approaches and their relative advantages and disadvantages.

Top experts

- Greg Leiserson, director of tax policy and chief economist, Washington Center for Equitable Growth

- Lily Batchelder, Frederick I. and Grace Stokes professor of law, New York University

- David Kamin, professor of law, New York University

- Emmanuel Saez, professor of economics, University of California, Berkeley, and an Equitable Growth Steering Committee member

- Gabriel Zucman, associate professor of economics, University of California, Berkeley

-- via my feedly newsfeed

As School Year Starts, Schools Face New and Lingering Challenges [feedly]

https://www.cbpp.org/blog/as-school-year-starts-schools-face-new-and-lingering-challenges

As a new school year dawns, America's schools face attacks from three directions: upended learning methods, a state revenue crisis, and racial disparities in education that threaten to weaken the quality of our children's education and our communities' economic future.

COVID-19 is making traditional education methods impossible, leaving teachers, administrators, parents, and students scrambling to devise new approaches. Educating kids safely in this pandemic would pose an enormous challenge even if our schools had all the funding they need. But, right now, they have far less than that.

That's due largely to the state revenue crisis that the virus and resulting recession have sparked, forcing states to likely make budget cuts to meet their balanced-budget requirements. With businesses closed, shoppers home, and unemployment high, income and sales taxes — upon which states overwhelmingly rely to fund education and other services — have nosedived. As a result, we estimate that states face a $555 billion shortfall through 2022. Local tax revenues are falling, too, putting local governments in a similar bind.

Schools have received some extra federal money to address the immediate costs of adapting to COVID-19, but it's far too little to cover even the necessary hand sanitizer, face shields and masks, distance-learning equipment, and other pandemic-related costs that they face, much less to replace lost revenues.

Without significant new federal aid, states and localities will likely make deep cuts to balance their budgets. Education comprises about 26 percent of state budgets, so it's a prime target. And school districts have few other funding sources: states and localities provide 47 and 45 percent of all K-12 funding, respectively.

States have sought to shield schools from cuts, but they may not be able to do so much longer. Georgia lawmakers have already cut $1 billion from the state's budget for its Education Department, and Nevada cut school funding by $160 million. New Jersey anticipates school cuts that could reach $1 billion per year. Virginia's governor is recommending that the state abandon $490 million in planned school funding.

The last time that school districts across the country cut their budgets so deeply, kids' educations suffered. In the wake of the Great Recession of a decade ago, states spent down their reserves and the sizable federal aid they received and then cut funding to K-12 schools to balance their budgets. By 2011, 17 states had cut per-student funding by more than 10 percent. As a result, local school districts cut teachers, librarians, and other staff; scaled back counseling and other services; and even reduced the number of school days.

Even in 2017, state support for K-12 schools in some states remained below pre-Great Recession levels. And school districts have never recovered from the layoffs they imposed back then. When COVID-19 hit, K-12 schools employed 77,000 fewer teachers and other workers despite teaching 1.5 million more children.

Money matters in education. As my colleague Cortney Sanders recently noted, "Adequate school funding helps raise high school completion rates, close achievement gaps, and make the future workforce more productive by boosting student outcomes, studies show." The Great Recession in particular hurt students' educations, driving down test scores and college attendance rates, Northwestern University economist C. Kirabo Jackson and two colleagues found.

Which brings us to the third big assault on public schools: Schools attended by low-income children and Black and Latino children are less well-funded, on average, than the schools of wealthier white kids — and budget cuts could hit them hardest. Unlike the virus and recession, this assault isn't new. Schools in America have been unequally funded from the start, and even the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision over six decades ago didn't end those disparities.

While state funding typically reduces disparities between wealthy and poor school districts, funding cuts magnify those disparities — and that's what happened during the Great Recession, when state funding fell as a share of total school funding. Today, in only about a third of states is total state and local funding higher in the poorest school districts — which face higher costs —than in the least-poor districts.

Now, new school funding cuts seem to be following a similar path. For example, Virginia's proposed state budget cuts are twice as large per pupil for high-poverty school districts as low-poverty districts, and 23 percent larger for the districts with many students of color than for those with mostly white students, the Commonwealth Institute reports.

This triple threat facing schools suggests that policymakers should take a similarly multifaceted approach to protect K-12 schools.

First, the President and Congress must enact a federal aid package that includes not only substantial funds earmarked for school districts but also substantial general-purpose funds to replace lost state and local tax revenues.

Second, as a condition of receiving this substantial federal aid, states and school districts must guarantee — under what would be a "maintenance of equity" requirement — that they'll protect funding for school districts that serve high shares of low-income children.

And third, states likely will need to draw down their reserves, close tax loopholes, raise new revenues, and find other ways to protect education funding and other programs that serve children and families.

The education of a generation is at stake.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Permanent job losses expected to rise, putting recovery at risk [feedly]

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/08/25/permanent-economic-damage-piles-up-covid-crisis-is-looking-more-like-great-recession/?utm_source=feedly&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=wp_business

Long-term unemployment helped define the Great Recession. Countless networks, relationships and skills that bound employee to employer were ripped apart in the global financial crisis. It took about eight years for the unemployment rate to recover from that brutal dislocation.

Now economists fear it's happening all over again. The devastating surge in unemployment in March and April was supposed to be temporary, as businesses shuttered to avert the greatest public health crisis in more than a century. Most workers reported they expected to be called back soon.

But nearly half a year later, many of the jobs that were stuck in purgatory are being lost forever. About 33 percent of the employees put on furlough in March were laid off for good by July, according to Gusto, a payroll and benefits firm whose clients include small businesses in all 50 states and D.C. Only 37 percent have been called back to their previous employer.

There were 3.7 million U.S. unemployed who had permanently lost their previous job as of July, according to the Labor Department. That figure doubled from February to June, held steady in July, and is expected to hit between 6.2 million and 8.7 million by late this year, according to a new analysis from economists Gabriel Chodorow-Reich of Harvard University and John Coglianese of the Federal Reserve Board.

The economists' most pessimistic estimate are uncomfortably close to the 8.6 million permanent unemployed seen after the Great Recession. Permanent unemployment and its cousin, long-term unemployment, are tremendous drags on an economic recovery.

AD

ADVERTISING

"We know that as people spend more time unemployed, their labor market skills atrophy, their connections to the employers weaken and many start getting discouraged and ultimately leave the workforce," said University of Chicago economist Marianne Bertrand, a leading expert on the pandemic's labor market.

The first workers sidelined in the covid-19 crisis are now closing in on 26 weeks without work, a significant milestone after which the Labor Department considers them long-term unemployed. The ranks of the long-term unemployed could swell from 1.5 million now to between 4.0 million and 5.8 million by early next year, according to Chodorow-Reich and Coglianese.

The gap between the optimistic and pessimistic scenarios is large, and the path we choose ultimately depends on whether the coronavirus can be contained. Over the past several weeks, lawmakers have been debating how much economic support is needed to limit the economic damage until the public health crisis eases. Republicans and Democrats' differing views on how to limit the damage caused by long-term unemployment is undermining their ability to come up with a stimulus deal to replace the Cares Act.

AD

Sheila Frees, 59, of Reading, Pa., thought her unemployment was temporary -- soon it will be both permanent and long-term. In March, Frees went on furlough as a part of the first wave of pandemic shutdown causalities. She waited patiently to be recalled to her job at a northeast department store until the end of June, when she was abruptly laid off.

"They drag this on for so long, and you think you're going back, and then you aren't," Frees said. "You weren't going to come back. And they knew it. If you're going to lay people off, do it quickly."

To be sure, the effects of long-term unemployment on the larger economy will be different compared with the last recession. This time, jobless benefits have been higher, at least from April through July, and public-health concerns around the novel coronavirus have effectively barred millions from working.

AD

"What's clear about this particular crisis, compared to the Great Recession, is it's affecting the least advantaged in society -- people who don't have access to other safety nets or family resources," Bertrand said. "It's not clear how these people are going to be getting by."

She added that could, paradoxically, also speed the recovery. The less-skilled, less-educated service workers who have been laid off may have an easier time finding an equivalent job in a different industry than the highly specialized workers who spent years after the Great Recession searching fruitlessly for a fit for their skills and education.

The fate of the permanent unemployed is key to understanding the political debate that has prevented Congress and the White House from coming to a deal to extend more stimulus for the unemployed and small businesses.

AD

House Democrats are concerned about the long-term prospects of the unemployed, and they passed a bill in May that would extend the $600 in weekly enhanced unemployment benefits through January.

Claudia Sahm, who worked at the Federal Reserve from 2007 through 2019, said the current crisis had gone from "unprecedented" to frighteningly similar to the Great Recession.

"Initially, the layoffs were largely temporary," said Sahm, who is now director of macroeconomic policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a progressive think tank. "In recent months, we have seen the rate of permanent layoffs rise. And we should expect more as the relief expires and more small businesses fail and more families can't go out and spend and more communities have to cut essential services."

Yet, Republicans in the Senate, as well as the White House, remain optimistic that most job losses have been and will continue to be temporary. A White House Council of Economic Advisers report out this month estimated 81 percent of layoffs from February to May were "likely to be temporary rather than permanent," citing Labor Department data. That said, the White House report acknowledged the dangers long-term unemployment poses to the economic recovery.

AD

"Before the covid-19 shutdown, the unemployment rate was below 4 percent, so we still have a long way to go in recovering lost ground. Therefore, it will be important to ensure that the decline in the unemployment rate continues over the next several months and that these temporary layoffs do not result in large permanent job losses," the report said.

Yet there are increasing signs that unemployment is becoming permanent. With every week that the pandemic rages, distressed businesses are looking at their balance sheets, and either laying off employees or closing entirely.

Americans continue to avoid crowded entertainment, shopping and dining venues, and small-business revenue has slumped. Rent, utility and insurance payments loom, and revenue prospects remain uncertain.

About 4 million U.S. businesses are expected to close this year, according to Oxxford Information Technology, which maintains a database of about 32 million businesses, nonprofits, government entities and farms. During that same period, only 1.3 million new businesses will be formed.

AD

Both figures are worse than the Great Recession, said Raymond Greenhill, Oxxford's president. In just three months from April to June, the country lost 1.85 million businesses, and Greenhill expects the losses to continue well into 2021 as businesses struggle to obtain financing and to cover expenses while operating at reduced capacity. He saw a similar pattern in the Great Recession, when businesses failures kept piling up well after the recovery had officially started.

In late May, a Census Bureau survey showed that only 38 percent of business owners thought it would take six months or more to recover normal business operations. By mid August, that number soared to 55 percent as most business owners lost hope in a speedy recovery.

According to Columbia Business School economist Laura Veldkamp, some of these behavioral changes will become permanent. The pandemic, like the Depression and the World Wars, is fundamentally altering people's tastes. Some businesses will be left behind, as consumers get accustomed to videoconferencing instead of commuting, and buying groceries online instead of braving stores, malls and restaurants.

AD

"This is a period of rapid technological change," Veldkamp said. "We are changing the way business is getting done, we're changing the way we're shopping and the way we're eating — we're changing the way we're having meetings."

As more businesses throw in the towel, more workers lose their connections to the labor market. Those connections — the years of skills, trust and social networks built up at particular employer — are exceedingly expensive and time consuming to rebuild. That's what economists are talking about when they talk about the dangers of "permanent" job loss.

"There's going to be such anxiety and such fear. Their self-esteem is impacted," said Jane Oates, president of nonprofit WorkingNation and former a Obama Labor Department official. "Obviously, some of them are going to have to retrain and learn new skills, and many of them are going to have to switch sectors."

AD

Frees, who had worked for five years as an administrative assistant, said she knows she'll survive this recession, because she survived the last one —-- though it took a whole new set of skills to do so.

After being laid off from her bookkeeping job during the Great Recession and struggling to find new work, she finally went to school and earned an associate degree. It was enough to get her work as an administrative assistant. Her new job paid less than the one she was originally laid off from, but after years of unemployment she was grateful to have any job at all.

"You don't realize that it's comforting to get up every day and get dressed and go to work and come home and make dinner," Frees said. "When you don't have that? Wow! You feel like you're out in the middle of the ocean waiting for somebody to throw you a raft."

In this recession, Frees said she believes workers like her could be adrift for a very, very long time.

"I don't think you can have a pandemic and think everything's going to snap back to normal and we'll be fine," she said. "This will get worse before this gets better."

Almost a century ago, Saul Shorr founded what would later become Harold's Kosher Market in Northern New Jersey. His son Harold took over in the 1950s and focused on fresh meat. As the city of Paramus grew into one of the New York City metro area's great retail hubs, Harold's expanded into groceries and catered food, such as soups and pastrami sandwiches, that became fixtures at Super Bowl parties and brisses.

"People came from all over to shop here," said Glen Shorr, the 66-year-old co-owner who grew up in the store. "I have customers that knew my grandfather … I have some kids who used to work here that now come in with their kids."

Harold's closed temporarily in April, when coronavirus cases were rising throughout New Jersey's suburbs. Just recently, Shorr realized it no longer made sense to keep paying insurance, rent and electric bills when the future looked so uncertain.

"It was kind of like the perfect storm," Shorr said. "Everything just kept going wrong. After a while, you just say 'I can't do it.'"

They've since donated vanloads of groceries to a local food bank. His 12 employees, some of whom had been with the store for more than three decades, will now join the ranks of the permanently unemployed — those who say they no longer have a job to go back to.

Heather Long contributed to this report.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

The Way Out Through State and Local Aid: Bipartisan group of economists breaks down why local governments need aid now [feedly]

https://www.epi.org/blog/state-and-local-aid-bipartisan-economists-video/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Friday, August 21, 2020

Stocks Are Soaring. So Is Misery. [feedly]

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/20/opinion/stock-market-unemployment.html

On Tuesday, the S&P 500 stock index hit a record high. The next day, Apple became the first U.S. company in history to be valued at more than $2 trillion. Donald Trump is, of course, touting the stock market as proof that the economy has recovered from the coronavirus; too bad about those 173,000 dead Americans, but as he says, "It is what it is."

But the economy probably doesn't feel so great to the millions of workers who still haven't gotten their jobs back and who have just seen their unemployment benefits slashed. The $600 a week supplemental benefit enacted in March has expired, and Trump's purported replacement is basically a sick joke.

Even before the aid cutoff, the number of parents reporting that they were having trouble giving their children enough to eat was rising rapidly. That number will surely soar in the next few weeks. And we're also about to see a huge wave of evictions, both because families are no longer getting the money they need to pay rent and because a temporary ban on evictions, like supplemental unemployment benefits, has just expired.

But how can there be such a disconnect between rising stocks and growing misery? Wall Street types, who do love their letter games, are talking about a "K-shaped recovery": rising stock valuations and individual wealth at the top, falling incomes and deepening pain at the bottom. But that's a description, not an explanation. What's going on?

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

The first thing to note is that the real economy, as opposed to the financial markets, is still in terrible shape. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York's weekly economic index suggests that the economy, although off its low point a few months ago, is still more deeply depressed than it was at any point during the recession that followed the 2008 financial crisis.

Give the gift they'll open every day.

Subscriptions to The Times. Starting at $25.

And this time around, job losses are concentrated among lower-paid workers — that is, precisely those Americans without the financial resources to ride out bad times.

What about stocks? The truth is that stock prices have never been closely tied to the state of the economy. As an old economists' joke has it, the market has predicted nine of the last five recessions.

Stocks do get hit by financial crises, like the disruptions that followed the fall of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 and the brief freeze in credit markets back in March. Otherwise, stock prices are pretty disconnected from things like jobs or even G.D.P.

Editors' Picks

They're Teens Biking Across a Turbulent Country. The Lessons Keep Coming.

15 Creative Women for Our Time

Shhh! We're Heading Off on Vacation

Continue reading the main story

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

And these days, the disconnect is even greater than usual.

For the recent rise in the market has been largely driven by a small number of technology giants. And the market values of these companies have very little to do with their current profits, let alone the state of the economy in general. Instead, they're all about investor perceptions of the fairly distant future.

Take the example of Apple, with its $2 trillion valuation. Apple has a price-earnings ratio — the ratio of its market valuation to its profits — of about 33. One way to look at that number is that only around 3 percent of the value investors place on the company reflects the money they expect it to make over the course of the next year. As long as they expect Apple to be profitable years from now, they barely care what will happen to the U.S. economy over the next few quarters.

Furthermore, the profits people expect Apple to make years from now loom especially large because, after all, where else are they going to put their money? Yields on U.S. government bonds, for example, are well below the expected rate of inflation.

And Apple's valuation is actually less extreme than the valuations of other tech giants, like Amazon or Netflix.

So big tech stocks — and the people who own them — are riding high because investors believe that they'll do very well in the long run. The depressed economy hardly matters.

Unfortunately, ordinary Americans get very little of their income from capital gains, and can't live on rosy projections about their future prospects. Telling your landlord not to worry about your current inability to pay rent, because you'll surely have a great job five years from now, will get you nowhere — or, more accurately, will get you kicked out of your apartment and put on the street.

So here's the current state of America: Unemployment is still extremely high, largely because Trump and his allies first refused to take the coronavirus seriously, then pushed for an early reopening in a nation that met none of the conditions for resuming business as usual — and even now refuse to get firmly behind basic protective strategies like widespread mask requirements.

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

Despite this epic failure, the unemployed were kept afloat for months by federal aid, which helped avert both humanitarian and economic catastrophe. But now the aid has been cut off, with Trump and allies as unserious about the looming economic disaster as they were about the looming epidemiological disaster.

So everything suggests that even if the pandemic subsides — which is by no means guaranteed — we're about to see a huge surge in national misery.

Oh, and stocks are up. Why, exactly, should we care?

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We'd like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here's our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

Paul Krugman has been an Opinion columnist since 2000 and is also a Distinguished Professor at the City University of New York Graduate Center. He won the 2008 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his work on international trade and economic geography. @PaulKrugman

A version of this article appears in print on Aug. 21, 2020, Section A, Page 27 of the New York edition with the headline: Stocks Are Soaring. So Is Misery.. Order Reprints | Today's Paper | Subscribe

-- via my feedly newsfeed

UI claims remain historically high and the president’s sham executive memorandum is doing next to nothing: Congress must reinstate the $600 [feedly]

https://www.epi.org/blog/ui-claims-remain-historically-high-and-the-presidents-sham-executive-memorandum-is-doing-next-to-nothing-congress-must-reinstate-the-600/

Last week 1.4 million workers applied for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. Breaking that down: 892,000 applied for regular state unemployment insurance (not seasonally adjusted), and 543,000 applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). Some headlines this morning are saying there were 1.1 million UI claims last week, but that's not the right number to use. For one thing, it ignores PUA, the federal program that is serving millions of workers who are not eligible for regular UI, like the self-employed. It also uses seasonally adjusted data, which is distorted right now because of the way Department of Labor (DOL) does seasonal adjustments.

Republicans in the Senate allowed the across-the-board $600 increase in weekly UI benefits to expire. Last week was the third week of unemployment in this pandemic for which recipients did not get the extra $600. That means people on UI are now are forced to get by on the meager benefits which are in place without the extra payment, which are typically around 40% of their pre-virus earnings. It goes without saying that most folks can't exist on 40% of prior earnings without experiencing a sharp drop in living standards and enormous pain.

Earlier this month, President Trump issued a sham of an executive memorandum. It was purported to give recipients an additional $300 in benefits. But in reality, even this drastically reduced benefit is only available to recipients in a handful of small states, and only for a few weeks. The executive memorandum is a false promise that actually does more harm than good because it diverts attention from the desperate need for the real relief that can only come through legislation.

This is cruel, and terrible economics. The extra $600 was supporting a huge amount of spending by people who now have to make drastic cuts. The spending made possible by the $600 was supporting 5.1 million jobs. Cutting that $600 means cutting those jobs—it means the workers who were providing the goods and services that UI recipients were spending that $600 on lose their jobs. The map in Figure B of this blog post shows many jobs will be lost by state now that the $600 unemployment benefit has been allowed to expire. We remain 12.9 million jobs below where we were before the virus hit, and the unemployment rate is higher than it ever was during the Great Recession. Now isn't the time to cut benefits that support jobs.

Last week was the 22nd week in a row that initial unemployment claims were far greater than the worst week of the Great Recession. If you restrict this comparison just to regular state claims—because we didn't have PUA in the Great Recession—last week was the 22nd week in a row that initial claims have been greater than the second-worst week of the Great Recession. Initial claims rose last week, but ticked down in the prior two weeks. Some are wondering if that decline was a result of the $600 running out. The answer to that is an emphatic no. Though initial claims remain at extremely high levels, they have been fairly steadily dropping since their peak in early April, and what has happened since the $600 expired is just a continuation of those trends.

In other words, the $600 was not the reason people were applying for unemployment insurance—it is not what was keeping people out of work. In fact, rigorous empirical studies show that any theoretical work disincentive effect of the $600 was so minor that it could not even be detected. For example, a study by Yale economists found no evidence that recipients of more generous benefits were less likely to return to work, which is what we would expect to see if the extra payments really were a disincentive to work. And a case in point: in May/June/July—with the $600 in place—9.3 million people went back to work, and a large share of likely UI recipients who returned to work were making more on UI than their prior wage, but that did not stop them from going back. Further, there are 11.2 million moreunemployed workers than job openings, meaning millions will remain jobless no matter what they do. Slashing the $600 cannot incentivize people to get jobs that are not there. Even further, many people are simply unable to take a job right now because it's not safe for them or their family, or because they have care responsibilities as a result of the virus. Slashing the $600 cannot incentivize them to get jobs, it is just causing hardship.

Slashing the $600 is also exacerbating racial inequality. Due to the impact of historic and current systemic racism, Black and brown communities are suffering more from this pandemic, and have less wealth to fall back on. They are taking a much bigger hit with the expiration of the $600. This is particularly true for Black and brown women and their families, because in this recession, these women have seen the largest job losses of all.

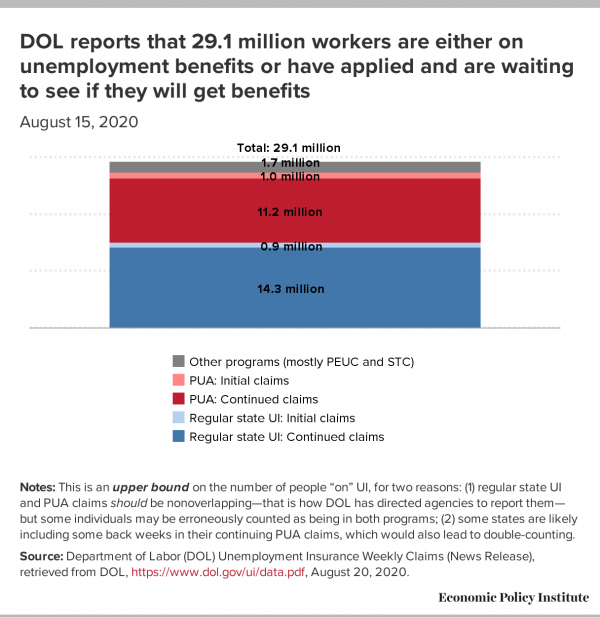

Figure A combines the most recent data on both continuing claims and initial claims to get a measure of the total number of people "on" unemployment benefits as of August 15. DOL numbers indicate that right now, 29.1 million workers are either on unemployment benefits, have been approved and are waiting for benefits, or have applied recently and are waiting to get approved. But importantly, Figure A provides an upper bound on the number of people "on" UI, for two reasons: (1) Some individuals may be being counted twice. Regular state UI and PUA claims should be non-overlapping—that is how DOL has directed state agencies to report them— but some individuals may be erroneously counted as being in both programs; (2) Some states are likely including some back weeks in their continuing PUA claims, which would also lead to double counting (the discussion around Figure 3 in this paper covers this issue well).

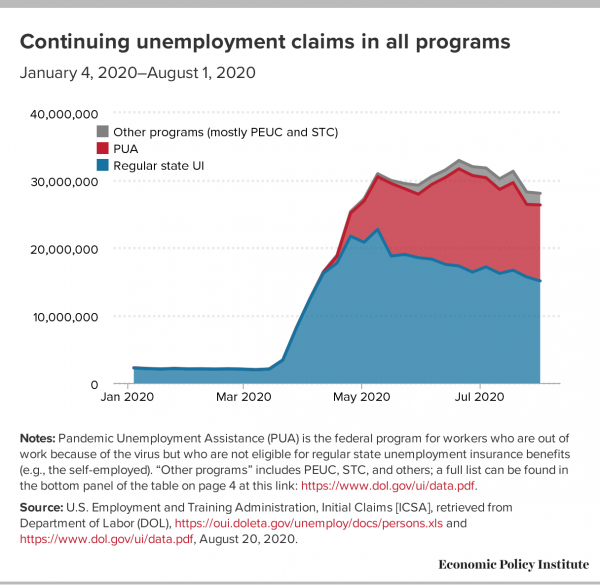

Figure B shows continuing claims in all programs over time (the latest data are for August 1). Continuing claims are more than 26 million above where they were a year ago. However, the above caveat about potential double counting applies here too, which means the trends over time should be interpreted with caution.

-- via my feedly newsfeed