https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2018/07/economy-of-intangibles.html

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Trade agreements and global production

Edith Laget, Alberto Osnago, Nadia Rocha, Michele Ruta 14 July 2018

Europe and North America are entangled in discussions to reverse or renegotiate existing trade agreements (Brexit, NAFTA), but other regions of the world are moving in the opposite direction. Examples include the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) between China, ASEAN countries and other regional partners, and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

An important question is how these agreements, made and unmade, will shape future trade and economic relations. Recent studies have investigated the effect of trade agreements on trade flows (Baier et al. 2017, Mattoo et al. 2017). In our research (Laget et al. 2018), we use new data on the content of trade agreements to assess their effects on countries' participation in global value chains (GVCs).1

Preferential trade agreements (PTAs) have become deeper over time, often going beyond traditional trade policy to encompass areas such as investment, competition, and intellectual property rights protection. To estimate the relationship between cross-border production linkages and the depth of trade agreements, we use a structural gravity model at the aggregate and sectoral levels. PTA depth measures are based on the new World Bank dataset on the content of PTAs, which covers 260 agreements signed by around 180 countries between 1958 and 2015 (Hofmann et al. 2018). This is the entire realm of PTAs in force and notified to the WTO as of December 2015.

Cross-border production linkages are measured in two ways:

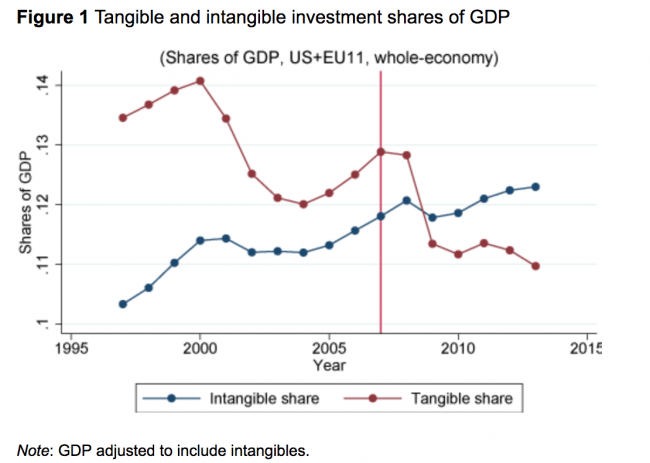

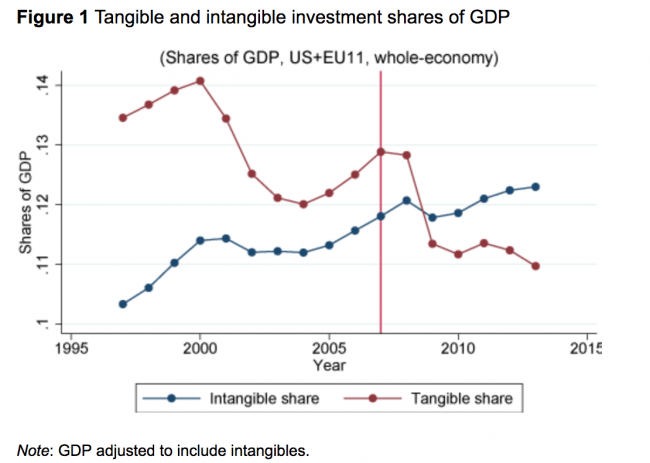

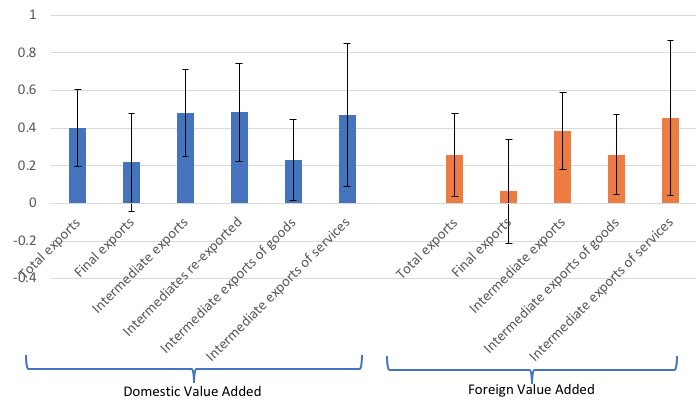

Using value added trade data, we find that deep PTAs increase the domestic value-added content of exports, mainly through global value chains. Figure 1 shows that adding a provision to a PTA boosts domestic value added of intermediate goods and services exports (in other words, forward GVC linkages) by 0.48%, while an additional provision in a PTA increases foreign value added of intermediate goods and services exports (backward GVC linkages) by 0.38%. We also find evidence that deep trade agreements improve forward linkages particularly for more complex GVCs, that is, GVCs for which exported intermediates cross borders two times or more. We do not find a significant impact of deep trade agreements on domestic and foreign value added of final goods and services exports. We make separate estimations for services and goods to show that the impact of deep trade agreements is usually higher for value-added trade in services than value-added trade in goods.

Figure 1 Effect of deep trade agreements on GVC integration

Source: Laget et al. (2018).

Notes: The estimator is PPML. All specifications include bilateral fixed effects and country-time fixed effects. The 90% confidence intervals are constructed using robust standard errors, clustered by country-pair.

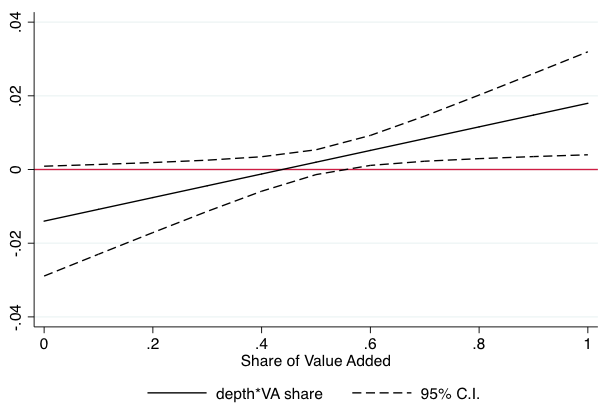

We also analyse whether the impact of deep trade agreements on GVC integration is heterogeneous across industries. Specifically, we estimate a set of sectoral regressions, including an interaction term between the depth of an agreement and the share of value added that a sector has in overall production. The results suggest that deep trade agreements are particularly relevant for GVC integration in high value-added industries (Figure 2). Not surprisingly, these industries are usually services sectors, which are characterised by non-tangible activities such as research and development or retail services that have high value added.

Figure 2 Marginal effect of additional provision in terms of average share of value added

Source: Laget et al. (2018).

Finally, we focus on the larger sample of country data available for trade in parts and components to empirically explore whether the impact of different provisions is heterogeneous across countries with different levels of development. We split the provisions covered in PTAs into two categories, depending on their relationship with WTO rules (Horn et al. 2010).

'WTO plus' provisions fall under the current mandate of the WTO (for example, tariffs and customs) and are already subject to some form of commitment in WTO agreements. 'WTO extra' provisions, on the contrary, refer to policy obligations outside the current mandate of the WTO (for example, investment, competition). The estimates suggest that WTO extra provisions are particularly important for GVC-related trade between North and South countries. On the other hand, WTO plus provisions are still relevant for trade among developing countries (South-South agreements).

Since the early 1990s, governments have signed progressively deeper trade agreements, and firms have fragmented production internationally. Our research finds that the deepening of the trade arrangements has been a key factor in the rise of global value chains. It has also helped countries to integrate in industries with higher values of production. These results indicate that the reshaping of international trade policy relationships we are observing today may have far-reaching consequences for the organisation of production in the future.

Baier, S, Y Yotov, T Zylkin (2017), "One size does not fit all: On the heterogeneous impact of free trade agreements", VoxEU, 28 April.

Dhingra, S, R Freeman, E Mavroeidi (2018), "Beyond tariff reductions: The effect of deep provisions on gross and value-added trade", VoxEU, 30 March.

Hofmann, C, A Osnago, M Ruta (2018), "The Content of Preferential Trade Agreements", forthcoming, World Trade Review.

Horn, H, P C Mavroidis, and A Sapir (2010), "Beyond the WTO? An Anatomy of EU and US Preferential Trade Agreements", The World Economy 33: 1565-1588.

Laget, E, A Osnago, N Rocha, M Ruta, (2018), "Deep Trade Agreements and Global Value Chains", World Bank policy research working paper 8491.

Mattoo, A, A Mulabdic, M Ruta (2017), "Deep Trade Agreements As Public Goods", VoxEU, 12 October.

Mulabdic, A, A Osnago, M Ruta (2017), "Trading off a 'soft' and 'hard' Brexit", VoxEU, 23 January.

[1] See also the related works by Mulabdic et al. (2017) and Swati et al. (2018) that discuss how Brexit will affect UK value chains under different post-Brexit trade arrangements.

|

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.