Saturday, February 24, 2018

Manchin wades into WV teacher walkout

Friday, February 23, 2018

Repost: Larry Summers: Here’s what Bernie Sanders gets wrong – and right – about the Fed

By Lawrence H. Summers December 29, 2015

U.S. Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders recently wrote an op-ed in the New York Times on financial reform. REUTERS/Chris Keane

Lawrence H. Summers, the Charles W. Eliot university professor at Harvard, is a former treasury secretary and director of the National Economic Council in the White House. He is writing occasional posts, to be featured on Wonkblog, about issues of national and international economics and policymaking.

Sen. Bernie Sanders had an op-ed in the New York Times on Federal Reserve reform last week that provides an opportunity to reflect on the Fed and financial reform more generally. I think that Sanders is right in his central point that financial policy is overly influenced by financial interests to its detriment and that it is essential that this be repaired. At the same time, reform requires careful reflection if it is not to be counterproductive. And it is important in approaching issues of reform not to give ammunition to right-wing critics of the Fed who would deny it the capacity to engage in the kind of crisis responses that, judged in their totality, have been successful in responding to the financial crisis. The most important policy priority with respect to the Fed is protecting it from stone-age monetary ideas like a return to the gold standard, or turning policymaking over to a formula, or removing the dual-mandate commanding the Fed to worry about unemployment as well as inflation.

Sanders is right that Fed governance has been and is overly tied up with the financial sector. Each of the 12 regional Feds has a board of directors that is made up of nine people — three banking representatives, three private-sector non-banking representatives and three public interest representatives. The fact that a member of Goldman Sachs's board at the time of the 2008 crisis was the "public interest" chairman of the New York Fed board is, to put it mildly, indefensible.

More generally, it is not clear why a government institution with vital policy responsibilities should have a role in governance for the private sector. Yes, advice on market conditions and the like is needed, but this can be sought from advisory committees. Yes, the Dodd Frank financial reform legislation did clean things up some by removing bankers from the selection process for regional bank presidents and orienting regulatory responsibility toward the Washington. But it is hard to imagine an appropriate governance activity for business figures with respect to the Federal Reserve System. Nor is it clear why banks should in any sense be "shareholders" in the Federal Reserve System.

I am less certain as to whether Sanders's particular reform of making regional presidents Senate confirmed is wise given the dysfunctionalities of the Senate process. Also, I suspect that this reform would strengthen the New York Fed with its close ties to Wall Street and hawkish regional presidents in ways that Sanders would not like.

A separate issue from Sanders's concern with governance is his concern with who holds the full-time senior positions within the Fed. He asks rhetorically whether the chief executive of Exxon should be head of the Environmental Protection Agency or the Federal Communications Commission should be stuffed with former Verizon executives. This is a difficult issue. There is a tension between acquiring expertise and avoiding co-optation or cognitive capture. In fact, many FCC chairs have had industry backgrounds, including both Obama FCC chairs who pushed net neutrality approaches that industry loathed. It would be a valuable study, but it is not my impression that, as a general matter, officials who come from industry have been systematically softer on industry than those who have come from other backgrounds. It is worth pondering that figures much respected for their commitment to aggressive financial regulation like Arthur Levitt came into their positions from full-time roles in industry, whereas the principal regulators in place before the 2008 crisis — Ben Bernanke, Tim Geithner, Christopher Cox — came from public sector backgrounds. Franklin Roosevelt was hardly a pushover to the financial industry. He famously made former stock-operator Joseph Kennedy the inaugural leader of the Securities and Exchange Commission on the theory that it takes a thief to catch a thief.

Sanders proposes to make the Fed more transparent and accountable by releasing not just minutes but transcripts six months after meetings rather than the current five years. I am not sure I understand the logic here. Monetary policy accountability is essential, but so is accountability for decisions of war and peace or protection of the environment. No one expects transcripts from the Pentagon's war room or the EPA senior staff meetings. The Supreme Court justices meet alone, without clerks or stenographers, because the best decisions tend to come when policymakers can deliberate privately before reaching conclusions. This encourages out of the box thinking and forceful dissent while minimizing grandstanding. Why should monetary policy be different? It seems to me that Janet Yellen has done great work over the years in pushing the Fed to be more open, and that if further steps are to be taken, they should be in the directions she has pioneered, such as more frequent press conferences.

With respect to proposals to audit the Fed, I think the issues are really of truth-in-labeling. There is no question that the Fed, like every other part of government, should be subject to independent audit. My understanding is that this is currently the case. If there are lacunae in current procedures, these should be pointed up and repaired. This is not the focus of current proposals, such as those of Ron Paul and Rand Paul, who would prefer to abolish the central bank and whose ideas are not so much about auditing the Fed as subjecting it to political control and straitjacketing it. Surely Sanders should not wish to curtail the Fed's ability to act with discretion to insure a continued flow of credit to businesses and households in the event of an economic downturn or financial crisis.

On the substance of monetary policy, I have been clearly on the dovish side of the Fed for quite some time and think the risks of the last rate increase exceeded the benefits. So I agree with Sanders's general thrust. I, however, prefer the "do not raise rates until you see the whites of inflation's eyes" to Sanders' rather arbitrary 4 percent unemployment target.

I did not feel strongly but am inclined to agree with Sanders that the Fed should not have paid interest in excess reserves while it was setting the Fed funds rate in the zero range. However, when rates are raised it is a matter of necessity that the Fed either pay interest on reserves or, what is essentially equivalent, offer Treasury bills to banks, which soak up their excess cash. In a positive interest rate environment, there is no way that banks will or should hold on to zero interest rate cash. I do not think there would be any expert support for Sanders views here.

On regulatory policy, no one is for gambling with insured deposits. But Sanders fails to recognize some of the tensions that make regulatory policy so difficult. Loans to small businesses — which he likes — are far riskier than holdings of securities that are marked-to-market on a daily basis. So if banks focused on traditional lending, they would be riskier than they are today. Indeed the majority of the world's banking crises — over the past three centuries and over the past quarter-century — have come from traditional lending, especially against real estate. Making banks safer means reducing their dependence on traditional lending activities. Balances must be struck.

Sanders asserts, as many do, that Glass Stegall's repeal contributed to the crisis. I may not be objective, as I supported this measure as Treasury Secretary, but I do not see a basis for this assertion. Virtually everything that contributed to the crisis was not affected by Glass Steagall even in its purest form. Think of pure investment banks Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, or the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, or the banks Washington Mutual and Wachovia or American International Group or the growth of the shadow banking system. Nor were the principle lending activities that got Citi and Bank of America in trouble implicated by Glass Stegall.

Moreover, preventing financial institutions from diversifying into multiple activities can actually make them more likely to fail. Imagine how much better the outcome would have been if Lehman had sold itself to a large bank during 2008. There is also the further point that without the repeal of Glass Stegall, it would have been much more difficult to aggressively use the discount window to contain panic following Lehman's fall.

We currently have a system in which institutions have higher capital requirements if they are larger, more complex or more interconnected. I think there is a good case to be made that capital requirements should be further increased and further graduated with size and complexity. This would tend to encourage deconsolidation and is I think the right 21st century response to the concerns about concentration in banking.

Finally, stepping back from Sanders specifics, I agree with his core claim that the excessive power of financial interests shapes financial policy to an unhealthy extent. I saw this during the debate on Dodd Frank when there were nearly five registered lobbyists for every member of Congress. It's worth pondering how policy would be different if special interests not were kept in check. Here are my top five:

First, the financial regulatory agencies would be adequately resourced and would not be under pressure to kowtow to legislators pushing their contributors interest. Commodity Futures Trading Commission head Tim Massad had it right when he condemned the recent budget agreement as undercutting the ability to regulate derivatives in a serious way.

Second, the Balkanized character of U.S. banking regulation is indefensible and would be ended. The worst regulatory idea of the 20th century—the dual banking system—persists into the 21st. The idea is that we have two systems — one regulated by the states and the Fed and the other regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency — so banks have choice. With ambitious regulators eager to expand their reach, the inevitable result is a race to the bottom.

Third, the current SEC and CFTC would be combined and charged with regulating in a coherent way all financial markets with respect to market integrity, manipulation issues, insider trading, transparency, fairness of execution, and systemic risk. When there were securities markets and commodity markets, it may have made sense. It no longer is defensible when the vast majority of "commodity trading" is in financial derivatives. The current system persists only so that multiple congressional committees can maintain jurisdiction over financial regulation and reap the benefits in terms of campaign contributions. Quite possibly, it would be a good idea to give the new agency if it was strong jurisdiction over fiduciary rules for investment and pension advisors.

Fourth, either the new agency formed out of the SEC and CFTC or the existing FSOC would take on systemic risks associated with asset management in a serious way. While the asset managers have the better side of the argument when they claim not to be systemic, in the sense of JP Morgan or Goldman Sachs, their activities are systemic and egregiously under regulated. It took far far too long to reach a still unsatisfactory solution with respect to money market funds. And ETFs are as likely as anything else to be the source of the next major bit of financial drama.

Fifth, there would be appropriate taxation of financial activities and the financial sector. Among the obvious reforms held back only by special interests are the highly preferential treatment of carried interest, the privileged treatment of dividends and capital gains, the ability of financial institutions to reduce their tax liabilities by using off shore tax havens and the tax deductibility of huge fines paid to resolve allegations of wrongdoing.

Senator Sanders is right that there is more to be done to respond to the long standing problems pointed up by the financial crisis, and he is right in his concern about the way in which special interests distort the process. These notes will have served their purpose if they help to channel legitimate energy in the most constructive directions.

--

Harpers Ferry, WV

Philip Ball: Chinese investment is paying off with serious advances in biotech, computing and space. Are they edging ahead of the west?

Chinese investment is paying off with serious advances in biotech, computing and space. Are they edging ahead of the west?

by Philip Ball

Fast forward four years to when, as an editor at Nature, I publish a paper on nanotechnology from world-leading chemists at the University of California at Berkeley. Among them was Xiaogang. That 1996 paper now appears in a 10-volume compendium of the all-time best of Nature papers being published in translation in China.

I watched Xiaogang go on to forge a solid career in the US, as in 2005 he became a tenured professor at the University of Arkansas. But when I recently had reason to get in touch with Xiaogang again, I discovered that he had moved back to China and is now at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou – one of the country's foremost academic institutions.

For Xiaogang, it seems that America was no longer the only land of opportunity. These days, Chinese scientists stand at least as good a chance of making a global impact on science from within China itself.

The economic rise of China has been accompanied by a waxing of its scientific prowess. In January, the United States National Science Foundation reported that the number of scientific publications from China in 2016 outnumbered those from the US for the first time: 426,000 versus 409,000. Sceptics might say that it's about quality, not quantity. But the patronising old idea that China, like the rest of east Asia, can imitate but not innovate is certainly false now. In several scientific fields, China is starting to set the pace for others to follow. On my tour of Chinese labs in 1992, only those I saw at the flagship Peking University looked comparable to what you might find at a good university in the west. Today the resources available to China's top scientists are enviable to many of their western counterparts. Whereas once the best Chinese scientists would pack their bags for greener pastures abroad, today it's common for Chinese postdoctoral researchers to get experience in a leading lab in the west and then head home where the Chinese government will help them set up a lab that will eclipse their western competitors.

There is always a certain fraction of talented, innovative people. China has the advantage of having lots of people

Many have been lured back by the Thousand Talents Plan, in which scientists aged under 55 (whether Chinese citizens or not) are given full-time positions at prestigious universities and institutes, with larger than normal salaries and resources. "Deng Xiaoping sent many Chinese students and scholars out of China to developed countries 30 to 40 years ago, and now it is time for them to come back," says George Fu Gao of the Institute of Microbiology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing – who himself gained a PhD at Oxford before studying at Harvard.

"The startup packages for researchers in good universities in China can be significantly higher than Hong Kong universities can offer," says Che Ting Chan, a physicist at the Hong Kong University of Science & Technology in what was previously China's affluent and westernised neighbour. "They provide more lab space and can help settle the spouse." That, he notes ruefully, "makes recruiting young faculty staff increasingly challenging here." Other well-off east Asian countries, such as Singapore and South Korea, are feeling the competition too.

The Chinese authorities are pursuing scientific dominance with systematic resolve. The annual expenditure on research and development in China increased from 1995 to 2013 by a factor of more than 30, and reached $234bn in 2016. The number of international publications coming out of China has remained in step with this rise. "Money is plentiful to certain Chinese researchers, possibly more so than to their competitors, especially if it means gaining an edge," says stem-cell biologist Robin Lovell-Badge of the Francis Crick Institute in London.

The ultimate aim is to develop a homegrown, innovative research environment, says Mu-Ming Poo of the Institute of Neuroscience of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai. "The government is beginning to recognise that big investment and recruitment of talent from abroad are not sufficient. We need to build infrastructure and mechanisms that facilitate innovation within China." That's not easy, and won't happen fast. "Officially, government leaders say that taking risks is allowed, but the system of evaluating scientists and projects, and the philosophy and methods of instruction in university curricula, aren't compatible with this policy."

China's strength also comes down to sheer numbers, though. "There is always a certain fraction of talented people who are innovative," says Chan. "China has the advantage of having a lot of people."

One of the more controversial ways Chinese institutions encourage their researchers to publish high-profile papers is to offer cash incentives. One study found that on average a paper in Nature or Science could earn the author a bonus of almost $44,000 in 2016. The highest prize on offer was as much as $165,000 for a single paper, up to 20 times a typical university professor's annual salary.

According to quantum physicist Jian-Wei Pan of the University of Science and Technology in Hefei, as a relative latecomer to the global scientific stage, China needs such incentives as a way of maintaining enthusiasm. Chan adds that "the rewarding system is transparent, and the expectation of the senior administration is clearly spelled out. Most of my friends in China don't see this as a problem – many feel that any formula, even if it's simple and naive, is better than no formula."

But could it not tempt researchers to cheat – fabricate or cherrypick results so that they can claim a dramatic discovery? The 2016 study of cash incentives also reported a rise in plagiarism, ghostwritten papers and other dishonest attempts to get published. Poo says that, whatever the case, the practice of cash incentives is not widespread. "Only a few low-level research institutions are doing this, not the Chinese Academy of Sciences or top universities," he says. He thinks that problems with scientific misconduct and fraud in China have more to do with poor quality control or lack of punitive measures.

However, the pattern seems clear, and is worth heeding by other nations: despite China's reputation for authoritarian and hierarchical rule, in science the approach seems to be to ensure that top researchers are well supported with funding and resources, and then to leave them to get on with it.s

Cloning, embryology and virology

The recent news that a laboratory in Shanghai has succeeded in cloning macaque monkeys made world headlines not just because of the impressive scientific feat but because of the implications for humans. While mammals from sheep (Dolly in 1997) to pigs, dogs and cows have been cloned before, primates have been a problem. Mu-Ming Poo and his colleagues cracked the problem by treating the monkey eggs into which the genetic material of the cloned individual had been placed with a cocktail of molecules that awaken the genes needed to promote development into an embryo. The Chinese team has so far only produced healthy baby monkeys by cloning cells taken from other monkey foetuses, not from adult monkeys. But Poo tells me: "I think cloning using adult cells will be accomplished soon, probably within one year."

Such experiments on our close evolutionary relatives raise ethical concerns, all the more so because there were many failures: only two live births out of 79 attempts. Nonetheless, the work makes human reproductive cloning look more feasible in principle. And despite the ethical issues surrounding such research (many countries ban it, including the UK), the magnitude and cost of the work already undertaken reinforces a sense that if China sets its sights on a particular scientific or technological target, nothing will get in its way.

It's with good reason Poo asserts that China has become a world leader in stem-cell science and regenerative medicine. Researchers at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou created similar surprise and alarm when in 2015 they announced the first use of high-precision gene-editing in a human embryo – not for reproductive medicine but to examine the viability of the technique to edit a disease-causing gene variant, using IVF embryos that could not develop further. That work was refused publication in the leading journals Nature and Science on ethical grounds, although related work has now been licensed and conducted in the UK. "Genome biology has been well supported in China for some time, with huge investment in genome sequencing projects," says Lovell-Badge.

There's perhaps a temptation to ascribe some of China's dominance here to a looser regulatory environment, but Lovell-Badge says that may not be the case. "Work on pigs and macaques is much easier and cheaper to do in China than in Europe and the US – it's not necessarily anything to do with animal research ethics," he says. "The best scientists want their work to be accepted in the west, so many have been trained by western scientists and their facilities designed with guidance from the west. But it is wrong to say that there are no restrictions. There may not be strict laws or even regulations, but there are strict guidelines – and if these are not followed, the consequences can be severe to the scientists involved."

China is taking great strides in other areas of biological science too. The waves of deadly bird flu that have afflicted the country annually since it was first detected in 2013 supply a very urgent need for research in virology. Chinese researchers had already learnt a lot about viral epidemics, says George Gao, after the outbreak of the particularly virulent form of influenza that caused SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) in 2002-3, originating in Guangzhou.

Gao's work has focused on understanding how 'zoonotic' viruses like bird flu, which cross from animals to humans, are transmitted across species. He has also looked at the structures and molecular mechanisms of the SARS, Ebola, Zika and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) viruses, all of which potentially pose global threats. The government has invested heavily in this field, he says, but he has no illusions that China still has some catching up to do. "In my opinion we are yet far behind US science in general. And we need a better system to encourage businesses to develop basic research."

The quantum internet

In January, Chinese researchers announced that they had sent data securely encrypted using the rules of quantum mechanics via satellite to Vienna in Austria – a demonstration of the potential of a "quantum internet" that Dutch quantum physicist Ronald Hanson of the Technical University of Delft describes to me as "a milestone towards future quantum networks".

Quantum information technologies harness the counterintuitive principles of quantum physics to do things with information that are impossible with the 1s and 0s of binary code in today's devices. Quantum computers can, for some tasks, operate faster and with more computational resources than ordinary computers, while a quantum telecommunications network – the quantum internet – could employ data-encryption methods that are rendered tamper-proof by the fundamental quantum laws of nature. The principles of so-called quantum cryptography were worked out in the 1980s, but applying them to information encoded in light signals for long-distance transmission is an immense technical challenge.

China's approach here again exemplifies its can-do mentality. The government has begun to install a fibre-optic network for quantum telecommunication stretching from Shanghai to Beijing. But for longer-distance transmission optical fibres are no good because the light signal eventually gets too dim as it passes along the fibre. Instead signals must be through the air, using lasers to connect orbiting satellites with ground stations. In 2016 China initiated an international project called Quantum Experiments at Space Scale (Quess) and launched a satellite designed for quantum data handling, called Micius after the romanised name of the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi.

The satellite work is being led by Jian-Wei Pan, who studied for his PhD in Vienna under Anton Zeilinger, one of the foremost scientists in the field of quantum information science. With that pedigree, Pan could have had his pick of jobs in the field, but in 2001 he chose to return to China. In 2009 he oversaw the task of constructing a "quantum communication hotline" for the military parade on the 60th anniversary of the Chinese communist state, and in 2012 he won the prestigious biennial International Quantum Communication award.

Pan's success in getting this technology up and running feels almost inexorable. Last year his team in Hefei drew more hyperventilating headlines by demonstrating the first "teleportation" of quantum objects (photons or "particles" of light) from the ground-based observatory at Ngari in Tibet to Micius, up to 1,400km away. The feat is not quite as science-fictional as it sounds – quantum teleportation, unlike the Star Trek version, does not involve any transmission of matter – but it could be an important trick for quantum telecommunications. The team also reported transmission of the "key" used for quantum encryption of signals between ground stations in China and Micius.

The latest advance was to get such keys all the way from Beijing to Vienna. This meant sending a laser signal with the quantum information from the Xinglong observatory near Beijing to Micius as it passed over China, and then having Micius communicate another such message with a station in Graz as it traversed the night sky over Austria. The link-up between Xinglong and Beijing, and between Graz and Vienna, was made along local fibre-optic networks. In this way, a video conference held between the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and the Austrian Academy of Sciences (of which Zeilinger is president) in Vienna was conducted with the robust security of quantum encryption – a striking harbinger of what a quantum internet might provide.

Pan says that the key to the remarkable success of Quess so far is coordination and collaboration within the immense pool of talent that China possesses. "When researchers [in different disciplines] undertake joint research, they can truly innovate,", he says.

Acquiring skills abroad is still important for Chinese researchers, says Pan, and will be for some time. But increasingly it's working the other way around too. "In my laboratory there are quite a few foreign students from developed countries, and some of them are even learning Chinese", he says.

Space

In China no goal seems too big – not even the sky is the limit. In June the Chinese space agency plans to launch a lunar space mission to deliver a satellite that will guide a rocket in 2019 to the far ("dark") side of the moon, bearing a robotic lander vehicle. The satellite link is essential for relaying data from the rover back to Earth. It's all part of a campaign aiming at a manned moon mission in the 2030s. China is already regarded as a serious contender with the US, Europe and Russia for predominance in space, although so far it has shown enthusiasm for collaborating with Europe. It has launched two prototype unmanned space stations in its Tiangong programme, a prelude to Tiangong-3, which, if launched in the early 2020s, will support a crew of three – potentially including astronauts from other UN member nations. China has even discussed building a moon base with the European Space Agency.

Despite this apparently collaborative spirit, China's space ambitions evoke the pioneering maritime voyages of Zheng He in the 15th century, which some historians today regard as a way of asserting the "soft power" and heavenly rule of the Ming emperor. Nothing like Zheng He's "treasure ships" had ever been seen on the oceans before: they dwarfed the vessels in which Europeans like Vasco da Gama explored the world. Many are now wondering whether, in science and technology, those times are returning.

Harpers Ferry, WV

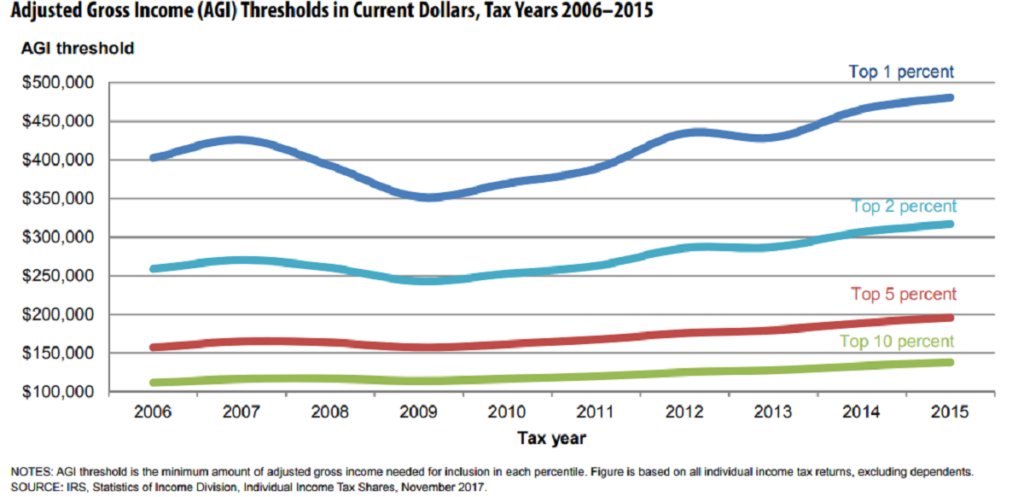

Top 1% = $480,930 (AGI) [feedly]

http://ritholtz.com/2018/02/get-1-need-adjusted-gross-income-480930/

click for ginormous graphic Source: Bloomberg This is quite intriguing: What does it take to get into the 1 percent? The price of admission is an adjusted gross income — basically, what you make before deductions — of $480,930. That's according to the latest Winter 2018 edition of the Internal Revenue Service's Statistics of Income Bulletin,…

The post Top 1% = $480,930 (AGI) appeared first on The Big Picture.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

The Economic Roots of the Rise of Trumpism

Harpers Ferry, WV

Dani Rodrik: What Does a True Populism Look Like? It Looks Like the New Deal

What Does a True Populism Look Like? It Looks Like the New Deal

By DANI RODRIK

President Trump's tough talk on trade and the tariffs he recently imposed on imported washing machines and solar panels, as well as the ones he threatened on foreign steel and aluminum, would seem straight out of the populist playbook. But in terms of targeting the real grievances of his popular base, they largely miss the mark.

The early history of American populism, culminating in the New Deal, suggests a more productive and less damaging kind of populism. When populism succeeds, it does so not by cosmetic gimmicks but by going after the roots of economic injustice directly.

At the 1896 Democratic National Convention, the 36-year-old former Nebraska congressman William Jennings Bryan delivered what became one of the most famous lines of American political oratory: "You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold." Bryan's immediate target was the gold standard, an emblem of the globalization of his day, which he blamed for the economic difficulties of what he called the "toiling masses." Bryan ran for president that year as the joint candidate of the Democratic Party and of the People's Party, also known as the Populist Party.

The populists of the late 19th century had many grievances, but the flames of their discontent were fanned by opposition to economic globalization. Under the gold standard, markets for money, goods, capital and labor had become intertwined among nations as never before. As John Maynard Keynes would later rue, a well-to-do inhabitant in a major capital city like London "could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth."

Global competition also drove American agricultural prices down. And the rules of the gold standard enforced tight money and credit conditions — what we would today call austerity policies. The consequent economic distress among farmers in the South and the West fueled the populist movement. The populists viewed the railroads as well as the financial and commercial interests of the Northeast, the defenders of the gold standard, as their main opponents. Throwing off the shackles of the gold standard and reclaiming national monetary sovereignty became their rallying cry.

Populism in the 21st century is as much a reaction to globalization as its late-19th-century version. While the backlash in the United States and Europe differs in specific details, the broad outlines are similar. Large segments of the workers in these advanced economies — older, less-skilled manufacturing employees and the communities they live in — have seen their earnings decline or stagnate and their relative social status take a big hit. These groups see governments as increasingly in the pocket of financial and business elites, the big winners of globalization. The discontent in turn fuels populist leaders who promise to wrest control from faceless global market forces and re-empower the nation-state.

The populist backlash unleashed by advanced stages of economic globalization should not have been a surprise, least of all to economists. The warning signs are right there in the basic economic theory we teach in the classroom. Yes, globalization expands economic opportunities: There are gains from trade. But globalization also entails stark distributional consequences, with some groups almost always left worse off. Factory closings, job displacement and offshoring are the flip side of the gains from trade.

Newsletter Sign U

What is more, these redistributive effects loom larger relative to the overall economic gains as globalization advances and trade agreements begin to aim at less consequential barriers. In other words, in its late stages, globalization looks less and less as if it is expanding the overall economic pie and more and more as though it is simply taking money from some groups and giving it to others.

In principle, an active government can take the edge off the resentment produced by redistribution. In Western Europe, an extensive welfare state has historically provided the safety nets that in turn enabled levels of economic openness that are much higher than in the United States. But often the response of the government has been to plead incapacity in the face of inexorable global economic realities: "We cannot tax the winners — the wealthy investors, financiers and skilled professionals — because they are footloose and they would move to other countries." This reinforces populists' yearning to reassert national economic control.

William Jennings Bryan ultimately failed in his quest for the presidency, and the People's Party imploded because of regional and ideological divisions. But many of the Populists' economic ideas, such as the progressive income tax, regulations on big business and much greater government control of the economy, were absorbed by the progressive movement and became part of the political mainstream.

It wasn't until 1933 that the Populists' main plank, the end of the gold standard, was adopted. By then the United States was mired in the Great Depression, and Franklin D. Roosevelt had decided the economy needed the monetary boost that adherence to the gold standard precluded. Internationalists complained that Roosevelt acted unilaterally, but he had little patience with orthodox economic ideas or shackles — foreign or domestic — on his conduct of economic policy. At home, he had to fight conservative courts to put his New Deal reforms in place.

By his day's standards, and perhaps also today's, Roosevelt was an economic populist. But the New Deal reinvigorated the market economy and saved capitalism from itself. It may also have saved democracy, as it helped staved off the dangerous demagogues and chauvinist ideologues, of which there were plenty (such as Father Coughlin and Huey Long).

The lesson of history is not only that globalization and the populist backlash are tightly linked. It is also that the bad kind of populism spawned by globalization may require a good kind of populism to fend it off.

President Trump and his European counterparts have capitalized on the economic difficulties of the middle and lower-middle classes by wrapping them in narratives that exploit prevailing ethno-nationalist prejudices. In the United States, they attribute declining wages and job prospects to Mexican immigrants, Chinese exporters and the federal government's preoccupation with minority groups at the expense of the white middle class. In Europe, they lay the blame for the erosion of the welfare state and public services on competition from immigrants and refugees. But none of this really helps the middle and lower-middle classes. Worse, the illiberal politics of the strategy undermines democracy.

If our economic rules empower corporations and financial interests excessively, then the correct response is to rewrite those rules — at home as well as abroad. If trade agreements serve mainly to reshuffle income to capital and corporations, the answer is to rebalance them to make them friendlier to labor and society at large. If governments feel themselves powerless to institute the tax policies and regulations needed to address the dislocations caused by economic and technological shocks, the solution is not just to seek more national autonomy but also to deploy it toward such reforms.

A populism of this kind can seem like a frontal attack on the economic sacred cows of the day — just as earlier waves of American populism were. But it is an honest populism that stands a chance of achieving its stated objectives, without harming fundamental democratic norms of tolerance and equal citizenship.--

Harpers Ferry, WV

Locking People Out of Medicaid Coverage Will Increase Uninsured, Harm Beneficiaries’ Health [feedly]

https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/locking-people-out-of-medicaid-coverage-will-increase-uninsured-harm-beneficiaries

State and federal policymakers have tried for several decades to make it easier for people to demonstrate their Medicaid eligibility by streamlining enrollment processes and limiting unnecessary requests for documents to verify eligibility. Kentucky's new Medicaid waiver and the extension of Indiana's current waiver mark a sharp reversal of these efforts: both erect multiple new barriers that can trip up eligible but unaware enrollees and lead them to lose coverage or even not apply in the first place if they think they aren't eligible.

-- via my feedly newsfeed

West Virginia GDP -- a Streamlit Version

A survey of West Virginia GDP by industrial sectors for 2022, with commentary This is content on the main page.

-

John Case has sent you a link to a blog: Blog: Eastern Panhandle Independent Community (EPIC) Radio Post: Are You Crazy? Reall...

-

---- Mylan's EpiPen profit was 60% higher than what the CEO told Congress // L.A. Times - Business Lawmakers were skeptical last...

-

via Bloomberg -- excerpted from "Balance of Power" email from David Westin. Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the late...