Is Economic Insecurity Behind the Specter of Populism?

A new study examines the role of the 2007–9 global financial crisis and its metastasis in Europe on voting and political beliefs, showing that crisis-driven economic insecurity is a substantial driver of populism and political distrust.

To paraphrase the opening line of the Communist Manifesto in 1848, a specter is haunting Europe and the West—the specter of populism. Populist parties and politicians have been gaining momentum all around the world over the recent years.

Nationalistic parties with an explicit anti-globalization—as well as anti-elite and anti-immigration agenda—have risen to power in Poland, Hungary, and Austria. AfD and Marine Le Pen's Front National did very well in the past German and French elections, respectively; and Beppe Grillo's Five Star Movement is leading the opinion polls in the forthcoming Italian elections. At the same time, radical left parties, opposing financial and trade globalization, have also been on the rise, especially in southern Europe with the electoral success of Syriza and Podemos. In 2016, Donald Trump's campaign was based on a typical populist anti-elite, anti-immigrant, and anti-trade agenda. Similarly, an anti-EU agenda was supported by the majority of British votes during the Brexit referendum. Populist parties and politicians are also on the rise in emerging and frontier economies. Furthermore, mainstream parties have taken note of the populists' successes and are now catering to people's growing demand for populist policies in many countries (Guiso et al. 2018).

A lot of ink has been spilled on the drivers of populism, mostly in the US and UK (Becker et al. 2018). Researchers, policy makers, and journalists seem to broadly agree that medium-term developments related to automation (technological progress and outsourcing) and rising competition in manufacturing from low-cost countries have hurt the middle class in advanced countries (as shown in a series of influential studies by Autor et al. 2016), which in turn is becoming attracted by the simplistic populist messages.

Rather than looking at medium-/long-run features, in recent work (Algan, Guriev, Papaioannou, and Passari 2017), we examine the role of the 2007–9 global financial crisis and its metastasis in Europe on voting and political beliefs in 220 subnational regions of 26 European countries. We show that crisis-driven economic insecurity is a substantial driver of populism and political distrust. We find a strong causal impact of the rises in unemployment on voting for non-mainstream, especially populist parties. Increases in unemployment go in tandem with a decline in trust in national and European political institutions.

Unemployment and Voting

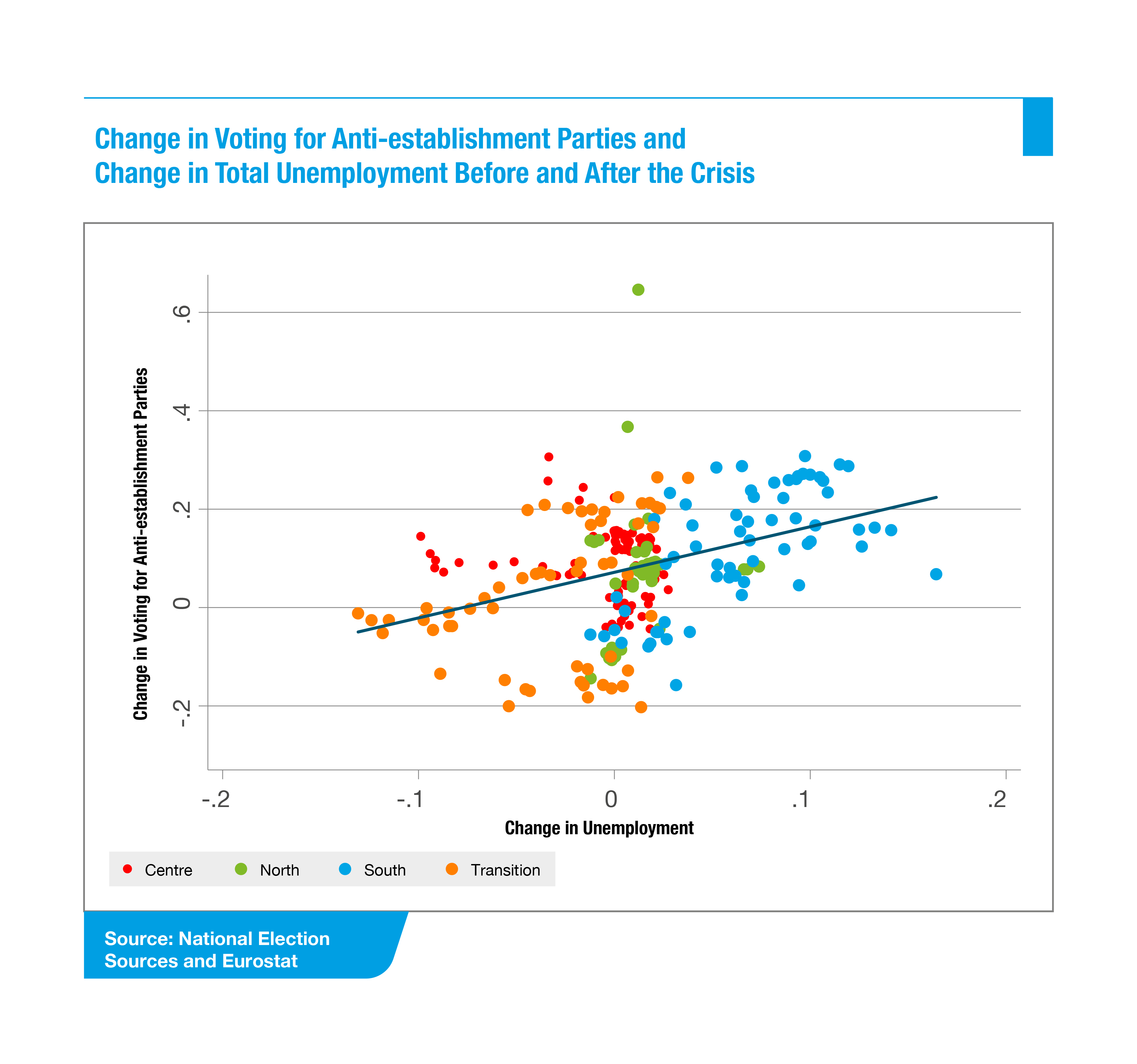

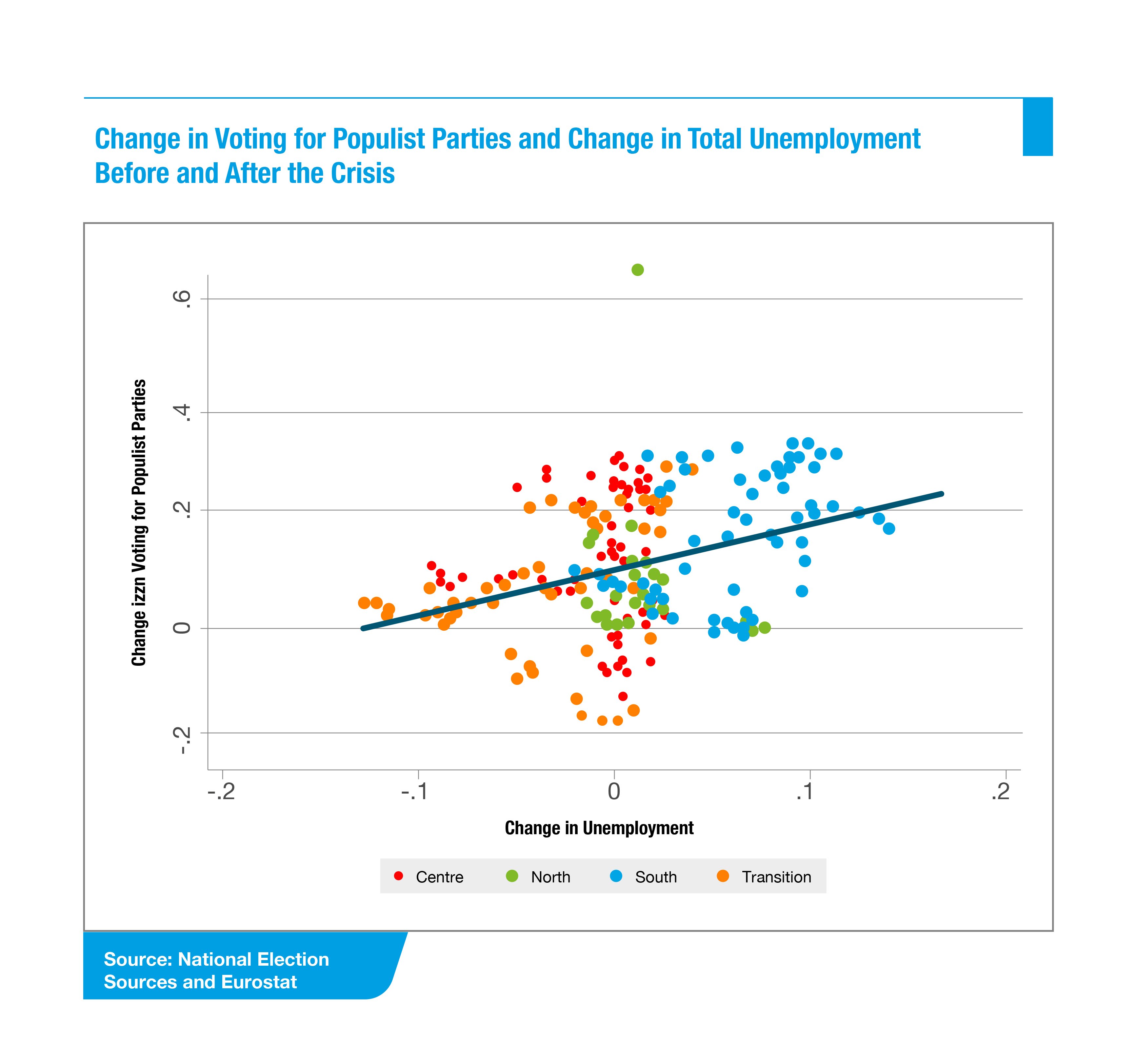

We assign non-mainstream parties into four (not mutually exclusive) categories using earlier works in political science and a reading of parties' manifestos: far-right nationalistic parties like the Golden Dawn in Greece or True Finns, extreme-radical left parties like Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain, populist parties like UKIP in the UK and the Five Star Movement in Italy, and Euro-sceptic like Jobbik in Hungary and Poland's Law and Justice party. As shown in Figures 1a and 1b there is a strong correlation between rising regional unemployment and voting for non-mainstream and especially populist parties. A one percentage point increase in unemployment is associated with a one percentage point increase in the populist vote. The association is especially strong in the south, where voters turn mostly to radical-left parties. In the north increases in regional unemployment are correlated with a rise in far-right party vote. This pattern is also present in eastern Europe, where people are moving towards xenophobic, anti-European parties.

These associations do not necessarily imply causality. To advance on causality we associate voting patterns to the component of changes in unemployment stemming from the pre-crisis share of construction (which is strongly related to falling unemployment pre-2007 and rising unemployment post-2008). This approach also yields a strong correlation between the recent rise of the populist vote and industrial specialization–driven unemployment.

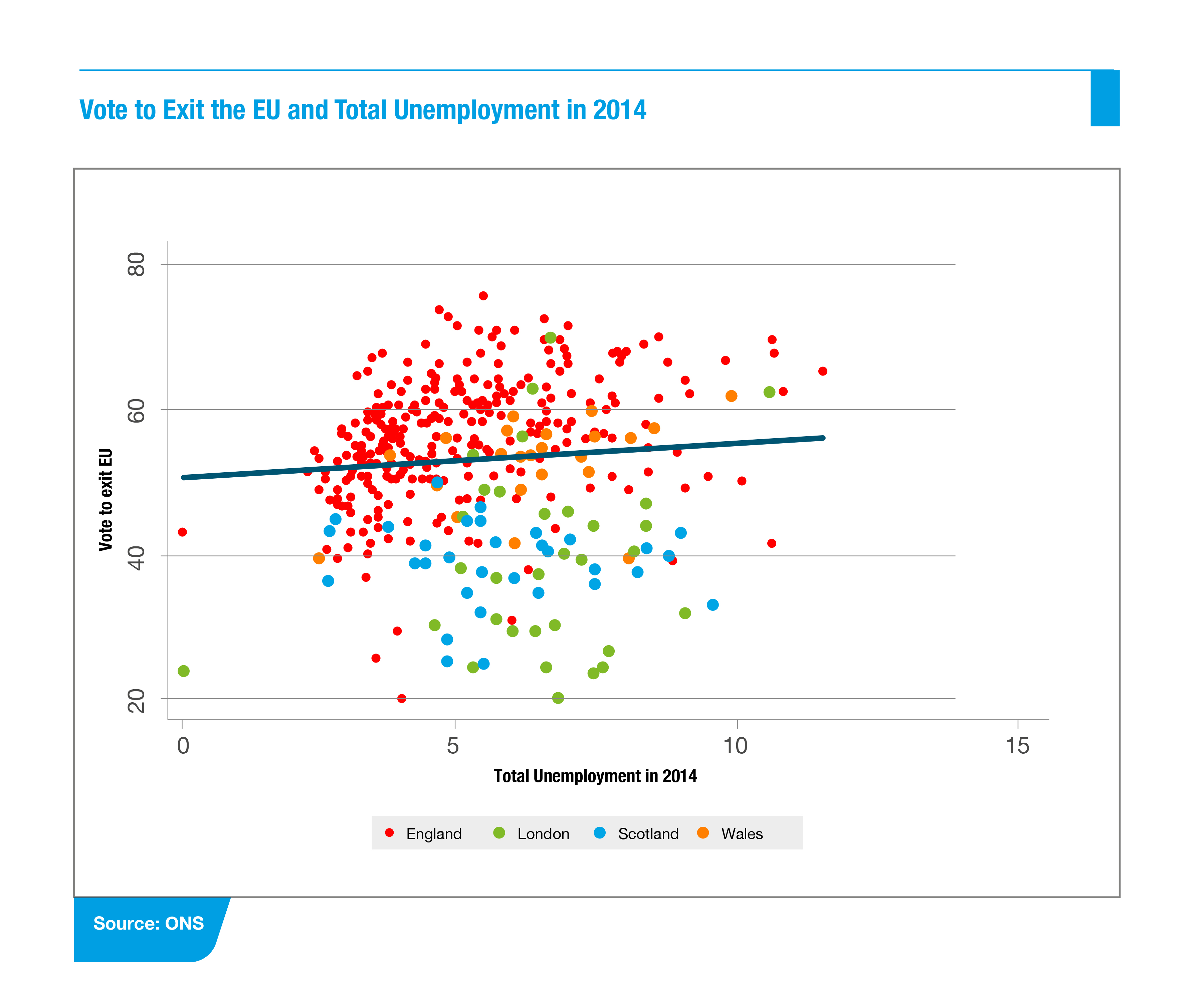

We then examine the role of the crisis on the Brexit vote across the UK's 379 electoral districts. In line with the European-wide results, Figures 2a and 2b show that the increases in regional unemployment before the referendum (2007–15) are strong predictors of the Brexit vote, while the level of unemployment is not much related to Brexit.

Unemployment and Political Beliefs

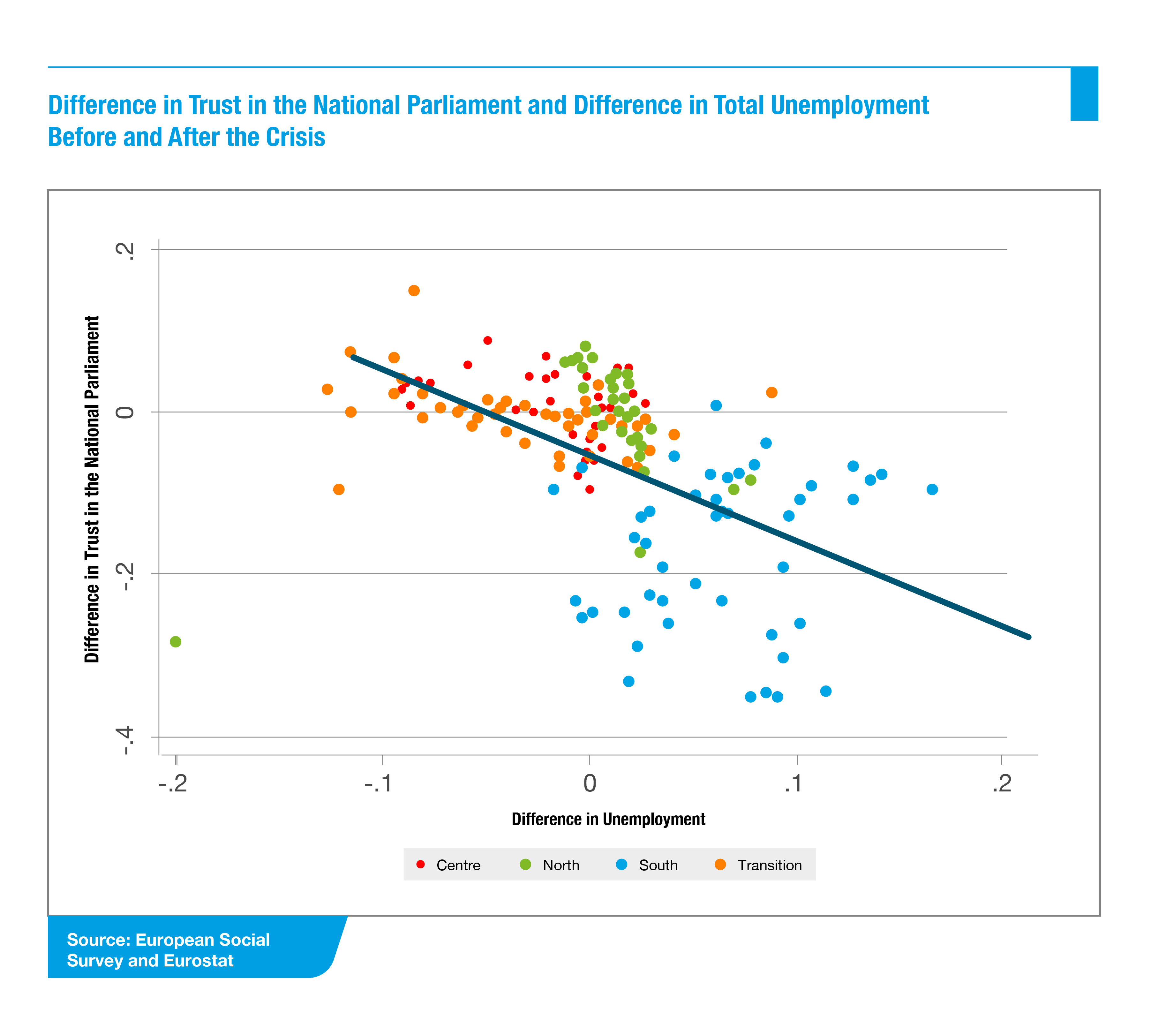

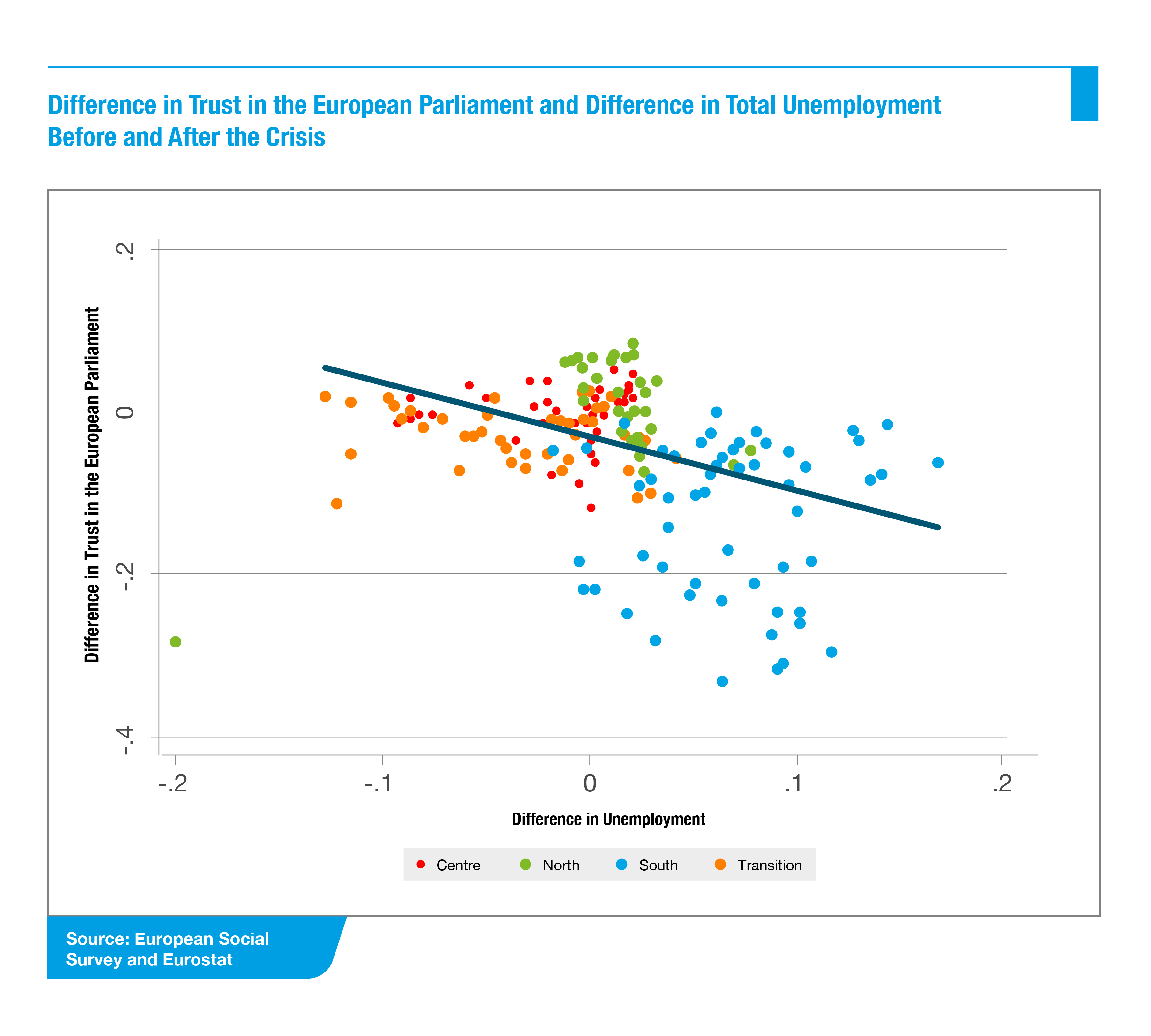

We then study the evolution of trust, political beliefs and attitudes before and after the 2007–10 crisis and examine whether swings in unemployment are related to changing ideology. We use individual-level data on Europeans' beliefs and attitudes from the European Social Survey that covers the period 2000–2014. Figures 3a and 3b show that increases in regional unemployment have resulted in a deterioration of trust towards national and European political institutions.

Unemployment is also related to declining trust in national courts, an alarming result as the rule of law is an essential element of Western democracies. Unemployment is not systematically linked to respondents' self-reported political orientation on the traditional left-right axis. This finding is thus in line with rising populism from both ends of the political spectrum. Although many new parties have emerged in Europe, respondents in crisis-hit areas are more likely to report that no party is close to their views. Finally, we uncover an interesting heterogeneity when examining the impact of unemployment on beliefs about the future of Europe. In the south (Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Cyprus) increases in unemployment are mapped with aspirations for deeper European integration. In contrast, in central and northern European countries (Germany, Netherlands, Austria), respondents in crisis-hit regions argue that the European Union project has gone too far.

These patterns apply to men and women, younger and older cohorts. The relationship between unemployment and distrust in national and European institutions is stronger for non-college graduates, a pattern that echoes the findings of Autor et al. (2016, 2017), Che et al. (2016), and Colantone and Stanig (2016), who relate populist voting and political polarization to depressed wages among unskilled workers fueled by rising competition from low-/middle-income countries.

Unemployment and Beliefs on Immigrants

Given the widespread anti-immigration rhetoric of Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Viktor Orban, and other populist politicians, we also examined the association between regional unemployment and self-reported beliefs on the role of immigrants in the society and the economy. Individuals in more crisis-hit regions are not more likely to express negative feelings about immigrants and their role in country's cultural and social life. There is some evidence that in regions that experienced the highest increase in unemployment respondents argue that immigrants' economic impact has been on average negative. Yet this association—though statistically significant—is not particularly strong.

However, when we examine heterogeneity we find that for non-college educated respondents the link between unemployment and negative feelings on immigrants' economic impact is sizable, most likely because unskilled workers have been affected the most from the crisis, technical progress, and globalization. Although unemployment is especially high among the youth and although the European social safety net is less strong for younger cohorts, attitudes towards immigrants among them have not moved much, most likely because of rising cosmopolitanism and open mindedness.

Implications

Our results give a rationale for countercyclical macroeconomic policies, preventing rising unemployment and attenuating its impact. Even a temporary increase in unemployment may result in political fallout, which in turn would give rise to anti-market policies undermining long-term growth. Indeed, a cyclical downturn may bring about populist policies which in turn can give rise to sustained negative economic implications.

The impact of rising unemployment on political trust is also important for the success of structural reforms that many European countries are currently implementing. Political trust is key for the reforms that are painful in the short run but deliver socioeconomic benefits later (such as labor market reforms, reforms of public administration, opening up protected occupations, deepening the fiscal and banking union). In order to support such reforms, the public needs to trust that politicians have the public interest at heart. If this is not the case, reforms are not implemented—or get reversed by populists. This in turn means that unemployment remains high, further reinforcing the vicious circle of political distrust and lack of reforms.

References

Algan, Yann; Sergei Guriev; Elias Papaioannou, and Evgenia Passari. (2017). "The European Trust Crisis and the Rise of Populism." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2018

Autor, David H., David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, and Kaveh Majlesi. (2016). "Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure." Working paper. MIT Department of Economics.

Autor, David H., David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, and Kaveh Majlesi. (2017). "A Note on the Effect of Rising Trade Exposure on the 2016 Presidential Elections" Working paper. MIT Department of Economics.

Becker, Sascha O., Thiemo Fetzer and Dennis Novy, (2017). "Who Voted for Brexit? A Comprehensive District-Level Analysis", Economic Policy, 32(1).

Che, Yi, Yi Lu, Justin R. Pierce, Peter K. Schott, and Zhigang Tao. (2016). "Does Trade Liberalization with China Influence US Elections?". No. w22178. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Colantone, Italo and Pierro Stanig (2016), "Global Competition and Brexit", BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 2016-44. Forthcoming American Political Science Review

Colantone, Italo, and Piero Stanig. (2017). "The Trade Origins of Economic Nationalism: Import Competition and Voting Behavior in Western Europe". Forthcoming American Journal of Political Science.

De Vries, Catherine E. (2017). "The Cosmopolitian-Parochial Divide: What the 2017 Dutch Election Result Tells Us About Political Change in the Netherlands and Beyond". Journal of European Public Policy, forthcoming.

Dustmann, Christian, Barry Eichengreen, Sebastian Otten, Andre Sapir, Guido Tabellini and Gylfi Zoega (2017), "Europe's Trust Deficit: Causes and Remedies", Monitoring International Integration 1, CEPR Press.

Guiso, Luigi, Helios Herrera, and Massimo Morelli. (2017). "Populism. Demand and Supply of Populism". Working Paper n°1703, Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF).

Disclaimer: The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.

Harpers Ferry, WV