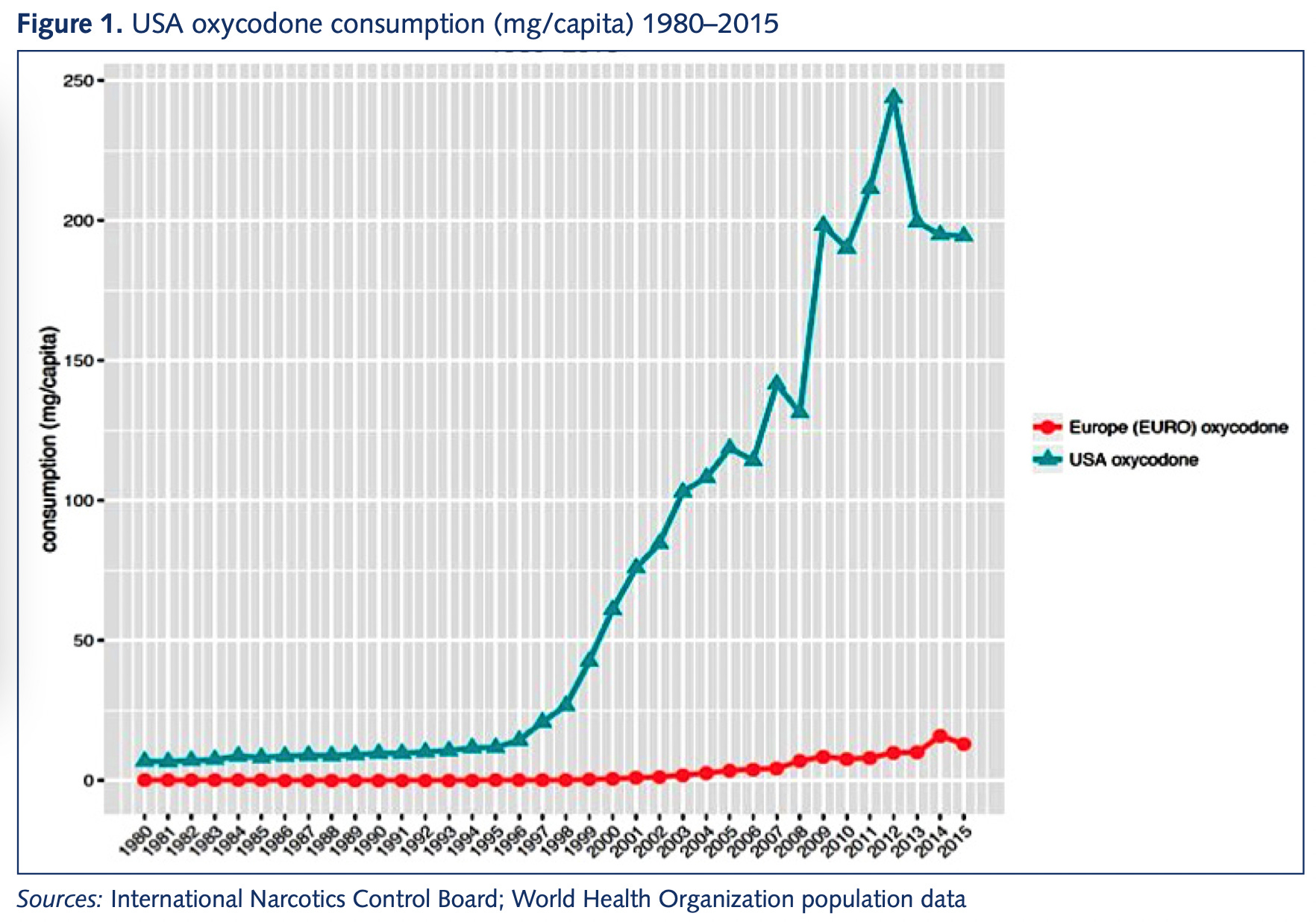

Overtreatment in American health care is a problemAn entrepreneurial, market-oriented system has some downsides.One of my tweets last week was, unlike most of my tweets, generally popular and well received by progressives. It made the point that one of the structural features of the American health care system is that it's a basic consumer business, which means giving people medicine that they don't really need can be very lucrative. Apparel companies want to sell you lots of clothing; American doctors and pharmaceutical companies want to sell you lots of treatment.  Matthew Yglesias @mattyglesias Matthew Yglesias @mattyglesiasApril 15th 2022 29 Retweets728 LikesTo the extent that I got pushback from the left, it was from people questioning whether the innovation is real (also here and here) or saying that innovation is all publicly funded anyway. I don't think that's correct. America's lack of price controls means that companies have a strong incentive to deliver new treatments here first. And the fat margins they can achieve in the U.S. market clearly drive more investment in treatments than in a more typical system. Reformers often say we could compensate with other pro-innovation policy ideas, and I totally buy that — we could. But if we just cut out the money, there really would be less innovation. And America's biomedical innovation is genuinely impressive. One of the mRNA vaccines against Covid-19 was developed by an American company and the other was a joint U.S.-German effort. Paxlovid, a highly effective and underutilized Covid-19 treatment, also comes from an American company. If a rich person in a poor country decides to fly somewhere to get some very expensive health care, the destination is typically the U.S. Our health care system has a lot of failings in terms of access for the poor, annoying bureaucracy, and creating financial insecurity for people with chronic ailments. It's also pretty obvious that health care is not actually the primary factor in population-level health, and that Americans suffer from unusually high rates of obesity, lethal violence, and car wrecks. That innovation is valuable, and any reforms should preserve that value. This is one reason I'm very interested in finding ways to make it cheaper and faster to do clinical research. But the overtreatment issue is real. And as economist Dean Baker says, that extends to treatments that don't work at all or are even harmful. Overprescription of opioids has caused a huge problemAs outlined in "Empire of Pain," America's devastatingly difficult opioid epidemic stems from profit-seeking pharmaceutical companies talking people into the idea that opioids are a useful treatment for chronic pain.  Dean Baker @DeanBaker13 Dean Baker @DeanBaker13April 15th 2022 1 Retweet69 LikesChronic pain is a very real problem. You can understand why people were strongly motivated to believe that a great new treatment option was available; it just wasn't true. But in America, there was a lot of money to be made off of accepting the pharmaceutical companies' claims. This was not the case in Europe, and that led to a significant divergence in prescription practices. And while it's easy to lay all of the blame on the Sacklers and the pharmaceutical industry, the doctors who do the prescribing deserve a share as well. In America's marketized, entrepreneurial health care system, a medical doctor is often also a small businessman whose job is to gin up business and drive sales. If a new product hits the market and 90 percent of the profession is cautious and responsible about its use, that's a chance for the other 10 percent to gain market share. The market for quacksOne of the most striking things about health care is that the profession of doctor existed long before there were any scientifically valid medical treatments. When George Washington got sick, he was treated by a panel of doctors who bled him to death. People didn't go see doctors as much back then as they do now, but there were plenty around — it was a distinguished and high-status field, even though practitioners had no idea what they were doing. Modern medicine is obviously a lot better than that, thankfully. But the same underlying dynamic still exists — there's plenty of money to be made selling supplements or "alternative" medicines that plainly don't work. When people are suffering, they will pay money for treatments whether or not there is solid evidence that the treatments are good for them. We also see a lot of this in the unregulated supplement market. A 2017 Consumer Reporters article says "Liver Damager from Supplements is on the Rise," echoing problems that I've seen reported on going back to 2012 and which have been the subject of continuing work in subsequent years. In 2019, Robert Fontana and Ammar Hassan, two liver doctors at the University of Michigan, reported on health risks associated with supplements:

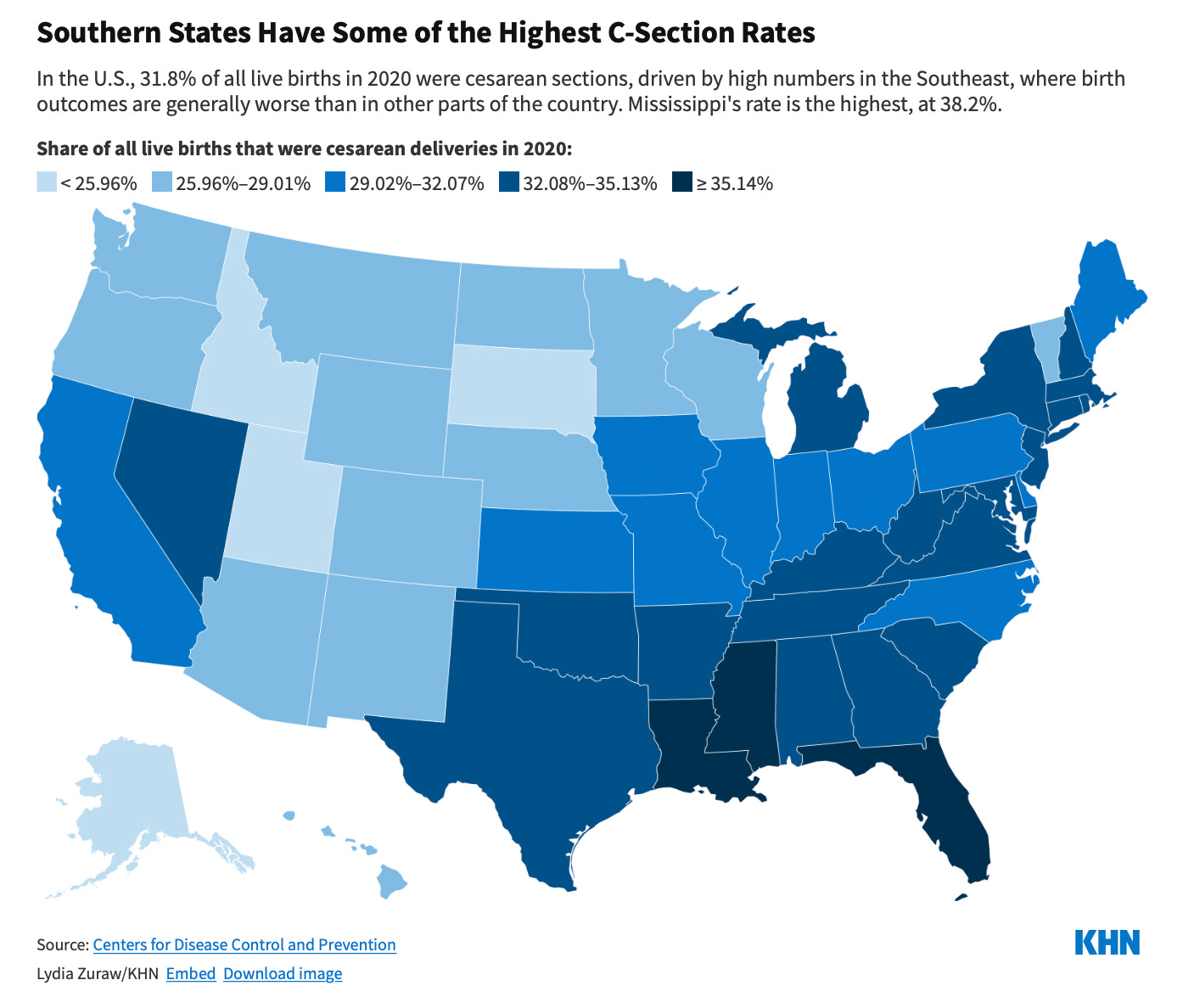

The dangers associated with overconsumption of steroids are pretty well known, but the authors note that overconsumption of green tea extracts also leads to liver damage. And while actual medicines are more tightly regulated, the FDA doesn't step in to prevent aggressive sellers with asymmetrical information from selling people treatments that may not be useful. Medical practice often isn't what it should beCaesarian sections save lives and have for a long time. A C-section is also a major surgical procedure that is difficult to recover from, especially because the patient also typically has to care for a newborn baby. So ideally, doctors would perform this surgery only when necessary, not just willy-nilly. Yet as Lauren Sausser writes for Kaiser Health News, the extreme regional variation in C-section rates prompts the suspicion that doctors in the high-rate areas are reaching for this option too aggressively. Sausser also notes some suspicious temporal patterns:

And as Gee explains, part of the issue is payments. A lot of states have their Medicaid programs structured so that from a doctor's point of view, a C-section is not only faster but more lucrative. You don't need to assume any cartoonish malfeasance on the part of providers to see how the objective structure of the incentives could bias their decision-making. At any rate, I'm not really saying anything new here. Everyone who writes and thinks about health care has been saying for years that America's system of rationing health care based on the ability to pay leads to overtreatment of some even while access is denied to others. Some recommended reading if you're interested:

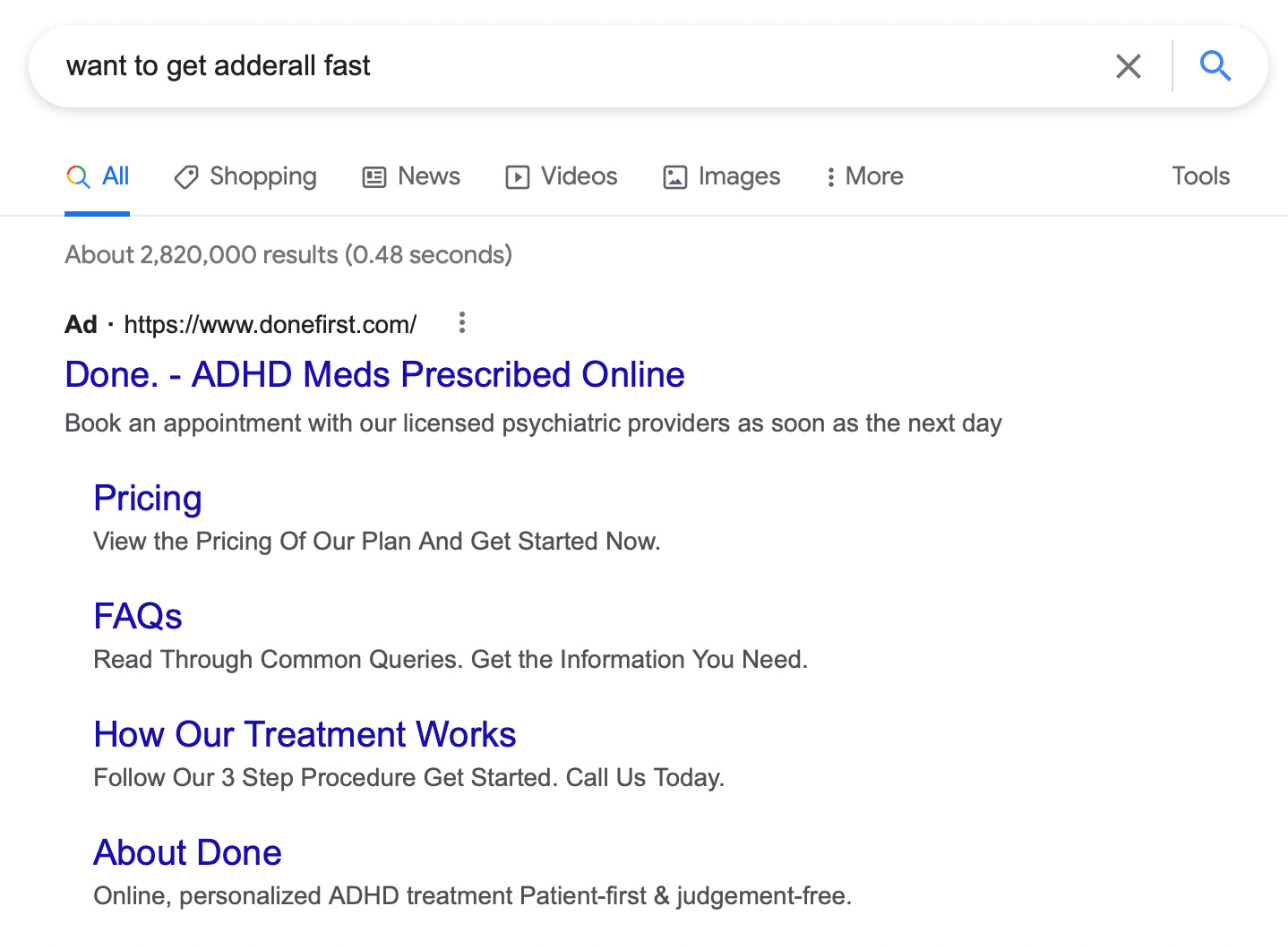

You can also find more academic treatments of the issue like "Overtreatment in the United States" with a team of authors in PLoS One from 2017. The BMJ has a "too much medicine" initiative. Indeed, the hypothesis that American medical professionals' income is inflated by billing for unnecessary care isn't even controversial among medical professionals. A 2017 Johns Hopkins survey of 2,000 physicians found the controversy is why (not whether) doctors are billing people for so much unnecessary care — survey responses indicated that "physicians believe overtreatment is common and mostly perpetuated by fear of malpractice, as well as patient demand and some profit motives." Obviously doctors like the malpractice theory because it is more flattering to them than the profit motive. But as Aaron Carroll details in this JAMA Forum, the malpractice concern is a minor factor at best. Malpractice laws vary from place to place, for example, but doctors don't tend to change their clinical practice when they move. Doctors are selling products to clients. As with anything else, your best case scenario is to have a product that's genuinely useful. But on the margin, your incentives are to sell aggressively — a pattern you see in any industry. A plot twistSo this is all pretty boring, conventional wisdom stuff. The problem of overtreatment has been widely discussed in the United States for years, and while there's plenty of disagreement and controversy about it, every significant institution I'm familiar with sees it as (1) a real phenomenon in general and (2) a plausible hypothesis for explaining specific trends. For example, if you say that ADHD is overdiagnosed or anti-depressants are overprescribed, people may argue with you about whether your claim is accurate, but the question itself is seen as a reasonable concern. And in particular, if I were to say not that ADHD is overdiagnosed in general, but that there are specific doctors who are known for handing out Adderall like candy, then I think it becomes totally uncontroversial (read my mentions here to see how little controversy this stirred up). Googling "want to get Adderall fast," you can even see people buying ads against that search term touting their "patient-first & judgement-free" approach to prescription stimulants. Where this kind of boring take is going to rocket to nuclear strength heat is that I was thinking about these long-running overtreatment issues when I read an article about the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria in Amsterdam. The clinic launched in the 1970s at a time when gender dysphoria treatment was rare and stigmatized. In the late-1980s, they first treated a 12-year-old and also developed the world's first protocols for treating trans teens. But over time, what was once seen as the most forward-looking and supportive clinic for gender-affirming health care has come to be seen as a hyper-cautious dinosaur compared to contemporary American gender clinics.

I think that if you tune out the culture war context in which this disagreement is situated, you have a specific instantiation of a general phenomenon here — the more entrepreneurial, market-oriented American health care system is more eager to make the sale — and there is a reasonable question as to whether an express lane to medication is in fact the right solution for public health. What's different is that if I said, "I'm concerned that some doctors are overprescribing Adderall," nobody would find that particularly interesting. Some might agree, others might disagree, but it wouldn't be a huge deal. The notion that nursing homes are over-using medication to address the needs of people in their care because that's faster and easier than labor-intensive interpersonal work is broadly accepted as fact. The culture war contextIn Texas, Greg Abbott and Ken Paxton have handed down directives to classify all medical treatment of transgender children as a form of child abuse. That seems obviously outrageous to me (note that de Vries' clinic has, to the best of my knowledge, an excellent track record of success with these treatments) and is also causing secondary problems as child protective services workers resign rather than enforce unjust laws, depriving Texas of the ability to investigate real child abuses. Florida, similarly, is moving to block all gender-affirming care for transgender youth which is a major overreach. I would in particular associate myself with this letter from Florida health care professionals that appeared in the Tampa Bay Times (emphasis added):

The way a lot of people approach the world is that when something bad is happening, as it is in Texas and Florida, they don't want any intra-coalition quibbling or infighting. So progressives see that Ron DeSantis claims to be acting in accordance with the Swedish, Finnish, etc. guidelines and then criticize him for lying and leave it at that. But the reason Florida cited those foreign guidelines is that it really is true that Sweden's National Board of Health and Welfare has adopted a more conservative approach to the use of puberty blockers than the current American standard, just as the Dutch clinic that pioneered gender-affirming youth care is more conservative than American clinics. And while the question of whether Texas and Florida have gone too far in restriction is important, so is the question of whether Sweden is right or American advocates are. And while I'm not certain about the answer to that question (though my guess is that Sweden is closer to the mark), I'm really certain that it is not currently getting the rigorous in-depth treatments that it deserves. |

Monday, May 2, 2022

Matthew Yglesias: Overtreatment in American health care is a problem

Friday, April 29, 2022

Dean Baker The Surge in Imports and the Drop in GDP

Many people were struck by the 1.4 percent drop in GDP in the first quarter, with some reports suggesting this was the beginning of a recession. This is not the real story of the first quarter GDP, instead it looks like growth is continuing at a healthy rate. To understand this point, it is important to recognize how imports are counted in GDP, since the increase in imports subtracted 2.53 percentage points from GDP growth in the quarter.[1]

Imagine that the sum of consumption spending, investment, and government spending increased at 2.7 percent annual rate in the quarter (which they did). Now suppose that we offloaded $60 billion of goods from boats sitting offshore, increasing our imports by this amount. On an annual basis, this additional $60 billion in imports would be $240 billion, or roughly 1.0 percent of GDP. This would reduce GDP by this amount, even though our purchases for consumption, investment, and the government had not changed.

Okay, that story is not exactly right. The goods that we offloaded from the ships are now sitting in warehouses at the ports or on their way to the retail outlets where they will eventually be sold. This increase in inventories would raise GDP by an amount equal to the growth in imports, offsetting the drag that imports otherwise would have been on growth. However, inventories were actually a drag on growth in the quarter, subtracting 0.84 percentage points from GDP.

These two facts can be reconciled by looking at the actual amount that inventories increased in the first quarter. The report showed that inventories increased at a $158.7 billion annual rate. (Non-farm inventories rose at an even more rapid $185.3 billion annual rate. Farm inventories shrank at a $35.8 billion rate, continuing a pattern that has been going on for sixteen years, but that is another story.)

This is an extremely fast pace of inventory accumulation. By comparison, in the years of 2016-2018, three normal years of economic growth, inventory accumulation averaged $45 billion. The reason inventories were a negative factor in growth in the first quarter, in spite of this extraordinary rate of accumulation, is that inventories grew at an even more rapid $193.2 billion annual rate in the fourth quarter of 2021. That rise added 5.32 percentage points to the fourth quarter's growth.

So how do we think about first quarter growth? It probably makes the most sense to focus on the measure of final demand to domestic purchasers, which rose at a very healthy 2.6 percent annual rate. This is measuring the growth in consumption, fixed investment, and government expenditures. If we want the fullest picture, we can combine the fourth quarter's 6.9 percent growth rate with the first quarter's 1.4 percent decline to get a 2.8 percent average growth rate for the last two quarters.

In addition to recognizing that the economy is still growing at very healthy pace, inventories have been largely rebuilt, in spite of supply chain problems. Real non-farm inventories at the end of the first quarter were just 0.1 percent below their pre-pandemic levels. (Farm inventories are now at just 53.0 percent of their level of 16 years ago.) This is a very positive sign, in that it should be mean that the prices of many items that rose sharply in the last year will be leveling off, and quite likely coming down.

In short, rather than being a bad report with a drop in GDP, this report is overwhelming good news. It shows that the main components of final demand, consumption, investment, and government expenditures, are growing at a healthy pace. And, it shows that inventories have been largely rebuilt, meaning that supply chain problems are being alleviated. Inflation is of course a problem, but this rise in inventories is exactly what we want to see if inflation is to be slowed.

[1] A drop in exports subtracted another 0.68 percentage points. This is likely also due to supply chain issues, as exporters can't arrange for shipping containers.

Monday, April 18, 2022

Understanding the economics of monopsony: How labor markets work under imperfect competition [feedly]

https://equitablegrowth.org/understanding-the-economics-of-monopsony-how-labor-markets-work-under-imperfect-competition/

-- via my feedly newsfeed

Contrary to what many of us were taught in Introduction to Economics courses in college and graduate school, markets are rarely perfectly competitive. In the case of the market for labor—a market that, it is worth noting, is fundamentally different from those where financial products or commodities are bought and sold—imperfect competition means that workers' pay is solely determined neither by their productivity nor by the forces of supply and demand.

In recent years, rising interest in the causes, consequences, and policy implications of imperfect competition has sparked a new wave of research on a framework known in economics as monopsony. Kate Bahn, the director of labor market policy and chief economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, defined monopsony in a briefing to congressional staffers last month: "Monopsony can be narrowly defined as any time there is one or few employers hiring workers, so they have considerable power to keep wages low since those workers do not have a lot of other options for jobs."

But monopsony power, Bahn noted, is present not just when there are only a few employers in a particular labor market. Barriers that limit workers' ability to move from job to job, incomplete or asymmetrical information about jobs, and discrimination are all factors that can give employers an upper hand when setting wages and, with it, the power to underpay workers.

Hosted by Equitable Growth on March 23, the briefing, part of a series dubbed "Econ 101," introduced Hill staffers to labor markets under monopsony. During the presentation, Bahn first discussed how the assumptions that underpin the view that markets are perfectly competitive are rarely met. She then described the basics of the monopsony model and covered some of the empirical evidence on how monopsony affects the U.S. workforce and economy. And to wrap up, Bahn discussed the public policies that can counteract employers' wage-setting power, boost competition, and deliver broadly shared economic growth.

The implications of monopsony for U.S. labor markets

So, what are the implications of monopsony for our understanding of how labor markets work? And what does imperfect competition mean for the design of effective and equitable economic policy?

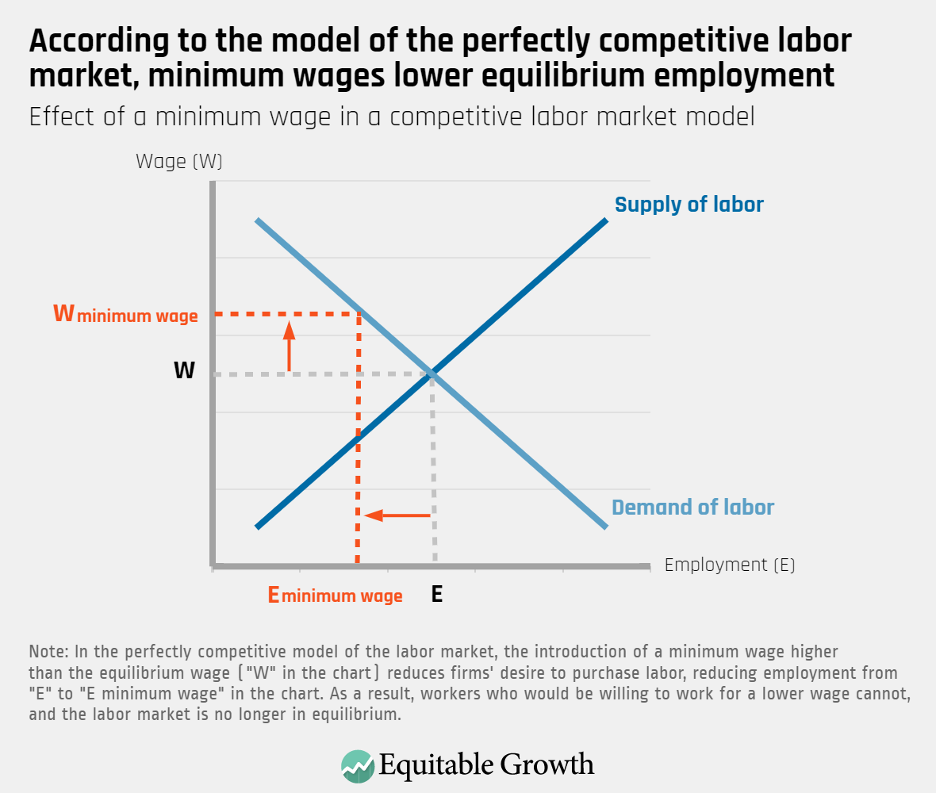

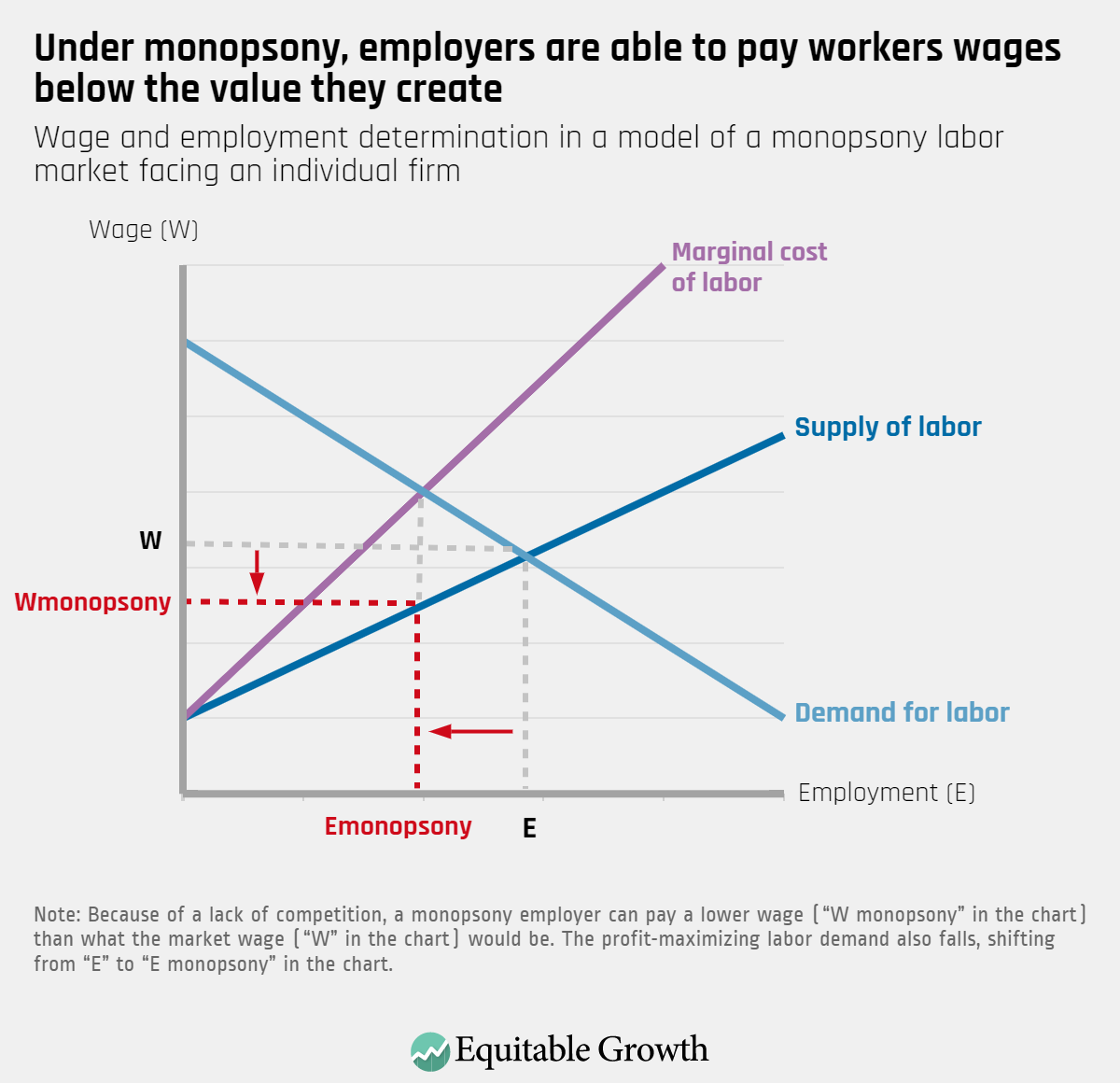

Consider the basic supply-and-demand model of the labor market. According to this framework, when governments enact a wage floor, they artificially set wages at a level that reduces firms' desire to hire workers. As demand moves away from equilibrium and up along the labor demand curve, people who would be willing to sell their labor at a "competitive" wage (the theoretical market rate) are unable to find work. In this hypothetical labor market, then, firms hire fewer workers than they want to, workers who would like to sell their labor cannot, and employment is lower than it would be under equilibrium. In economic terms, wage floors lead to socially inefficient outcomes. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Further, under this model of perfect competition, employers are "price-takers," meaning that they must accept the market wage and have no way of influencing it. The assumptions that underpin the perfectly competitive model of the labor market—for instance, that all market participants have perfect information, that all workers are able to seamlessly transition from job to job, and that wages are an accurate reflection of all workers' productivity—also imply that workers are very sensitive to wages. In other words, an employer only needs to pay one cent more than its competitors to have an unlimited supply of workers.

At last month's event, Bahn noted, however, that "if workers face frictions when trying to find a job—if workers do not know what jobs are available or face constraints in what kind of position they can take—then employers do not need to only pay one cent more than their competitors to have an unlimited flow of workers."

Indeed, researchers document that various obstacles when trying to land a position, the concentration of a few employers in any given labor market, and employee preferences about job characteristics besides wages make workers much less sensitive to pay than the perfectly competitive model proposes. "In the actual labor market, employers do not have to offer pay raises or cost of living adjustments tied to inflation if they do not have to compete for workers," Bahn told congressional staff.

In addition, empirical evidence shows that these noncompetitive forces affect U.S. labor market dynamics, with monopsony power giving employers the ability to pay wages below workers' productivity. For instance, a team of economists at the University of California, Los Angeles, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Burning Glass Technologies shows that more than 10 percent of the country's workforce is in labor markets where lack of outside options for their current jobs leads to employer concentration, depressing these workers' wages by at least 2 percent.

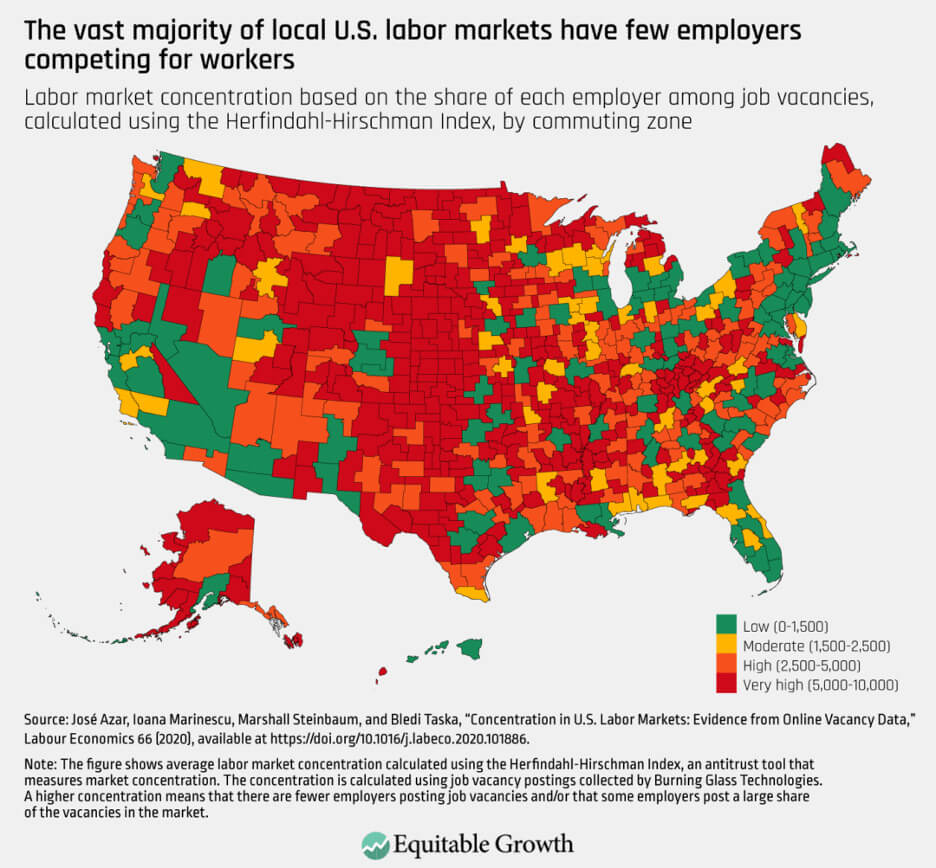

In other words, in parts of the country where relatively few employers are competing to hire, lack of competition pushes down average pay. Highly concentrated labor markets, another study finds, are especially pervasive in rural and less densely populated areas. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Other studies highlight how one big employer can influence marketwide wages. For instance, research by economist Ellora Derenoncourt (now at Princeton University) and Clemens Noelke and David Weil at Brandeis University shows that as Amazon.com Inc. set a $15 minimum wage in late 2018, other employers in the same commuting zone had to increase wages. Amazon and other big and powerful employers, the authors find, can therefore act as a wage-setters rather than price-takers, pushing wages up or dragging them down depending on what their particular corporate policy is at a given time.

A study examining how the opening of Walmart Supercenters affects local labor markets captures how one firm's monopsony power leads to worse labor market outcomes. The research finds that Supercenters lead to a decline in countywide employment and earnings as Walmart undercuts wages through low-road employment practices that spill over on other local workers and industries—a dynamic that was mitigated in the counties that experienced an increase in the minimum wage and that would not take place under perfect competition.

So, how does our model of the labor market change when we assume imperfect competition? Under monopsony, the labor demand curve and labor supply curve intersect at both a lower wage and at a lower employment level than would be achieved under equilibrium. This results in socially inefficient outcomes, where the lost wages due to underpayment are kept as firms' profits, with workers making less than the value they contribute. Contrary to the perfectly competitive model of the labor market, in this model, higher wages also lead to greater equilibrium employment. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

In contrast to Figure 3 above, in a competitive labor market, if a firm tried to pay only "W monopsony" wages, then workers would go to other firms willing to pay a higher wage.

How policymakers can protect workers from monopsony power in the U.S. labor market

There are two broad areas of public policies that can counteract these forces and create greater balance between the power of employers and the power of workers: pro-competition policies and pro-worker policies.

To boost competition in labor markets, policymakers can start by banning noncompete agreements—contracts that limit workers' ability to move from job to job and that affect a large share of low-wage workers. Public policy also should support workers' bargaining power by raising the federal minimum wage, expanding the right to organize and join a labor union, and enforcing labor standards to prevent violations, such as wage theft and employment discrimination.

Together, these policies will boost wages and increase job quality, increase competition and productivity, and drive broad-based economic growth.

To learn more about how monopsony affects the U.S. labor market, see the presentation slides from the March 23 congressional briefing here. For a write-up of a previous "Econ 101" briefing, on the effects of federal tax changes, see here.

The post Understanding the economics of monopsony: How labor markets work under imperfect competition appeared first on Equitable Growth.