https://www.epi.org/blog/ui-claims-rising-as-jobs-remain-scarce-senate-republicans-must-stop-blocking-the-restoration-of-ui-benefits/

Last week, total initial unemployment insurance (UI) claims rose for the fourth straight week, from 1.6 million to 1.7 million. Of last week's 1.7 million, 884,000 applied for regular state UI and 839,000 applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). A reminder: Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) is the federal program for workers who are not eligible for regular unemployment insurance, like gig workers. It provides up to 39 weeks of benefits and expires at the end of this year.

Last week was the 25th week in a row total initial claims were far greater than the worst week of the Great Recession. If you restrict to regular state claims (because we didn't have PUA in the Great Recession), claims are still greater than the 2nd-worst week of the Great Recession. (Remember when looking back farther than two weeks, you must compare not-seasonally-adjusted data, because DOL changed—improved—the way they do seasonal adjustments starting with last week's release, but they unfortunately didn't correct the earlier data.)

Most states provide 26 weeks of regular state benefits. After an individual exhausts those benefits, they can move onto Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC), which is an additional 13 weeks of state UI benefits that is available only to people who were on regular state UI. Given that continuing claims for regular state benefits have been elevated since the third week in March, we should begin to see PEUC spike up dramatically soon (starting around the week ending September 19th—however, because of reporting delays for PEUC, we won't actually get PEUC data from September 19th until October 8th). It is also important to remember that people haven't just lost their jobs. An estimated 12 millionworkers and their family members have lost employer-provided health insurance due to COVID-19.

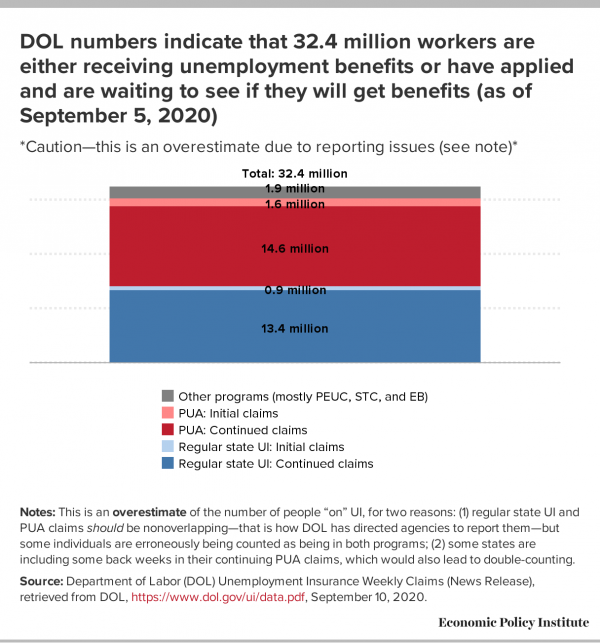

Figure A combines the most recent data on both continuing claims and initial claims to get a measure of the total number of people "on" unemployment benefits as of September 5th. DOL numbers indicate that right now, 32.4 million workers are either on unemployment benefits, have been approved and are waiting for benefits, or have applied recently and are waiting to get approved. But importantly, Figure A is an overestimate of the number of people "on" UI, for two reasons: (1) Some individuals are being counted twice. Regular state UI and PUA claims shouldbe non-overlapping—that is how DOL has directed state agencies to report them—but some individuals are erroneously being counted as being in both programs; (2) Some states are including some back weeks in their continuing PUA claims, which would also lead to double counting (the discussion around Figure 3 in this papercovers this issue well).

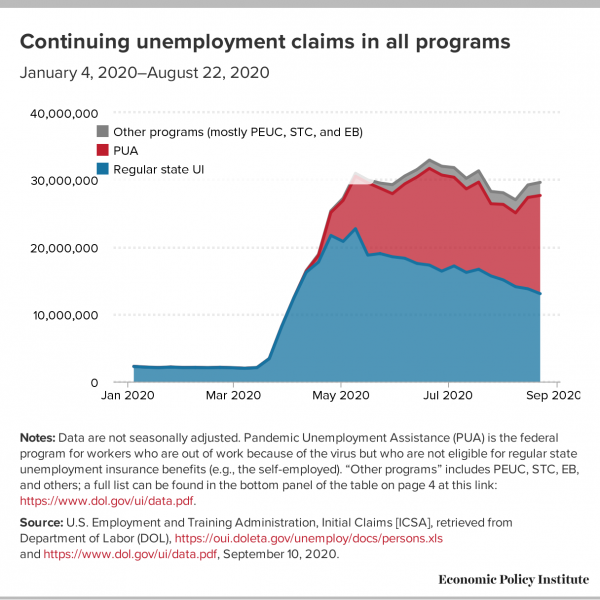

Figure B shows continuing claims in all programs over time (the latest data are for August 22). Continuing claims are more than 28 million above where they were a year ago. However, the above caveat about potential double counting applies here too, which means the trends over time should be interpreted with caution.

I have received many questions about how to square the UI numbers with the monthly jobs numbers. This thread from Jobs Day last Friday explains it (in particular, tweets six–eight show how the number of officially unemployed is "undercounted," and tweets 20–24 show how UI claims are overcounted).

Republicans in the Senate allowed the across-the-board $600 increase in weekly UI benefits to expire at the end of July. Last week was the sixth week of unemployment in this pandemic for which recipients did not get the extra $600. That means most people on UI are now are forced to get by on the meager benefits that are in place without the extra payment, benefits which are typically around 40% of their pre-virus earnings. It goes without saying that most folks can't exist on 40% of prior earnings without experiencing a sharp drop in living standards and enormous pain.

In early August, President Trump issued a mockery of an executive memorandum. It was supposed to give recipients an additional $300 or $400 in benefits per week. But in reality, even this drastically reduced benefit will be extremely delayed for most workers, is only available for a few weeks, and is not available at all for many. This chart from The Century Foundation shows how much less in benefits people are getting under Trump's executive memorandum than they did under the CARES Act. The executive memorandum's main impact was to divert attention from the desperate need for the real relief that can only come through legislation. Congress must act, but Republicans in the Senate are blocking progress.

Blocking the $600 is terrible on both humanitarian and economic grounds. The extra $600 was supporting a huge amount of spending by people who now have to make drastic cuts. The spending made possible by the $600 was supporting 5.1 million jobs. Cutting that $600 means cutting those jobs—it means the workers who were providing the goods and services that UI recipients were spending that $600 on lose their jobs. The map in Figure B of this blog post shows many jobs will be lost by state now that the $600 unemployment benefit has been allowed to expire. The labor market is still 11.5 million jobs below where we were before the virus hit. Now is not the time to cut benefits that support jobs.

But what about the supposed work disincentive effect of the $600? Rigorous empirical studies show that any theoretical work disincentive effect of the $600 was so minor that it cannot even be detected. For example, a study by Yale economistsfound no evidence that recipients of more generous benefits were less likely to return to work, which is what we would expect to see if the extra payments really were a disincentive to work. And a case in point: in May/June/July—with the $600 in place—9.2 million people went back to work, and a large share of likely UI recipients who returned to work were making more on UI than their prior wage. The extra benefits did not stop them from going back. A job offer is too important at a time like this to be traded for a temporary increase in benefits, and when commentators ignore that, they are ignoring the realities of the lives of working people. Further, there are 8.5 million more unemployed workers than job openings, meaning millions will remain jobless no matter what they do. Dropping the $600 cannot incentivize people to get jobs that are not there. And, as Figure B shows, total continued claims in the most recent data are higher than they were when the $600 expired. It simply wasn't the $600 that was keeping people on UI, it was the fact that they can't find work.

Dropping the $600 is also exacerbating racial inequality. Due to the impact of historic and current systemic racism, Black and brown communities have seen more job loss in this recession, and have less wealth to fall back on. They are taking a much bigger hit with the expiration of the $600. This is particularly true for Black and brown women and their families, because in this recession, these women have seen the largest job losses of all. The Senate must extend the UI provisions of the CARES Act, both to provide relief to the jobless and to the bolster the broader economy.

-- via my feedly newsfeed